Charles Ponzi. Bernie Madoff. Billy “Fyre Festival” McFarland. History is littered with the misdeeds of conmen who pulled the wool over the public’s eyes and made a killing. Some, like Frank Abagnale – the model for Leonardo Dicaprio’s character in Catch Me if You Can – pulled off cons so big they’ve become legendary. But not even Abagnale could compete with our subject today. Gregor MacGregor was many things: soldier, pirate, pathological liar. He was also the man who pulled off the biggest con in history.

In 1821, MacGregor arrived in London with tall tales of a new Latin American nation where fortunes could be made. Using his deadly charm, MacGregor managed to not only swindle banks, investors, and ordinary people out of the 19th Century equivalent of billions of pounds, he indulged in fabrications on such a colossal scale that even Europe’s governments were fooled. But how did this Scottish nobody create a con so big it swallowed an entire continent? Join us as we explore the life of Gregor MacGregor, the most amoral adventurer to ever live.

Birth of a Con Man

When he came to tell the story of his birth many years later, Gregor MacGregor would never let two details remain the same. He was born into high Scottish nobility. He was descended from the legendary outlaw Rob Roy. His ancestors were adventurers who founded Scotland’s doomed colony in the Darien Gap.

The odd thing was, he needn’t have bothered.

Gregor MacGregor’s background was interesting enough even without his tall tales.

Born on Christmas Eve, 1786, MacGregor came from, well, the MacGregors, a Jacobite Clan that had only just been relegalized after 100 years as outlaws. While his dad wasn’t the chief, as MacGregor would claim, his family was still notable. His grandpa had been an officer in what would become the Black Watch. His father was a ship captain.

In short, young MacGregor had action in his blood. And in 1803, when MacGregor was only 16, that blood would drive him to seek adventure in the British Army. As luck would have it, 1803 was the year the Napoleonic Wars broke out, and MacGregor was hurriedly posted to the island of Guernsey to defend against French invasion. But that invasion never came. Instead, MacGregor wound up living a deeply unadventurous life of waiting around.

Not that his time on Guernsey was all a waste. It was while on assignment that MacGregor met his first wife. Maria Bowater was the sort of catch young enlisted men used to dream about. Her father was an admiral, her family members were MPs. Oh, and they were absolutely, stinking rich.

In no time at all, MacGregor had charmed his way into marrying her, much to the horror of her family.

No sooner than they tied the knot MacGregor was using his wife’s money to buy himself the rank of captain and get transferred down to Gibraltar.

But while the weather may have been nicer on Spain’s southern tip, life was still boring. For the next four years, MacGregor did nothing but stand around, waiting for a French fleet that never came. Then, in 1809, just as MacGregor was planning to give up and return to Scotland, excitement finally arrived.

The year before, Napoleon had invaded Spain, engulfing the whole of Iberia in the Peninsular War. Sensing a chance to give Napoleon a black eye, the British decided to intervene. And that’s how Gregor MacGregor found himself in Portugal fighting Napoleon’s forces. Yet even in the heat of combat, MacGregor couldn’t settle. In October, he sold his rank of captain and departed the British Army for the Portuguese one. But by May 1810, he’d also got bored of the Portuguese and resigned again.

Come summer, 1810, MacGregor was back in Scotland, feeling as unfulfilled as ever. But he was no longer merely “Gregor MacGregor.” On leaving the Portuguese Army, MacGregor had started telling people he’d been knighted for his service, and was now “Sir MacGregor”. It was a stupid lie. A dumb, egotistical little lie that shouldn’t have changed anything. Yet change things it did. When people didn’t question it, MacGregor realized just how easy lying about even huge things really was. It was a revelation that would soon take the young man to some very bizarre places.

Life with the Liberator

In April 1812, a ship pulled into port near Caracas, Venezuela, and disgorged a slender Scot in his mid-twenties. It had been two years since MacGregor had left Portugal disillusioned, and much had happened.

