Not many remember the name of Mary Mallon. If not for tragic circumstances, a strange immunity, and her position at the center of an outbreak of disease, it’s likely that she would have faded into obscurity as just another ordinary immigrant who gave up her homeland for the promise of America in the mid-1880s. Mallon was just a teenager when she left Ireland and headed west, landing in New York City in 1883 or 1884. She had connections there, at least, an aunt and uncle she lived with until she found her feet.

If that was all there was to the story, history wouldn’t remember her. She would have been one of millions of Irish who emigrated to the US in the 19th century, a time when an estimated 50 percent of the country’s population picked up roots to try to make a better life elsewhere. But Mallon was carrying a deadly disease with her, and marked her as Typhoid Mary. But there’s more to her story than just a gory nickname, and remembering her as just as a carrier of disease doesn’t quite do her credit.

What is typhoid fever, anyway?

Since typhoid fever is one of those olde-timey diseases that isn’t talked about much in the modern, industrialized world, this conversation deserves a short foreword on what exactly the disease is. It’s caused by the bacteria Salmonella typhi, and most of the time, it’s passed from one person to the next through food or water that’s been contaminated. In some cases, being in close contact with someone that’s infected can spread the disease, too.

Symptoms can take up to a week to develop, and they’re generally unpleasant. The infected have to contend with a wide range of disease markers, including fatigue, muscle aches, abdominal pains, swelling, and sweating, ranging all the way up to fever and extreme gastrointestinal distress. Without treatment, the disease can progress to delirium and the so-called typhoid state: laying there, too exhausted to move, eyes half-open. It’s at that stage when other complications can develop: some might start suffering from hallucinations and paranoid psychosis; others might develop inflammation of the heart, pancreas, or brain. The most serious complication is intestinal bleeding, which, in some cases, can lead to holes in the intestines.

Typhoid is treatable today, but even modern vaccinations aren’t 100 percent effective. The cause of typhoid was confirmed in 1880, after years of attempts to document exactly how contained instances of disease can turn into epidemics. Typhoid had about a 10 percent fatality rate at the turn of the 20th century, and the first vaccine wasn’t developed until 1911. That’s five years after Mary Mallon was hired to cook for a well-to-do New York banker named Charles Henry Warren and his family.

Typhoid Summer

Not much is known about Mallon’s early life in Ireland, or her first years in the US. She was born in County Tyrone — one of the poorest areas of Northern Ireland — on September 23, 1869, and left her homeland for the US when she was only 14 or 15 years old. There was nothing unusual about her; in fact, she followed the normal route of settling in with family members who had made the crossing before her, then finding work as a domestic servant. Things started to change in 1900, when one of her employers discovered she was a talented cook. They put her to work in the kitchens, and it was a move that changed her life, and the lives of those who employed her.

Mallon worked for eight families in the years between 1900 and 1907, and where she went, typhoid fever often followed. At the time, typhoid was an illness associated with crowded and poor urban communities with nonexistent sanitation and little access to fresh drinking water. Mallon, however, was working for some of the most affluent families in the city, which were not exactly the sort of families that tended not to suffer from afflictions like typhoid. Doctors did notice they were unusual victims, but remained baffled by the outbreak of illness in homes where there seemed to be no logical explanation for it.

Mallon’s peers became sick at seven of the eight jobs she held in those years. At least 22 individuals fell ill, and at least one died. There’s nothing that indicates Mallon initially had any idea the illnesses were connected to her in any way, and she continued to cook for various families. Because she did move around a bit, and because she never left a forwarding address, it took a while before anyone could connect the dots.

In the summer of 1906, Mallon was hired to be a summer cook for Charles Henry Warren and his family. They had rented a house on Long Island and in August, one of his daughters took ill. It was, of course, Typhoid, and it wasn’t long before her sister, mother, a gardener, and two maids were also sick.

The owner of the house was George Thompson, and he was understandably worried; no one would want to vacation there if it gained a reputation as a place where an entire family could fall mysteriously ill. They were afraid the area water source was contaminated, and knew they had to find out exactly what happened before they could rent the property again.

Thompson looked for and found a professional to get to the bottom of things. He hired New York City Department of Health sanitary engineer George Soper to find the source of infection, and he knew exactly what to look for, as he had specialized in the study of typhoid outbreaks. At first, Soper thought the freshwater clams that had been served to the family were a likely source, but not everyone who developed typhoid had eaten them. Eventually, he honed in on Mallon as another potential source for the disease.

His theory was quickly confirmed. Mallon moved on from the Warren family and showed up next as a cook in a home on Manhattan’s Park Avenue. That’s where Soper followed her, and when he met her.

