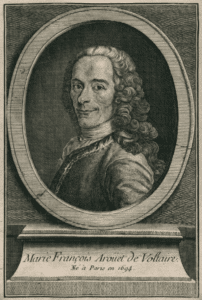

The life of Voltaire was one of extremes in all things. Born weak and sickly, to the point he was not expected to survive more than a few days, yet he lived to the age of 84. During that extended lifetime, he knew the inside of royal courts and French prisons. A Parisian at birth, he spent much of his life exiled from that city. Once a close companion of the Crown Prince of Prussia, he was banished from Prussia when his former friend became King of Prussia, known to posterity as Frederick the Great. He often disavowed his own writing, and used a known 178 different pseudonyms for his work, as well as publishing his earliest efforts using his birth name, Francois-Marie Arouet.

He ridiculed the debauched lifestyles of the nobility he patronized yet engaged in considerable debauchery himself. Despite, or maybe because of, a Jesuit education he satirized what he perceived as the hypocrisy of Christianity, especially that of the Catholic Church. Sales of his many works made him fabulously wealthy, a wealth enhanced by shrewd investments. He became a leading figure of the historical period known as the Age of Enlightenment. The historian Will Durant called the same time period The Age of Voltaire in Volume IX of the epic historical work The Story of Civilization.

Voltaire, in his plays, poems, essays, novellas, and scientific papers, argued against slavery, criticized organized religions, and questioned the legitimacy of absolute monarchies. He used history, science, nature, and humanity itself to argue for the existence of a Supreme Being, though he strongly opposed organized religion. Most of his life included a battle for free speech.

He wrote to kings and princes, suggesting actions which affected nations, such as Frederick the Great, who was then considering war in Europe. “While loving glory so much, how can you persist in a plan which will cause you to lose it?”. Yet he also wrote to the common people; “The husband who decides to surprise his wife is often very much surprised himself”. Of Christianity he opined, “Ours is assuredly the most ridiculous, the most absurd and the most bloody religion which has ever infected this world”. Yet he was equally dismissive of Islam and Judaism. Over the course of his long life his views changed, yet he remained unalterably opposed to the dogmas of religious authorities, writing to Frederick the Great: “…anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit injustices”.

Though he opposed absolute power of government, he was equally suspicious of democracy, calling it, “the idiocy of the masses”. Impossible to sum up, his life was one of constant questioning, of authority, of nature, of his fellow man, and of morality. His was a life of extremes indeed.

My Motto is To the Point

Francois-Marie Arouet was baptized in Paris in November, 1694, the son of an affluent lawyer and court functionary who, by marriage, held minor privileges in the hierarchy of French nobility. Voltaire later disputed that the man who gave him his name was his actual father, claiming to have been born in February, 1694, as the illegitimate son of another nobleman. Sickly and slight as a child, he displayed a quick mind and an eagerness to learn. His formal education began at the age of 10 when he entered the Jesuit College Louis le Grand, situated on the Left Bank of the Seine in Paris. He later praised his education highly, writing of the priests:

“They inspired in me a taste for literature, and sentiments which will be a consolation to me to the end of my life…I had the good fortune to be formed by more than one Jesuit…all their hours divided between the care they took of us and the exercises of their austere profession”.

Voltaire left the College after graduating at the age of 17, desirous of making his career as a writer. His father intervened, insisting his son prepare for a career in the law. The younger Arouet resented his father’s implication that a career in literature was a guarantee of destitution, though he accepted, at least on the face of it, his filial duties for the next three years. He joined with other minor nobles and Abbes (a title similar to “Father” though not necessarily an ordained priest) in enjoying the opportunities for revels during the Paris evenings. Of his legal studies, he expressed his displeasure, writing of, “… the profusion of useless things with which they wished to load my brain…” He professed his motto at the time as being jusqu’au point (to the point).

In 1713, his father obtained for the son an appointment with the Ambassador at the Hague as an assistant. There, the younger Arouet again found the attractions of night life more appealing than legal work, and started a relationship with Olympe Dunoyer, whom he called “Pimpette” and to whom he wrote, “…never was there a person better worthy of love than you”. His employer notified the father of his waywardness, and Francois-Marie was ordered to return to Paris, threatened with disinheritance if he did not address himself fully to the study and practice of law. When Pimpette rejected his advances, Francois-Marie decided to accept his father’s judgment.

To the Bastille

The French King Louis XIV died in September, 1715, leaving as his heir his great-grandson, Louis XV, at the time all of five years old. A regency was called for to save the monarchy, and court intrigues and maneuvering among factions desirous of controlling the boy-king created division in the French government. Philippe, Duc d’ Orleans and the king’s uncle, became Regent, supported by allies among the nobility and the clergy. Louis XIV had distrusted Philippe, referring to him as a “fanfaron de crimes”, or one who bragged about his crimes.

