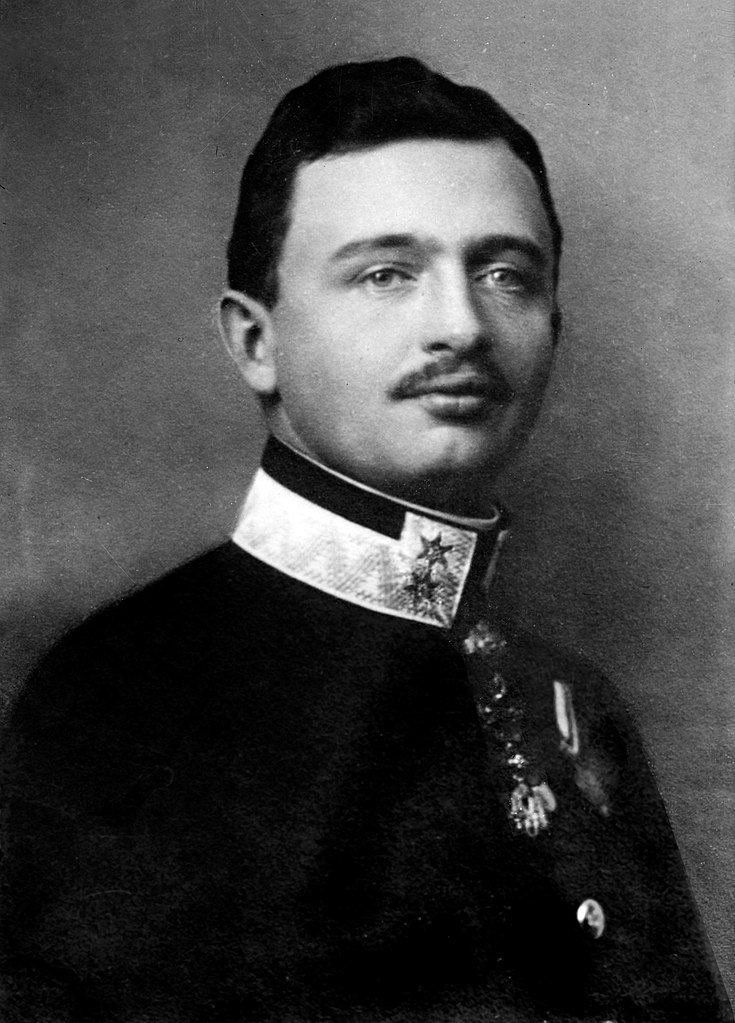

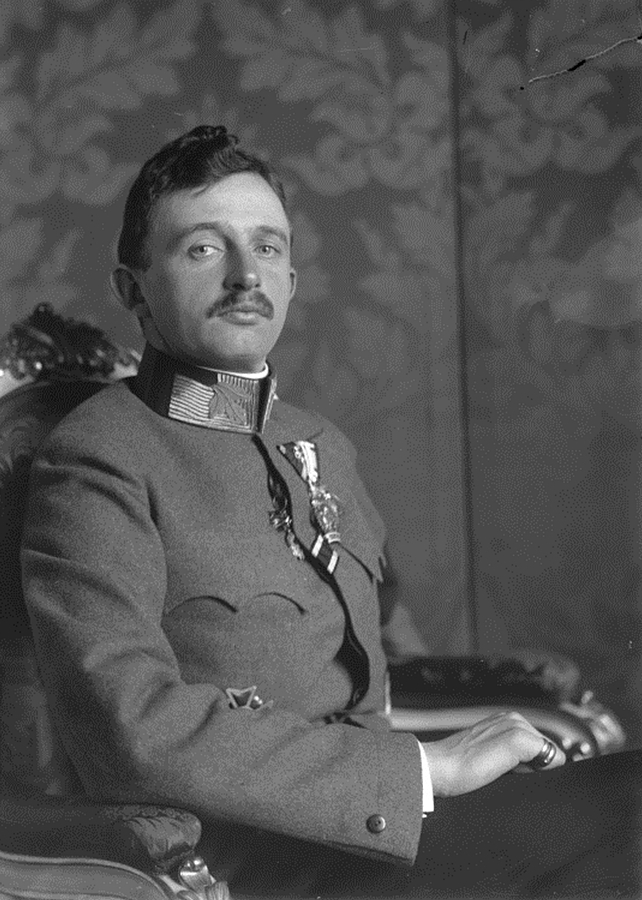

He’s one of the five longest-reigning monarchs in the history of the world. Emperor Franz Josef ruled over first Austria and then Austria-Hungary for almost precisely 68 years. Coming to the throne on the back of a revolution aged just 18, his reign coincided with some of the most-important events in European history. It was while Franz Josef was emperor that the Second French Empire rose and fell, that Germany was forged by blood and iron, and – most strikingly – that the events unfolded that would pave the way for WWI.

Yet Franz Josef was more than just a mere observer. Under his watch, Vienna became a cultural powerhouse, gifting the world Freud, Klimt, Schiele, and Wittgenstein. He oversaw the creation of one of the greatest multinational empires in history… and then lived long enough to sew the seeds of its destruction. A cipher to many, a semi-mythological figure to others, this is the life of Franz Josef, Europe’s last great emperor.

Countdown to Revolution

If you were suddenly blasted back in time to 1830, you would find yourself in a very different world. Back then, there was no such thing as Italy. Germany was 39 weak states locked into an alliance known as the German Confederation.

But the biggest difference you’d see would be the great, round blob slap bang in the middle of Europe. The blob covering not just northern Italy, but modern-day Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia, plus parts of Poland, Ukraine, and Romania. Known as the Austrian Empire, it was this imperial blob that Franz Josef was destined to rule.

Born on August 18, 1830, Franz Josef couldn’t have come at a better time. His grandfather, Emperor Francis I, was nearing the end of his life, and the line of succession was far from clear. While Francis had two sons, the future emperor Ferdinand I and Franz Josef’s own dad Francis Charles, neither of them had so far produced an heir.

So when young Franz Josef emerged, kicking and screaming into the light of day, the entire Habsburg royal family gave a collective sigh of relief. They finally had their future emperor!

