Stroll down the cereal aisle at any grocery store and you’ll find a myriad of choices for starting your day. Healthy and unhealthy, packed with sugar or packed with bran, we’re not wanting for options. The idea of a breakfast cereal industry is one that’s taken for granted in today’s modern world, but it’s a surprisingly recent idea with a bizarre history.

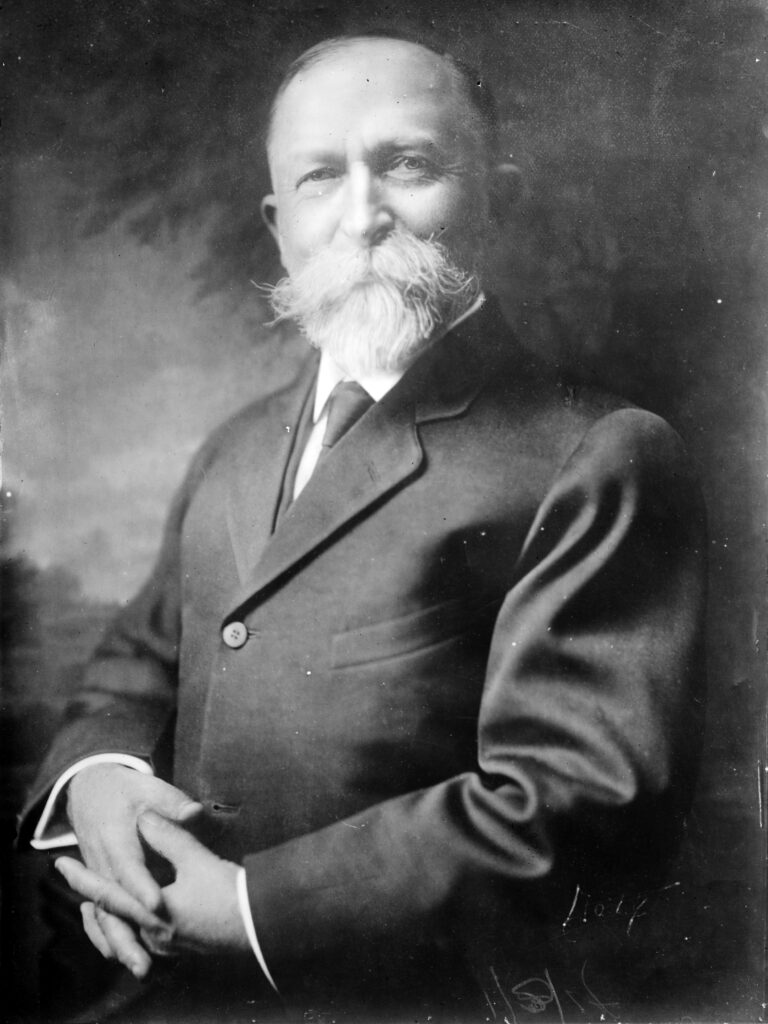

Kellogg is, of course, one of the first names that comes to mind when the conversation turns to breakfast. While official Kellogg’s history notes that it was W.K. Kellogg who founded the company first known as the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company — and who hired their first set of 44 employees — it was his brother, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, who was the driving force behind the development of breakfast cereal.

And it’s a tale they definitely don’t tell on the back of any cereal box. There’s devout religious teachings, a condemnation of sex and fulfillment of natural urges, a deep-seated distrust of conventional medicines, and a faith in radical treatments that today seem nothing less than barbaric. On one hand, Kellog was driven by a need to make the world a better, healthier place. But on the other hand, he also dabbled in things like eugenics and promoted the idea of sterilizing people he deemed undesirable. He was a complicated individual, showing us that the world — and indeed, history — is full of people who do the wrong things for the right reasons. And sometimes, an entire business empire is built on their shoulders.

The beliefs that built breakfast

To truly understand who John Harvey Kellogg was, we have to start with his parents. John Preston Kellogg and Anne Stanley were farmers, but they were also devout individuals who were living on the cusp of the foundation of a new religion. In 1852, they were introduced to the beliefs of a new religious movement that was spawned from events that took place — or, more accurately, didn’t take place on October 22, 1844.

