You don’t get to the top without making a few enemies. This was a lesson that Vito Genovese knew well, but it did not deter him in the slightest. His lust for power was so strong that anything other than being the Don of the most powerful crime family in America would have been unacceptable.

There were plenty of obstacles in his way, obstacles that were just as dangerous as he was. But Genovese had no qualms about taking them head-on, which he seemingly did with great success, achieving his goal of reaching the top of the criminal underworld while leaving behind a trail of bodies and victims who felt his wrath.

Early Years

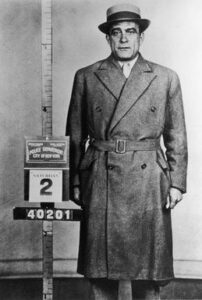

Vito Genovese was born on November 21, 1897, in the town of Tufino in Naples, Italy, one of four children to Frances Genovese and Nunziata Aluotto. When Vito was 15 years old, the family packed up and left Italy, immigrating to America. They arrived in New York and settled on Mulberry Street in the heart of Little Italy.

Pretty much from the get-to, young Vito was up to no good. He started out his life of crime with petty thefts, knocking over pushcarts and the like. Even back then, he looked up to the mustachioed mobsters who held domain over the streets of Little Italy running numbers games and protection rackets. It wasn’t long before he became an errand boy for them, and then later a collector who gathered the lottery winnings. When he was 19, Genovese got busted for the first time for carrying a pistol, which earned him a one-year stint in prison. Despite his efforts and even the jail term to boost his credibility, Genovese was still small potatoes in the Mafia pecking order. His fortunes improved substantially, however, when he allied himself with another promising up-and-comer, a guy whose life and career would intertwine with that of Genovese from then on. A guy by the name of Salvatore Lucania, better known as Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

During the 1920s, Genovese and Luciano worked for a guy named Giuseppe Masseria aka “Joe the Boss.” Masseria ran one of the most powerful crime families in New York City and spent the decade fighting to become the capo dei capi or “boss of bosses,” something which he achieved in 1928 after assassinating the previous boss, Salvatore D’Aquila.

Like many mobsters of his day, Genovese took advantage of Prohibition during the 20s and made a lot of money from bootlegging. He had his own operation together with Luciano and Frank Costello, another man who would play a big role in Genovese’s life and vice-versa, for better or for worse…mostly worse. They were backed financially by Jewish kingpin Arnold “The Brain” Rothstein, and often had dealings with two young Jewish gangsters, Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel. This was something that didn’t always sit well with some of the more old-school mobsters who thought that Italians should stick with Italians and didn’t even like the idea of Sicilians getting into bed with Corsicans. By the way, if you want to know more about any of the names we just mentioned – Luciano, Costello, Siegel, Lanksy, Rothstein – we have already done bios on all of them just waiting for you if you’re looking for your Mafia fix.

Anyway, Masseria’s reign as the undisputed king of New York’s underworld didn’t last very long. Unsurprisingly, with that much power up for grabs, someone else would always inevitably step up to challenge for the throne. That someone was Salvatore Maranzano, a member of the Sicilian mafia who emigrated to Brooklyn to make a play for the criminal operations in New York. To achieve that, of course, he needed to eliminate Joe the Boss. In 1930, this triggered a violent power struggle known as the Castellammarese War after the town where Maranzano was born.

We’ve talked about the Castellammarese War before in some of our other mobster bios so we’re not going to harp on it too much now. Here’s the gist: guys like Masseria and Maranzano thought the old ways worked best. They would fight for power and whoever emerged triumphant reigned as the boss above all others. But the younger guys like Luciano, Lansky, and Genovese had other ideas. They reasoned that, as long as there was one capo to rule them all, the New York families would be trapped in a perpetual power struggle where they would all be focused on killing each other instead of making money. So why not try something new – kill both Masseria and Maranzano, get rid of all the old-world traditionalists, and form the Commission, a sort of governing body for the most powerful crime families in the country where there wouldn’t be just one boss with a final say over everything.

First at the gallows was Joe the Boss. He was killed on April 15, 1931, while playing cards at a restaurant in Coney Island alongside his lieutenant, Lucky Luciano. At one point, Luciano excused himself to go to the bathroom, and four shooters, one of them alleged to be Vito Genovese, busted in and gunned down Masseria.

