It was the shot heard around the world. On June 28, 1914, on a sweltering street in Sarajevo, a gunman fired into an open-topped car, killing Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The murder of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire was the push that set the dominoes of Europe falling. One by one, the great nations declared war, until countries as far away as India, Japan, and America had all been sucked into the quagmire. Known as WWI, that quagmire would kill twenty million people and change the course of history.

But who was Franz Ferdinand? Who was this obscure archduke whose death set the world ablaze?

Born into a branch of the Austrian royal family, Franz Ferdinand seemed destined for a life of rich obscurity. Until, one day, tragic events conspired to make him heir to his family’s empire. As emperor-in-waiting, Ferdinand implemented reforms and worked on plans that could’ve changed everything… only for an assassin’s bullet to cut him down too soon. In today’s Biographics, we’re investigating the life of the man whose death started WWI… and considering what might have happened had he lived.

The Two Heirs

At the moment Franz Ferdinad first opened his eyes, on 18 December 1863, not even the greatest seer could’ve predicted the tortured route that would lead to him dying on an anonymous Sarajevo street half a century later.

At the time, Sarajevo was within the orbit of the decaying Ottoman Empire. Franz Ferdinand, meanwhile, had been born into the chilly air of the Ottomans’ ancient enemy: Austria. Not that being enemies meant the empires were at war. In fact, they were in a period of relative peace that had allowed Ferdinand’s ostensibly-military family to become lazy and boring.

Ferdinand’s father, Archduke Karl Ludwig, was as staid and conservative as a church belltower. His mother, Maria Annunziata, was a Bourbon princess who’d done nothing of note. Yet, for all their dull respectability, the family did have one claim on being interesting.

Karl Ludwig was the brother was Franz Josef, the Habsburg emperor of Austria.

Not that baby Franz Ferdinand got much out of his famous uncle. Since Franz Josef already had a son – Rudolf – there was little chance young Ferdinand would ever become emperor himself.

Obviously, it wasn’t impossible. He was third in line.

But it was unlikely enough that Ferdinand was kept away from the corridors of power, even as he had to go through the standard Habsburg upbringing of God, army, and duty.

In fact, Franz Ferdinand’s upbringing was so utterly average that there’s very little to say about it. Perhaps the only way the boy diverged from the standard Habsburg mold was in his passion for botany. While other Habsburg men valued their guns and uniforms, Franz Ferdinand found an unlikely outlet in flowers.

From early childhood, it’s said that he never looked quite as content as when he was gently pressing a rose between the pages of a book.

Still, it’s not like Ferdinand’s horticultural side was a sign of an artistic spirit.

He really did value guns and uniforms and enjoyed his conservative upbringing. The same cannot be said for Rudolf. The only son of emperor Franz Josef, Crown Prince Rudolf had been born on August 21, 1858, ending a run of unwanted baby girls.

For Franz Josef, the arrival of a viable heir had been such a cause for celebration that he’d made Rudolf commander of an entire infantry regiment the very next day.

No word on how the previous commander felt about being replaced by a literally newborn baby. But while his cousin Franz Ferdinand would enjoy his military upbringing, Rudolf had hated it from the get-go.

From a young age, Rudolf had been pushed off onto a sadistic tutor named Major-General Count Leopold Gondrecourt.

Gondrecourt was that asshole Phys Ed teacher you had as a kid, pumped up on 19th Century notions of manliness, and given carte blanche to do whatever he liked to Rudolf. The Crown Prince was made to exercise outdoors for hours in the depths of the Austrian winter. Guns were fired near his head in the middle of the night to wake him up.

By 1865, Rudolf was a mental wreck. But still, Franz Josef refused to fire Gondrecourt, believing Rudolf was a weakling who needed toughening up. Finally, Empress Sisi intervened, threatening to leave the royal household if Gondrecourt kept abusing their son.

But by then, the damage had already been done.

Always a sensitive boy, Rudolf would never recover from the hard years he spent in the hands of Count Gondrecourt. It was these mental scars that would soon entwine his fate with Franz Ferdinand’s.