In 1811, his wife had died, and his in-laws had cut him off financially. MacGregor had left Britain, in search of something – anything – that would keep his mind occupied.

Luckily, 1811 wasn’t short of opportunities for a would-be adventurer. That year, Venezuela had declared independence from Spain, kickstarting the South American Wars of Independence. MacGregor had decided to get involved. No sooner than he had landed, the then-Republican leader, Francisco de Miranda, appointed him a cavalry officer. But it’d be an even bigger name in Caracas society that MacGregor would soon get involved with, thanks to his 1812 marriage to Josefa Antonia Andrea Aristiguieta y Llovera.

Josefa, you see, was cousin to none other than Simon Bolivar. Not that his newfound connection would immediately work out well for MacGregor. Just months after his marriage, MacGregor was in flight, running for safety as the First Venezuelan Republic fell to Spanish forces. Francisco de Miranda was captured, while both MacGregor and Bolivar only escaped – heading in opposite directions – by the skin of their teeth.

And so began the period of Gregor MacGregor’s life where he kept crossing paths with the greatest figure in Latin American history, only for it all to keep going horribly pear-shaped. In 1813, for example, MacGregor volunteered in the New Granada army, only to be assigned to a remote border town and miss Bolivar’s Admirable Campaign and founding of the Second Venezuelan Republic. In 1814, the two both wound up in Cartagena after the Second Republic fell, but Bolivar was forced into exile while MacGregor got trapped in the siege of the city. Finally, MacGregor reconnected with Bolivar in Haiti in early 1816 and joined his latest campaign. It was a campaign that would nearly cost MacGregor his life.

By now, most of Venezuela was back under Royalist control. Bolivar’s plan was to land men at strategic points along the coast, then coordinate a mass uprising. Put in charge of 600 troops, MacGregor was quietly dropped at Ocumare. Unfortunately, the plan instantly fell apart, Bolivar was forced into retreat, and MacGregor and his men were left standing on the shore, their mouths dangling open as their ride disappeared.

They were trapped in Royalist territory, over 300km from the nearest Republican stronghold.

They had no boats, limited ammunition, even-more limited provisions, and were surrounded by swampland. At that moment, it must’ve seemed to the 600 men like death was a certainty. They hadn’t counted on MacGregor’s talent for self-preservation. In a remarkable feat of leadership, MacGregor led his men on a march right through Royalist territory, executing innumerable brilliant maneuvers to keep the enemy at bay. He tricked the Spanish troops into walking into swamps. He had his men charge blockades on foot and punch right through.

It was like watching LeBron James lead Elmer Fudd around a basketball court, with the dimwitted Royalists fumbling every play while MacGregor ran circles around them, laughing. And yes, as far as we know, we are the only biographical site delivering history via Space Jam 2 analogies. You’re welcome.

After weeks of running battles, MacGregor finally led his men into the safety of a Republican town.

When news leaked of his 300km trek, the Republican camps exploded. MacGregor became a hero overnight, his name celebrated across the continent. Suddenly, everyone wanted to serve under him, the guy who’d married into Bolivar’s family, and then out-Bolivared Bolivar. But, sadly, this isn’t an article about Gregor MacGregor, revolutionary general. It’s a video about Gregor MacGregor, con man extraordinaire. Those soldiers all clamoring to serve under him didn’t know it yet, but MacGregor would soon lead countless of their number into early graves.

Third Time’s the Charm

In the wake of MacGregor’s daring escape from Ocumare, Bolivar personally awarded him the Order of Libertadores – hopefully while shuffling awkwardly and mumbling “sorry I abandoned you back there, bro.”

But MacGregor was disappointed. He hadn’t gone through hell just to get a shiny new medal.

No, he wanted a promotion, a raise, something to show the world he was a hero. If Ocumare wasn’t enough for his cousin-in-law, MacGregor would just have to go one bigger.

