He was a man who was impossible to ignore – a huge flamboyant character with a cigar and a $50,000 pinkie ring. Although he weighed over 250 pounds, he could, when the occasion demanded it, move with lethal speed and force. His jowly smile contrasted with the two scars that streaked across his left cheek.

Then there was his clothing. His wardrobe was nothing short of outrageous – custom tailored purple suits, pearl-gray fedoras and diamond encrusted stickpins. He loved attention, wanting people to adore him, even as he ruthlessly dispatched those who he had no use for.

His name was Al Capone, and he has become the symbol of American greed and corruption in the 1920s and ‘30’s. When he died, on January 25th, 1947, the New York Times called him ‘the symbol of a shameful era, the monstrous symptom of a disease which was eating into the conscience of America”.

But the paper went on to say . . .

Capone was incredible, the creation of an evil dream.

Yet, almost everything that the public thought they knew about him, and that most of us think we know today, is false – the product of decades of glorification and myth making. In today’s Biographix video we peel back the layers to discover the real Al Capone.

“I am like any other man. All I do is supply a demand.”

Gabrielle and Teresa Capone made the big move from Sicily to New York in 1894. They ended up in a four room flat on Park Avenue, adjacent to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The young couple had two sons in tow, the youngest just a few months old. A third boy followed shortly after their arrival.

A barber by trade, Gabrielle was looking for a new life in America. What he found was found a city in which immigrants were viewed as lower citizens. Italians were especially vilified by Americans who blamed for the spiraling crime rate that New York was experiencing. Yet, the Capones were a hardworking family, law abiding and trying to fit into their new society.

When their fourth son, Alphonse, was born in 1899, the family had settled into a decent, hard existence. Life around the Brooklyn Naval Yard was rough and tumble. By the age of 10, young Al Capone had begun to exhibit the toughness and rashness that he carried into his adult life.

From the start Al emerged as a natural leader. At age 14 he formed the Navy Street Gang in order to protect Italian women from harassment from their Irish neighbors. By now he’d been expelled from school for punching a female teacher in the face – hey, she hit him first!

Just prior to the outbreak of World War One, the Capone’s moved out of the Italian ghetto. Gabrielle’s head down and get on with it attitude was paying off and Al now found himself in an upwardly mobile middle class community. Still, further up the hill was where the really well off people lived. This area was strictly off limits to the likes of the Capones. The teenage Al looked upon this area with envious eyes. This was where the Rockefellers lived and the feisty teen saw no reason why he couldn’t live the Rockefeller way – he just had to find the means of getting there.

By the age of 19, Al had become a local tough who knew how to use a gun and a knife. He was a big, brutish brawler who could knock a man to the ground with a single punch. He’d also found himself a family. On December 30, 1918, he married Mae Coughlin, who was two years older than him. Three weeks previously, Mae had given birth to their son, Albert.

Family life encouraged Capone to get onto the straight and narrow. Intent on turning to a respectful life worthy of his wife and child, he moved the family out of the neighborhood and away from the bad influences. They shifted to Baltimore and Al took a job as a bookkeeper. Ironically, this ‘straight’ job would come in handy down the track when he was juggling millions of dollars earned from bootleg liquor.

That could have been the end of the story for Alphonse and Mae Capone. They could have settled into a life of uneventful respectability in Baltimore, maybe even working their way up the social ladder to gain some community status.

But that wasn’t to be.

With the sudden death of his father of a heart attack, Al’s flirtation with respectability was over. He returned for the funeral and soon found that the family were now looking to him for guidance and financial support. That would require more money than he was earning as a bookkeeper in Baltimore.

Meanwhile, the local gang that Al had pulled away from, an outgrowth from the Manhattan based Five Points Gang, was at a cross-roads. Six months earlier, a mafia bigwig in Chicago named Big Jim Colosimo had been shot dead. The leader of the gang that Capone had pulled away from, Johnny Torrio, was intent on stepping into the vacuum created by Big Jim’s demise. He invited Capone to join him as his right hand man.