Francois-Marie, while giving lip-service to the practice of law, had already begun to write both poetry and plays. He also enjoyed the salons and entertainments of the nobility, where his wit and often wicked sense of humor made him popular. He described himself as “…thin, long, and fleshless” and enjoyed the freely flowing wine at the salons, regaling other guests with his poetry liberally laced with heresies and barely concealed innuendo directed at some of the more powerful nobles in the regency.

One such poem, described as “very satirical and very impudent” by a contemporary, the Duc de Saint-Simon, led to the young Arouet’s first exile. In 1716, he was evicted from Paris, to Tulle. His father intervened with the target of the verses, the Duc d’Orleans, persuading him that the exile be made to Sully-sur-Loire, still an embarrassment but considerably closer to Paris. While there, Arouet denied he had written the offending verses and begged to be released from what was, in effect, house arrest. By the end of the year, his request was granted, and he was back in Paris, once again titillating the salons and their patrons with his irreverence and his often bawdy verses which only thinly veiled their references to the Regent, the Duc d’Orleans.

In early 1717, a group of verses appeared – Arouet denied their authorship – which included a line which translated read “A boy reigning; a man notorious for poisoning and incest ruling…” The boy referred to young Louis XV, the man the Regent, Philippe, Duke of Orleans. It had long been rumored the Duke’s late first wife had died of poisoning. There were also rumors of his being in an incestuous relationship with his daughter, though these were never confirmed. The Regent responded to the verses by issuing a lettre de cachet (essentially a secret arrest warrant) and Francois Marie Arouet found himself sent to the Bastille in Paris, without benefit of trial. His first incarceration in the prison began in May, 1717.

Love Truth, but Pardon Error

No longer needing to make the appearance of practicing law while in the Bastille, Arouet took to writing to pass the weeks of imprisonment. Denied paper but allowed books, he wrote between the lines of the latter. One of the books he was allowed, at his own expense, was Homer’s Iliad. Arouet began an epic poem of his own, based on Henry IV of France, which he titled La Henriade. He also worked on his play Oedipe, already scheduled to be staged by the Comedie Francaise in Paris in 1718. During his imprisonment he began to sign his name as M. Arouet de Voltaire. He also used the name to sign the letters he dispatched to the Regency, begging forgiveness and for release. It was in that name that his release was granted.

It was not long before the Arouet portion of the name was dropped, and he became known across Europe as simply Voltaire. He was allowed to return to Paris in October, 1718, in time to oversee the production of Oedipe, a play which included the theme of incest. With characteristic cheek, Voltaire asked the Regent if he could dedicate the new play to him. The Duke of Orleans refused, though he allowed a dedication to his mother to be read at the premiere. The play was an immediate sensation in Paris, playing for 45 performances, an unheard of record at the time.

When the Regent had the production moved to his palace for a command performance, Voltaire was summoned to attend as an honored guest. While Paris gossip linked the incest within the play to the rumored incest within the Regency, its author enjoyed the plaudits of the man ruling France. The success of the play, of his Henriade, and other works and essays brought Voltaire financial rewards, critical acclaim, and a notoriety he cheerfully exploited. He was wealthy, influential, and popular, yet his fame had created enemies, and his legal difficulties were not yet over.

In 1726, Voltaire attended a performance at the Comedie Francais where he encountered the Chevalier de Rohan, who made a sneering comment regarding the writer’s adopted name. Voltaire retorted with a comment of his own. While sources disagree on the writer’s exact words, the gist of his retort was that his name was being elevated to glory, while Rohan would bring his own infamy. Rohan was not about to let the insult stand. He sent several of his hirelings to assault Voltaire.

When the enraged writer responded by publicly challenging Rohan to a duel, which was illegal, the Chevalier used his influence to obtain a letter de cachet sending Voltaire to the Bastille yet again. Voltaire, who by then had considerable influence in the Royal Court himself, asked for a voluntary exile in England rather than another lengthy incarceration. It was granted. After two weeks in the Bastille, the writer was escorted to Calais, where he embarked ship for England, arriving there in May, 1726.

What Are We to Think of Human Reason?

In England, Voltaire was welcomed and entertained by luminaries including the British satirist Jonathan Swift, the dramatist William Congreve, and the poet Alexander Pope. He debated with political leaders, aligned himself with Sir Robert Walpole and the liberal Whig party, and attended productions of Shakespeare’s plays, then little known in France. In an essay written during his British exile, Voltaire wrote that the leading British thinkers. “…would have been persecuted in France, imprisoned at Rome, and burned at London…”. Voltaire observed that human reason, “…was a native of England in the present age at least”.

