At exactly 01:23am on April 26th, 1986, the world suffered its worst ever nuclear disaster. Outside the town of Pripyat in Ukraine, reactor number 4 at the local nuclear power plant quite literally blew its top, disgorging more radioactive material into the atmosphere than the Hiroshima and Nagasaki explosions combined. The resulting cloud of death blanketed half of Europe, led to the total evacuation of parts of north Ukraine and southern Belarus, and triggered a process that would end five years later with the complete collapse of the Soviet Union. Wow, I mean, there are disasters and then there are disasters, right?

But how much do most of us really know about history’s worst nuclear accident? Go on Wikipedia today, and the total number of deaths due to Chernobyl is listed at a paltry 31. The overall impression you get is of a disaster that’s notable, but not really in the league of something like 9/11. But impressions can be misleading. For those living in the USSR, Chernobyl was their 9/11. It affected workers from each republic in the Soviet Union, it permanently damaged trust in the government, and it left behind a deadly legacy that’s still being reckoned with to this day. This is the story of the town that blew up an empire.

The Paradise – Before the Explosion

It was a chilly February day in 1970 when the first brick of the new city was laid some 90km north of Kiev. Pripyat was officially under construction as the ninth of the USSR’s so-called “atomic towns,” places built solely for the families of those working at nuclear plants. In this case, that meant the Vladimir Lenin plant just 3km north, the plant you know as Chernobyl.

Life in Pripyat was far beyond the standards common in the Soviet Union at that time. The atomic towns were Moscow’s pride and joy. Those who lived in them could expect fully stocked shops, hospitals with actual equipment, and apartments that were the envy of people from Vilnius to Vladivostok. Even by these high standards, Pripyat was something else. Former residents still talk of local forests replete with natural beauty, and wax lyrical about visiting the river beachfront on sweltering summer days.

But from the get-go, there was a darker side to the new city. Over at the nuclear plant, authorities were quietly installing RBMK reactors, famous back then for their ability to be converted to nuclear weapons production at the drop of a hat. This useful ability also made them incredibly unstable, like driving a car without brakes. In only a short time, the reactor at Pripyat was gonna go screaming over a cliff-edge, taking its passengers with it.

On the eve of the disaster, though, everything appeared to be going, well, fine. Officially given city status in 1979, Pripyat had grown to a booming metropolis of 43,000 with an average age of 26. The young population meant no shortage of weddings and celebrations, and the town had become a hugely desirable posting for Soviet scientists.

Over at the Vladimir Lenin nuclear plant, four reactors were already up and running, with a fifth on the way. Former Pripyat residents later called those last days a kind of paradise. If that was the case, it was one that was about to be lost forever.

Paradise Lost – The Meltdown

One of the great ironies of the Chernobyl disaster is that it was caused, of all things, by a safety test.

On the night of April 25th, 1986, engineers untrained in nuclear physics decided to find out if the newly-built reactor number 4 could still operate its emergency water pumps in case of a power failure. So they disconnected it from all the failsafes, removed the control rods, and shut off the main power source.

The result was a surge that almost immediately ran out of control. In a panic, the engineers tried to reinsert all 200 control rods back into the reactor at once. This turned out to be a really, really bad idea.

The control rods had graphite tips that facilitated the unstable reactions already taking place. No sooner were they in than the reactor was hit with the mother of all explosions. The 1,200 ton cover was blasted into the air. Radioactive debris shot a kilometer into the night sky. Two workers in the control room were immediately killed.

Incredibly, survivors at the plant had no idea they’d just triggered a bona fide catastrophe. Their Geiger counters were geared up to detect low amounts of radiation exposure, the sort of amounts you might normally expect working at a nuclear plant. When the reactor spewed forth some of the highest levels of radiation ever seen, the Geiger counters, well they just stopped working.

Back in Pripyat, the local fire brigade mobilized. Nearly 30 men screamed up to the reactor in their trucks with no protective clothing on and poured water into the fire now raging. But the flames wouldn’t go out. Not only that, the men complained of a metallic taste on their tongues and a feeling of pins and needles in their faces. By the time they got home at the end of their shifts, a number of these first responders were already showing signs of acute radiation sickness.

Yet still no emergency was declared. When news reached Moscow at 5am, Soviet leader Gorbachev was infamously told the reactor was so safe it could be placed in the middle of Red Square.

Had Gorbachev taken them up on that offer, it would have been one heck of a sight. The ruins of reactor number 4 were at this point buried under 14 tons of highly radioactive rubble and burning at 3,000 degrees. It was also spewing radiation over north Ukraine and southern Belarus, plenty of which was already finding its way to Pripyat.