That was an important date for a group called the Millerites, and they believed it was the day of a very literal Second Coming. They believed Christ was going to return to walk the earth once again, and when he didn’t, the date became known as the Great Disappointment. Religion is, of course, complicated and difficult to sum up quickly, but the gist of the story is that Christ’s apparent failure to return to earth divided followers.

Some followed a woman named Ellen Harmon, who claimed to have experienced a prophetic event in December of that same year. She said it had been revealed to her that the date was right, and she had been given a sign they needed to organize and travel the straight and narrow path… right into Heaven.

The group was following a set of rather disorganized beliefs and teachings when the Kelloggs were introduced to the movement, and it wasn’t until 1863 that they organized into the Seventh-day Adventist church. By then, the Kelloggs were already well established in the movement, having helped relocate the group to Battle Creek, Michigan.

John Harvey Kellogg was born in 1852, and was front and center in the burgeoning Seventh-day Adventist movement. When he was just 12 years old, co-founder James White — who had married the prophetic Ellen Harmon — invited the young Kellogg to learn all he could about the printing trade, with the ultimate goal of getting him to aid in the spread of their teachings via the printed word. Kellogg was fascinated by both the teachings and writings of the new movement, but also by other works. Earlier health reformers had been preaching things like temperance, abstinence, and vegetarianism all in the name of living a life that would bring the mortal human closer to God, and that fell in line with what the Adventists were just beginning to teach.

That was the beginning of Kellogg’s rise to the attention of Adventist leaders, and in order to make sense of what comes later in his life, it’s important to focus on where he was coming from and what beliefs he was building on.

Seventh-day Adventist tradition says that people have a moral obligation to lead a healthy life. Taking care of the physical form, they say, is the only way to guarantee complete service to God, and living the best, healthiest life possible includes things like forgoing alcohol and tobacco.

But there was a bit more to it in Kellogg’s day. Adventist leaders were critical of conventional medicine and wanted to train their own group of doctors who would have beliefs rooted in Adventism, but experience in practical medicine that would allow them to be critical while speaking from a well-informed position. So, Kellogg was recruited as one of a group of people sent to study first at the Hygieo-Therapeutic College in New Jersey, then later at the University of Michigan Medical School.

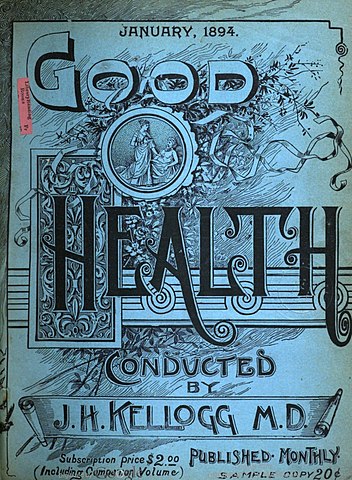

Kellogg didn’t aspire to be a doctor in the traditional sense; instead of treating illness, he wanted to help prevent it. He earned his M.D. from New York City’s Bellevue Hospital Medical College in 1875, and by that time, he had already published a cookbook focused on improving dietary habits, authored a work on the importance of vegetarianism, and took a position he would hold until he died, as editor of a monthly Adventist periodical he later named Good Health.

The Battle Creek Sanitarium

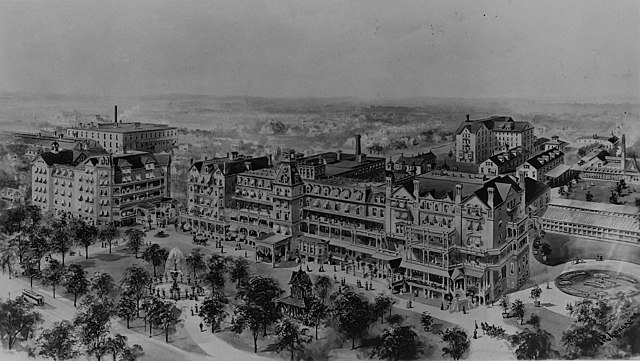

In 1876, Kellogg was appointed the superintendent of a facility called the Western Health Reform Institute, which was quickly renamed the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Over the next few decades, Kellogg and his brother, Will, would oversee the development of this midwestern facility into a globally-recognized destination, part resort, part medical facility, and part retreat of the rich and powerful.

