By Arnaldo Teodorani

Three centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, most of Western Europe was divided into small Kingdoms frequently at war with each other. They were threatened by the Umayyad Caliphate from the South, subject to the influence of the Byzantine Empire from the East and prone to the interference of the papacy. Cultural and economic development languished, marred by a lack of strategic vision and the loss of centuries’ worth of classical knowledge.

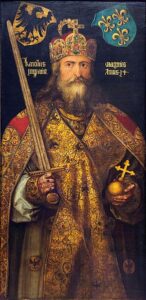

Then, in the 8th Century a new ruler emerged, a King who would bring about a cultural, political and military renaissance. But who could be as ruthless with his enemies, as he was enlightened in the administration of his Kingdom. Today’s protagonist was hailed as the Father of Modern Europe. He was celebrated in art, in literature … and even in heavy metal concept albums sung by Christopher Lee. His name was Charles the Great, better known as Charlemagne.

Rise to power

Much of Charlemagne’s life is documented by a biographer, Einhard, who was his contemporary. And he happened to be also his maths teacher when the King was already an adult. However, Einhard himself admits that little is known about his early years.

We do know that the boy Charles, later known as Charlemagne, was probably born in Aachen, modern-day Germany, in 742. He was the eldest son of King Pepin of the Franks and had a brother called Carloman. The name ‘Charles’ means ‘Free Man’. ‘Carloman’ means ‘Free Man-Man’. Pepin was known as ‘the short’, we may add another nickname ‘he who had little fantasy for names’.

King Pepin was the first of a new dynasty, the Carolingians, named after his own father, Charles Martel. Charles Martel was not a King, though, he was a Mayor of the Palace to the Kings of the Merovingian dynasty, which had ruled the region since the year 450.

The Merovingians had been losing power and influence for years, becoming merely figureheads, while the real power was wielded by the Mayor, a role similar to today’s Prime Minister – or Hand of the King if you like.

Pepin was bent on replacing the last of the Merovingians, Childeric III, as monarch and sole ruler. To do so, he needed legitimacy, and at that time the finest purveyor of legitimacy was the Pope. He addressed a letter to Pope Zachary in Rome asking

“Is it right that a powerless ruler should continue to bear the title of King?”

Zachary agreed immediately. He needed a powerful champion, as the Church in Rome was under a double threat. Politically, the Lombard Kingdom in Italy was increasingly hostile towards the Pope’s secular rule. Ideologically, the Byzantine Emperor wanted to impose a ban on representations of Christ in all Western European churches, as this was seen as idolatry.

Pepin was crowned King of the Franks in 751 and named both his sons as successors. He also defeated the Lombards, donating a large portion of their land to Zachary.

The Pope, in return, thanked Pepin by graciously and totally scamming him. Let me explain. Zachary produced a document known as the Donation of Constantine, drafted by the Roman Emperor himself, which stated that all Christian monarchs gave up their rule voluntarily to the papacy and the Pope then handed it back.

In other words: A King was such by the grace of the Pope, and the Pope had ultimate authority over his right to reign. Pepin accepted this stipulation. What he did not know, being poorly educated and illiterate, is that the document was a forgery, an instrument by which the papacy sought to control Christian kingdoms.

While his father ascended to the throne and dealt with Popes and Lombards, we can assume that Charles was busy training to become the warrior-king he would later become. We are going to relate only two specific episodes of his youth: in two occasions, at age 6, and then at age 15, he swore an oath to allegiance to the Papacy and Christendom. Charles would use his sword to protect and expand Christianity, an oath that would shape many of his military decisions.

In 768 Pepin died and the Frankish Kingdom was split among his two sons. At this time the Kingdom included most of modern day France, Belgium and some territories in Western Germany.

Charles and Carloman did not get along well, due to their radically different personalities. Charles always favoured direct action, while his brother was less impulsive. The first major disagreement came when the province of Aquitaine – south western France – rebelled in 769. Carloman was against a military intervention while Charles could not wait to march against the rebels … which he did, quickly defeating them and annexing a new province, Gascony, along the way.

The following year, 770, Charles was 28 and thought it was time to marry. His was a political choice: a Lombard princess, daughter of King Desiderius. The marriage was so unhappy and short-lived that we don’t even know the name of the girl! Charles in fact repudiated her the same year to marry a Swabian teenager, Hildegard.

Desiderius was furious. He approached Carloman proposing an alliance to topple that Playboy Charles – a civil war was on the horizon. But, very conveniently, Carloman died in 771, apparently of natural causes. The Frankish kingdom was now united under Charles’ rule.

