Welcome to Biographics. Today’s highly recognizably protagonist was hailed as genius of entertainment, a wizard of animation, a pioneer of technology and theme parks. The influence of Walt Disney on today’s popular culture and collective imagination cannot be understated. You can love him, hate him, or love to hate him, but you cannot ignore his work.

Walt Disney once famously said that that laughter is America’s greatest export. It’s not. It’s travel and transportation, with $236 Billion in sales in 2017. But sale of intellectual property, including TV and movies, amount to $49 Billion, which is twice the GDP of Cyprus.

So, if by laughter we mean entertainment, then yes – American entertainment is one of the country’s most important exports, and these days, a good chunk of that intellectual property is owned by Walt Disney Studios: Pixar, Buenavista, and Miramax, plus the Marvel and the Star Wars franchises, are some of the largest and most visible entertainment companies owned by the House of Mouse. Disney’s legacy can capture the imagination of every girl or boy from early childhood all the way through adulthood.

And to think — it all started with the doodle of a mouse, sketched during a depressing train ride home. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves…

Toilet Paper and Start Ups

Walter Elias Disney, later known as Uncle Walt, was born on December 5, 1901, in Chicago, Illinois. His parents, Flora and Elias, were farmers and occasional entrepreneurs of Canadian origin. Walt was the youngest of five siblings, the others being Ruth, Roy, Raymond and Herbert. His much older brothers would prove a source of stability and inspiration later in life.

At the age of seven, Walt and the Disneys moved to Kansas City, where he spent most of his childhood. This was an unhappy period of his life. Elias Sr had a hard time making a living, switching from farming to distributing newspapers. In each of these activities, Walt and his siblings were drafted to work hard and contribute to the family’s welfare. Elias was a tough taskmaster and did not approve of Walt trying to carve out time to do homework or even attend school. You can probably imagine how Elias took to his son’s budding talent for drawing – he considered it a complete waste of time and would not spend a cent on something as futile as art supplies. Walt was reduced to drawing his first sketches on toilet paper.

Walt’s harsh relationship with his father was mitigated by Walt’s close relationship with his big brothers, especially Roy and Herbert, who were an early source of encouragement. Unfortunately, Roy, Raymond and Herbert moved out of the family home eventually, leaving behind the much younger Walt.

In 1917, the US joined the Entente in WWI. Alongside many other patriotic American boys, Walt longed to do his part by donning a uniform to serve in France. He may have also had the added motivation to leave his home behind. Considering the fact that he faked his age to join the army at 16, Walt was likely trying to escape from his home life. Unfortunately, he was rejected for being too short.

Walt had a Plan B: he successfully applied to join the American Red Cross. While training as an ambulance driver, Walt developed his artistic skills, and he became quite popular for decorating the ambulances with cartoons and caricatures of fellow paramedics. One of his fellow trainees was one Ray Kroc – the legendary CEO of McDonald’s.

Walt’s appetite for action remained unfulfilled; the war was over before he was even deployed overseas. But when he returned home, he had a good reason to rejoice — he found out he had won a scholarship to attend the Kansas City Art Institute. After years of having to draw on toilet paper and ambulances, the poor guy deserved a break. And proper art supplies!

While attending the Art Institute, Walt developed a fascination for the growing genre of animation. Animated shorts were commonly used at the time in movie theatres as a crowd-pleaser before the main feature. But they were crudely made, the soundtrack was irrelevant and some of them were just creepy as hell.