Great though this was from a dynastic perspective, it was less great from the point of view of baby Franz Josef. From the moment he could talk, the young boy was forced to stuff his brain with all the knowledge a ruler could possibly need. This meant mastering military strategy. European history. It meant becoming fluent in not just German, French and Latin, but also Austria’s minority languages like Hungarian, Italian, Czech, and Polish.

Under the watchful eye of his ambitious mother, Archduchess Sophie, young Franz Josef was forced to spend nearly every waking moment studying, his progress meticulously monitored by Austria’s shadowy puppetmaster Metternich. As a result, the boy grew up to be both obsessed with duty, and utterly lacking in imagination.

For his part, Metternich considered this a win. As far as he and Archduchess Sophie could see, their precious heir was shaping up to be the God-fearing military man they wanted running the empire.

Little did they know that empire would soon be forced to fight for its very life.

Revolution!

There’s a game you can play when your job is producing history videos, and that game is to see how far you can get into the biography of any 19th Century figure before you have to mention 1848.

That’s because 1848 is the year Europe exploded. It started in February, when a French government ban on banquets lit the spark on a massive pile of dynamite marked “Decades of Public Resentment”. The flames from the subsequent blast quickly ignited another box of TNT marked “Decades of Austrian Resentment,” which in turn ignited another box marked “Hungarian Resentment,” and another marked “Italian Resentment”, and so-on.

It was a chain reaction of revolution. A series of wildfires that combined into a European inferno.

And it would nearly consume young Franz Josef.

At the moment the sparks from France’s 1848 revolution landed on Vienna, Franz Josef was a 17 year old lad, and his uncle Ferdinand I was on the throne. The revolutionary fire that blew up on March 13 would change all that. That day, students excited by the news from Paris gathered in Vienna to demand a new, liberal constitution. In panic, Metternich ordered cavalry to attack the crowd, triggering a riot.

By 9pm that night, Austria’s puppetmaster had resigned and fled the country. It was just the first in a series of shocks that would bring Austria to its knees.

