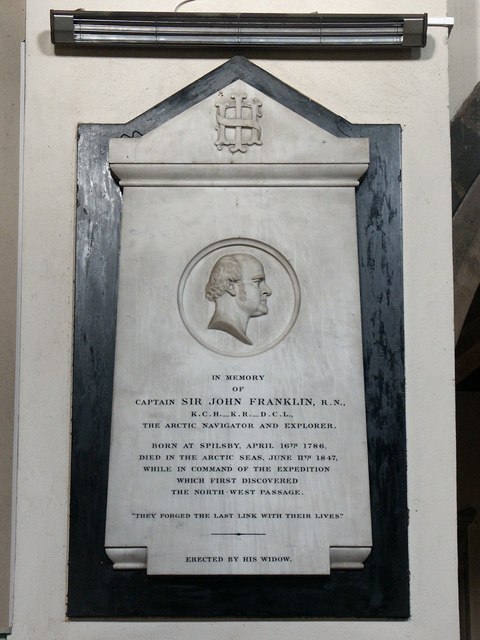

Sir John Franklin was knighted for his first two journeys of exploration to the Arctic. Yet, his third trip to the ice would be prove to be one of the most disastrous sea-borne expeditions of all time. He and his 128 men simply vanished. For nearly a decade a massive search was undertaken. In the end though, it was the perseverance of a wife who refused to let go that uncovered the crew’s terrible fate. In today’s Biographics, we discover the real story of Sir John Franklin and his voyage of terror.

Early Years

John Franklin was born on April 16th, 1786 in Spilsby, Lincolnshire in England. He was the ninth of twelve children to Willingham Franklin and Hannah Weekes. Willingham was a successful merchant, which enabled him to provide a comfortable standard of living for his family.

John attended school at King Edward VI Grammar School. He got his first view of the ocean at the age of ten and it was at that point that he set his mind on a career at sea. His father was not happy with the decision as he had a career in the church in mind for John. Within two years, however, Willingham had softened. He allowed John to experience life at sea by going on a trial voyage on a merchant ship. This experience confirmed for John that this was the life for him.

He joined the Royal Navy at age 14. Within a few months he got his first taste of naval warfare at the Battle of Copenhagen.

At the tender age of fifteen, Franklin served as a midshipman on HMS Investigator. This ship was captained by Matthew Flinders with the mission to chart the Australian coast. Flinders was a cousin to John and he took a personal interest in the training of the eager teenager. Over the course of the two-year expedition, he was hands on in helping the boy get to grips with the fundamentals of navigation and surveying.

After two years, the Investigator became unseaworthy, forcing the crew to transfer to the HMS Porpoise for the home journey. This ship was wrecked on a reef 200 miles north of Australia. Captain Flinders set off with several officers in an open boat en route to Sydney for help. Franklin and the remainder of the crew were left to camp on the narrow reef, using strips of sail for makeshift tents. Six weeks later, Flinders was back with a rescue ship.

Upon his return from Australia, Franklin secured a position as a signals officer on HMS Bellerophon. He was in the middle of fighting at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. He did not suffer any wounds but the roar of cannon fire left him slightly deaf for the rest of his life.

Seven years later, the now very experienced twenty-six-year-old was involved in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. He was at the head of a party that tried, but failed, to capture New Orleans.

By the time of the end of war against the United States, Franklin had risen to the rank of lieutenant. But, seeing that it was a time of peace, there were now fewer opportunities for promotion. For three years, Franklin struggled to secure appointments. Then, in 1819, at the age of 32, he was given the mission of heading an expedition to the Arctic. It was his first command.

To the Arctic

The two ships that were to be used for the Arctic expedition were not naval vessels. Rather, they were whaling ships that had been purchased by the navy. The ship that Franklin was to lead the expedition from was the Trent. The other ship was the Dorothea, with a Captain Buchan on board. The mission was to head north in an attempt to reach the North Pole and then take a direct line to the Bering Strait in order to finds a Northwest Passage.

The mission was predicated on the Open Polar Sea theory. The theory was that the sea temperature increased between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole. By this reasoning, once a ship had broken through the ice sheet north of Spitsbergen, they would be able to make it through. Prior to the voyage, meetings were held in which scientists explained to Franklin and Buchan the rationale behind the theory. Acting on this information, Franklin set himself to making observations on the tides and currents, the depth of the sea, terrestrial magnetism ahd atmospheric goings on during the voyage.