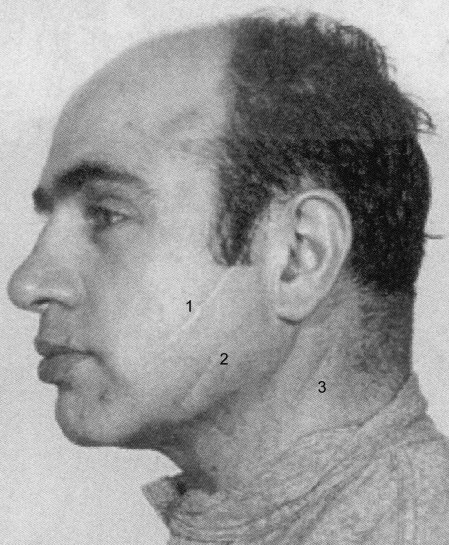

Torrio had been grooming Capone for the last couple of years. He’d given him a job as a collector to ensure extortion payments were paid. Al soon graduated to become the main bouncer and bartender at The Harvard Inn on Coney Island. One night, Al told a female patron that she had a nice rear end. The girl’s brother didn’t take kindly to the remark and, in an instant, he’d carved up Capone’s face with a bottle opener. For the rest of his life, Al would carry dual stripes down his cheek, giving rise to the name ‘Scarface.’

While he’d been in Baltimore rumors had circulated that Al had been involved in a couple of murders, one a prostitute who was suspected of withholding pimp money and the other a friend who had reneged on a gambling debt. All of this was bringing unwanted police attention to the gang. Shortly after his father’s funeral, Capone was called to a meeting with Lucky Luciano, a key member of the gang.

‘What’s going on?’ Al asked nervously.

‘I’ll tell you what’s going on.’ Luciano replied. You gotta’ get the hell outta’ town and don’t bother to pack.

Luciano then handed Al an envelope containing $2,000 and directed him to go straight to Grand Central Station and head for Chicago. Now he had no choice – he had to accept Johnny Torrio’s offer.

Capone Arrives in Chicago

Capone arrived in Chicago in 1921, ready, willing and eager to learn the ropes. He left his wife and baby behind in Brooklyn with instructions to follow once he’d established their new life.

The challenge for Johnny Torrio, the new boss of the Chicago outfit, was to transform his brutish understudy from relying on his fists to using his brains to succeed in the rackets. He put Capone in the position of head bouncer and bartender at the Four Deuces, a four storey building which served as Torrio’s general offices, while also housing a saloon and cafe. The top floor was a brothel. Al regularly partook of the top floor services, with his sexual proclivities resulting in a life long battle with syphilis.

This was no place for the weak of heart. Countless unsolved murders took place there, with Al playing a leading hand in dispatching those who Torrio wanted eliminated. In fact, Al did so well that, within the year, he was made a quarter partner, sharing in the $100,000 in annual profits.

Torrio taught Capone how to portray an air of respectability even as he delved deeper and deeper into the underworld. As a cover, Al opened a secondhand furniture store next door. He carried business cards announcing his occupation as a furniture dealer.

Be careful who you call your friends. I’d rather have four quarters than one hundred pennies.

As Chicago authorities began to crack down on organized crime, Torrio spread his business interests into the suburbs. In the suburbs, local police and politicians could be more easily controlled. In fact, it was Torrio’s expansion beyond Chicago that was the key to the development of the empire that Capone would inherit. By the time Capone arrived in the Windy City, Torrio had already set up vice, gambling and prostitution operations in the nearby town of Burnham. Then, with the election of crime busting Chicago mayor William E. Devine in October 1923, the entire base of the operation was moved to the western suburb of Cicero.

The plan was to make Cicero a wide open town where the gang could peddle booze and accommodate gamblers at will. To do so, Torrio agreed to shut down his brothels in Cicero so long as he had free rein with the other two arms of his business. By cutting the police and politicians in on the profits, Johnny soon got the free hand that he wanted. Within six months of moving in, the outfit owned the town of Cicero lock, stock and barrel.

By January of 1924, Torrio felt so confident in his position that he embarked on a trip back to the old country, where he planned to set his mother up in a fine estate in Venice. In his absence, Al would be in charge.

Al’s first challenge was to make sure that the officials who he had in his back pocket stayed in office. The local elections were to be held in April and Capone was prepared to go to any lengths to keep the incumbents in office. He brought his two older brothers, Ralph and Frank, over from New York to provide extra muscle. The brothers thought nothing of destroying ballots from the opposition’s stronghold and replacing them with votes for their candidates. Community officials went along with whatever the Capones did to keep them in office, with the police, the sheriff, even the state’s attorney, either going along with them or deciding that it was futile to try to oppose them.