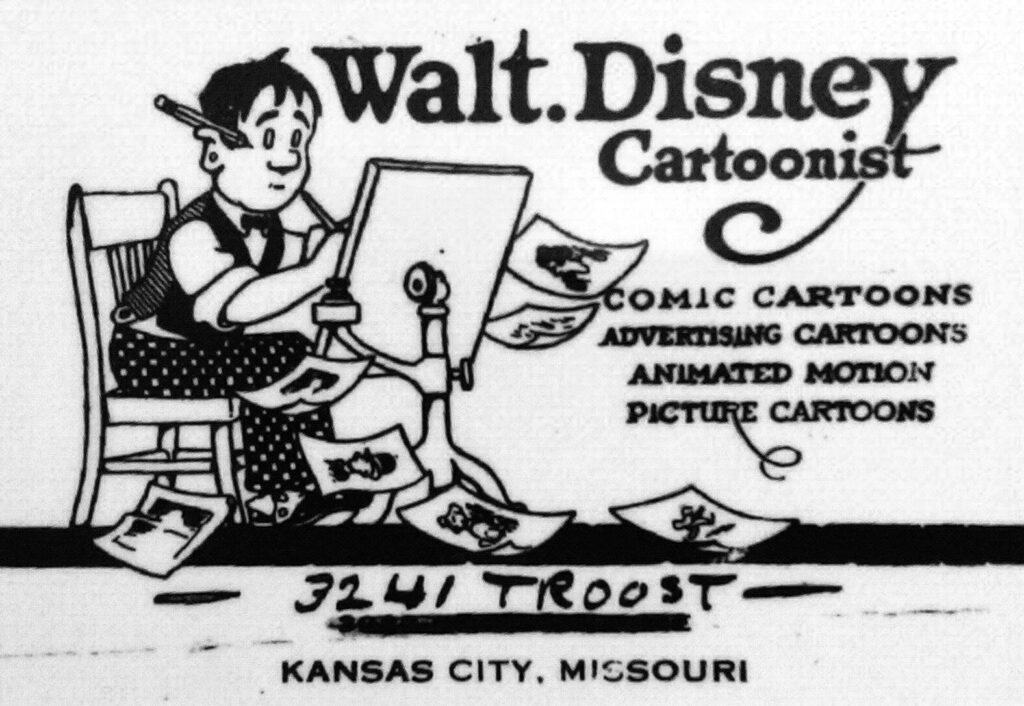

Walt saw an opportunity to fill a potential gap in the market with products of good quality. With a friend from the Art Institute, Ub Iwerks, Walt set up his first animation company. It was a bold move, considering that the two were nineteen and had little to no capital to start with. Walt and Ub developed a series of short animated movies for the Newman chain of cinemas entitled “Newman’s Laugh-O-Grams“.

The company was short lived, running from 1920 to 1923, but its cartoons were a hit with audiences. Walt experimented with some of the themes that would become a staple of his later production: anthropomorphized animals, innovative takes on classic fairy tales, a keen ear for popular music – jazz at that time – and slapstick humour.

Though Walt and Ub were talented animators, as businessmen, they were, well … they were pretty rubbish. The production costs of their shorts were too high, and they signed unfair distribution deals. They thought they had hit jackpot when a distributor company called Pictorial Clubs of Tennessee promised $11,100 for six cartoons – $142,000 in today’s money. But Pictorial never paid, and the Laugh-o-gram company soon went bankrupt.

Interest aside here: if today, some Laugh-o-grams are still in tact and available, it’s thanks to those Pictorial Clubs scoundrels – they kept the six cartoons in their vault and reissued them when Disney had become a household name.

The fellow animator, and other employees of Walt’s start-up, were about to call it quits. But Walt had a brilliant idea, with great potential: how about mixing live action with animation? Walt’s pitch was to film a series of shorts starring child actress Virginia Davis with an innovative technique: mixing a live-action protagonist with animated characters and settings.

Walt and Ub moved to California to start work on this new series, entitled the “Alice Comedies”. Their early work attracted the attention of a New York based distributor, Margaret J. Winkler. Disney’s work was again plagued by high production costs, which made the first Alice Comedies unprofitable. On Winkler’s insistence, Walt and Ub were forced to increase their rate of production, while lowering the animators’ salaries. By this time big brother Roy Disney had joined the company and he seemed to have a much better business sense than Walt. He would remain his business partner and trusted advisor for the rest of his life. It was perhaps on Roy’s advice that Walt and Ub decided to hire an entirely female crew of colourists.

Traditional animation requires for each frame of a cartoon to be coloured by hand. That’s 24 frames per second of footage. So, it’s a meticulous, repetitive, time consuming job requiring large numbers of skilled professionals. At that time, women’s wages were much lower than men, which meant big savings for the Disney brothers.

One of the colourists was a young woman from Idaho called Lillian. At the end of a long day’s work, Walt would routinely drive home a group of his employees. Whatever the route, he would always make sure that the last person to be dropped off was Lillian, so that he could spend more time alone with her. Lillian probably got the hint, and the two started dating. This led to a short engagement, and, eventually, their wedding, in July of 1925.

By 1927, American audiences had grown weary of the Alice Comedies shorts, and Walt wanted to diversify his production. He started working on a new character, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. This series was successful, and Walt considered rescinding his contract with Margaret Winkler to chance distribution on his own.