Turning Points

By the early 1880s, the two cousins had grown into very different people.

Off on his family’s estates, Franz Ferdinand had become exactly the sort of man the newly-reorganized Austro-Hungarian Empire was designed to churn out.

He’d joined the army, become a captain within a year.

Now he was in his early twenties and climbing the ranks, ready to serve his country. Even his love of flowers had been offset by a newfound passion for the masculine sport of hunting. And no one hunted quite like Franz Ferdinand.

If it moved and wasn’t wearing an Austrian army uniform then Ferdinand was more than happy to shoot it. It’s estimated he shot over a quarter of a million animals in his lifetime. But, despite the outward success of Ferdinand’s military upbringing, it hadn’t sanded off all the rough edges.

Adult Franz Ferdinand was a man with a volcanic temper.

Like many rich people, he was used to getting what he wanted. But whereas most rich people sulk in private when they don’t, Ferdinand sulked openly, for days on end.

It got so bad that his army buddies would avoid him like most of us would avoid a pedophile made of ebola.

Still, at least Franz Ferdiand was broadly content. The same can’t be said for Rudolf. In the years since Count Gondrecourt had been kicked out on his sadistic backside, Ferdinand’s cousin had gone from bad to worse. He’d become melancholic. Alcoholic. Other “cholics” that medical science hasn’t even dreamed of. Yet even as he emotionally decayed, Rudolf intellectually sharpened.

At the time of our story, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was home to a kaleidoscope of ethnicities. There were Czechs. Slovaks. Poles. Italians. Croats. Slovenes. Serbs. Romanians. Ukrainians. However, only Austrians and Hungarians were represented at the top. While that had been common in empires of the past, it wasn’t so viable in a Europe now brimming with nationalism.

As future emperor, Rudolf was desperate to reform things.

Unfortunately, his father’s motto was essentially “do nothing and hope for the best.” Franz Josef was slow. Conservative. As suspicious of demands for autonomy as he was of his heir’s reforming zeal.

But rather than talk about it, Franz Josef simply sidelined Rudolf, marrying him off to Princess Sophie of Belgium, a woman so dull she could’ve been used as an anesthetic. Frustrated at court, stuck with a wife he hated, and still dealing with the scars of his abusive childhood, Rudolf began to drift into a poisonous depression.

Interestingly, it was around this time that Franz Ferdiand’s life also took a grim turn. In the mid-1880s, the third in line to the throne was diagnosed with tuberculosis – a lung disease that killed many in the 19th Century.

But things were worse for Rudolf.

While Franz Ferdinand’s disease was something that could be understood, Rudolf’s disease was something that hid away from sight, something his family didn’t even try to understand. It was an attitude that would lead to tragedy.

On January 30, 1889, Rudolf – now extremely depressed – took his 17-year old lover, Baroness Mary Vetsera, to his hunting lodge Mayerling. There, the two signed a suicide pact. Then Rudolf shot her through the head before turning his pistol on himself.

The bullet that passed through Rudolf’s brain did more than just kill the Crown Prince. It ended Franz Josef’s line, extinguishing his only male heir. It was a moment when history trembled, then pivoted on its axis. When the multiverse branched.

Poor Franz Ferdinand didn’t know it yet, but Rudolf’s two gunshots had just set him on a path to his own, equally-violent destiny.

The Heir is Dead… Long Live the Heir!

Of all the unintended consequences of Rudolf’s suicide, Franz Ferdinand becoming heir was likely the most unintended of all. That’s because Ferdinand was third in line to the throne. After Rudolf decided to decorate Mayerling’s walls with the inside of his skull, the succession passed to Ferdinand’s dad, Karl Ludwig.

But Karl wasn’t interested. Within days, he’d abdicated his claim.

And just like that, Franz Ferdinand – hot-headed, military, flower-loving Franz Ferdinand – was the future emperor. For Emperor Franz Josef, this was a little like being forced to swallow a pint of freshly-squeezed disappointment.