On the day of the election in Cicero, Torrio-Capone gangsters used guns and fists to intimidate voters, escorted them to the ballot box and watched them drop them into the box for the incumbent mayor. Honest poll watchers and election officials were held captive until after the ballot closed. Some uncooperative citizens were even shot and killed.

Honest citizens were outraged, with some of them calling upon Chicago judge Edmund J. Jarecki to do something about the Cicero gang. Jarecki deputized 70 Chicago cops, who went into Cicero in plain clothes and unmarked black sedans. They soon spotted Frank Capone on the street, gunning him down and then riddling his body with bullets.

When Al heard about his brother’s slaying, all of the sophistication that Torrio had imbued him with over the last year was ripped away. His savage bestiality was unleashed as he vowed to take revenge. It took all of Torrio’s persuasive skill to keep him in check.

But Torrio was not able to keep Capone out of the spotlight. Staying in the background had, in Al’s mind, cost the life of his brother. Torrio continued to preach non-violence, only resorting to brute force when all else failed. But the name of Al Capone was synonymous with violence. Try as he might to follow his leader’s advice, Capone was plagued by mayhem and a temper that he found difficult to control. Al’s base nature was combative rather than conciliatory, and it resulted in an awful lot of bloodshed in the years to come.

Al’s pent up emotions over the death of his brother Frank were given expression on the evening of May 8, 1924. His partner in a prostitution ring, Jack Guzik, had been roughed up by an Irish thug named Joe Howard for refusing him a loan. When Guzik informed Al about it, Capone immediately tracked down Howard in a bar and demanded to know what had happened. Howard took one look at Capone then, calling him a ‘dago pimp’, told him to get lost.

At that Al saw red.

He pulled out his pistol and shot Howard in the face in front of dozens of witnesses.

The law never convicted Al for this brazen murder, but the press did. The original story identified him as Al Brown, but, when it was picked up by other papers, it was corrected to Alphonse Capone.

It was the beginning of his public persona.

In January of 1925, Johhny Torrio was ambushed by rival gang members. He came within an inch of losing his life, surviving only to have a 9-month prison term slapped on him for operating an illegal brewery. While inside, he decided that he’d had enough of the Chicago madness. By the end of that year he’d completely handed the reins over to Capone and disappeared.

Capone Takes Over Chicago

Capone inherited a goldmine from Johnny Torrio that was fueled by a highly organized operation that operated largely behind the scenes. In fact, the duplicity was so complete that 99% of the citizens of Cicero never even saw a gangster. Rather, the mob used the government to control the area with noncompliant merchants being plagued with higher taxes and loss of parking in front of their stores. They quickly got the message and got in line.

Now, Capone set his sights on the north side of Chicago. To make headway, he had to first subjugate the deadliest gang Chicago has ever known – the Gennas, who operated openly, with ample police protection. The Gennas had also been major suppliers of alcohol to the Torrio-Capone outfit and Capone had even supported them in their battles with other gangs. But, after crushing the rival O’Banion gang, the Gennas decided to take over the Capone empire.

It would prove to be their undoing.

Some call it bootlegging. Some call it racketeering. I call it a business.

The Gennas selected a couple of Sicilians to assassinate Capone. However, recognizing Capone’s power and fearful that such an attempt would lead to their own demise, the Sicilian duo informed Capone of the Gennas’ intentions. Al convinced them to turn on the Gennas and in short order they had killed three of the Genna brothers. The remaining three brothers fled to Sicily.

With the Gennas out of the way, Capone now had to deal with the survivors of the O’Banion gang, who had raided Capone’s headquarters a number of times. On one occasion, using eight touring cars, they first shot blanks to lure people outside, then followed with live ammunition, hoping to kill Capone on the spot. The ruse didn’t work. Though over 1,000 rounds were fired, miraculously, no one was killed.

Al was convinced that the brains behind this attempted hit was Hymie Weiss, leader of the O’Banion gang and he immiediately ordered the death of Weiss. The hit-men set themselves up across from Weiss’ flower shop and waited . . . and waited. After a week, they finally spotted Weiss walking towards his shop, killing him and three of his bodyguards.