But in 1928, Walt discovered that Margaret and her husband, Charles Mintz, later of Universal Pictures, were masters of the fine print at the bottom of contracts. During a business meeting in New York, he learned that, as part of his deal with Winkler, every intellectual property developed within the terms of the contract would be legally owned by Winkler and Mintz.

Unbeknownst to him, the New York power couple had another nasty trick in reserve. Their pushy demands and deadlines for the Alice films alienated Disney’s animators. Most of them had vented their frustration against Walt – rather than Winkler. So, when they eventually quit the company, they were hired en masse by Universal! Only Iwerks would remain by Walt’s side.

While riding the train back to California from New York, a depressed Walt Disney put pencil to paper to soothe his sadness and frustration. Little did he know, that doodle would change his life, and have a huge impact on the lives of millions of children. The character he sketched that day was the immortal Mortimer Mouse.

House of Mouse

‘Mortimer who?’ you may ask. Well, that character was Mickey Mouse, but Walt’s initial choice of name was Mortimer. Luckily Lillian talked him to his senses and advised he change the name to Mickey. If you are into this sort of thing, the name “Mortimer” is of old French origin and means ‘Dead Sea’ – not the cheeriest of names for a talking mouse!

Walt’s company was now called Walt Disney Cartoons. A skeleton crew which included only him and Ub on drawing and animation duties, with Roy supervising the business, and his wife and Edna colouring and inking with Lillian. The gang soon delivered three Mickey Mouse cartoons. The first two did not sell. For the third one, Walt had the intuition to add a recent cinematic innovation: a synchronized soundtrack, which included a catchy whistling tune.

This third cartoon was ‘Steamboat Willie.’ It opened on November 18, 1928, and it was an immediate success for Walt Disney Cartoons. Finally, the big break had arrived and the company would produce a string of hit animated shorts. In 1929, they created the cartoon series ‘Silly Symphonies’.

A 1932 episode, Flowers and Trees, was the first cartoon to be produced in colour and to win an Oscar. The follow-up, the Three Little Pigs of 1933, was so popular that it got top billing above the feature films it accompanied.

While working on the Silly Symphonies, Walt and Lillian were trying to conceive a child. Unfortunately Lillian suffered several miscarriages which caused Walt to experience a nervous breakdown. Eventually, a baby girl named Diane arrived in 1933. The Disneys decided to adopt another girl, Sharon, in 1936.

The successes of his cartoons and a growing family emboldened Walt, who now started to think big: why should cartoons be developed only in short format? Why not produce a full-length feature animated film?

Your wish will soon come true

In 1934, Walt started working on that idea: a cartoon that ran the length of a feature film. As he had done previously, Walt sought inspiration from a classic Fairy Tale: Snow White by the Brothers Grimm.

Nobody in Hollywood believed in Walt. Among the studio lots, film executives sneered at the project, calling it “Disney’s Folly”.

The production was not easy, going over time and over budget. But when Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs opened on the December 21, 1937 it won immediately the hearts and minds of both audiences and critics. Including subsequent releases, and adjusting for inflation, Snow White is the tenth highest grossing movie of all times. At the 1938 Academy Awards, the film was nominated for best soundtrack and received a Special Award for ‘significant screen innovation’ – in the shape of one normal-sized Oscar and seven little statuettes.

Walt Disney Studios continued working on shorts, but the main production focus was firmly on feature-length cartoons. Walt’s next two projects were incredibly ambitious: he released Pinocchio and Fantasia, both in 1940. Pinocchio was a relative success – not as astounding as Snow White – but Fantasia tanked. If you haven’t seen it yet, press pause, go and find a DVD, a VHS, a Betamax, whatever, and watch it now.

Welcome back. Seen it? Did you like it? I told you it was awesome! But 1940 audiences did not agree with our modern sensibilities, and for the next production, Dumbo, Walt had to tighten the belt and reduce costs to a minimum. Dumbo’s artwork and animation are visibly cruder than the three previous movies, and the runtime is also quite short – but the film was highly profitable. This relative reduction in quality may have also been a consequence of a studio animators’ strike, an event which deeply angered and worried Disney.

Boss Disney

A 2006 biography of Walt Disney by Neal Gabler sheds some light on Walt’s relationship with his employees, trade unions, and communism. To put it simply, Walt Disney was a tough boss to work for: it is no surprise that his employees wanted to organise themselves in a union, but he considered industrial action as a dangerous expression of communist tendencies.