That’s not an exaggeration, either. At the height of its popularity, the facility welcomed between 12,000 and 15,000 new patients each year, and some of those faces changed history. Among the patient list were names like Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, Warren Harding, Booker T. Washington, and Sojourner Truth. Even Amelia Earhart stopped in for a little R&R before major flights, a practice that came to be known as “taking the cure”.

The facility was impressive, and “impressive” is putting it mildly. In addition to a 15-story tower with 1200 bedrooms, there were hundreds of baths, a lobby the size of a football field, indoor gardens, and to give an idea of the scale of the place, there were a full five acres of marble-covered floors. The sanitarium had its own power plant, a staff of doctors, nurses, orderlies, masseuses, and at the head of it all was the good Dr. Kellogg, who met with each and every patient who got off the train and was delivered into his care by liveried coachmen.

It sounds absolutely brilliant, but here’s where things start to get… weird. Kellogg’s sanitarium was outfitted with all the equipment he could possibly need to get patients in tip-top shape, but treatments weren’t necessarily ones people were thrilled to be prescribed.

One of the most popular rooms was the sanctum sanctorum, which was filled with — and yes, this was a real thing — enema machines. Each machine was capable of pumping 15 quarts of water you-know-where in just a single minute, and if there’s anything that will encourage you to reach for that high-fiber cereal, it’s that. In extreme cases where that wasn’t enough to get patients having their recommended 4 bowel movements per day — a number Kellogg reached after watching apes — they were prescribed yogurt. First, a pint of yogurt per day was added to a patient’s diet, then they were given a yogurt enema.

Why? Cleanliness. Kellogg was obsessed with it. Take those marble floors. They weren’t there for appearances, they were there because they were a surface where “germs and vermin can never find a lodging.”

Enemas weren’t the only commonly prescribed treatment patients could expect to experience. Kellogg was also a proponent of light therapy, and he was the inventor of something called the electric light bath. Essentially, patients were put into a cabinet lit with light bulbs, and it was thought to be a cure for a number of ailments, everything from writer’s cramp to syphilis. And it’s also worth noting that this one isn’t as far-fetched as it seems at first glance — some of Kellogg’s work laid the groundwork in using light therapy to treat depression.

Kellogg was also interested in the healing powers of electricity, and prescribed regular sinusoidal current treatments to some patients, particularly those diagnosed with tuberculosis and lead poisoning. The mild electrical currents were applied with the help of a device he made himself from a telephone, and sometimes the current was applied to the skin, and sometimes, it was applied straight to the eyeballs in an attempt to treat ocular disorders.

And that wasn’t the only machine he invented. The sanitarium was filled with devices that would shake, vibrate, slap, and even beat patients to various ends. Some were designed to stimulate the bowels, others were thought to help improve circulation. And some of the good doctor’s wealthiest patients had their own versions of his machines installed in their homes — Calvin Coolidge even had one in the White House during his term as president.

It’s also worth noting that people loved going for treatments at the clinic, affectionately known as the San. Just a few years after Kellogg took over, he went from treating 300 people a year to 1200, and numbers just kept climbing. He truly believed in what he was doing, and even advertised in major magazines to help get the word out about his miraculous treatments. An advertisement ran in Good Housekeeping in 1907, and boasted of the 46 different kinds of baths at Kellogg’s disposal. Some were ordinary, like foot baths, some were odd, like the light baths, and some could only be described as extensive. Patients complaining of ailments like chronic diarrhea, various skin conditions, and mental illnesses might be prescribed a continuous bath.

And what was that? It was a normal bath, taken in a tub, but a patient could be instructed to stay there for days, or even months. The more you think about that, the worse it gets, but it wasn’t the worst thing Kellogg ever prescribed — that dubious honor belongs to his cures for what he called “the solitary vice”. Mastubation, he believed, would ultimately lead to things like heart disease and insanity, so to stop patients with a chronic habit, he did terrible things. Boys would be bound, tied, or forced to wear cages, and if that didn’t work, they were circumcised without anesthetic in hopes that the pain would discourage further acts. Girls were not exempt, either, and some were burned with acid or subjected to surgery to remove part of the genitals. Kellogg was devoted to health and godliness, and he was extreme.