In Hungary, the largest and most important province of the Austrian Empire, liberals forced Ferdinand I to grant Hungary near total autonomy or face war. In Italy, they went one step further and actually went to war. The news caused such unrest in Vienna that the Habsburgs fled the city.

But while most of the imperial family retreated to safety, Franz Josef did the opposite.

He went to Italy.

That summer, Franz Josef personally fought for Austria, turning himself into a soldier hero. This was in great contrast to Emperor Ferdinand, who quickly made himself into a villain.

That fall, Ferdinand sent the imperial army marching on Vienna. The breathtaking bloodshed that resulted allowed the Habsburgs to retake their capital, but it also left Ferdinand’s reputation in ruins. With Hungary now also at war with Austria, it was decided the useless emperor had to go.

In December, 1848, Franz Josef’s mom, the Archduchess Sophia, and an ultra-reactionary known as Prince Felix zu Schwarzenberg staged a palace coup. They forced Ferdinand to step down, replacing him with Franz Josef.

For the 18-year old boy, it must’ve been a dizzying moment. Just six months earlier, he’d been a soldier, fighting in Italy.

And now here he was, ruler of an empire that had self-destructed like a Humpty Dumpty made of fissile plutonium.

It was up to him to put that empire back together again.

Cracking Down

The arrival of Franz Josef on the throne was initially treated with optimism by his subjects. He was a fresh-faced teenager. Surely he had to be more progressive than the last guy?

Oh boy, were these 19th Century dudes in for a rude awakening. Franz Josef’s main priority as emperor was to end the war with Hungary. But he didn’t do this with negotiations.

Instead, he called in the Russians.

The Russian invasion both ensured that Hungary would stay within the Austrian Empire, and that the Hungarians would never trust Vienna again. It didn’t help that Franz Josef followed up Hungary’s defeat by having hundreds tried for sedition, driven into exile or executed. When an unemployed tailor tried to assassinate Franz Josef shortly after, it wasn’t the emperor who ordinary Hungarians expressed sympathy for, but his would-be assassin.

Still, the crackdown Franz Josef launched – coordinated from behind the scenes by Archduchess Sophie and Prince Schwarzenberg – did have the desired effect. Come the end of 1849, the fires of revolution across Europe had been reduced to smouldering embers. In France, the years of chaos had seen the Second Republic rise and then fall as Napoleon’s nephew, Napoleon III, seized power.

In the German Confederation, the revolutionaries had tried to unite all 39 states into a single thing called “Germany”, only to implode over the question of whether Austria or Prussia should be its leader.

But their efforts had at least brought one Prussian farmer into politics for the first time. Known as Otto von Bismarck, he and Franz Josef were destined to collide with enough force to reshape Europe. For now, though, no-one could tell just how the failed revolutions of 1848 were going to effect the future.

In Austria, Franz Josef set about consolidating his power. Egged on by Archduchess Sophie and Prince Schwarzenberg, he instituted a reign of neo-absolutism, characterized by an absolute lack of freedom of speech, a brutal secret police, and an invasion of organized religion into every aspect of citizens’ lives. Yet even at this frankly autocratic stage, the young emperor did find it in his heart to do some good.

Not long after taking power, he began dismantling the anti-Semitic laws that had kept Austria’s Jews confined to ghettoes and locked out of power. The destruction of these discriminatory statutes would eventually result in a flourishing of Jewish culture in Vienna.

But it’s doubtful Franz Josef was thinking much about all this in the early 1850s. That’s because 1853 was the year the emperor fell in love.

The Three Muses

In the story of Franz Josef’s life, there are three key figures. The first, obviously, was his mother, Archduchess Sophie, who got him onto the throne.

The second we’ve already met. Otto von Bismarck would shape the emperor’s middle years, whether Franz Josef liked it or not. The third was an unassuming Bavarian girl of fifteen called Elisabeth. But you likely know her by her nickname: Sisi.

A girl of jaw-dropping beauty with brown hair that came down to her ankles, Sisi was the sort of girl words like “radiant” are reserved for. Franz Josef first met her in 1853, when he traveled to Bavaria to propose to her older sister Helena.