Franzes Ferdinand and Josef did not get on. The emperor was a reserved man who never showed emotion to anyone but his beloved wife Sisi. While Franz Ferdinand…

Well, let’s just say the sulking and the volcanic temper had not improved with age.

Even though Karl Ludwig abdicated his claim, Franz Josef refused to name Ferdinand his heir. He claimed Ferdinand’s tuberculosis made him unfit to be emperor, that he might die at any moment. So, in 1892, Franz Ferdinand set off for warmer climes, desperate to relieve his infected lungs.

For the next two years, the archduke traveled the world, seeing the sights, taking the air… and, of course, shooting everything in sight. Ferdinand shot kangaroos in Australia, tigers in India, rare birds in Japan. When he returned in 1894, he actually brought two stuffed elephants he’d shot back with him.

Franz Josef’s response? He declared his nephew’s hobby was “mass murder.”

But while the trip may have been bad for exotic wildlife, it had been good for Franz Ferdinand’s lungs. The heir returned revitalized, better than he’d been in years. Barely had he reached the empire than he was attending balls in Prague.

It was here that the stuffy archduke met Countess Sophie Chotek. In the entire history of Franz Ferdinand’s life, there was almost nobody who remembered him fondly. He was too quick to anger, too prone to sulking, too much of an asshole.

The one exception was Sophie Chotek.

Somehow, this Bohemian countess brought out a side in this gruff, unlikeable man that no-one else ever saw. A side that was tender. Respectful. Maybe Sophie was the closest human equivalent Ferdinand ever found to one of his flowers. Something rare and radiant that made him feel things he otherwise never experienced.

Naturally, Franz Josef hated her.

Sophie may have been rich, but she was a mere countess. For the snobbish Habsburgs, that just wasn’t posh enough. So the emperor forbade their union. Pushed his new heir away. Just as he’d once pushed Rudolf away. Unlike Rudolf, though, Franz Ferdinand was willing to fight.

All through that miserable decade, the heir argued with the emperor.

He argued with him as Karl Ludwig succumbed to typhoid fever. As empress Sisi was felled by an assassin in Geneva. Finally, in 1900, Ferdinand hit jackpot.

After years of cajoling, Pope Leo XIII, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and Tsar Nicholas II all pleaded to Franz Josef on Ferdiand’s behalf.

Faced with the head of his religion, the head of his closest allied nation, and the head of the nation he desperately wanted to be allied with all appealing to him, Franz Josef at last relented. The emperor allowed Ferdinand and Sophie Chotek to marry that very year. But there was a catch.

Before he could tie the knot, Franz Ferdinand was made to sign an oath, excluding both his children from the line of succession and Sophie from all official ceremonies. It was a high price to pay. But it was also the only offer Franz Ferdinand would ever get. Reluctantly, he agreed.

It’s doubtful anyone realized it, but at that moment, the multiverse branched yet again, taking the empire ever further from peace, from survival. Franz Josef may not have realized it, but his obstinacy had just doomed them all.

The Spirit of Rudolf

“Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it”, is one of those misquotes that has been attributed to just about everybody. But, in the context of early 20th Century Austria-Hungary, it is absolutely something Franz Josef should’ve kept in mind.

Having contributed to Rudolf’s breakdown by isolating him at court and forcing him to marry someone he had nothing in common with, the emperor was now turning his guns on his heir.

The marriage of Franz Ferdinand and Sophie Chotek had been a personal insult to Franz Josef. He instructed everyone at court to ignore Ferdinand’s new wife. At the same time, he began pushing his nephew away from the business of government, castrating him politically.

Rudolf had tried to reform the empire but been sidelined. And now Franz Ferdinand was about to suffer the same fate.

Why did Franz Josef so singularly fail both his heirs? There’s a lot of debate about this, but one possible reason is that he ascended to the throne when he was just 18, and simply wasn’t aware that most future emperors needed guidance, needed teaching. When Ferdinand tried to follow in Rudolf’s footsteps and modernize the empire, he got neither of those things. The emperor just blanked him.