The ships set off from Shetland. Prior to departure the Trent was letting in water. The source of the leak could not be located. It required the men to constantly work the pumps. Franklin tried to recruit sailors from Shetland but many of them refused, stating that they would go to sea on a leaking ship.

This was not a good start. It meant that Franklin set off short-handed and with a vessel that he could not have full trust in. The men had to man the pump and work the windlass at the same time. This put an inordinate amount of pressure on the crew and some of them became overtaken with exhaustion. It took several weeks until the leak was finally discovered and repaired.

In the winter of 1819, Franklin set of on his first overland expedition in the North-West territoriy of Canada. The party stopped off at Cumberland House, which was a fur trading depot on the Saskatchewan River. The supplies that they were expecting to find were not there. A thousand miles further on at Fort Chipewyan they reached another supply station, but again there were no supplies.

Rather than turn back, Franklin carried on, though he had only a single day’s provisions. He told the men that they would hunt and fish to feed themselves. This was a forlorn hope and the men very nearly starved to death.

The expedition eventually made it to the Arctic coast. They were, however, only able to explore 500 miles before the lack of food and harsh winter forced them to turn back.

An overland journey across the so-called Barren lands was an unmitigated disaster. The party of twenty-two men stumbled through uncharted territory in a state of near starvation. For days on end, all they had to eat was lichen. Eleven men died, with the others being rescued by Copper Indians who helped them get to the safety of Fort Enterprise.

Back in England, Franklin was given a hero’s reception. He was lauded for the courage he had displayed during adversity, becoming known as the man who ate his boots for his resorting to chewing on his boot leather while in a state of starvation.

After recovering from the ordeal of his first command, Franklin met and fell in love with a girl by the name of Eleanor Anne Porden. In 1824, they had a daughter, Eleanor Isabella.

In February, 1825 Franklin set out another overland journey. This time he planned to follow the course of the Mackenzie River to the sea and then explore the coast. A week after he left his wife Eleanor died of tuberculosis. Franklin had no knowledge of the tragedy and faithfully wrote letters to his wife until April, at which time he read of her death in a newspaper.

Despite the personal tragedy, Franklin’s second voyage was far more successful than his first. He returned to England in 1827 to much acclaim. The following year he remarried. His second wife’s name was Jane Griffin, who had been a friend of his first wife.

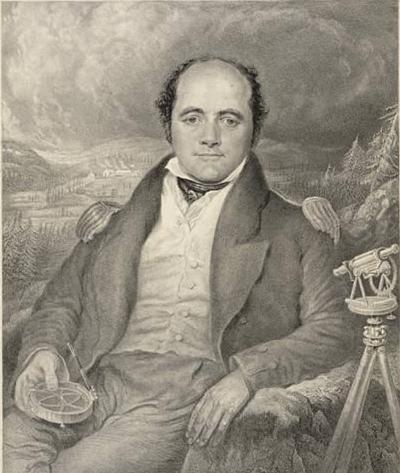

Franklin was knighted in 1829 to recognize his arctic exploration work. During these years on land he put on a substantial amount of weight, perhaps in compensation for his years of starvation on the ice. From 1830 until 1833, he commanded the HMS Rainbow as it patrolled the Mediterranean during the Greek War of Independence. Then, in 1836, he was made lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land in Australia. Today this is known as Tasmania.

Franklin enthusiastically threw himself into the task of reforming the island. But he was stifled by colonial infighting. His colonial secretary, John Montagu seemed to undermine every move that he made. Eventually he sacked the man. Montague complained to the British Prime Minister who agreed that the dismissal had been unlawful. The decision was made to recall Franklin. However, the situation was handled badly with the replacement lieutenant governor arriving in Tasmania four days before Franklin had even been informed of his dismissal.

A deeply frustrated Franklin arrived back in London in June, 1844. The timing was fortuitous as the British Admiralty was planning another Arctic expedition. From the moment he heard about it, Franklin was desperate to lead it. He felt that he was extremely qualified for the job on the basis of his two previous expeditions.