But the moment the 23 year old emperor got his first look at Sisi, Helena metaphorically went out the window. Instead, Franz Josef proposed to the girl who’d just knocked him head over heels. The marriage between Franz Josef and Sisi was controversial for a number of reasons. Back in Vienna, Archduchess Sophie was enraged that her son had ditched safe and suitable Helena for some teenage tramp.

But it was also controversial in Bavaria, for the simple reason that the free-spirited Sisi didn’t want to marry this boring emperor any more than Sophie wanted her to. Nevertheless, Franz Josef and Sisi were married on April 24, 1854. While the emperor really would spend the rest of his life devoted to his new wife, it would not be a happy marriage.

But if you want to hear more about that, you’ll have to check out our Sisi video! Seriously, we’ve got a ton to get through today. While we are gonna hear more about Sisi, we don’t have time to do anything like justice to her story. However, we will mention one salient fact. Unlike her husband, the Hungarophile Sisi was very popular in Budapest.

In fact, it’s probably their marriage that did more than anything else to rehabilitate Franz Josef’s image. The rest of the 1850s passed in a blur of blunders and babies.

Blunders, because 1855 saw Franz Josef alienate both his ally Russia and the guys he wanted to be his new BFFs, Britain and France, by dithering over taking part in the Crimean War. And babies, because, well, Sisi had three of them. The first, Sophie, sadly died during a family visit to Hungary.

The second, Gisela, sadly – from Franz Josef’s perspective, at least – was a girl, and therefore worthless in the ridiculous world of 19th Century monarchs.

The third, though, was when the emperor got lucky. On April 21, 1558, Sisi gave birth to Crown Prince Rudolf. For Vienna, the arrival of the emperor’s new heir was cause for celebration. But while Franz Josef saw baby Rudolf as the guarantee his line would continue, he couldn’t have been aware of the darker truth. In just a few short decades, Crown Prince Rudolf was going to drive the Austrian court into deepest despair.

Enter Bismarck

For all the 86 long years of his life, Franz Josef would think of himself as a soldier first and an emperor second. So it’s ironic that the lowest point in his reign came thanks to his appalling military skill. A year after Crown Prince Rudolf was born, the Kingdom of Sardinia approached the flamboyant French dictator, Napoleon III, and suggested teaming up to drive Austria out of Italy.

To say the plot went to plan is to underestimate just how blindly Franz Josef blundered into the trap.

In response to Sardinian aggression, he personally rode out at the head of a vast army, only to watch in horror as the French appeared on the horizon, blowing raspberries and telling him his mother was a hamster and his father smelled of elderberries. The catastrophic loss of the 1859 war saw Austria’s Italian possessions almost wiped out.

Back home, Franz Josef was forced to call an assembly to write a new, more liberal constitution for the empire, lest the war’s outcome trigger another 1848. Gone would be the secret police, and the iron fist. In their place would be a new, cuddly Austria that didn’t hate its own subjects.

The trouble was, that was easier said than done.

Franz Josef was under tremendous pressure to give concessions to the Hungarians, but that would mean giving concessions to the Poles and Czechs too, which would in turn mean the Austrian right going into rebellion. It seemed all that nationalist feeling released by 1848 hadn’t gone away. Keeping it from tearing apart the empire would become a full time job.

But not everyone thought nationalism was a dangerous thing.

While Franz Josef tried to keep the tide of 1848 from rising again, up in Prussia, Otto von Bismarck was wily enough to know that the only way to deal with a wave is by riding it. The 39 German states wanted to unite? Fine, he’d help them do it. But it would be on his terms. And that meant ensuring Austria had no part to play in the coming Germany.

And so we come to the Schleswig-Holstein Question.

The details of what this actually was aren’t important. Just know that Schleswig-Holstein were a pair of states bordering Denmark, that they had a question, and that in 1864 Bismarck answered that question by punching Prussia’s iron fist right through the exam paper.

Importantly for our story, he convinced Franz Josef to help him do it.