Confronting Typhoid Mary

In order to confirm Mary Mallon was, indeed, a carrier of typhoid, Soper knew he needed to have her bodily fluids tested for presence of the bacteria. It’s hard to imagine just how awkward that conversation had to be; when Soper introduced himself to her and asked her to provide samples, well, he described the encounter like this:

“I was as diplomatic as possible, but I had to say I suspected her of making people sick and that I wanted specimens of her urine, feces, and blood. It did not take Mary long to react to this suggestion. She seized a carving fork and advanced in my direction. I passed rapidly down the long narrow hall, through the tall, iron gate, and so to the sidewalk. I felt rather lucky to escape.”

Now, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to vilify Mallon. We know she was a carrier of Typhoid, but she almost certainly did not. She had never developed the disease herself, and she did, at one point, voluntarily subject herself to testing for the bacteria. The chemist who performed the tests — who was a respected professional — declared she was free of any sign of disease. It’s suspected the tests were performed when she was in a period of remission, which certainly didn’t make things any easier on either her or Soper.

Just imagine: a stranger appears out of nowhere and accuses you of being responsible for spreading disease and sickness everywhere you’ve worked. You are, allegedly, responsible for deaths, despite the fact that you feel fine and have never been sick. At one point, a doctor has even told you that you’re fine. It’s no wonder that Mallon was less than willing to submit to more tests, amid rumors that would put her entire livelihood on the line.

There is another element at work here, too, that may have attributed to Mallon’s violent outbursts when confronted. The late 1800s was a time when the Irish were emigrating to the US in droves, fleeing oppression and starvation in their homeland. Some made the journey on so-called “coffin ships,” packed with desperate immigrants and so filled with disease and death that an estimated 25 percent died before they completed their journey. Their bodies ended up at the bottom of the Atlantic.

Those that did reach America’s shores were starving and destitute by the time they got there, and there were a lot of them. Anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment was strong, and while there were some groups who offered charity to the refuges, there were more that whispered of a secret plot orchestrated by the Vatican to instill Catholicism in America as the dominant religion. The Irish were condemned for supposedly taking jobs from Americans and gallivanting as drunken criminals. Politicians who railed about the Irish nuisance were preaching loudly from their pulpits to a public that was more than happy to listen. Homes and churches were burnt, and mob violence took lives.

It was only in the 1880s that some politicians began to see the large numbers of Irish as valuable allies, but signs of “No Irish Need Apply” were still fresh in everyone’s memory. For Mallon, it very well could have felt that this was just one more way her new home was persecuting her for the accent she kept throughout her entire life.

Soper couldn’t give up, though, as he was sure he was right.