In exchange for betraying his former employer, Luciano was given control over Masseria’s crime family and became Maranzano’s new second-in-command. But this was all just stalling for time. Five months later, a crew of Jewish hitmen stormed Maranzano’s office and shot him to death. Similar fates awaited all those who were stuck in the old ways and, afterward, the Commission was born.

An Italian Detour

With the Commission in effect, there was no “boss of all bosses” anymore. New York’s Five Families all had a seat at the table, as well as other powerful crime syndicates such as the Chicago Outfit and the Philly Mob. But make no mistake – this was not a true egalitarian society, either. The head of the most powerful family was still the one whose word carried the most weight, and that head was, unsurprisingly, Lucky Luciano. He maintained leadership of Masseria’s former gang, named it after himself, and appointed his two closest associates, Frank Costello and Vito Genovese, as his consigliere and underboss, respectively.

Following this drastic redistribution of power within America’s organized crime network, Genovese found himself the second-in-command of the most powerful mob outfit in the country, so he wasn’t doing too bad for himself. But second would never be good enough for someone like Genovese. Although he aligned himself with guys who wanted to shake up the system like Luciano and Meyer Lansky, deep down he was too greedy and ambitious to work within such a system. He wanted all the power for himself.

There was another matter. While other mob bosses weren’t quite so gung-ho when it came to violence because it attracted unwanted attention, it seems that Genovese only really knew how to solve problems one way – by killing them. A case in point was in 1934 when Genovese and another mobster named Ferdinand Boccia hustled $150,000 out of a high-stakes poker game. Instead of paying Boccia his share, Genovese decided it was easier and cheaper to have him whacked.

With its increased activity, the mob made a few new enemies, chief among them New York prosecutor Thomas Dewey, who had declared war on organized crime. In 1936, he landed his biggest fish—he got Lucky Luciano sentenced to 30 to 50 years on multiple counts of pandering. The appeal failed, and Luciano was headed to prison.

This was bad news for all the members of his crime syndicate except for one person – Vito Genovese, who was now the new acting boss of the family. Sure, Luciano was directing traffic from prison and Genovese was still just basically following his orders, but it was one step closer to the ultimate power that he so coveted.

Unfortunately for Genovese, he did not get to enjoy his position too long. Boccia’s death came back to bite him in the ass, and in 1937 Vito feared that he would be indicted for his murder. With not a lot of alternatives, Genovese had to flee the country, returning to Italy and settling in Naples.

As always, Genovese was an opportunist who tried to align himself with the winning side, regardless of their motives or intentions. Back in his native country, this meant becoming buddy-buddy with none other than Il Duce himself, Benito Mussolini. Genovese used a connection he had with Mussolini’s son-in-law, Count Ciano, whom the mobster generously supplied with drugs, in order to ingratiate himself with the dictator. Later, Vito cemented their relationship by organizing the assassination of one of Mussolini’s enemies back in New York City, the socialist newspaper editor Carlo Tresca. In gratitude, the dictator gave Genovese an Italian Knighthood and named him Commendatore del Re.

Of course, as we all know by now, Mussolini did not win the war. In 1943, the Allies invaded Italy and occupied it. Suddenly, Genovese’s bond with Il Duce went the way of the dodo and he switched sides, becoming an interpreter and liaison officer for the American forces. He was helped by the fact that nobody looked too deep into his background to discover that he was wanted for murder back in the United States. Genovese further ingratiated himself with the U.S. Army by helping them take down a number of black market operatives, omitting the fact that he only did this because he wanted to take over their operations.

This worked for a while but, eventually, an overzealous officer with the Criminal Investigation Division found him out. Not only that, but he uncovered who Genovese truly was and that he needed to be sent back to America to stand trial for murder.

Vito was extradited to the U.S. on June 1, 1945. However, as it often happens in trials against powerful mobsters, the case against him started to fall apart, culminating with the death of the state’s chief witness, Peter La Tempa, who was poisoned while in protective custody. With little choice, the charges against Genovese were dropped in 1946 and he was a free man, ready to take back his place in the family. However, he was about to discover that things were not how he left them nine years earlier.

The Gloves Are Off

While Genovese was away in Italy, Luciano was still in prison and Frank Costello served as the new acting boss, appointing Willie Moretti as his underboss. But during the war, the American government employed the old “enemy of my enemy is my friend” tactic and secretly cooperated with the crime families in an attempt to prevent Nazi sabotage at home. It made sense on paper. After all, the mobs controlled the docks and the black markets, and, in general, were aware of all the shady goings-on in the city, even those that did not directly concern them. Who better to ask for assistance? It was a little something called Operation Underworld and how effective it truly was remains up for debate, but one thing is for certain – it was a great benefit to Lucky Luciano.