That fall, mercenaries up in Pittsburgh began to whisper about a Scottish man doing the rounds, hiring people for a private invasion of Spanish Florida. The Scot was a Portuguese knight, a Venezuelan hero. More to the point, he was very generous. Anyone who joined him was being given titles to huge estates in Florida.

For the rough and tumble men of Pittsburgh’s dive bars, it seemed like a no-brainer.

This is how in June 1817, MacGregor was able to sail for Amelia Island, Florida at the head of 200 mercenaries. There was just one minor catch. MacGregor didn’t actually own the land he’d been dishing out to his private army. But, hey, while spoil a good invasion, right? Not when everything was going so well.

And it really was. When the only Spanish garrison on the island saw all these armed Americans, they assumed it was the head of a full-blown US force and surrendered. Now all MacGregor needed to do was press his advantage, take a few more forts, and he’d soon have another victory to rival Ocumare.

But that didn’t happen.

Instead, MacGregor declared Amelia Island the Republic of East Florida, and then simply settled in to enjoy getting drunk and sunning himself. For MacGregor’s men, this must’ve been a “what the-?” moment. Then MacGregor started paying them in Republic of East Florida dollars he’d made himself and it became a “Whaaa-?!” Finally, one morning in September, the mercenaries awoke to find MacGregor had taken the ship and remaining money and simply sailed away, leaving them to their fates. At that point, they probably couldn’t even summon a squeak of surprise to show how they felt.

Following the Florida failure, MacGregor badly fell out of favor with Bolivar. So he tried again. In 1818, MacGregor sailed back to Britain, hired 500 more men, and this time tried to conquer Panama. Landing a force of 200 at Porto Bello, he took the city…

…and then went straight back to lounging around in the sun, drinking rum and failing to do anything that might stave off a potential Spanish counterattack. This last bit proved important when the potential counterattack became an actual counterattack and MacGregor was forced to flee, once again leaving his mercenaries to their fates. By now, the Scot was starting to look less like the capable general of Ocumare, and more like a shallow egotist who’d just happened to get lucky. But his name still carried enough shine for MacGregor’s surviving men to follow him on one last invasion.

In October, 1819, MacGregor landed outside a Royalist holdout on Venezuela’s coast. It was the exact same checklist as Amelia Island and Porto Bello: MacGregor takes city? Check. MacGregor gets drunk rather than organize defenses? Check. When things go south MacGregor sails away and leaves his men to their fates? Double check. This time, those fates were particularly gruesome. After the Spanish retook the city, they lined up all of MacGregor’s surviving mercenaries and had them shot

In the aftermath of MacGregor’s third colossal screw up, Simon Bolivar didn’t so much throw the book at him as crush him beneath an entire library of disapproval.

Bolivar declared his cousin-in-law a traitor. He issued a decree that any Venezuelan who saw MacGregor should kill him on sight. But while this was the end of MacGregor’s time as a revolutionary warrior, it wasn’t the end of the man himself. When he resurfaced, it was going to be with a con that would go down in history.

The Con is On

Sprawling along the Caribbean coasts of modern-day Nicaragua and Honduras, the Mosquito Shore is exactly as unappetizing as its name suggests. It’s a hot, wet, desolate place where life is cheap, disease is rife, and mosquitoes omnipresent. In April, 1820, Gregor MacGregor hopped off a boat and vanished into the mangrove forests of this tropical Hell, desperate to lose himself. By now, it wasn’t just Bolivar who wanted him dead.

The Spanish, the Americans, the British… all, for varying reasons, had MacGregor’s name on a hit list. In the movie of MacGregor’s life, this would be the low-point, the part where all seems lost. But you know what always comes after the low point in any movie script? The part where the hero triumphs. While hiding on the Mosquito Shore, MacGregor came into contact with one of the local tribal leaders, a guy who styled himself King George Frederick Augustus. Being a natural charmer, MacGregor got the guy drunk and spent a few days partying with him. By the time he emerged from the king’s hut, weary and hungover, MacGregor was clutching a title deed to 8 million acres of tribal land. This piece of paper would become the basis for his audacious next move.