Think of this example. When Walt turned 35, his brother Roy encouraged employees to throw the boss a surprise birthday party. Two of the animators thought it would be a fun idea to create a short cartoon of Mickey and Minnie Mouse … going at it. (Wink wink, nudge nudge.) When Walt saw the animation at the party, he laughed hard and asked who had made the film. The two animators stepped up, expecting a pat on the back or a handshake. He fired them on the spot.

In general, Walt could be controlling and asked a lot from his employees, resorting to humiliating dress-downs if they did not deliver. Even Roy was not spared. The business brain behind Walt Disney studios was frequently scolded when he offered an opinion on artistic choices.

Uncle Walt’s employees, animators, and cartoonists were the ones subject to longest hours and grueling work conditions. Taking a break was a luxury, as Walt would often appear suddenly in the drawing rooms to check on their work. Luckily for the employees, Walt was a heavy smoker: with time he had developed a persistent cough that announced his arrival by a few seconds!

When his cartoonists tried to form a union, Walt reacted by hiring armed guards, firing organisers, and cutting wages. Well, the 1941 strike … but he really asked for it!

On the July 2, 1941 Disney published an advert in Variety, accusing the strike leaders of ‘Communistic agitation’. This concern about Communist infiltrations in Hollywood led him to join the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, or MPA.

Founded in February 1944, the MPA was an organisation composed of high-profile showbiz personalities with the purpose of defending Hollywood – and America as a whole – against Communism and Fascism. The MPA was active until 1975 and notable members included John Wayne, Ronald Reagan and Ginger Rogers to name a few.

The MPA volunteered to testify in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The Committee was created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and organizations suspected of having Communist ties.

Walt also participated in the hearings of the committee, accusing several leaders of the animators’ strike of being Communist agitators. His testimony earned him the gratitude and friendship of legendary FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover – one whose life we’ll tell sooner or later.

Hoover and Disney developed a strange artistic partnership. In the following years, J. Edgar allowed Walt Disney Studios to film some of their live action movies at the FBI headquarters in Washington. Walt, on the other hand, agreed to submit some of his scripts to Hoover for an early revision, to ensure that the FBI was depicted correctly, but apparently, Hoover did not make any changes to the classic animated films. This is an odd refrain he would have slashed half of Peter Pan’s script for depicting an anarchist commune and abuse of substances that literally get you flying.

In addition to these exchanges of favours, Hoover had Disney appointed as ‘Special Agent in Charge Contact’ in 1954. In other words: a trusted informer and collaborator of the FBI.

Fun fact – decades after Walt Disney’s death, his company would pay homage to the FBI chief with a minor character: J. Gander Hooter from TV series Darkwing Duck.

In the 1950s Walt Disney eventually distanced himself from the MPA, as he lost interest in their ideals and their paranoid approach to anti-Communism. Walt’s association with the MPA is the source of the rumour that he was anti-Semitic, but biographer Neal Gabler, otherwise a harsh critic of Disney’s, dismisses this claim as unsubstantiated. Walt regularly hired or had business with, Jewish employees and colleagues. In 1955 he was even appointed ‘man of the year’ by the B’nai B’rith International, a Jewish cultural organisation. This is not the only persistent, unfounded rumour on Walt, more on this later.

A Triumph of the Imagination

In the 1950s and 1960s Walt Disney studios produced a series of animated masterpieces that won well-deserved popular success. I’ll list them all, because I know if I miss one, I’ll get backlash in the comments: Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), Peter Pan (1953), Lady and the Tramp (1955), Sleeping Beauty (1959), 101 Dalmatians (1961) and Mary Poppins (1964).

Everybody has a favourite of course, but what about your least favourite? Write your vote in the comments and tell us why you chose it!

My personal favourite? Why! ‘tis Mary Poppins of course! Not only Dick Van Dyke’s spot on cockney accent reminds me of my relatives in London … but it’s Disney’s first superhero movie if you think about it – long before the Marvel acquisition came along. Mary has the powers of

- Flight

- Telekinesis

- Interdimensional travel

- Mind manipulation through the medium of song

- Infinite storage capabilities

So, yeah, studio executives, when you are planning the next Avengers film, how about you draft in Poppins, too?