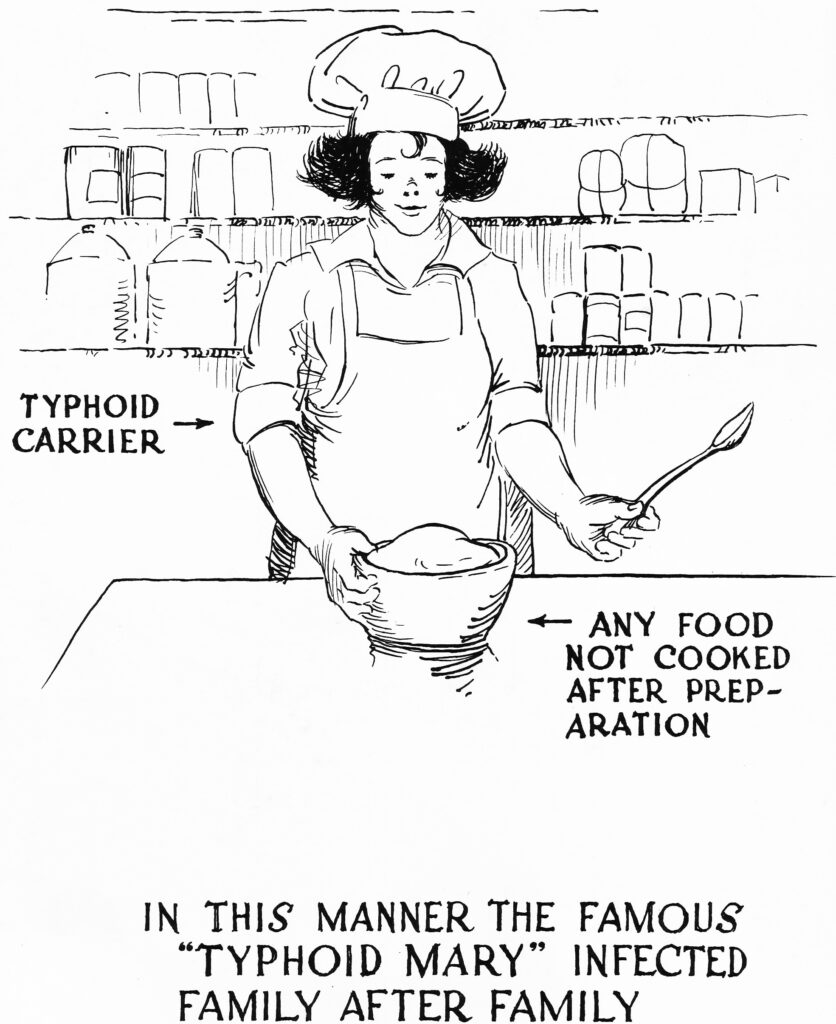

Still, Soper knew he was right and couldn’t walk away. He discovered exactly what it was that Mallon had served to get everyone sick: ice cream with fresh peaches. Heat may have destroyed the bacteria in other foods, but the uncooked peaches and Mallon’s unwashed hands were the perfect way for disease to spread.

In 1906, there were 3,467 reported cases of typhoid, and 639 of them were deadly. The actual number of cases was probably much higher, and if Typhoid Mary was spreading it everywhere she went, it was only a matter of time before the city had a potential outbreak on its hands.

At the time, Soper was familiar with the idea that people infected with disease could pass bacteria on to others through various bodily fluids. But since Mallon wasn’t sick and never had been, this was completely different from anything he’d seen before. By the time Soper caught up to her at her new job in Manhattan, there were already instances of typhoid in the household she was cooking for; one servant was infected, and the family’s only daughter was dying. So, he followed her to the boarding house she was living in and confronted her again, with no more luck than the last time.

After he was turned down for fluid donations a second time, Soper requested help from the New York City Health Department. He gave them a warning: in this case, they needed to be prepared to use force. The Health Department gave her one more chance to peacefully agree to submit to testing, and sent Dr. S. Josephine Baker to see her. When she still refused to cooperate, they sent the police.

Mallon tried to flee, but was eventually found, forced into an ambulance, and taken to the Willard Parker Hospital in what Dr. Baker described as a “wild” ride, one where Dr. Baker was forced to sit on her the entire way to help restrain her. She wrote, “…it was like being in a cage with an angry lion,” and it was no wonder she struggled. Police had carried her into the ambulance after a five-hour chase, and Mallon was convinced she had done nothing wrong.

Mary Mallon enters into medical history

Once Mallon was transferred to the care of a hospital, her bodily fluids were tested repeatedly — three times a week, from March to November — for traces of the bacteria that causes typhoid. Most of the tests confirmed the Typhoid bacteria was there, but there were still some tests that came back negative, which explains why she might have had a clean test prior to Soper’s intervention.

It wasn’t long before Soper found himself sympathizing with Mallon. She hadn’t infected people on purpose, after all, but she was still dangerous. And now, she was being held in a small, uncomfortable hospital room, under lock and key, while she herself was of perfectly sound mind and body. He tried talking to her, getting her to cooperate, even suggesting she could have her gallbladder removed, as it was a nonessential organ that was probably the source of the infection. But she refused to talk to him. She stayed in custody for a full two years before she sued for her release.

Mallon argued in court that she had never been sick, but the courts viewed the findings of the medical research far more compelling, and refused to release her. That was, they said, largely because they didn’t want to bear any responsibility, should anyone else get sick or die from contact with her. It was another eleven months before Mallon made a deal with the Health Department: she could go free as long as she checked in with them every three months, and never cooked or handled food for others again.

Mallon agreed, was released, and promptly disappeared.

Here’s where things get a little dicey. Mallon did spend some time working in other professions, and she did get jobs in places like laundries, where she would have been no danger. But she found it almost impossible to support herself, and the temptation to return to cooking — which paid a lot more — was too high. So she went back in the kitchen, where she continued to cook and continued to infect a lot of people. Soper was officially off the case, but he continued to keep an eye on her. She popped up cooking under the pseudonyms Mrs. Brown and Marie Breshof, finding work in a fancy hotel and a sanitorium, both in New Jersey, along with a hotel in Southampton and a restaurant on Broadway. It’s impossible to tell just how many cases Mallon caused, but there were a lot. It was during this period that the press had officially christened her Typhoid Mary.

But here’s the thing. There’s no real evidence that suggests Mallon ever truly believed that she was the cause of all these instances of typhoid fever at the time she was first arrested and diagnosed. She was the very first example of a completely asymptomatic patient ever studied. If the medical community didn’t understand the mechanics of what was going on, how was Mallon supposed to?

It’s also suggested that there was another massive oversight in Mallon’s case. When she was released, she was told not to cook, and to take extra care when it came to hygiene. But she was never given any sort of specific instruction on how to properly disinfect herself and keep the bacteria off her hands, and she was never given any kind of retraining or direction on other ways she could support herself. There was no welfare system or aid available. Mallon assumed authorities were simply trying to label her a scapegoat for the outbreaks; she didn’t seem to think she was actually doing any harm when she returned to cooking.