Back in MacGregor’s native Britain, the nation was gearing up for the coronation of George IV. There were street parties and dignitaries came from all over the world. In fact, there were so many dignitaries no-one noticed when one arrived from a country that didn’t exist.

His Serene Highness Gregor MacGregor the First, Sovereign Prince of the State of Poyais and its Dependencies, and Cacique of the Poyer Nation arrived in London in summer, 1821. Just like with MacGregor’s fake knighthood in 1810, no-one questioned his absurd new title. To understand why, you have to remember when this story is set. In 1821, a whole bunch of new nations had just exploded into existence: Mexico, Gran Colombia, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Peru. For Londoners, it wasn’t much of a stretch to believe Poyais might be among them. Especially when the Poyais envoy was related by marriage to Simon freaking-Bolivar. But MacGregor did more than just trade on his connections to fool people.

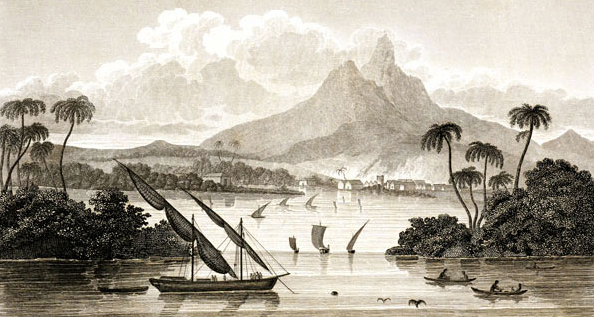

Under the pseudonym Thomas Strangeways, he published a guidebook to Poyais, detailing the nation’s government, its geography, its climate, its architecture. This was serious imagination, something Tolkein would’ve been proud to write, and it was shot through with glimpses of a utopia. There was the soil, so fertile it could support three harvests a year. There were the riverbeds, where lumps of gold lay along the banks. And there was the fact that, uniquely for Central America, Poyais had no tropical diseases. Trust us, that last one will soon seem bitterly ironic.

But why did MacGregor go to all this trouble to invent a fake country? For an answer to that, you need to look to London’s Scottish communities. That same summer, the Poyais envoy began visiting them. He was offering them an opportunity, he said. An opportunity not just to better their own lives by moving to Poyais, but an opportunity to establish Scotland’s first viable colony. A chance to make their country into a global player. All they had to do, Gregor MacGregor told his fellow Scots, was to buy one of these plots of Poyais land he was selling. Fertile land that would set them for life. Faced with such an offer, who could refuse?