It had been a hot night that night. In Pripyat, many slept with their windows open, unaware that cancer-causing particles were now blowing into their bedrooms and settling on their exhausted bodies.

Yet when they woke up, it wasn’t to a warranted mass panic, but to an ordinary day. Yes, most of these people were nuclear plant workers, and most knew something had happened, but no-one knew the full extent of the disaster. As radiation fell in invisible, deadly clouds, children played outside in the streets, mothers went shopping, and men got ready for work.

The one discordant note was the sudden appearance of masked soldiers on the city streets. They stood in twos or threes, monitoring the crowds, not answering questions. It was the first sign the residents of Pripyat had of the nuclear tsunami about to engulf them all.

By the evening of April 26th, radiation levels in Pripyat were 600,000 times normal. The excellent documentary The Battle for Chernobyl – one of our main sources for this section –estimated that anyone exposed to those levels would have received a lethal dose within 4 days. Clearly, the Soviet authorities were going to have to react, fast.

At 2pm on April 27th, with the deadly fire still burning 3km away, 1,000 school buses were driven into Pripyat and parked on every street. Residents were called outside and told they had two hours to pack their belongings and prepare to be evacuated.

“There’s been an accident,” they said. “Don’t worry. You’ll be away for three days and we’ll sort this all out and then you can come right back. I mean, come on. We’re the Soviet authorities. Would we lie to you?”

So Pripyat’s residents prepared to leave paradise. They packed quickly, taking only what they could carry. Then all 43,000 were loaded onto the buses and driven away into the vast, flat emptiness of northern Ukraine. None of them would ever see their homes again.

The Liquidators – into the Inferno

You might be wondering what was going on in Moscow while this nuclear apocalypse unfolding. The answer is… nothing. Well, not much. The Kremlin did put a scientific delegation together to study the problem, but aside from that, Soviet authorities basically sat on their hands and, like a kid who’s farted at a party, tried not to let the rest of the big countries see them blushing.

Unfortunately, the radioactive fart unleashed by Chernobyl was just like a regular fart in one important respect: it stank. Not in the eggs and methane kind of way, but the stench of radiation, capable of being picked up by even the most basic equipment.

On April 28th, Swedish scientists monitoring their own nuclear power plants caught the first whiff of that silent, and very deadly, emission. With a figurative “eww!” they turned to all the other countries and said “guys! Guess what the USSR just did!” Although Moscow would try the geopolitical equivalent of “whoever smelt it dealt it” for the next 24 hours, the jig was up. On April 29th, the Kremlin came clean. From this point on, Chernobyl became a global emergency.

It was around this point the first responders arrived in Moscow’s Hospital Number 6, the one place in the whole of the Soviet Union geared up to treat acute radiation sickness. Of the 30 or so firemen who had responded that night, 28 would die in agony, their skin burned from their bones by an invisible enemy.

In the aftermath of the first responders’ deaths, an additional 130,000 people were evacuated from the towns and villages surrounding Pripyat. Yet even now, the Soviet authorities’ response remained woefully lax. In Kiev, a May Day parade was held with the blessing of the Communist Party, despite a change in wind direction meaning radioactive dust was now falling on the Ukrainian capital like a deadly rain.

One week after the initial blast, the meltdown was still underway. Although the fire had been put out with piles of sand, the reactor itself continued to burn. Meanwhile, dangerous readings were coming in from as far away as Greece and France.

It was against this worrying backdrop that the International Atomic Energy Agency made its most worrying announcement of all. With the reactor still melting downwards through the plant, Chernobyl was on the brink of a full-blown nuclear explosion.

Time for a quick explainer. The water the first – now dead – firemen had dumped into the reactor had pooled at the bottom. With the top of the destroyed reactor now plugged with sand to contain the fire, any molten radioactive goo that reached the water could trigger a chain reaction, which in turn could trigger a nuclear explosion.

We’re talking something in the region of three megatons. That’s 200 times the size of the bomb that flattened Hiroshima.

According to the utterly terrifying online tool Nuke Map, depending on the way the wind was blowing, this could have doused not just Minsk but also Vilnius all the way away in Lithuania in catastrophic levels of radiation. Were the wind blowing towards Kiev, 95km to the south, it could have turned the Ukrainian capital into a silent tomb.

It was at this point the Liquidators arrived.

In the last years of the USSR, the Liquidators were the equivalent of 9/11’s First Responders, the men and women who marched into the jaws of death, determined to do their duty.

![Radioactive steam plumes continued to be generated days after the initial explosion, as evidenced here on 3 May 1986 due to decay heat. The roof of the turbine hall is damaged (image centre). Roof of the adjacent reactor 3 (image lower left) shows minor fire damage. Igor Kostin took some of the clearer pictures of the roof of the buildings when he was physically present on the roof of reactor 3, in June of that year.[48]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/f/f6/Chernobyl_burning-aerial_view_of_core.jpg)

To read their story is to read a tale of heroism and suffering not seen since the Siege of Stalingrad. There are the 600 pilots who flew over the burning reactor, dropping lead on it to plug the broken top, who later suffered myriad health problems. There are the 125 firemen sent beneath the meltdown to drain the water out and stop the second explosion, most of whom got sick. And there are the 10,000 miners who came from Russia to create a concrete chamber beneath the reactor to stop it poisoning the groundwater, 2,500 of whom would die before the age of 40.

The circumstances they had to work under were appalling. There were men ordered to clear radioactive debris from the roof of the power plant, where radiation levels were so high they had to work in 40 second shifts or risk receiving a fatal dose. Miners who were forced to dig in 24 hour shifts without any protective clothing.

Then there are the stories of the clean up and decontamination of the Zone itself. The countryside surrounding Pripyat was so contaminated entire forests had to be bulldozed and buried. Villages were scrubbed from tip to toe. Perhaps most shockingly, special squads were given guns and sent out into the countryside to shoot all the dogs and cats, lest their radioactive fur now prove a danger to humans.

All told, it was one of the biggest clean up operations in human history, rivalling even Deepwater Horizon. It lasted six months, whereupon a 30 mile exclusion Zone was established around Pripyat. It remains to this day.

The final capstone was the sarcophagus. A concrete behemoth, it was placed over the reactor at the very end of 1986, just as the first snows began to fall. It sealed reactor number four off from the outside world completely, ensuring it would remain safe… at least for a time.

See, the sarcophagus was built in a hurry, and designed to only last 30 years. This wasn’t seen as a problem, as when 2016 finally rolled around, the Soviet authorities would clearly still be in charge in Ukraine and able to replace it with another one. I mean, it’s not like the entire USSR was gonna completely collapse in the next half decade or so… right?

The Aftermath – Paradise Regained?

On November 9, 1989, the world watched in awe as ordinary Germans toppled great chunks of the Berlin Wall while guards looked on. It was the start of the complete collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe, and the final dissolution of the USSR.

In Ukraine, mass protests against Moscow didn’t really break out until 1991. But when they did, the did so under Chernobyl’s deadly cloud.

In Kiev, protestors were photographed in gas masks and protective clothing, waving signs referencing the disaster. At a political level, the shutting out of Ukrainians from a disaster in their own backyard had immense consequences, the most-immediate of which was Kiev declaring independence on August 24 that year.

But the fallout from Chernobyl had effects far beyond Ukraine. The Economist has argued that the huge economic hit the USSR took from the disaster directly led to its collapse.

Back on the fringes of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, former residents of Pripyat watched these events with undoubtedly mixed feelings. Although their homes had been lost, the authorities had built them a new city called Slavutych to recreate their paradise. Many of them still worked at the old power plant. Remarkably, the other three reactors had been restarted at the end of 1986, danger be damned!

Yet new cities cannot make up for the toll Chernobyl took on its Liquidators. Across the USSR, hospitals had spent the last five years flooded with those who worked in the Zone.