The Question of Confinement

Mallon was initially released in 1910, and it wasn’t until five years later that a man named Dr. Edward B. Cragin approached Soper. He was an obstetrician at the Sloane Hospital for Women, a facility that had recently had more than 20 people fall ill to typhoid. He had a suspect and a sample of her handwriting, and asked Soper if he could identify their cook. He could. It was Mallon.

Soper advised him to reach out to the Health Department, and he did. Mallon was arrested and sent to quarantine on North Brother Island, an island in the East River that was home to a hospital and quarantine facility built in 1885. It was home to patients suffering from illnesses like tuberculosis, smallpox, yellow fever, and, of course, typhoid. Mallon would live among them until her death in 1938. Instead of feeling relief, Soper painted a heartbreaking picture of a woman who no longer fought against her own confinement. He wrote:

“…she had been advertised to the world as a dangerous person and had been treated worse than a criminal, and yet she had not been guilty of the least violence toward anybody.”

Mallon seemed resigned to her lot in life, finally admitting to herself that there was a wave of typhoid that swept along behind her wherever she went. She was not the same person when she was apprehended the second time, and there was little left of what Soper described as her “almost pathological anger.” She settled into her confinement willingly enough, and they gave her a job in the laboratory, where she ran medical tests. They even gave her permission to visit the mainland, where she regularly headed into the city. She always came back.

If she seemed resigned to her later confinement, it was a resignation she hadn’t felt in her younger years. Most of what we know of Mallon is through the writings of Soper and other medical professionals, although there are a few of her letters that have survived. In one, she describes being so distraught over being arrested and confined to a hospital for the first time, that she developed an eye twitch that led to the paralysis of one eye — a condition which went untreated. When she was given medication, she complained that she didn’t need it: it was mainly used to treat kidney issues, and she didn’t suffer from those. She wrote of doctors that told her she needed to have her gallbladder removed, then admitted to her that the surgery might not make a difference.

And she wrote: “I’m a little afraid of the people… I have been in fact a peep show for everybody. Even the interns had to come to see me and ask about the facts already known to the whole wide world. The tuberculosis men would say, “There she is, the kidnapped woman.” Dr. Park has had me illustrated in Chicago. I wonder how the said Dr. William Park would like to be insulted and put in the Journal and call him or his wife Typhoid William Park.”

It brings up an important question: did Mallon deserve to be vilified to such an extreme extent? Should she have been advertised as cracking skulls into a frying pan, as at least one illustration showed her doing? Or was she simply a victim of typhoid in her own way, too?

Unraveling the Mystery of Contagion

Mary Mallon was credited with directing spreading typhoid to at least 50 people, and three of them died. She’s even been named as the Patient Zero who likely started a typhoid outbreak in 1907, one that ultimately escalated to around 3,000 cases. Even though she’s the one most infamous when it comes to healthy people who have had the potential to spread a deadly disease, she was far from the only one.

By the time she died, more than 400 others had been identified in New York alone. In fact, somewhere between one and six percent of those infected with the type of salmonella that causes typhoid become healthy carriers, and it’s a huge problem the medical world hasn’t known too much about until recently. It wasn’t until 2013 that studies done by Stanford University School of Medicine researcher Denise Monack yielded some insight into demonstrating the mechanisms by which bacteria might infect a person without making them ill.

Figuring out the mechanics of just how it all works could lead to the development of a treatment that would block typhoid’s ability to hitch a ride in a seemingly healthy host, just as it did to Mallon. Today, there are a lot like her out there. Typhoid impacts around 16 million people a year across the globe, and even on the low end, that’s 160,000 people capable of spreading infection just like Mallon did.

Typhoid Mary died alone. Soper wrote about her death after he was fairly certain he had tracked down her sister, though he could never conclusively prove their relation.

On Christmas morning in 1932, she was discovered on the floor of her cottage, paralyzed from a stroke. She was moved to the hospital, where she lived until her death on November 11, 1938. Afterwards, there were advertisements taken out in several newspapers for the span of a month, appealing for relatives to come forward to claim the little money she left behind. No one ever did. Only nine people attended her funeral, and no one followed her to witness her burial at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx.

There’s a bit of rumor surrounding her death as well. An autopsy was said to have turned up a high concentration of bacteria in her gallbladder. If she had agreed to the operation to remove it, would she have been cured? It’s entirely possible, the rumor implies, but it’s not that clear-cut a case of regret. Some researchers — including Soper — say there never was an autopsy, and the tale is retold to help justify her imprisonment. Which is true? It’s impossible to say.