For Franz Josef it appeared an easy win. The joint invasion allowed Austria to occupy Holstein and helped Vienna cosy up to Prussia. But Bismarck was playing the long game, the one known as “Strengthen Prussia at Austria’s Expense”.

As always, Bismarck played to win.

In January, 1866, Bismarck accused Austria of misrule in Holstein. Before long, the Iron Chancellor had whipped up tensions so skilfully that Franz Josef was forced to declare war.

The Seven Weeks War was as short and one-sided as its name suggests. Devoid of allies, Franz Josef could do nothing but watch as the highly trained Prussian Army steamrollered Austria. The defeat was so colossal that Prussia was able to force Austria out of the united Germany Bismarck was now actively building. In fact, the only reason the Seven Weeks War didn’t end with the Austrian Empire disintegrating is because Bismarck didn’t want to deal with a failing state on his doorstep.

But the damage had been done.

Austria was now weak, and Franz Josef’s reputation was in tatters. It would take a miracle to hold everything together after this.

A miracle… or a Compromise.

The Dual Monarchy

For the Hungarians, watching Austria get kicked around by Bismarck was the last straw. In late 1866, they basically told Vienna “look, we’re doing this independence thing.” In Vienna, panic descended. Some seriously counseled going to war with the Hungarians, consequences be damned.

But Franz Josef was through being a loser.

Ignoring his conservative advisors, he instead looked to his own wife, Sisi, a long time Hungarophile. With her support, and that of the court liberals who surrounded her, Franz Josef managed to get the hawks to abandon their war plans. In place of those plans, Vienna and Budapest negotiated a compromise. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 was a masterpiece of diplomatic footwork.

It split the Austrian Empire into two separate states: Austria (also called Cisleithania) and Hungary (also called Transleithania). They each had their own constitutions, their own systems of government, and their own monarchical structures. The key was that the Austrian Emperor and the Hungarian King would henceforth be the same person: Franz Josef. Joint ministries would also govern defense, foreign affairs, and finance. It was tiptoeing to the edges of independence, but not quite jumping. From this, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was born. For Franz Josef, this meant not just saving his empire from near-certain collapse, but being crowned King of Hungary in a lavish ceremony. Barely twenty years earlier, he’d been a warrior emperor, demanding the insurrectionist Hungarians be hanged for treason.

Now, here he was, sat alongside his Hungarophile wife, accepting the elevation of Hungary to partner in empire.

To his credit, Franz Josef accepted the world had changed. That December, 1867, he gave Austria the constitution it had been begging for since 1848. The new constitution laid out citizens’ fundamental rights. It established Austria’s first supreme court. It guaranteed the independence of the judiciary. The message was clear. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a different, more liberal beast to the Austrian Empire.

However, we shouldn’t kid ourselves that everything was cool. Although the new constitution placed great emphasis on rule via elected representatives, it maintained a veto that Franz Josef could use on any law. And he did, a lot. There was also still the national question.

When the Hungarians were elevated to equals, the Czechs were understandably all like “yeah, how come we don’t get any of that action?”. Over on the Hungarian side, things were even more vexed. While the “Austro” part of Austro-Hungary gave equal language rights to its minorities, the Hungarians were all about stuff being Hungarian.

That meant Romanians, Slovenes and Serbs all having to learn the language.

Still, the new empire was broadly a success. As Bismarck forged the German Empire from blood and iron, here was Austro-Hungary, rising instead from compromise. It was this iteration of the empire that would give the world the grandeur of Imperial Vienna; the secession movement of architecture; and the founding of psychoanalysis.

Unfortunately for Franz Josef, this golden age would also coincide with the darkest period of his life.

Goodbye, My Love

What’s remarkable with hindsight is that we can see the storm clouds gathering over both Austro-Hungary and Franz Josef even during the good times. On the empire side, there’s the occupation of Bosnia by Austro-Hungarian troops in 1878, that sparked Serbian fury. There’s also the treaty Franz Josef drew up with Otto von Bismarck in 1879. The one that stipulated the two states would fight on each other’s side in any European war.

But it was the personal side of things that likely hit Franz Josef hardest. It started in 1872, when his mother, Archduchess Sophie, finally passed away.