And this was a problem, because – at the dawn of the 20th Century – Franz Ferdiand was the only one with ideas for holding the Austro-Hugarian Empire together. Like Rudolf, Ferdinand had become obsessed with the issue of nationalism in the multi-ethnic empire.

But while Rudolf had tried to implement minor reforms, Ferdinand wanted to overhaul the whole system.

Franz Ferdinand’s plans ranged from splitting the empire into a United States of Austria, to elevating the South Slavs (AKA the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs) to joint-ruler status alongside the Austrians and Hungarians.

But don’t go thinking Ferdinand was a Rudolf-style liberal, oh no.

The man was a reactionary conservative who hated Hungarians, hated Slavs, wasn’t all that hot on Jews, and thought Austria had a God-given right to stomp all over its minorities.

He was, in short, a very unpleasant dude.

But here’s the thing about unpleasant dudes. They can sometimes do the right thing for the wrong reason.

Franz Ferdinad’s plans for liberalizing the empire, granting all men the vote, and giving each nationality more autonomy may have come from a cynical calculation that it was the only way to keep his family in power, but it really would’ve improved things for millions.

It’s not beyond the realms of possibility that a reformed, federal Austria-Hungary would’ve survived right up to today. But we’ll never know for sure, because Franz Josef nixed every single plan Ferdinand had.

In the court, these stifled reforms turned Franz Ferdinand into a laughing stock.

It was whispered in Vienna that the heir was clinically insane, that his family’s inbreeding had caught up with him. For a while, Ferdiand tried to brave the storm. But even this insanely unpopular man wasn’t immune to public opinion.

In the mid-1900s, Ferdinand and Sophie abruptly quit Vienna.

They retired to their home of Konopiště in what is now the Czech Republic and settled down to a life of domestic bliss. It was almost a happy ending. Together, the couple had three children; and Franz Ferdinand settled back into his old passion of horticulture, creating one of the world’s largest rose gardens.

In another time, in another place, that might have been the end of things: with Sophie a happy mother, and Ferdinand quietly pressing his roses by candlelight, all the cares of empire forgotten. But this was Europe in the early 20th Century, a tinderbox less than a decade away from exploding. For Franz Ferdinand and Sophie there would be no peace. The wheels were already in motion.

Their violent fate was waiting for them.

Death in Sarajevo

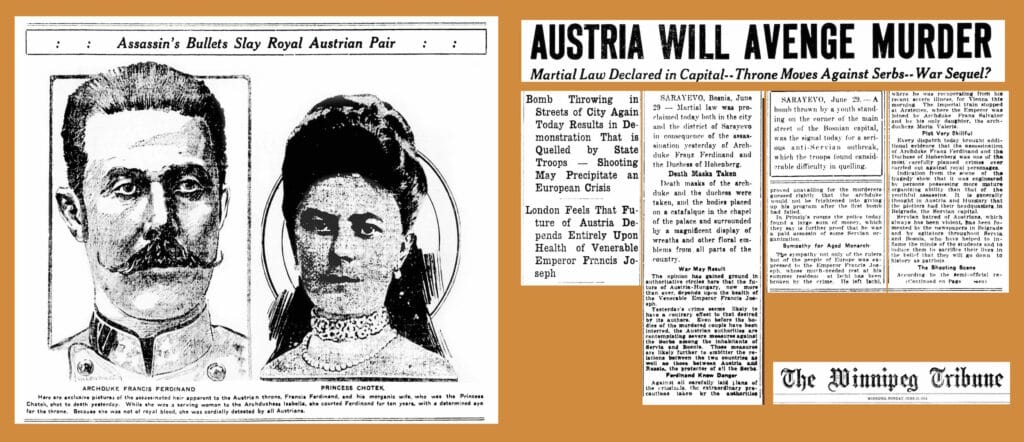

On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie disembarked from a train in the Bosnian city of Sarajevo and stepped into an open-topped car. It was a hot day and the river running through the center of the city was lower than usual. But as the motorcade whipped past, it wasn’t the river the archduke should’ve been looking at.