Mary Poppins successfully merged live-action and animation in colour. Before that, Disney studios had ventured into purely live action films, the first one being Treasure Island in 1950. Disney was also one of the first Hollywood producers to invest in TV. The first of his series on the small screen was The Magical World of Disney – which actually can be considered an early example of Content Marketing to promote a good or service.

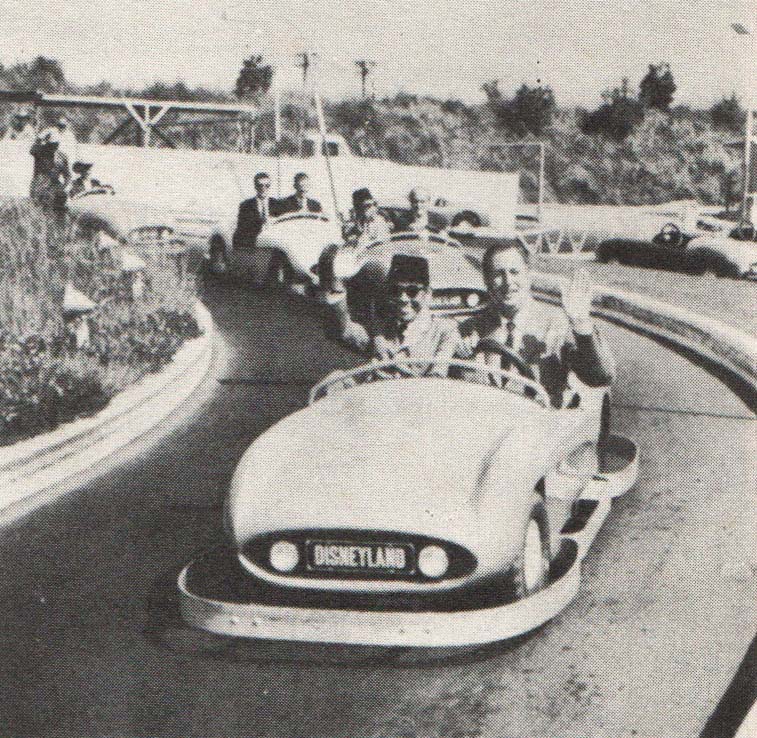

What was Disney promoting? His next big dream, the one that would take most of his energy and attention for the last decade of his life, was a massive, innovative theme park in Southern California: Disneyland.

The park was developed in the town of Anaheim after demographics experts convinced Walt that it would become a major population centre within 10 years. Time would prove they were right, when local population, and park visitors, soared.

Disneyland opened on the July 17, 1955 and its first day was a disaster. 30,000 people turned up instead of the projected 15,000, meaning restaurants were soon out of food and drink. A plumber’s strike forced Walt to choose: either have flushing toilets or working drinking fountains. He chose the toilets. One of the attractions was so overgrown with weeds that Disney ordered to place around placards with Latin names. To disguise the shrubbery as an arboretum, in other words!

Of course, everything improved, and Disneyland became one of the most, if not the most visited and successful theme parks Worldwide. When looking at visitors’ stats, Disney realised that only a small fraction came from the West Coast. That’s when he got the idea of building a sister park in Florida, Disney World, developed around the prototype of a futuristic perfect city, called EPCOT.

But Walt Disney would not live to see his new dream come true. For most of his adult life he had been smoking three packs of unfiltered cigarettes, every day. His daughter Diane tried and failed, to convince him to cut back. They reached a compromise: he would at least smoke three packs of filtered cigarettes – but he just removed the filters behind Diane’s back!

Inevitably in 1966, Walt Disney was diagnosed with lung cancer. He underwent surgery, but due to post-operative complications, Walt had a heart attack and died on December 15, 1966, at age 65.

Contrary to popular and persistent rumours, his body was NOT cryogenically preserved and/or hidden in a vault under Disneyland. Walt was simply cremated, and his ashes were interred at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.

Legacy

I hope you forgive me for stating the obvious, but Walt Disney was and still is, a controversial figure, as is normal for somebody whose influence on the surrounding world and society is larger than life. A personality like Disney will never be free from exaggerations, slander and rumours – or, the opposite risk is to portray him exclusively in a saintly light.

For sure, Walt Disney was certainly not the fairest of business leaders, not the most balanced of workplace bosses, not the most level-headed when confronted with different political ideas. But it is also true that he did deliver a lasting impact on society, culture, and children through his innovative work. As Walt once said:

“I’d rather entertain and hope that people learn, than teach and hope that people are entertained”