As you might expect, Luciano didn’t agree to help out of the goodness of his own heart or a sense of patriotism. He expected clemency for his past convictions and he got it. In January 1946, Luciano was pardoned, ironically, by the same man who put him behind bars – Thomas Dewey – who was now Governor of New York. But his freedom came with a big catch – he was going to be deported back to Italy, never to step foot on American soil again. So when Vito came back into the fold, he found that the boss of the Luciano family was thousands of miles away, while the new boss, Frank Costello, and his right-hand man, Moretti, had no intention of ceding power back to Genovese. Vito had been demoted to a mere captain running his own crew again. Obviously, for someone of his temperament and ambition, something like this would never stand, but he needed to wait and pick the right time.

Also in 1946 came the Havana Conference, a major gathering of all the top mobsters in America, held in Cuba so that Luciano could attend. This was a landmark moment in the history of the American Mafia, considered the most important meeting ever since the Atlantic City Conference of 1929 where all the up-and-coming gangsters decided to whack Masseria and Maranzano and form the Commission. It’s rumored that at this meeting, Genovese approached Lucky in private and suggested that he step down as head of the Luciano family since he couldn’t return to America. To save face, Lucky could declare himself as the “Boss of Bosses” but only in name only, while Genovese would be the one running the family from day to day. Allegedly, Luciano replied:

“There is no ‘Boss of Bosses.’ I turned it down in front of everybody. If I ever change my mind, I will take the title. But it won’t be up to you. Right now you work for me and I ain’t in the mood to retire. Don’t you ever let me hear this again, or I’ll lose my temper.”

Supposedly, Luciano did, indeed, lose his temper, suspecting that Genovese was the one who tipped off the American authorities that he was hiding in Havana. He summoned Vito to his room where Lucky gave him a beating that broke a few ribs and forced Genovese to stay a few extra days in Cuba to heal.

Even if this did happen, Genovese still ended up on the winning side. When the American government found out that Lucky was in Cuba, it withheld all medical shipments to the country until the Cuban authorities arrested Luciano and deported him back to Italy. Running the family from Cuba was feasible. It was just a stone’s throw away from Florida and guys like Meyer Lansky would be there all the time, anyway, to oversee their gambling and narcotics interests in the country. Trying to run it from Italy was a whole nother matter entirely. Regardless of how cool he tried to play it off, being stuck on the other side of the Atlantic severely limited Luciano’s power and influence. He knew it, Genovese knew it, and everyone else knew it, too. As far as Vito was concerned, he had gotten rid of Lucky as much as he could without actually having him killed. Now it was time to focus on his competition back in New York, Costello and Moretti.

First on the docket was the Luciano family underboss, Willie Moretti. Fortunately for Genovese, Moretti made things easy for him by having a big mouth. In 1950, a special committee headed by Senator Estes Kefauver led a large-scale investigation into organized crime, calling many prominent mobsters to testify and, most significantly, showing the whole thing on television. For most of America, this was the first time that they were being exposed to concepts like the Cosa Nostra. Although the other gangsters who had been called in to testify knew how to keep their mouths shut, Moretti was feeling chatty. He didn’t say anything incriminating, but he liked to tell jokes, taunt the committee, and just generally play up to the cameras.

The Mafia was not happy with his actions. There was a belief that Moretti’s actions were the result of his advanced case of syphilis and that, as his mental faculties continued to deteriorate, he would become more and more unreliable. Eventually, with the Commission’s approval, Genovese gave the word to have Moretti whacked in 1951, describing the whole thing as a “mercy killing.” With two out of the way, the only man standing in Genovese’s way of becoming the new head of the family was Frank Costello.

The New Don

Taking out someone like Costello was easier said than done. The man wasn’t known as the “Prime Minister of the Underworld” for nothing. Even with Luciano in Italy, Costello still had connections and his death would not be without consequences. So Genovese waited and waited, slowly but surely building up support for his eventual power play.

He found a major ally in Carlo Gambino, the underboss of the Mangano crime family that would soon be renamed after him. Gambino shared Genovese’s ambition to climb to the top of the ladder and the ruthlessness to get it done. Also like Genovese, Gambino had no love for the current boss of his family, Albert Anastasia, and this was like music to Vito’s ears since Anastasia was Costello’s main ally and muscle in New York. Getting rid of the two of them together was essential in order to secure the top spots for Genovese and Gambino with little fear of reprisals. So in 1957, it was finally time to strike.