The Warrior King

For the best time of his 56 years old reign, Charles was busy with military campaigns, crushing rebellions, securing borders and expanding his dominions. According to historian C.W. Hollister, these campaigns initially were not borne out of a clear vision:

“Charles led his armies on yearly campaigns as a matter of course. Only gradually did he develop a notion of Christian mission and a program of unifying and systematically expanding the Christian West”

We’ll first take a look at his wars against the Saxons, which he waged from 772 to 804.

Nowadays Saxony corresponds to a vast area of Northern Germany, bordering the Netherlands and Denmark. The Saxon people were split into several different tribes and had been in good terms with the Franks, which used their territory as a trade route with the Danes.

Things changed in 772 when a Saxon party raided and burned a church in the Frankish town of Deventer. It is not known why, but this was the perfect excuse for Charles to invade. The Saxons still held Pagan beliefs and worshiped the Norse pantheon of Gods, something Charles did not tolerate. It has been speculated that the Deventer raid may have been a false flag attack orchestrated by the Franks.

In retaliation Charles led his army into Saxony and destroyed the sacred tree Irminsul, a representation of the mythical Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life in Norse mythology. This was only the first of eighteen invasions, all marked by much burning, pillaging and slaughtering.

In 777 the Saxon tribes united behind the warrior-chief Widukind, a name which translates as ‘Child of the forest’. His resistance was brave and hard-fought, but had little chance to succeed against the Frankish armies. Widukind did succeed in convincing King Siegfried of Denmark to allow Saxon refugees into his kingdom.

Charles campaigning grew increasingly ruthless, perpetrating actions that nowadays would have him trialled at the Hague International Court of Justice. In 782 he ordered the murder of 4,500 Saxon prisoners: this was the Massacre of Verden, an atrocity condemned even by his contemporaries.

The Saxons continued fighting, preserving their autonomy and their religion. But Widukind realised this could not go on forever and allowed to be baptised in 785 as a gesture of peace. The rebel leader disappeared from historical records after this event, but his followers still did not yield.

Charles continued with his campaigns, even preventing refugees from escaping to Denmark in 798. After 32 years of war, Charles finally found a solution in 804: he ordered the mass deportation of more than 10,000 Saxons to Neustria – North Western France – while relocating a similar number of Franks into Saxony.

This forced displacement effectively ended the conflict and absorbed Saxony into Charles’ dominions. Now Charles’ territories bordered with Denmark and this did not please the Scandinavian kings. Siegfried of Denmark attacked Frisia (today’s Netherlands) almost immediately. Fortunately for the Frisians, the Dane died shortly afterwards and his successor sued for peace.

While waging a protracted conflict against the Saxons, Charles was able to conduct campaigns in other parts of Europe.

In 774, answering a plea from the Pope, he crossed the Alps and defeated the Lombards after besieging their capital Pavia. The Lombard kingdom was annexed by Charles, who now became the King of the Franks and the Lombards.

He then turned his attention to the Basques, who were threatening Gascony. The Basques were – and are – a tough bunch and defeated Charles at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778. But ultimately they were beaten, as were the Saracens in northern Spain.

The Franks and the Saracens, or Moors, continued fighting intermittently until 812. Charles was able to seize from the Moors Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearic Islands.

In Northern Spain, the Saracens were put in check by the foundation of the Spanish March – a fortified buffer zone extending from the Pyrenees to the Ebro river and Barcelona.

During the 780s Charles scored further victories in Germania and Italy. He expanded his kingdom southwards in 787, by conquering part of Southern Italy after the siege of Salerno. He also stretched eastwards by annexing Bavaria and Carinthia (modern Austria) in 788.

In 795 Charles attacked the powerful Empire of the Avars of Hungary. He had set his sights on them since the conquest of Lombardy, but had interrupted the campaign to deal with the Saxons. In the meanwhile, a civil war had weakened the Avars. Charles took advantage and by 796 he had conquered their fortified capital, known as ‘The Ring’, looting their enormous treasure. After a revolt in 799, the Avar were definitively crushed in 803.

Further expansion continued into eastern Europe: the Northern Balkans and the lands up to the rivers Oder and Danube all became dependent territories of the mighty Charlemagne.

The Carolingian War Machine

All these kingdoms and populations seemed to succumb incredibly easily to Charles’ armies, except for the Saxons. How did Charles achieve this? What were his winning strategies?

The Frankish army was organised around a core of heavy cavalry, an aristocratic warrior elite wearing chainmail and rounded helmets, armed with swords and lances. They were supported by infantry carrying polearms and shields, fighting in massed ranks.

Disappointingly for Hollywood, Charlemagne’s armies avoided large pitched battles, if possible. Surprisingly, when they were lured into battle, they performed poorly, such as Roncevaux. The Frankish established their superiority through well-prepared long-term campaigns instead, which harassed and worn down their opponents.