It was the crowds.

Near the city’s old Latin Bridge, Nedeljko Cabrinovic and Gavrilo Princip waited, anonymous faces amid the assembled masses. In the pockets of their heavy coats sat bombs and guns. Near their trembling fingertips lay cyanide capsules.

They and their comrades had one goal: to kill the heir of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. To understand why we need to quickly wind back Father Time’s videotape.

Remember when we told you Sarajevo was part of the decaying Ottoman Empire?

Well, fifteen years after Franz Ferdinand’s birth, in 1878, the Ottoman Empire had completely decayed in the Balkans, losing nearly all its territories. Into this power vacuum, the Austro-Hungarians had marched, taking over Bosnia on the strict understanding that they were only there to keep the region from imploding.

But Vienna and Budapest had no intention of ever leaving. In 1908, they’d officially annexed the region. But rather than passing virtually unnoticed, it had caused a European crisis. An outraged Russia had permanently turned its back on Austria-Hungary. In the Balkans, Serbs had declared the empire their mortal enemy.

And now Cabrinovic and Princip were determined to make the empire pay.

Interestingly, they nearly didn’t get their chance. The night before, Franz Ferdinand had had a premonition that all would not be well in Sarajevo. But it was his and Sophie’s wedding anniversary, and these semi-unofficial trips with minimal security were the only ones Franz Josef allowed Sophie to go on.

So here the couple were, speeding alongside the half-dry river in Sarajevo, blissfully unaware of the men waiting to kill them.

As the car roared past the Latin Bridge, Cabrinovic whipped out a bomb and hurled it. But the bomb bounced off the car and hit the police escort behind, blowing them up instead.

In a panic, Cabrinovic forgot his gun and tried to commit suicide by leaping into the river…

…only to land on the dried-out bank, missing the water and breaking his legs.

As Gavrilo Princip watched in a daze, the car carrying his and Cabrinovic’s target motored away at speed. He’d failed. Except, as you already know, he hadn’t. What came next was like something out of a tragic farce.

The car carrying Ferdiand and Sophie stopped at the City Hall, as scheduled. But rather than focus on getting the hell away from Sarajevo, everyone carried on like nothing had happened. Once the ceremony was over, Franz Ferdinand even insisted on driving back into town to check on the wounded.

As someone who’d been there that day later said:

“We all felt awkward because we knew that when he went out he would certainly be killed.”

Yet no one stopped the archduke from getting back in the car. No-one told the driver to take a different route in case more assassins were waiting. And no one raised a finger as Ferdinand and Sophie headed back towards the Latin Bridge, where Gavrilo Princip was still standing in shock, unable to believe he’d missed his chance to assassinate the Austrian heir.

One can only wonder how he felt when he saw the car motoring back toward him, like a moving target going round a shooting-range carousel, giving him another shot at the grand prize.

It was a shot Princip gladly took.

The first bullet hit Sophie, killing her almost instantly. The second thudded into Franz Ferdinand’s chest, turning his bright blue uniform a brilliant red. As the crowd set upon Princip, the car sped away from the scene.

In the back, Franz Ferdinand held poor, dead Sophie Chotek, whispering in her lifeless ear.

“Sophie, Sophie, don’t die! Stay alive for the children.”

As the blood seeped through Ferdinand’s tunic, a bodyguard asked if he was hurt.

“It’s nothing,” the heir said, irritable to the last. “It’s nothing… it’s nothing…”

Those were the last words Franz Ferdinand ever uttered.

As news broke that evening that the heir to the Austrian throne had been assassinated, Europe plunged into a state of shock. In every capital, in every embassy, people wondered what it might mean. If it even meant anything.

But make no mistake. This was old Europe’s 9/11, the moment that would change everything.

In just over one month’s time, the entire continent would be at war.