In all his observations and conversations, his correspondence and his essays, Voltaire came to recognize the superiority of a constitutional monarchy rather than absolute monarchy (or democracy) as a form of government. He also came to appreciate the religious tolerance then enjoyed in Britain, at least in comparison to the intolerance prevalent in France. He prepared an English edition of his Henriade, presenting a copy to the Queen, and sold others on subscription. He also began work on his Lettres Philosophiques sur les Anglais (Philosophical Letters on the English). In them he expressed admiration for the British government, the monarchy, their religious tolerance, and their industry, economy, markets, and general society.

The 24 letters, or essays, contained numerous examples of Voltaire’s biting wit. In the fifth letter, which favorably compared the Church of England to Roman Catholicism for the most part, Voltaire was nonetheless disapproving of some of the actions of the clergy. “The English clergy have retained a great number of the Romish ceremonies”, he wrote, “and especially that of receiving, with a most scrupulous attention, of their tithes”. He was especially scathing on Presbyterianism and what he perceived as its hypocrisy, noting that entertainments from theater to playing cards were banned on the Sabbath, except that a “…person of quality, and those we call genteel, play on that day; the rest of the nation go either to church, to the tavern, or to see their mistresses”.

…In Short, She Makes me Happy

In 1728, Voltaire was permitted to return to Paris, where he published and produced several plays, including some imitations of the works of Shakespeare. They were met with limited praise, though another play, Zaire (1732), was a rousing success. His Lettres Philosophiques sur les Anglais was published in Rouen, and Voltaire found himself once again in trouble with the authorities. They found critical comparisons with the British unpalatable. Forced to flee Paris to avoid jail or worse, Voltaire sought refuge with his new mistress, the Marquise de Chatelet, at Cirey, near the border with Lorraine. Joining them at her chateau was the Marquise’s obviously open-minded husband, the Marquis de Chatelet. To assuage whatever husbandly outrage the Marquis may have harbored, Voltaire’s deep pockets paid for restoration of the chateau. Voltaire maintained his home at Cirey for the ensuing sixteen years, writing of his relationship, “she makes me happy”.

It was while at Cirey that Voltaire and Frederick of Prussia, then Crown Prince, began what became a lengthy correspondence and an on and off friendship. Voltaire also occupied his time writing plays, and essays on history, science, the Bible, and organized religion. He also began to move about France and Europe more freely as the passage of time lessened the fervor over his various indiscretions. During a 1744 visit to Paris, he began another affair, with Marie Louise Mignot, his niece who was recently widowed.

Voltaire never married, preferring the company of other men’s wives for his mistresses. His only long-term relationships with women were with the married Marquise and his widowed niece. Nor did he father any known children, though the Marquise became pregnant in 1748, and died during childbirth in 1749. His relationships with both the Marquise and his niece may have been more platonic than sexual, according to some. Such would be in accord with what Voltaire wrote years before at the age of just 25. “Friendship is a thousand times more precious than love. It seems to me that I am in no degree made up for passion. I find something a bit ridiculous in love…I have made up my mind to renounce it forever”.

More is Possible Than People Think

Following the death of the Marquise and a brief visit to Paris, Voltaire moved to Prussia at the invitation of Frederick, by then King of Prussia, but not yet Frederick the Great. There, while living under Frederick’s protection and on his payroll, Voltaire produced Micromegas, an early work of science fiction in which extraterrestrials visit Earth and observe the foibles of the human race. In answer to a human’s question comparing the natural and the supernatural, Voltaire’s alien expounds, “…I say again that nature is like nature. Why bother looking for comparisons?”. The alien observes human reason is limited, the universe limitless.

At the same time, as he had in the French Court years earlier, Voltaire made enemies as easily as he amused his friends and patrons. By mid-1752, Voltaire was no longer welcome at Frederick’s court, having, as he did so often throughout his long life, made powerful enemies among the nobility and influential religious leaders. Frederick banished him from the court, though the two remained correspondents.