In fact, the value of Charles’ cavalry did not lay in spectacular charges against enemy formations. Rather Charles exploited its speed of deployment, the ability to harass enemies, burn villages, loot and pillage, before quickly moving to another theatre.

Charles was also a master of logistics: he usually planned his campaigns around Easter, the period in which plenty of fodder was available for the horses, making the most of the army’s greatest asset. His vassals were ordered to gather at least three months’ worth of food prior to a campaign, to ensure sustainability.

Unlike the custom of the time, the Frankish army did not simply raid enemy territories, and then left, as a means to enrich themselves. Charles made sure that new fortresses were built and garrisoned in the areas he invaded.

Another asset at Charles disposal was the sheer size of his army, numbering up to 35000 men. While relatively small numbers for late classical period standards, this was a juggernaut compared to the enemies of the Franks. This allowed Charles to split his army in two or more corps, and to perform pincer movements to outmanoeuvre their defences.

In short, Charlemagne’s dominance in logistics and strategy meant that he could afford to avoid the battlefield – but if he did engage in battle, and lost, he could still win the war.

What really made possible this military organisation was the administrative reforms which Charles implemented in his reign.

Carolingian renaissance

In order to administer such a large territory, Charles subdivided his kingdom into an inner core and outer ‘regna’. The core comprised the provinces of Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy, supervised directly by him and a system of envoys, the missatica system.

The outer ‘regna’ were divided into Counties, each ruled by a trusted Count, or Earl. In turn, they presided over a number of lesser vassals, each of whom was expected to train and equip himself for cavalry warfare. The counts could also rely on seven ‘scabini’ each, experts in law which ensured unity in the administration of justice.

Border counties were grouped into Marches ruled by Markgrafs, or Marquesses. They had the responsibility to maintain borderline fortifications and raise rapid reaction forces in case of an invasion. Larger territories characterised by a distinctive ethnic group were organised as Duchies. Charles also created two sub-kingdoms in Aquitaine and Italy, ruled by his sons Louis and Pepin respectively.

All the local rulers were summoned to attend an annual assembly, the Marchfield, in which they discussed political, judicial, military and religious matters.

Charles’ success as a ruler can be traced to his admiration for learning and education. His reign ushered in the era of the Carolingian Renaissance, characterised by a rebirth of scholarship, literature, art, and architecture.

Charlemagne’s conquests brought him into contact with the cultures of Moorish Spain, Anglo-Saxon England, and Lombard Italy, which greatly increased the institution of monastic schools and book copying centres.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in scholarship, promoting the liberal arts at the court, ordering that his children and grandchildren be well-educated, and even studying himself. He studied grammar, rhetoric, logic, astronomy, and arithmetic. Surprisingly, he was not able to write, and even his ability to read is put into question by historians.

What is not put into question, though, was the fact that Charles had created the largest single political entity in Western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire in 476. His Kingdom had unified wildly different territories and ethnicities. They had been unified by force, but had been kept together by his administrative skills, which included the creation of a single currency – the livre – and even a single writing system: the ‘Carolingian minuscule’ which established unified rules for language, script and grammar to ensure effective communication among every corner of the Kingdom.

A Kingdom which was about to formally become an Empire.

Holy Roman Emperor

In the year 800 Pope Leo III fell victim to a conspiracy led by Roman nobles. Accused of immorality and abuse of his office, he was forced to flee. Leo approached Charles asking for help to regain the Seat of Peter. Charles consulted with his advisor Alcuin, who recommended that he accepted the Pope’s plea for help.

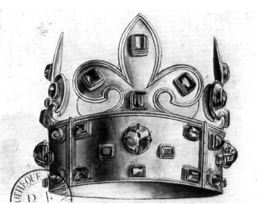

In December of the same year, Charles travelled to Rome to preside over Leo’s trial. Under his forceful influence, Leo’s name was cleared on the 23rd of the month. On Christmas Day, the pious Charles went to pray in front of St Peter’s tomb. When he emerged from the crypt, he was the target of a weird ambush. Leo III just stepped in front of him and placed over Charles’ head the Imperial Crown. A Crown which had been headless in the West for centuries.

With that simple gesture, Charlemagne had become the Holy Roman Emperor. In practical terms, this did not change anything with respect to his territorial dominions. Allegedly, Charlemagne, having been given the choice, would have refused the Crown. But, still, he did accept the added prestige.

As a clever man, he had understood that the coronation was a ruse concocted by Leo to regain some authority after his double humiliation: first, being ousted by the Romans; then, begging Charles for help. Leo was basically saying: I am still enough of a Pope to make this man an Emperor.