The Long March to War

Although the life of Franz Ferdinand ended that hot June day, his story didn’t.

In the aftermath of the assassination, Austrian intelligence reported the attack had been organized by the Serbian government. Vienna nearly invaded that same week. Today, some historians think this could’ve prevented WWI. Sympathy initially lay with Austria, and a quick strike might’ve been seen as justified.

But the realities of the empire meant Budapest had to be consulted first. And both capitals wound up dithering until the shock had faded, by which point Russia was reasserting its military alliance with Serbia.

In Vienna, Emperor Franz Josef agonized over what to do.

He’d now lost his second heir in a violent, unforeseen incident. But unlike Rudolf’s suicide, this time there was a physical enemy, someone the Austrians could get revenge on. By July, the drumbeat of war echoing over Europe was unmistakable. On the 28th, Franz Josef officially signed a document declaring war on Serbia. Austrian troops marched that same day.

Yet even now, WWI was not inevitable.

It wasn’t until Russia began to mobilize to defend Serbia that Europe hit the point of no return. The sight of Russia mobilizing scared the Germans, who in turn began mobilizing against the Russians. The French then got double scared and began to mobilize against the Germans, which led to the German decision to attack France first via Belgium, which in turn dragged Britain into the war.

It was the dominoes falling, one by one, adding up to a chain reaction that couldn’t be stopped.

By August, Europe was at war. It wouldn’t end until 20 million were dead, and Austro-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Tsarist Russia had all collapsed into dust. Not that Franz Josef lived to see it. The elderly empire died in 1916, halfway through the war.

It’s possible that, on his deathbed, he looked back on both Rudolf and Franz Ferdinand, his two dead heirs, and wondered if their reforms might’ve saved his empire.

The last time Franz Ferdinand appeared in history as anything other than the trigger for WWI. It was 1917. That year, a huge statue of him was unveiled in Sarajevo, on the very spot he was killed. It was a heartfelt tribute from the city’s Austrians. It was also a short-lived one.

After WWI ended and Austria collapsed, the statue was destroyed. Later, under Tito’s Yugoslavia, it was replaced by monuments celebrating not the murdered Franz Ferdinand, but his assassin, Gavrilo Princip.

Today, Franz Ferdinand has been almost entirely forgotten. Oh, sure, his name is famous, his place in the history books assured. But the Ferdinand we remember is not a full person, but a symbol. A single image of a portly man in silly clothes sat in an open-topped car, seconds before his death shattered an entire world.

His face and name may remain, but his soul has been forgotten.

It’s said that some men are born to greatness, while others have greatness thrust upon them. The life of Franz Ferdinand belongs to another, much-less known category. One of men who were not great, or even particularly notable, but without whom we wouldn’t have the modern world.

He may have been moody, he may have been hard to love. But Franz Ferdinand was also a human being.

Next time November rolls around and you see someone wearing a poppy, spare a thought for the accidental heir. For the man who, in death, unwittingly changed history.

Sources

Habsburg biography: https://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/archduke-franz-ferdinand-heir-throne

Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark: https://www.amazon.com/Sleepwalkers-How-Europe-Went-1914/dp/0061146668

Britannica Biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Ferdinand-Archduke-of-Austria-Este

Profile of FF: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/10930835/What-sort-of-a-man-was-Archduke-Franz-Ferdinand.html

Weird facts about FF: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/8-things-didnt-know-franz-ferdinand

Brief overview: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/months-past/birth-archduke-franz-ferdinand

Crown Prince Rudolf: https://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/rudolf-apprenticed-crown

Rudolf: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rudolf-Archduke-and-Crown-Prince-of-Austria

Mayerling Incident: http://www.historynaked.com/the-mayerling-incident/

1908 Bosnian Crisis: https://ww1.habsburger.net/en/chapters/1908-annexation-crisis

Excellent, in-depth account of the assassination in 1914: https://www.ft.com/content/293938b2-afcd-11e3-9cd1-00144feab7de

WWI timeline: https://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/firstworldwar/index-1914.html