As he slowly journeyed back towards France and Paris in 1754, he learned that he was once again banned from the French capital, where his enemies accused him of spying for the Prussians. With enemies behind him and before him, he turned left, settling on an estate near Geneva. There he published another epic poem, La Purcelle (The Maid of Orleans). In his earlier Henriade, he had made a national hero out of the relatively unknown Henry IV. In La Purcelle, he lampooned a national heroine, Joan of Arc, and her legend for the religious aspects of her story. It was banned in most of France, as well as in Geneva, due to its frequent licentiousness and near pornographic imagery. Voltaire left Geneva and settled on an estate at Ferney, just inside France, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Let us Cultivate our Garden

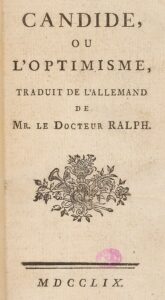

In 1759, Voltaire published Candide, arguably his best-known and certainly his most widely-read work today. Its hero, Candide, his mentor Dr. Pangloss, and a host of colorful characters endure calamities and misadventures in a fictional world. Voltaire used satire and parodied historical events, including the 1755 Lisbon earthquake which killed an estimated 40-50,000 people. Religion, the military establishments, war, philosophers, charlatans, and humanity itself are all targets for Voltaire’s prose, dispatched with humorous contempt.

Candide also contained a condemnation of slavery, one of many throughout Voltaire’s canon. When the naïve Candide encounters a slave in French Guiana, mutilated in an attempted escape, he gasps at “…what price we eat sugar in Europe”. The enslaved victim gives the opinion that if all humanity shared common ancestry, as described in the Book of Genesis, then all were related, and “…no one could treat their relatives so horribly”.

Candide discovers a utopian society dubbed El Dorado, where he encounters a humanity freed of religious dogma, a paradise governed by human reason. When he asked if the citizens therein prayed to a God, he received the reply, “We do not pray to him at all. We have nothing to ask of him.” Yet to Voltaire, the seemingly perfect world of El Dorado could not exist. If all were truly equal in all things, as its citizens claimed, then any discontent in one must reflect in another. The best of all possible worlds for one is not necessarily the best for all.

Candide derides the then popular philosophy of optimism, with its frequently repeated observation that no matter how bad a situation appears, it is for the best, another way of repeating that it is God’s will. When a man encountered during Candide’s travels asks of optimism, “What is that?”, Candide replies, “It is the obstinacy of maintaining that everything is best when it is worst”. Having observed that life is full of thorns, Candide arrived at the belief that all must “cultivate our garden” in the manner most suitable to their own existence.

The book was immediately banned or censored throughout France as being blasphemous, seditious, and scandalous. It eventually came to be regarded as one of the greatest works of French literature ever written.

He followed Candide with his Dictionnaire Philosophiques (Dictionary of Philosophy), a work he had begun while living in Prussia and continued to amend and expand for the rest of his life. The book originally consisted of 73 articles, in alphabetical order, later expanded to 120 entries. Each is a subject of philosophical discussion, often in the form of a dialogue between characters. They range from Adultery to Why?, and point out the inconsistencies and outright hypocrisies of many of the positions of the government, religions, and philosophers over the laws of nature and the natural rights of humanity. It too was banned across France.

I Die Adoring God

In early 1778, the aged Voltaire journeyed to Paris to attend to the first staging of his play Irene. Stricken gravely ill during the mid-winter journey, Voltaire wrote what should have been his epitaph. “I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition”. Then he recovered, attended Irene’s performance in March, and enjoyed the acclaim and applause it generated. By the end of April he was again ill. He died at the end of May, 1778, probably of uremia. After his death, his political and religious enemies claimed that, on his deathbed, he had accepted baptism into the Roman Catholic Church and confessed his sins to a priest. There is no evidence that he did so. Although a priest did attend him and urged him to confess, Voltaire responded by waving him away, uttering, “Laissez-moi mourir en paix” (Let me die in peace).

There is also no evidence that while on his deathbed he responded to the urging of a priest to renounce Satan and replied, “This is no time to be making enemies”. That is but one of numerous quotes misattributed to Voltaire, including one which went viral on social media in 2022, “If you want to know who controls you, look at who you are not allowed to criticize”. Such misattributions play on the continued resonance of the name Voltaire.

The Catholic Church denied his remains’ burial in consecrated ground in Paris, another indication of his refusal to accept conversion. His mistress Marie Louise was the sister of the Abbe of Scellieres in Champagne, and through his influence Voltaire was buried at the Abbey there. In 1791, as revolutionary fervor rocked France, his remains were returned to Paris and enshrined in the Pantheon after a procession attended by over 1 million people.

In 1968, the first volume of the Complete Works of Voltaire, compiled and translated by the Voltaire Institute and Museum in Geneva, was published. In 1976, the project to compile all of Voltaire’s prodigious amount of work moved to Oxford’s Voltaire Foundation. In April 2022, the 205th and final volume of the series was published. According to the Voltaire Foundation, his life’s writings extended to over fifteen million words, covering nearly all aspects of human existence as was known during his lifetime. Based on references in known documents, up to 25,000 letters written by Voltaire have yet to be found. Thus, there may well yet be some unknown pearl of wit recorded by Voltaire that is pithy, irreverent, sarcastic, and still bitingly relevant.