But it really took off in 1881, when young Crown Prince Rudolf – remember him? – finally married Princess Stephanie of Belgium. You’re probably thinking something like “well that doesn’t sound so tragic,” but sadly it was. Rudolf was an introverted, melancholy lad who didn’t want to marry this boring princess.

He took to having affairs, sliding deeper into unhappiness as he cut himself off from the outside world. It was in this state that he met Baroness Mary.

A 17-year old romantic, Mary was drawn to the gloomy, melancholic side of Rudolf. The two began an affair in which they guided one another ever further into heartache and depression. Finally, on January 30, 1889, the pair retreated to Rudolf’s hunting lodge. There they made a suicide pact before Rudolf shot Mary dead and turned the gun on himself.

And, just like that, Franz Josef’s only male heir was gone. The shock of the incident destroyed the imperial family. Never happy in Vienna, Sisi now fled the city, casting herself out into the world, wanting only to be reunited with her dead son. She got her wish just nine years later, when an anarchist stabbed her to death while she was out walking in Geneva.

With her death, Franz Josef was suddenly alone. By now a man in his late 60s, the emperor had reached a level of popularity with his subjects his younger self couldn’t have dreamed of.

In the imperial court, though, it was another story. With Rudolf gone, Franz Josef had been forced to make his nephew, Franz Ferdinand, his heir.

This was a problem, as Franz Ferdinand was pretty much the most unpopular man in Austria. Everyone who met him invariably wound up hating him. He was pompous, stuffy, awkward, angry, and only happy when he was out hunting. Yet, there’s an argument to be made that Franz Josef couldn’t have picked a better heir.

Franz Ferdinand was a dick. But he was also shrewd. He could see that the empire’s future lay in more federalism. That he could shore up support by elevating the Czechs and Serbians to joint equals with the Austrians and Hungarians.

There’s even a school of thought that, had Franz Josef been assassinated instead of Sisi, and Franz Ferdinand taken his place, there might even still be an Austro-Hungary today. But that’s not what happened. For all his bright ideas, Franz Ferdinand would not go down in history as the man who saved the empire.

Rather, he would go down in history as the man whose death killed millions.