Amid these cures, Kellogg also focused on something that he believed desperately needed an overhaul: breakfast.

Changing the way America ate

This is where we go back to the heart of Kellogg’s Seventh-day Adventist beliefs. Co-founder Ellen Harmon White wrote that the truly devout would follow a vegetarian diet, because fruit and vegetables were seen as God’s gift to mankind. She taught that people should eat foods that could be consumed in their natural state: fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains. Kellogg followed that belief, at a time when breakfast was about as unhealthy as you can imagine.

Kellogg, remember, was living at a time when most people started their day with the previous nights’ leftovers. Some of the most common breakfasts involved meat and potatoes reheated in a pan with whatever fats they had congealed in. Heavy meals of salted and cured meats were also popular, and anything grain-based was difficult. It was time-consuming and labor-intensive, and it meant getting up before the sun, stirring, and cooking raw grains into gruel. In 1858, Walt Whitman wrote that indigestion was “the great American evil,” and it’s no wonder. Gastrointestinal distress was so common and so frequent there was one catch-all term used to describe all the symptoms: dyspepsia.

Kellogg’s attempts at overhauling breakfast were practical: he wanted something that was easy for someone to prepare, and just as easy on the stomach. He and his brother spent years experimenting in their own food lab, trying to come up with vegetarian diets that would be easy for any patient to digest, and that were boring. The boring part was on purpose. Part of the theory was that bland, boring food would not only keep their patients walking the straight and narrow right up into heaven by consuming food in the way God meant but also that it would prevent them from getting too excited and overstimulated.

They did have some success, starting with protose. It was essentially an early version of a veggie burger, tasted of peanuts, and was both given to sanitarium patients and sold through mail order. He also developed something he called “granula”, until another 19th-century foodie claimed the rights to it, and forced him to change the name. Kellogg’s granola — bars of cornmeal and oatmeal that were baked then ground into bits — became known as granola.

Just how the Kellogg brothers made their leap into breakfast cereal is a bit of legend and a bit of history, and the story goes that they mistakenly left wheat-berry dough on the counter overnight. It was stale the next morning, and when they rolled it out and toasted it, they got some crunchy flakes that became a huge hit with patients.

Kellogg handed the marketing of their breakfast foods off to his brother, who was working as the sanitarium’s bookkeeper. But all was not well at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. Debts were mounting, church elders were concerned by a curriculum they saw as getting far away from their Seventh-day Adventist roots, and when a fire swept through the compound they told him they wouldn’t be rebuilding.

At the same time, Kellogg’s brother, Will, was pushing a practical way of getting more people to buy their corn flakes. He wanted to add sugar, an addition that Kellogg found abhorrent. Will left to found the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, and Kellogg tried his own hand at selling the flakes they’d invented together. Will sued, won, and went the business route while John Harvey Kellogg stayed on at the San.

It’s also worth a quick aside here to say that Kellogg’s wasn’t the only cereal company to grow out of this era. One of the Kellogg’s recurring patients was a man named Charles William Post, who stayed at the sanitarium in the 1890s during periods of mental breakdowns and stress. He saw what they were doing, picked up on the trend, and went on to sell the cereals Postum and Grape-Nuts through his own company. Post’s company is generally credited as being the force that pushed Kellogg to develop better products with a longer shelf life, and as for the competition, Kellogg would comment that he “was not after the business; I am after the reform; that is what I want to see.”

Kellogg held his patients to strict rules, and that included sticking to his bland, vegetarian diet and a requirement that they chew: a lot. A devotee of Horace Fletcher, he prescribed to the theories of Fletcherism that dictated chewing each bite of food 40 times would aid in digestion. He was often heard leading diners in singing his “Chewing Song,” and there’s a bit of a footnote to this. Not all of his patients were happy with the diet and the philosophy of no alcohol and no smoking. Fortunately for them, a particularly brilliant entrepreneur set up a place just down the street, called it the Red Onion Tavern, and served steaks, cigars, and whiskey to patients… along with a promise to get them back out the door in time to beat the sanitarium’s 11 pm curfew.