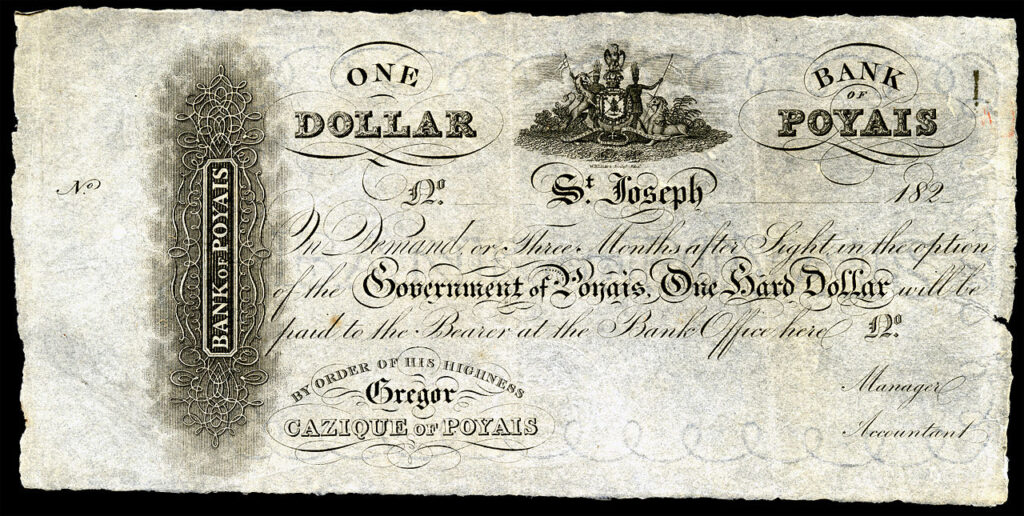

The Bubble

By the fall of 1822, interest in Poyais was running rampant. The first boatload of Scottish settlers had just departed for the country, and a general bubble in Latin American securities was expanding. So when MacGregor asked a bank to underwrite Poyais bonds, they simply nodded and handed him £200,000. Using that money, MacGregor opened Poyais consulates across Britain, adding to the scheme’s veneer of legitimacy. For MacGregor, these were the salad days; a phrase which means the heyday of something, which is an odd choice when you consider how boring salad is. By winter, investment in Poyais bonds had generated over a billion U.S. dollars in today’s money. And MacGregor was still selling land to gullible Scots!

The second boat of settlers departed in January, 1823. But there’s one problem with dispatching boatloads of settlers to a non-existent country. What do you do when they finally arrive? Well, let’s find out. In November, 1822, the first ship reached the Mosquito Shore. As the boat approached land, the Scottish settlers all donned their fanciest outfits and fired the gun so a Poyais boat would come out and guide them to the capital. Instead, the gunshot echoed across the empty waters and mangrove swamps, answered only by deafening silence.

At first, the settlers assumed they must’ve made a navigation error. So they all had their stuff unloaded onto a deserted stretch of coast, and sent the captain off to find Poyais. It’s worth noting that these were not young, hardy types desperate for adventure. Most of those caught up in the Poyais scheme were older folks looking for an easy retirement, or families with young children. Surviving on a deserted stretch of tropical shore was definitely not within their skillset.

In March, 1823, the second ship joined the stranded settlers. Incredibly, everyone still assumed their navigation was off. Even when the captain of the first ship returned and said “so, I’ve sailed all up and down this coast and there’s no Poyais,” they told him, “err, obviously there is. Duh. Try again.” So off the captain went again. And the now hundreds-strong crowd of settlers settled down to wait again. That same month, a hurricane battered the Mosquito Shore, destroying supplies, and wrecking the remaining ship. Then the rains came; thick, heavy, endless rains that left the settlers soaked.

Finally, in the wake of the rains, came the mosquitoes. If you’ve ever been to the tropics in rainy season, you’ll have seen just how thick the air can get with mosquitoes carrying yellow fever and malaria. On the deserted shore, the insects mobbed the unprepared settlers, biting them, infecting them. One by one, the abandoned Scots began to die. Babies passed away in their mothers’ arms. Elderly women died, wracked with malaria. Of the 200 or so Poyais settlers who reached the Mosquito Shore, it’s estimated over two-thirds were killed by tropical diseases. It was a massacre by neglect. A death sentence as sure as a firing squad.

The only reason anyone survived is because a ship from British Honduras just happened to pass and alert the colonial authorities. For the rest of 1823, the Royal Navy was overwhelmed evacuating the survivors and intercepting ships headed for Poyais. By the year’s end, they’d stopped five more settler ships, each carrying hundreds of people. Had they reached the Mosquito Shore, it’s likely the death toll of the Poyais scheme would’ve topped a thousand.

Back in London, news of the disaster first broke in October, 1823. Immediately, lots of very angry people began looking for Poyais’ charming envoy. But they were too late. MacGregor had fled England just before the story arrived, taking as much of his ill-gotten cash as he could carry. It was a horrific denouement to the wildest con ever pulled. Unbelievably, it still wasn’t over. Gregor MacGregor wouldn’t be done with the Poyais scheme for another fifteen years.