The Admiralty agreed and Franklin was officially appointed to command the two ships that were to undertake the mission. They were called the Erebus and the Terror.

On the strength of Franklin’s previous Arctic expeditions, only about 500 kilometers of Arctic coastline remained unexplored. This latest voyage was designed to complete the task. The command of the Erebus was given to Captain James Fitz James. Command of the Terror was given to Captain Francis Crozier, who had commanded they ship on a previous voyage to the Antarctic between 1841 and 1844. The 59 year-old Franklin was given overall command.

Both ships had been recently outfitted with new technology. The innovations included steam engines, a library boasting more than a thousand books and three years’ worth of preserved and tinned food supplies.

The expedition set sail from Greenhite in England on May 19, 1845. In total there were 24 officers and 110 men. They headed north, picking up supplies on the Orkney Islands. They then set a course for Greenland. They were escorted by the HMS Ratttler and a transport ship named the Barretto Junior. Next stop was Disko Island, in Baffin Bay off the west coast of Greenland. Here five men were sent home on the support ships due to illness. This brought the final crew number down to 129.

The two ships and the men onboard were last seen by European’s on July 26, 1845. On that day, the whaler Prince of Wales came across the two ships alongside an iceberg in Lancaster Sound, between Devon and Baffin Islands.

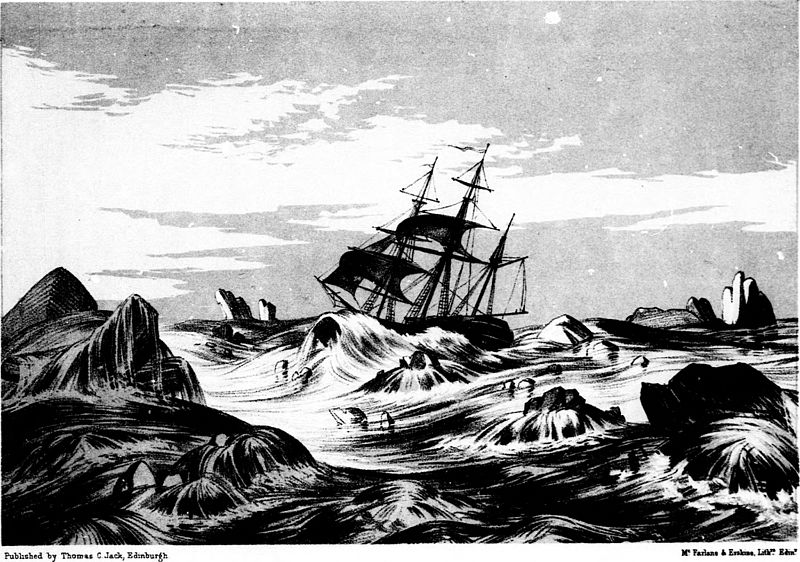

What happened after that is a matter of speculation. It is thought that the winter of 1845-46 was spent on Beechey Island in Nunavut, Canada. The two ships became stuck in the ice just off King William Island some time in September, 1846. They never got free.

The Search Begins

By early 1847, Franklin’s wife was growing increasingly concerned at the fate of her husband. Two summers had come and gone, which was the length of time that Franklin had told her he would be away. A naval officer offered to lead an expedition to search for the two ships but the admiralty replied that they had

‘unlimited confidence in the skills and resources of Sir John Franklin’.

As a concession, however, the admiralty did offer a reward to any whalers who could report any information about the progress of the expedition through Lancaster Sound.

Meanwhile an old friend of Franklin’s by the name of John Richardson made his own plans to mount a search party. He knew that the expedition’s food resources would run out in the summer of 1848. He planned an overland journey to the sea between the Coppermine and Mackenzie rivers. This was in the case that Franklin had made his way down the North American coast. Teaming up with a group of men from the Hudson’s Bay Company, Richardson headed down the Mackenzie River to Coronation Gulf in the summer of 1848. They found nothing.

Back in England, the Admiralty was starting to get worried. With no news of the Erebus and Terror by the autumn of 1847, they prepared to send out their own search parties. In January, 1848, two ships set out – the HMS Plover under a Captain Moore and the HMD Herald under a Captain Kellett. They headed for the Bering Strait to explore whether or not the two ships had become stuck near the western exit to the Strait. Two more ships, the Enterprise, under Captain John Ross’ headship and the HMS Investigator under Captain Bird headed out in June, 1848 to go into Lancaster Sound from the east in an attempt to follow Franklin’s tracks.