The killers, disguised as policemen, entered Moran’s warehouse and caught the seven victims off guard.

Stepping into the vacuum created with the killing of Hymie Weiss was Bugs Moran, who was as eager to get rid of Capone as Weiss had been. Moran had plenty of guts but little common sense. He publicly denounced Capone, especially for pedaling bad women and bad alcohol. Constantly on the attack, Moran’s troops launched a number of forays against Capone’s businesses.

By February of 1929, Capone had had enough. He ordered a massive hit on Moran to take place on St. Valentine’s Day. The killers, disguised as policemen, entered Moran’s warehouse and caught the seven victims off guard. Facing the victims against the wall as if to frisk them before arrest, the hit men mowed them down with a barrage of machine gun fire.

Moran was not among them, but this attack was enough to scare him off.

Having eliminated all opposition on the north side of Chicago, Capone now focused on the south. After a number of killings, his rivals sued for peace, agreeing to give Al a large slice of their operation.

King of Chicago Dethroned

By March of 1929, Al Capone was the undisputed king of Chicago, being portrayed to the public as the ultimate gangster. Yet, at the same time, he was being read the riot act by his peers.

For years, the leaders of organized crime had been holding annual meetings to discuss matters of mutual concern. Now the matter of mutual concern was what to do about Al Capone. Al had attracted a tremendous amount of unwanted attention with the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. He was bringing too much unwanted attention s the ‘king’ of Chicago and the time had arrived for him to be neutralized. The commission decreed that Joseph Aiello, an old enemy of Capone, would be put in place in Chicago to keep Al in check. Capone would also have to cede his gambling operations to the commission.

In this life all that I have is my word and my balls and I do not break them for nobody.

Capone was privately outraged that the commission was muzzling him in this way. But he was also smart enough to know that if he protested, he’d be quickly eliminated. He decided to take the advice of the commission and lie low for a while. And what better way to safely lie low than from inside a jail cell.

Within 16 hours of coming out of the commission meeting, Capone had been arrested for carrying a concealed weapon. Capone entrusted his size 111/2 diamond pinkie ring to his attorney with instructions to give it to his brother Ralph, who would become acting head until he returned.

He then began a 12-month jail term.

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/01/16/01163e38-849d-415b-ab03-3c80e56c8e29/capones_criminal_record_in_1932.jpg)

When he emerged from his prison cell in March, 1930 Capone discovered that the climate had changed. He had been listed as ‘Public Enemy #1’ by the FBI. The Federal government now considered him a menace to society and was prepared to do anything to put him behind bars for good. It was certain that Al was violating the Volstead Act by selling liquor, but was unable to prove it. Not even Elliot Ness and his Untouchables were able to stop Capone. Finally, the FBI decided that their best chance of putting Capone away was to convict him of tax evasion.

Capone was used to being cheered when he attended public events. But now that the government was bringing tax income evasion charges against him, crowds starting booing him. What’s worse, his formerly fail-proof methods of fixing the outcomes of trials were having no effect. Al did manage to bribe a number of jurors, but on the day of the trial, the judge switched the jury panel. From that moment on the jurors were sequestered and out of Al’s reach.

After presenting a damning case which highlighted a life of lavish spending yet virtually no tax payments, the prosecution concluded by reminding the jury that Capone was no Robin Hood. He spent wildly on himself and his cronies, doing nothing to help the poor and down and out. The jury found him guilty on three counts of tax evasion and, on October 24, 1931, he was sentenced to 11-years imprisonment. It was the harshest sentence ever handed down for tax evasion.

They can’t collect legal taxes from illegal money.

Capone thought that his gangland associates would now rally to his aid.

But he just didn’t get it.

Maybe his advancing syphilis had something to do with it. The reality was that he had been artfully shunted aside at the Atlantic City meeting in 1929. Now, two years later, his life out in the open for all to see and a felony conviction to his name, he was anathema to his gangland buddies.

They didn’t want to humiliate him.

So they ignored him.

Capone spent the last three years of his sentence at Alcatraz. By then syphilis had seriously eroded his mental faculties. By the time he died of cardiac arrest on January 25, 1947, doctors concluded that he had the mind of a 12-year-old child.