The End of it All

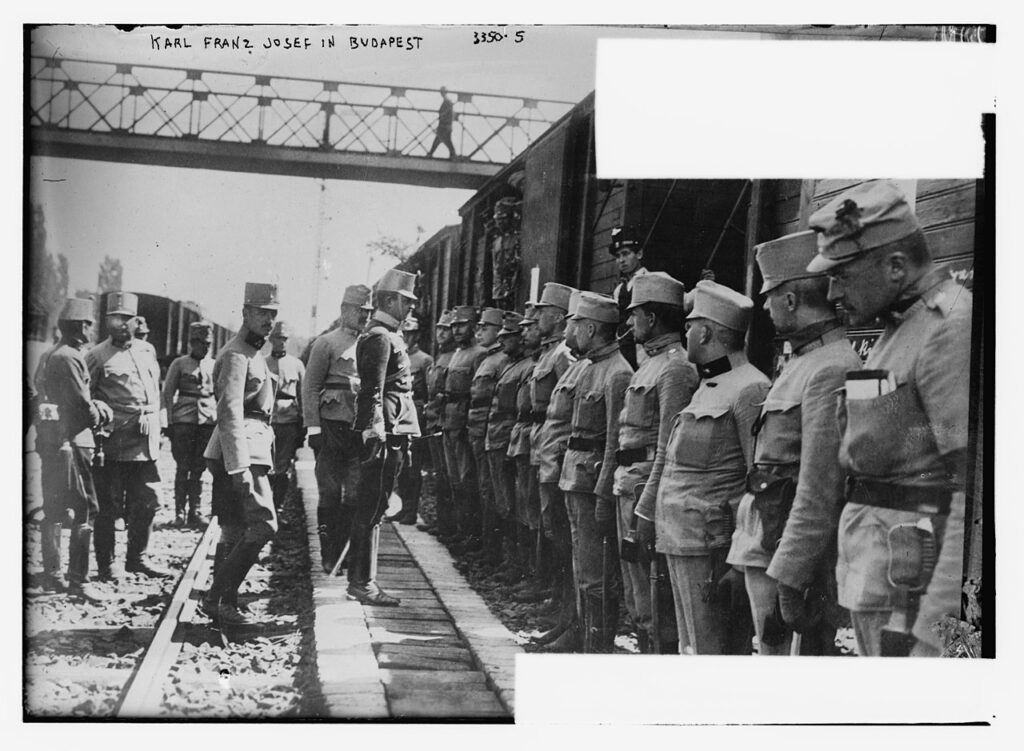

By the dawn of the 20th Century, decades of heartbreak had taken their toll on Franz Josef. The emperor had withdrawn from politics, settling into his role as a figurehead of empire.

This would’ve been great if he actually was a figurehead. But he was an integral part of the system. Without Franz Josef’s input, the empire began a period of listless drifting known as Fortwusteln.

While culture continued to thrive in Vienna, the only thing of significance to really happen before the 1910s was when Austria annexed Bosnia in 1908, kicking off a crisis that nearly led to war. But while war was avoided in 1908, it wouldn’t be kept at bay for much longer.

On June 28, 1914, the empire’s heir, Franz Ferdinand, was visiting the newly-annexed province of Bosnia when a Bosnian-Serb terrorist shot him dead. The assassination sent shockwaves through Vienna. When evidence emerged that the Serbian intelligence services may have had a black hand in the killing, Franz Josef was forced to act. At the advice of the hawks in his court, the emperor drew up an ultimatum to Serbia that was effectively impossible to follow.

In response, Russia and France gleefully announced they would defend Serbian honor from this Austrian aggression. Which made Germany declare they’d defend Austrian honor. Which made Britain…

Well, you know the rest.

On July 28, 1914, Franz Josef signed the decree declaring war on Serbia. It would be the last major act he’d undertake as emperor. The declaration effectively started WWI, not that we should blame something so complex on poor old Franz Josef. At hundreds of points, somebody in Serbia, or Russia, or France, or Germany, or Britain could’ve blinked and averted catastrophe.

That they didn’t was a failing that went beyond one doddering old emperor. Although Franz Josef didn’t live to see it, the declaration would kill his beloved empire. In 1918, as the war drew to a close, the many nationalities of Austro-Hungary all made a break for it, shattering the empire for good.

But, by this point, Franz Josef was no longer around. On November 21, 1916, the elderly emperor had died of pneumonia, passing away in the same palace he’d been born in. His funeral procession on November 30 would be the last time his empire came together in unity. Even at the time, people felt it was the end of an era.

Two years later, it would all be gone.

From our vantage point of the 21st Century, we can see that Franz Josef was a flawed man. While he instituted reforms that turned the autocratic Austrian Empire into a powerhouse of culture, he only did so when his hand was forced. Equally, while he was a decent general, we can also see that he was hopeless when faced with a great strategic mind like that of Otto von Bismarck.

What do we mean, then, when we call him the Last Great Emperor? Well, there are different ways of defining great. For some, that means a person who is exceptional, someone like Napoleon.

But it can also mean someone who embodies a certain way of being. Franz Josef grew up in a world where emperors were father figures who looked after their subjects, neither the tyrants of yesterday nor the mere symbols of today.

By sheer dint of his long life, he became one of the very last of this type, a widely beloved figure who managed to unite multiple nationalities under his rule, even as he still took an active hand in empire. He may have been unimaginative, obsessed with duty, and too slow to recognize the need for change.

But Franz Josef was likely the last great emperor Europe will ever see. With his death, an entire age was lost forever.

Sources

Britannica biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Joseph

Habsburg biography: https://www.habsburger.net/en/chapter/franz-joseph-childhood-and-upbringing

1848 in Austria (plus some general Austrian history): https://www.britannica.com/place/Austria/Revolution-and-counterrevolution-1848-59

The Jewish view of Franz-Josef: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/franz-joseph-i

We should also link to these, guys:

Sisi Biographics:

Otto von Bismarck Biographics:

Metternich Biographics: