Victorian era Britain was a time of massive change. From sweeping imperialist expansion abroad to political and social reform at home, to the rise of mysticism, spiritualism, and romanticism, the nation was growing and, in many ways, thriving. For some, cities were becoming bustling, prosperous hubs of industry, but for the less fortunate, they also became cesspools of disease, darkness, and misery. It was an era of invention and advancement, and Britain’s citizens learned about it through the newspaper.

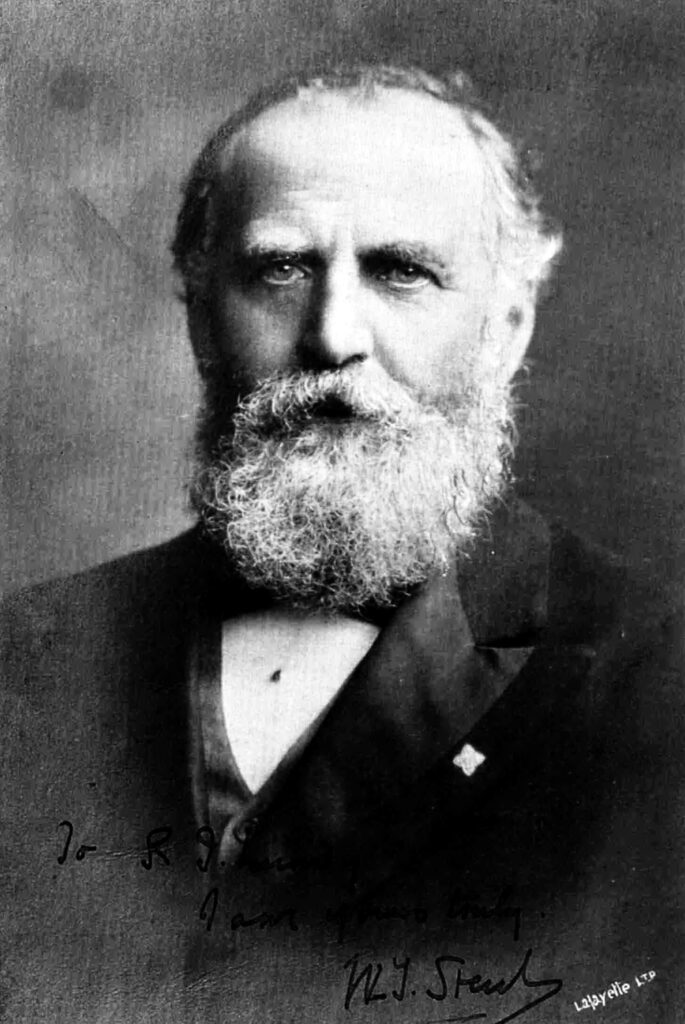

Before the modern era of journalism, there was once a time when the newspaper was simply for reporting the news. However, a young editor named WT Stead saw the potential for it to be something more — at one point, he described his vision to a friend as “a glorious opportunity of attacking the devil.”

And he did. There were plenty of devils out there, rearing their ugly heads during this time of all-encompassing change. Not only did he attack them, but people listened, and he proved that one person really can be the voice that changes history. This is Stead’s story.

A world shaped by the newspaper

Today’s world is connected in ways the average Victorian-era citizen could never have believed. News travels fast, they say, and today, that’s certainly true. It was quite a bit less true in the 19th century, so when newspapers became widely accessible in the mid-1800s, it quickly shaped the daily operation of entire cities.

Typically, newspapers were the only way people would hear about wars in far-away lands or the goings-on of their own governments. That made them powerful, and many built massive and ornate buildings that towered over the worlds they reported on. Since not everyone could afford to buy their own paper, public social clubs were formed and reading rooms were built, where hundreds of members could get together to share papers, read the news, and discuss. Others headed to the pubs, where landlords kept papers on hand and sometimes paid speakers to perform the news to raucous applause. There were more newspapers in public libraries than there were books, newsagents popped up everywhere, and newsboys hawked the latest edition with the help of signs proclaiming the day’s headlines. Suddenly, everyone was learning about the world, and they only wanted more.

William Thomas Stead was brought into that rapidly changing world on July 5, 1849. Born a minister’s son, he could read both Latin and English by the time he was five years old, and it would be his words that would not only shape his own life, but go on to change the world he lived in.

Even though it had originally been assumed that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a minister, that’s not what happened at all. After finishing his schooling, he ended up working as a clerk in a merchant’s office in Newcastle. While he was there, he was a regular contributor to a newspaper called the Northern Echo. The editor, John Copleston, saw something valuable in him and mentored him for a surprisingly short time. The paper opened in 1870, Stead got his foot in the door, and in 1871, the owner of the paper offered him his mentor’s job. At the time, Stead had never even stepped into the paper’s offices.

Stead hesitated, as he was loathe to take the job of a man who had been such an inspirational teacher and mentor to him. But when Copleston left voluntarily, he rose to the challenge, becoming the country’s youngest newspaper editor. It was a huge task, and to Stead, it was a chance to make a monumental contribution to society. He wrote, “I felt the sacredness of the power placed in my hands, to be used on behalf of the poor, the outcast, and the oppressed.”

And that’s exactly what he did. His goal was to create a newspaper that was just as entertaining as it was informative, one that would reach the masses and spur them to action. He started out in the most shocking way possible, with a topic he’d revisit later: prostitution. He called it “the ghastliest curse which haunts civilised society,” and at the time he was splashing it across the front page, it was such a taboo subject that talking about it was just as illicit as partaking in it. Stead’s condemnation of prostitution wasn’t quite universal, though — at the same time he condemned the wealthy echelons of society for funding brothels, he acknowledged that, for many, it was the only way they could put food on the table.

Stead’s preaching from the pulpit and his almost sermon-like articles set the tone for the Northern Echo and for the rest of his career. He condemned entire nations for their politics and their human rights abuses, and he waxed philosophical on why the death penalty was a necessary evil. That was a viewpoint that was a bit problematic, considering the paper was funded by Quakers, a religious group who believed there is a bit of God in everyone, and that all life is valuable. It wasn’t long before Stead grew too big for the Northern Echo, and headed to London to take up with The Pall Mall Gazette.

New Journalism

Stead continued his fire-and-brimstone flavor of journalism when he got to London, but it wasn’t particularly popular. Some of his contemporaries hated him as much as he hated London, and no one made a secret of it. At the same time Stead called the bustling metropolis “the grave of all earnestness”, his paper was nicknamed the “Dunghill Gazette” by poet Algernon Swinburne. Novelist Mathew Arnold was more direct, calling Stead’s sensationalist style “feather-brained”.

But as much hate as he got, he also got results. In 1883, the clergyman Andrew Mearns wrote a pamphlet called “The Bitter Cry of Outcast London”. It detailed the plight of the countless souls living in the slums of the city, and it was dire stuff. He wrote:

“Few who will read these pages will have any conception of what these pestilential human rookeries are, where tens of thousands are crowded together amidst horrors which call to mind what we have heard of the middle passage of the slave ship. To get to them you have to penetrate courts reeking with poisonous and malodorous gases arising from accumulations of sewage and refuse scattered in all directions and often flowing beneath your feet; courts, many of them which the sun never penetrates, which are never visited by a breath of fresh air, and which rarely know the virtues of a drop of cleansing water.”

If it wasn’t for Stead, the pamphlet might have gone unnoticed. But the journalist picked it up and ran with it, using The Pall Mall Gazette as a megaphone for Mearns’ monologue. Consequently, the paper increased its reputation for sensationalism and scandalous stories, as its readers were outraged at the lurid tales about what missionaries would find in the slums of London. The paper spoke of dozens of people, huddled together in the dirt and squalor, of children poisoned by the foul stench, of child corpses and vermin abandoned to rot the darkness.

The outrage of these freshsly realized details didn’t just disappear. Mearns’ words and Stead’s relentless promotion of the pamphlet resulted in new housing legislation and the organization of missions throughout London, whose only goal was to alleviate some of the suffering and misery described in the macabre tales.

The next year, Stead picked up another cause: the Navy. Calling for an end to party squabbles in the interest of national security, he appealed to the government to make sure its fighting fleet was, indeed, capable of fighting. The result was the government making a £3.5 million investment into upgrading its fleet, a staggering amount for the time. Clearly, readers were listening.

The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon

Stead’s tour de force came in 1885, published under the sensationalized headline “The Maiden Tribute of Babylon.” This is when he returned to a subject that he had condemned earlier — prostitution. This time, he was kicking the door wide open on one of the darkest areas of London’s seedy underbelly, and that was the selling of virgin children to men who were wealthy & debased enough that they found no greater pleasure in life than [quote] “the exclusive luxury of revelling in the cries of an immature child.”

Stead didn’t just write about it second-hand — he spent four weeks in the streets, brothels, and hospitals of London, meeting with everyone from doctors and bishops to those deemed “procuresses.” These were people willing to find and broker deals for human flesh and services. He thoroughly documented all that he found, describing the London underworld as a place “with all the vices of Gomorrah, daring the vengeance of long-suffering Heaven.”

The story that unfolded on the pages of The Pall Mall Gazette was horrifying. Stead secured a meeting with a contact who was connected to all sorts of crime in the city’s underbelly. When he inquired about purchasing a virgin girl for his pleasure, he was told that wouldn’t be a problem. When Stead began to ask more questions about any potential consequences attached to his actions, he was further assured that screams would not be investigated and legal action would not be pursued. He quoted his source as saying, “Whom is she to prosecute? … who would believe her?”

Stead, incredulous, asked for confirmation that these unspeakable procurements were common, and was not only assured that they were, but was told, “And you cannot help it, as long as men have money, procuresses are skillful, and women are weak and inexperienced.”

It was something the stalwart journalist could not walk away from, and could not let continue to happen while he stood idly by.

But just the word of a seedy soul prowling the shadows of London wasn’t going to be enough to instigate the change Stead wanted to see. He knew he needed proof, and started by finding and interviewing former brothel owners and those whose innocence had been sold. It wasn’t long before he met a working brothel-keeper who promised it would only take him only a few days to find several virgin girls — whose untouched condition was verified by a doctor. Stead backed away from communication with this man, but it wasn’t long before he found one of these virgin girls, grown and turned procuress, who was willing to reach out to old contacts and find him the sort of girl he was asking for. The price? £3 to £5.

As Stead waded deeper, he found that crude medical procedures and violent assaults didn’t bring an end to the nightmare the children were sold into. Many children, most of whom were orphans or had no family to speak of, were generally passed along to brothel-owners to fill their ranks or ended up on the streets making a living any way they could. And there were plenty of options, as Stead would write: “Anything can be done for money, if you only know where to take it.”

Stead was careful to say that he knew everything he said was true, that it wasn’t just sensationalist nonsense… because he oversaw the negotiation and purchase of a 13-year-old girl.

Her name was Lily, and she had a family who agreed to sell her as a household servant. A procuress paid her parents £5, and she bid them goodbye. She was washed and dressed, and Stead’s description of her makes it somehow even more heartbreaking. She could read and write, he wrote of her as “a loving, affectionate child, whose kindly feeling for the drunken mother who had sold her into nameless infamy was very touching to behold.” She was “full of delight at going to her new situation,” he wrote, stressing that even though her parents knew what was going to happen to her, she hadn’t a clue.

Her status as a virgin was verified by a midwife, the purchaser was supplied with some chloroform, and Stead recorded everything — including the names of the people involved. He immediately published the story.

That public was outraged, and Stead got all the reaction he could have hoped for… and then, a little bit more. On a national level, the expose sparked the passing of the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, which laid the groundwork for other legislature designed to protect women and girls who were forced into prostitution, and it also raised the age of sexual consent from 13 to 16 years old.

For the part he played, Stead found himself in front of a judge, brought up on charges of abduction and indecent assault. When Justice Henry Charles Lopes handed out the sentence, he explained that Stead’s experiment had failed, because he hadn’t bought a child for exploitation at all… he had rescued her before anything bad had actually happened to her. And that meant he had published what the judge ruled “a distorted account of the case”, and called it “a disgrace to journalism.” Stead was sentenced to six months’ jail and hard labor, a sentence backed up by the fact he had technically broken the law by getting only her mother’s permission to buy her, not her father’s as well.

The sentence was considered less about the law and more about what Stead had done. Mostly, his jailtime was thanks to the people who truly hated him — the wealthy men in power, the ones whose actions he had a tendency to condemn in a humiliatingly public way.

The eccentric nature of brilliance

After Stead’s stint in jail, he was never quite the powerhouse of journalism he had been. That’s not entirely because of how his expose on child prostitution ended, though; in the grand scheme of things, it was a huge success. But for years, he had preached some unpopular opinions, including advocating for Ireland’s self-governance, as well as forming closer ties with both the U.S. and Tsarist Russia. When he took over at The Pall Mall Gazette, he had decreased his popularity by doing something revolutionary: introducing decidedly American features into British papers, like large-print headlines, bylines for his reporters, and celebrity interviews.

There were a few other things Stead did that raised some eyebrows, including offering his unwavering support to the establishment of Esperanto as a global language, vocalizing his opposition to British military endeavors like the Second Boer War, and suggesting that the nations of the world needed to form something he dubbed Union International, which would have been a version of the United Nations dedicated strictly to global peacekeeping and anti-militarism.

But it was actually an element of his personal life that eventually gave 19th century Britian its biggest pause, as Stead was also a devoted spiritualist who may have been a little too radical, even for Victorian Britain. And that’s saying something — the spiritualism movement had been wildly popular since the Fox sisters claimed to have channeled the spirit of a murdered man in 1848 and established contact with the other side. The idea that it was possible to contact loved ones who had passed on was obviously enticing, and it gained some serious traction within a select sliver of the population, including Stead.

Stead left The Pall Mall Gazette in 1890, and founded not only The Review of Reviews, but a spiritualist quarterly called Borderland. The publication was a sort of news outlet for the supernatural, and included everything from astrological predictions and news stories about ghosts and seances to reports on research conducted on the occult.

For Stead, this wasn’t a new fascination, either, as he reportedly experienced some otherworldly phenomenon as a young man visiting Hermitage Castle in Scotland. It wasn’t until 1892 that he saw someone practicing automatic writing — the idea that some men and women could channel spirits to write through them. At first, he didn’t subscribe to the idea, but after giving it a try, he claimed to have made contact with an American journalist named Julia Ames. Ames had died in 1891, not long after she interviewed Stead.

It didn’t end with just making contact. Stead went on to write an entire book called Letters From Julia, where he both received messages for a friend of the late journalist and talked to her himself. They talked about grief, about the discovery of the afterlife, of spiritual growth, of loss and of hope. Regardless of how inspirational the letters were, Stead’s obsession with spiritualism serious eroded his credibility in the journalistic world.

But if there’s anything we know about Stead, it’s that he wasn’t easily swayed by an unfavorable public opinion. He went on to found an organization called Julia’s Bureau, which was a group founded with the goal of, according to him, “attempting to bridge the abyss between the Two Worlds.” The idea, he said, was that when loved ones passed on, they weren’t just floating aimlessly or off to sit on some clouds and play some harps. They were more alive than they had ever been before, and in desperate need of comforting the grieving souls who had been left behind.

He appointed what he called “competent sensitives” to the bureau, and their goal was a specific one. They were only to be used by living applicants who were looking to reach out to those they had loved and lost. Stead likened the bureau mediums to policemen who reunited lost and frightened children with their frantically searching mothers. And he wasn’t doing it alone — Julia was on the other side, he said, guiding his efforts.

Julia’s Bureau was only active for around three years, and in that time, they worked with hundreds of grieving people and passed on countless messages. It cost Stead around £1,500 pounds a year to run, and it ended with his death. But that’s not the end of his story.

Eerie prophecies and a sinking ship

Toward the end of his life, Stead was derided and ridiculed for his unwavering belief in spiritualism. And in all fairness, he certainly wasn’t the only believer — Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously became a spiritualist, his beliefs cemented in the face of the senseless loss of life that happened during the First World War. But sometimes it’s only in hindsight that certain things become clear, and in Stead’s case, he penned some eerie tales that will make even the staunchest skeptic think twice.

In 1886, Stead published a bit of cautionary fiction in The Pall Mall Gazette. It was called “How the Mail Steamer went down in Mid Atlantic, by a Survivor,” and it was the story of a steamer ship carrying 916 passengers when it collided with another vessel and sank. The story was in response to legislation that dictated that the number of lifeboats a ship needed to carry was based on the size of the vessel, not on the number of passengers. Stead described the sinking of the ship in agonizing detail, narrating the hundreds of people who had been dumped into the water, the narrator finding himself “amid a blackened, wriggling sheet of drowning creatures.”

The tale ended with the footnote: “This is exactly what might take place and what will take place if the liners are sent to sea short of boats.”

Stead seemed almost obsessed with the idea, and it wasn’t the only time he wrote about tragedy at sea. In the 1892 Christmas edition of The Review of Reviews, he wrote a tale called “From the Old World to the New,” and told the story of the White Star Liner Majestic, whose passengers witness a ship colliding with icebergs, sinking, and ultimately returning to rescue the survivors. He described the sinking in vivid detail, witnessed by one of the passengers on the nearby liner: “The waters bubbled and foamed. I could see the heads of a few swimmers in the eddy. One after another they sank, and I saw them no more.”

Stead often predicted his own death would come at the end of a hangman’s noose, or by drowning. And not only was he right, but in hindsight, that bit of fiction written from the point of view of a man drowning amongst hundreds, and his story about the White Star Liner Majestic and a daring rescue at sea after a collision with an iceberg — that was more prophetic than he possibly could have known.

It was President William Howard Taft who requested his presence at a Carnegie Hall peace congress in 1912, and to get there, he booked passage on the Titanic. His first class ticket cost £26 11s; he charmed other passengers with his stories before he was ultimately among the lives claimed by the disaster. It’s unclear how he spent his last hours; there are various witness testimonies that claim to have seen him in the hours after the Titanic’s fateful collision. Some claim to have seen him reading on the stern of the ship as it rose into the night sky; others say he spent his last hours sitting in the First Class Smoking Room, and still others say he was spotted leading women and children through the chaos and seeing them to the lifeboats.

According to at least one testimony, taken from a survivor named Phillip Mock, Stead actually had made it to a raft alongside Colonel John Jacob Astor. They had been in the water, clinging to the side, and Mock related, “Their feet became frozen, and they were compelled to release their hold. Both were drowned.” Regardless of how he spent his last moments, his Spiritualist associates would later claim he had reached out from the Great Beyond to tell them of the tragedy, and that was how they first heard the news.

His body was never recovered, or at least, was never identified. If his earlier works had been prophetic, he seemed not to have expected his end to come in the way he’d written — at one point, he had also written that he expected to be back home in London by May of 1912.