But Charles was no fool and knew very well that the next step would be for Leo to pull out the Donation of Constantine – remember? The forgery that had fooled his dad Pepin. Charlemagne did not fall for it and never accepted the Papacy’s political interference on his rule.

The Private Life of an Emperor

When dealing with the life of such a huge public figure it is easy to forget the private man behind the sceptre. Thankfully, Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard left an account of his private life.

When dealing with the life of such a huge public figure it is easy to forget the private man behind the sceptre. Thankfully, Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard left an account of his private life.

Charles was a tall and powerful man, standing at 6’3”, although he had a short neck and a pot belly. He regularly ate five meals a day, mainly consisting of grilled or roast meat. Apparently, he disliked doctors, after they recommended he switched to a lighter diet of stews.

I already mentioned his first two wives, the unnamed Lombard princess and Hildegard. This Swabian lady was always by his side, even during his campaigns and bore him four sons and five daughters, before dying aged only 26.

Let’s do some maths here. Although very testing, a healthy woman could give birth to a child every 12 months. Hildegard had nine children. Assuming that she was constantly pregnant, they married when she was 15.

If, however, she did have some respite between pregnancies … well, that would place her first pregnancy at an even younger age. But hey, different times, different habits.

Still, Charles could have kept his ‘sceptre’ in place once in a while.

Hildegard was buried in the Metz cathedral and her life became almost immediately fodder for legends, in which she was re-christened ‘Blanchefleur’ or White Flower.

Shortly after Hildegard’s death, the Charles who would not stop married Fastrada, daughter of an Austrasian count. According to Einhard she was

‘beautiful, ambitious and cruel’

which coincidentally is my Facebook status. Fastrada died in 794 and Charlemagne married a fourth time with Liutgard. Einhard described her as

‘ailing, good and devout’

which coincidentally is my Facebook status when my mum is online.

Liutgard barely managed to be Empress, as she died in the year 800. After her, Charles did not marry again, but he did have four mistresses, with whom he sired five more children.

Unlike many Monarchs before and after him, Charles had a very close bond with his children, spending plenty of time with them and taking a personal interest in their education. He made sure they studied to a proficient level the subjects of grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, geometry, astronomy and music.

After reaching the appropriate age, the sons were taught the real manly stuff, expected from Medieval princes: Hunting! Horse riding! Weapons training!

How about the daughters? Wool spinning. Nothing wrong with this, if it’s your calling. But if you are a daddy’s girl how frustrating can it be to watch your brothers go horse riding in the woods chasing wild animals with their pikes, while you are stuck at home spinning wool?

It is in truth reported that Charles’ daughters were all ‘daddy’s girls’ as in he loved them dearly and doted on them. But he never allowed them to marry – this is probably for political reasons. He already had to split his territories among four sons, he could not afford doing the same also for his potential son-in-laws.

Legacy

In the later years of his life, from 801 to 810, Charles faced arguably his most powerful foe, the Byzantine Empire. Charlemagne and Emperor Nicephorus I waged war on land and sea for control of Venetia and the Dalmatian coast. The war progressed well for the Franks, plus, in 809, Nicephorus was distracted by a new war with the Bulgars.

The Byzantines began negotiations with the Franks, and peace was agreed upon in which Charlemagne gave up most of the Dalmatian coast, in exchange for the Byzantine Emperor recognizing him as Emperor of the West.

In 813 Charlemagne appointed his son Louis the Pious as successor to the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne died in 814, at the age of 72, of natural causes.

Unfortunately, his death marked the beginning of the end for the Empire and the ruling system he had created. As pointed out by historian Prof Cantor, this was one of the cases in which the death of a single personality can cause the society around them to revert into a less developed state.

Charlemagne had created a solid infrastructure to ensure – at least in theory – the survival of the Empire. But he had sowed the seeds of the decline with his conduct in the Saxon wars.

In addition to perpetrating a series of atrocities, Charles’ conduct had enraged the Scandinavian kings and eliminated the Saxony buffer zone. The Danes waited for Charles’ death and then unleashed their Viking raids on France, which Louis the Pious was unable to effectively fight back.

The deterioration was further accelerated by the fact that the Empire was later split amongst Louis’ three sons, who had little interest to cooperate and to preserve Charles’ reforms. These three, and their descendants, were also under the influence and interference of the Papacy: unlike Charles, they had bought into the fraud that was the Donation of Constantine.

All in all, Charles material legacy did not last for more than two generations. However, he sowed the idea of the possibility of restoring a strong, unified Empire in Western Europe. He is also credited for being the initiator of the concept of a united Europe. Moreover, the kingdoms he created were the basis for current nation-states and his cultural reforms slowly dragged European people out of the Dark Ages.