On May 2, 1957, Frank Costello was walking toward his apartment in Central Park West when a shadowy figure approached him, raised a gun, and, as he let off a shot, shouted: “This is for you, Frank.”

Costello had no time to react but fate was on his side that day. The bullet only grazed the side of his forehead and knocked him to the ground. Meanwhile, the gunman, seeing his target down, made his getaway in a black Cadillac, not waiting around to check if Costello was actually dead or not.

The shooter was Vincent “the Chin” Gigante, a protégé of Genovese and a future boss of his family. Costello recognized him but elected not to identify him, keeping in line with the Mafia’s code of silence. However, he knew that this was not the end. He needed to find some way to settle things with Genovese, otherwise, it was only a matter of time before he would try again. Therefore, in a somewhat surprising move, Costello relinquished control of the Luciano family and retired, finally allowing Vito Genovese to claim the spot he had so coveted his entire life.

The only loose end left to tie up was Anastasia but the attempt on his life was considerably more successful. On October 25, 1957, two gunmen turned him into Swiss cheese in the barbershop of the Park Sheraton Hotel, ostensibly on Genovese’s orders. Afterward, Gambino became head of the family, renamed it after himself, and endorsed Vito Genovese’s new position as the Chairman of the Commission, in effect, making him the most powerful mobster in America.

Downfall

As the new head of the table, Genovese renamed his crime family after him and insisted on being called “Don Vito.” But this was not enough for him. He still wanted recognition from all the other families. So he did something ballsy, even by his standards – he called another summit like the one in Havana. This one took place on November 14, 1957, in the small town of Apalachin, New York, at the estate of Joe Barbara, the boss of the Bufalino crime family.

Just the fact that Genovese was able to organize this meeting and summon mobsters from all over the country and even from Italy showed that most of the underworld already saw him as the new top dog, but it was nice to make it official. Topics of discussion included any lingering issues left from Anastasia’s assassination and the attempt on Frank Costello, the narcotics trade, and various other rackets.

The Apalachin Meeting was supposed to be Don Vito’s crowning moment, but it didn’t really play out like that. State troopers couldn’t help but notice all the fancy, out-of-state cars showing up at the same time in a small town with a population of 1,000 people. They ran the plates and found that many of the vehicles were registered to known criminals, so they called for reinforcements and set up a roadblock.

There was even a rumor that the authorities were tipped off by Costello and Meyer Lansky, who did not attend the meeting and would have wanted to spoil Genovese’s big day. If this was truly their work, they succeeded. State troopers raided the place and arrested around 60 of the biggest mobsters in the country. Even if they were all eventually released without charge, it was still an inauspicious start for Genovese’s reign as Don Vito.

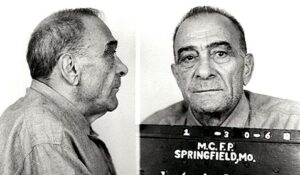

And it didn’t really get any better from there. Genovese enjoyed his time at the top for less than two years before being brought down on drug charges. Again, it was heavily rumored that he was the victim of a conspiracy against him planned by his rivals, Costello, Lansky, Luciano, and possibly even Carlo Gambino, who paid a Puerto Rican drug dealer to implicate Don Vito in the deal and get him arrested.

Once again, if this is true, then the plan worked like a charm and it showed that, oftentimes, deception and subterfuge are more efficient than backstabs and cold-blooded murder. Fifteen people were convicted following the drug bust, including Don Vito who got 15 years in prison.

Sure, he was still the don even behind bars, and would delegate orders, but it wasn’t the same. Not like he envisioned it. Plus, Genovese was still unsure who betrayed him so he ordered hits on several people close to him, including high-ranking members of his own family. One of his targets was Joe Valachi, who was serving a sentence in the same prison as Genovese. But Valachi managed to overpower the hitman sent to snuff him out, and then turned state’s witness in exchange for protection, becoming the first prominent mobster to spill the Mafia’s secrets for all the world to know.

It was one final blunder from the don who showed that you can’t just use violence to solve every situation, not if you want to live without repercussions. Vito Genovese never saw the light of freedom again, dying in prison on February 14, 1969, aged 71.