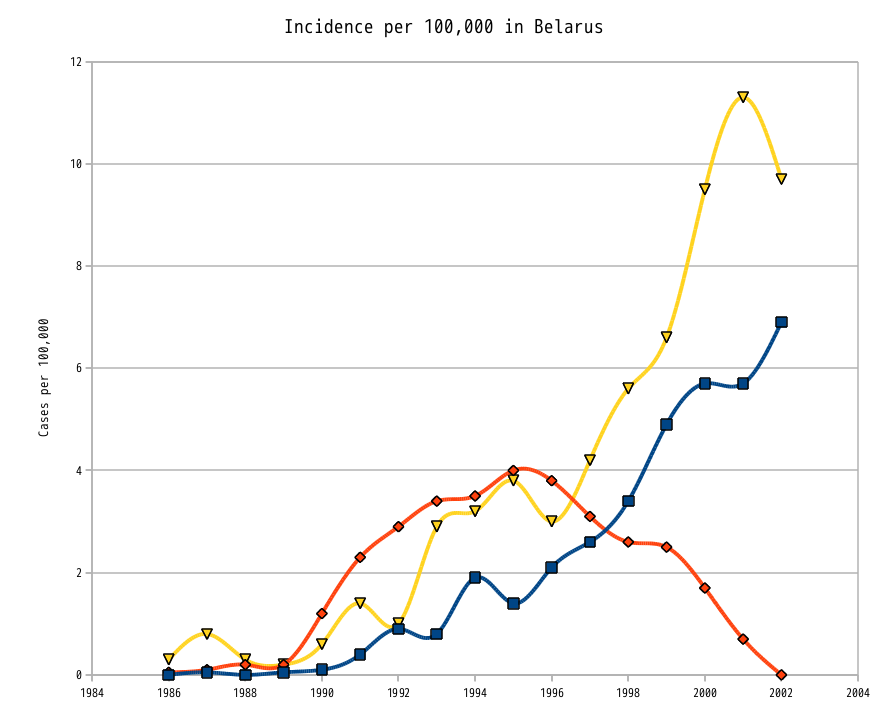

Today, it’s estimated that around a third of the surviving Liquidators are disabled in some way. In Belarus, which got more radiation than Ukraine, one study estimated that as many as 20 percent of the adolescent population suffer birth defects related to the accident.

As for the number of excess cancer deaths Chernobyl caused… we simply don’t know. The World Health Organization estimated on the 20th anniversary that it was around 4,000. But estimates vary wildly. One EU report put the number closer to 60,000.

Whatever the truth, the aftermath of Chernobyl has been a source of anger in Ukraine and Belarus ever since. When the plant’s other reactors were finally shut down following international pressure in 2001, few lamented their passing.

But the drama wasn’t over. In the late-1990s, it became clear that Ukraine was never going to be capable of rebuilding the sarcophagus when it finally failed. An international effort involving dozens of nations hastily scrambled to assess the danger. At which point it became clear that the sarcophagus was never going to make it to 2016.

Despite being built to last 30 years, the Soviet sarcophagus was already on the brink of collapse. The next ten years alone were spent shoring up the old structure to prevent yet another catastrophe. Then, in the mid-2000s, a new sarcophagus had to be built that would completely contain the old one.

At a staggering 35,000 tons, the new sarcophagus was a miracle of engineering. Built 300m away from reactor number 4 to limit radiation exposure, it took ten years to assemble, and then had to be rolled into place atop the old sarcophagus and completely sealed. It was taller than the Statue of Liberty, bigger than an Olympic stadium.

When it was finally sealed in November 2016, it had cost $1.5 billion. It is expected to last the next 100 years. During that time, robots inside will deconstruct the old sarcophagus, before finally dismantling and making the reactor itself safe. When the new sarcophagus finally reaches its end in 2116, it’s hoped humanity won’t need to build an even bigger one.

Today, the glistening new structure looks over a landscape that’s very different from the one reactor number 4 changed forever in 1986. The ex-paradise of Pripyat is no longer just empty, but crumbling away beneath an onslaught of nature. The once tame forests are now so devoid of people that the Exclusion Zone has become an accidental wildlife reserve, teeming with wolves, bears, beavers and lynx.

Not that people have completely vanished. Just a few short years ago, the Ukrainian government agreed to let a small number of Chernobyl evacuees back in. Around 200 now live within the Zone itself, dicing with death on a daily basis. You can even visit them. Chernobyl receives tens of thousands of tourists a year, drawn by the allure of Ukraine’s very own Pompeii.

As for the disaster itself, well, it thankfully remains the worst nuclear accident on record. Bad as the Fukushima meltdown in 2011 was, it didn’t even come close to Chernobyl’s 1986 eruption. Hopefully, neither accident will ever be exceeded.

Normally, this is the point where we’d wrap up our biography, say a few pithy things and let the credits roll. But Chernobyl’s story is still far from over.

It’s estimated that the Zone will remain uninhabitable to humans for another 24,000 years, a stretch of time almost beyond comprehension. It was only four and a half thousand years ago that the first pyramids were built in Egypt. Try to imagine, just for a moment, how different life was back then; how impossible it would have been for your average slave to close his eyes and imagine our world, to imagine spaceflight, penicillin, the internet. Now multiply that feeling by a factor of six. You now have some idea of the scale of time left until Chernobyl’s effects at last stop being felt.

Our story today may be over. But the tale of Chernobyl is only just getting started.

(Ends)

Sources:

Battle of Chernobyl: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IjOJlHULsaM

Nukemap: http://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/

https://news.vice.com/en_us/article/mbnnen/chernobyl-anniversary-nuclear-power-what-we-can-learn

https://www.economist.com/europe/2016/04/26/a-nuclear-disaster-that-brought-down-an-empire

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/07/chernobyl-30-years-residents-life-ghost-city-pripyat

http://www.who.int/ionizing_radiation/chernobyl/backgrounder/en/

https://www.businessinsider.com/birth-defects-related-to-chernobyl-2016-4

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nuclear-disaster-at-chernobyl