Life beyond the sanitarium

While Kellogg spent much of his life working at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, meeting with patients while wearing a distinctive — and clean — white suit with a cockatoo on his shoulder, there was more to his life than just a never-ending parade of patients. He married Ella Eaton in 1879, and while they had no biological children they fostered more than 40 kids and officially adopted several. She played an invaluable role in his dietary experiments, and she also introduced him to new social spheres of influence, like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.

He was also an adept surgeon, spending some time studying abdominal surgeries in London and Vienna. By the time he finally put down his surgeon’s scalpel at 88 years of age, he had performed around 22,000 procedures.

Kellogg had a falling-out with his Adventist church leaders in 1907 and was ultimately expelled from the church. They believed that he was using church funds for medical research and education instead of evangelism, and it was an affront they could not stand for. Kellogg still kept control of the sanitarium, though, and in addition to remaining a consistent, controlling presence there, he also expanded his reach to open schools for hygiene, nursing, home economics, and physical education on sanitarium grounds.

He served on the Michigan State Board of Health, wrote around 50 books on the subject of health, issued some of the first warnings on the dangers of smoking, and this is about to take a strange twist, because he went on to co-found something less-than-admirable: the Race Betterment Foundation.

That was exactly what it sounds like: an organization dedicated toward maintaining the superiority of certain races by selective breeding. Remember all those children that he and his wife fostered? It wasn’t entirely out of the goodness of his heart, as the Eugenics Archives notes that most of the children were, in one way or another, deemed “undesirables”. Kellogg was hoping to make some sort of discovery on the influence of environment on heredity, and don’t worry, it gets even worse.

The Battle Creek Sanitarium was at the very center of the spread of eugenics throughout the US during the early 20th century, and Kellogg devoted about 30 years of his life (and a ton of his own money) to the idea that excluding people with certain genes from the pool of breeding humans would improve humanity as a whole. Exclude them how? While he was serving on the Michigan State Board of Health, he successfully lobbied to pass a law that would call for the “sterilization of mentally defective persons”, a law that led to the involuntary sterilization of at least 3,800 people in the state.

Kellogg — and other believers — preached that encouraging only certain people to reproduce would end all the ills the human race suffered from, from poverty to criminality to, quote, “feeblemindedness”. That superior race was, of course, the Caucasian one and yes, there was a very real association that would later form with the Nazi party.

Kellogg began to completely embrace eugenics after his falling-out with the Seventh-day Adventists — a group who, incidentally, believed that all life was a gift from God. He became obsessed with the idea that if things continued as they were, mankind would begin to decay and degrade in quality until finally, it simply ceased to exist.

In 1914, Kellogg had become good friends with other leading figures of the eugenics movement, like Charles Davenport, founder of the Eugenics Record Office. They held the first Race Betterment Conference at the San, and one of his guest speakers was a former patient — Booker T. Washington was there to try to talk to attendees and convince them that everyone should be treated fairly and equally. The San, incidentally, was always a segregated facility.

Conference attendees did more than just examine and measure around 5,000 children as a part of the “Better Babies” contest, they also made it clear they were going to start pushing their ideas further into the US. The second conference was held in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exhibition, and it took the society’s beliefs — clearly illustrated by charts highlighting the differences between “superior” and “degenerate” races — and put them squarely in front of 18 million visitors. He campaigned for the establishment of nationwide legislature similar to what he had established in Michigan, and even proposed a registry where people would be given “pedigrees,” and parents who fell within the established guidelines for “racial hygiene” would be eligible for awards.

There were a few things that brought down the eugenics movement, and the first was the extremes of Nazi Germany. Even before that, the troubles brought by the Great Depression proved to many that poverty and hardship had nothing to do with genetics, but eugenics legislation was still in place — and sterilizations were practiced — into the 1970s.

As for Kellogg, he died in 1943. He nearly hit the century he had always proclaimed he would live to: he was 91 years old.