No Bad Deed Goes Unrewarded

From 1823 to 1838, MacGregor pulled his Poyais con again and again. Incredibly, he never faced any serious punishment for it. Even after the harrowing tale of the survivors got out, no one in Europe could accept Poyais didn’t exist. MacGregor had simply lied too big. In the same way our brains wouldn’t be able to process the revelation that, say, Hawaii wasn’t real, people in the 1820s just couldn’t comprehend the idea that Poyais was fictional.

When MacGregor settled in Paris, the French government even made him an advisor on Latin American affairs! This despite MacGregor restarting his fake bonds scheme in France. Although the scheme itself was busted in 1825, MacGregor successfully blamed his French partners and again got away Scot free. He even returned to London and got more bonds underwritten for £800,000. While no investors bit this time, it wasn’t because of the tragedy on the Mosquito Shore. It was because the Latin American securities bubble had just burst, and no-one wanted to risk another.

For the next few years, MacGregor hawked his scheme up and down Britain. While he never again hit the big time, he always had just enough money coming in to keep the fiction going, to keep people believing in Poyais. Finally, in 1838, MacGregor’s wife Josefa died. Suddenly alone in gloomy Britain, the con man seems to have at last given up on his con. That October, MacGregor got on a boat and sailed back to Caracas. He never mentioned Poyais again.

So… this is the moment, right? The moment when MacGregor finally gets his comeuppance. I mean, he’s headed back to Venezuela, the very place Simon Bolivar left orders that he be killed on sight. If you’re hoping for a moral end to this story, best switch off now and construct one in your own head.

See, Bolivar had died all the way back in 1830, by which time he became incredibly unpopular. With Bolivar’s name now mud, everyone was like “I mean, do we really need to kill this random Scottish dude?”

So they let MacGregor land. They even let him request an audience with the government. At which point, Lady Luck dropped an utterly undeserved gold nugget right into MacGregor’s lap.

Remember Ocumare, the one time that MacGregor actually acted like a hero? Well, General Carlos Soublette did. He’d been under MacGregor’s command during that mission and seen the con man at his best. Since he’d never followed MacGregor to Florida, or Porto Bello, or even heard of Poyais, he had no idea of MacGregor’s true character. And now Soublette was a member of Venezuela’s government. When he saw MacGregor, he basically let out a cry and threw his arms around him. That was how, in 1838, Venezuela came to reinstate Gregor MacGregor’s rank in its army, hand over twenty-five years’ back pay, and give him a generous pension.

For the next seven years, MacGregor lived in Caracas, wealthy, happy, and respected by all. He finally died a peaceful death on December 4, 1845, without having ever repented of his cons. Sometimes, life really is unfair. Today, it’s estimated that, between the Poyais scheme and all those times he abandoned his men, Gregor MacGregor was responsible for the deaths of 500 people. Yet even though he never got his comeuppance, his story offers us all excellent moral lessons.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming that the world is fair. That maybe bad things sometimes happen, but – in the end – everything will always balance out. The tale of Gregor MacGregor laughs in the face of this. Here was a man who treated other people as disposable trash, only there to fuel his own fantasies. A man who sacrificed literally hundreds of lives to the God of his ego. And he never tasted justice for even a single second.

Unique among figures we’ve covered, MacGregor offers us a bleak but necessary warning. Sometimes, good doesn’t triumph. Sometimes, the happy, wealthy, respected people are the ones who have caused untold suffering. Gregor MacGregor may be long dead, but there will always be others out there like him, charming and amoral. If his life shows us anything, it’s that we should always be on the lookout for these people. Even when they seem to be the most respectable types you could ever hope to meet.

Sources

Excellent podcast on Gregor MacGregor’s life: https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2016/10/517a-supplemental-gregor-macgregor.html

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s entry (paywall, but free to access for UK residents with library cards): https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-17519

Good overview of his cons: https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/gregor-macgregor-prince-poyais

BBC’s take on it all: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160127-the-conman-who-pulled-off-historys-most-audacious-scam

Biographics on Simon Bolivar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1bmJGX0md8