These moves were not enough for Jane Franklin. She wrote letters to the US President and the Russian Czar asking them to help in the search operation. She also set a larger reward for whalers than had the Admiralty. She even made plans to buy her own ship and commission her own expedition.

Hope was raised when the captain of a whaling ship reported that the Inuit Indians had spoken of four ships that were frozen in the ice in a channel south of Lancaster Sound. But when the Investigator and Enterprise returned having seen nothing in that area, the claim was dismissed.

Further searches were sent out by the Admiralty in 1850. The HMS Investigator and the HMS Enterprise set out again, this time to search both ends of the Northwest Passage. They joined the Plover and Herald which were still searching. Four more naval ships were sent to Lancaster Sound. The ships had balloons onboard that were let loose over the ice with notes attached to tell the missing men, if they were still alive, that help was on its way. Bu this time the crew would have sent five winters on the ice, so the belief that any of them were still alive was optimistic to say the least.

Private expeditions were also sent out to join in the search. A number of ships came together at the entrance to Wellington Channel between Cornwallis and Devon Islands. Finally, at a distance of about 230 miles from the entrance to Lancaster Sound from Baffin Bay they found something. At Cape Riley on Beechey Island the remains of the 1845-46 winter camp was found, along with the graves of three men.

Two American ships, Advance and Rescue, joined the search in 1850. They both got trapped in ice and drifted for more than a thousand miles out of Lancaster Sound, finally breaking free in 1851.

Lady Franklin was greatly buoyed when she received news that the winter camp had been founds. But she was crushed when the search party was aborted due to an early autumn freeze. She now directly contacted a Hudson Officer named William Kennedy, who agreed to mount a search with Lieutenant Joseph René Bellot of the French navy as second-in-command. This expedition set out in the summer of 1851 but found no traces of either the ships or any more camps.

Various searches continued through the spring and summer of 1851. As well as sending up message balloons, arctic foxes were caught and then releases with rescue messages attached to their collars. It was all to no avail and every ship returned without success.

A Wife’s Will

It was thanks largely to the constant lobbying of Lady Jane Franklin that the Admiralty continued to mount the search after six years. Lady Jane also stirred up public sympathy for the plight of her husband and his crew. The Admiralty agreed to send out a final search expedition in the spring of 1852. It was to be commanded by a Captain Belcher and consist of the Resolute and the Assistance, along with the steamers Intrepid and Pioneer. Assistance and Pioneer headed north up Wellington Channel while the Resolute and Intrepid headed west. A supply ship, the North Star, waited at Beechey Island.

Meanwhile, the HMS Investigator, which had set out in 1850, had not returned. Then, in April, 1853 an overland party from the HMS Resolute crossed Melville Sound and came across the Investigator trapped in the ice in Mercy Bay on the north coast of Banks Island. The men on board were starving to death. The rescue arrived just as the Captain was about to send out a desperate party on a one-thousand-mile trek to a Hudson’s Bay Post on the Mackenzie River in search of food.

Finally, in 1854, a Scottish Explorer by the name of John Rae discovered the fate of Franklin and his men. Rae was surveying the Boothia Peninsula on behalf of the Hudson’s Bay Company. It was there that he was given the story of the explorers by Inuit hunters. They story was that the ships had become stuck in the ice. The men on board couldn’t get free and so headed out on foot to find a way out. They had fallen victim to either starvation or the cold. The Indians also told Rae that some of the men had given in to cannibalism. Then, in 1855, another Hudson’s Bay man by the name of James Anderson cam across one of the boats from the Terror at the mouth of the Great Fish river. Some Inuit then showed him items that could have only come from the Terror and the Erebus.

In January, 1854 the Admiralty declared that the members of the expedition were to be assumed dead. Their wages would be paid to their relatives up until March 31st of that year. Lady Franklin would not accept this finding. But, after so long, she was now out on a limb. The London Times editor wrote that to continue the search would be . . .

wasting time upon a search for dead men’s bones.

It was now up to Jane Franklin to find the truth about her husband’s fate. She bought a schooner-rigged steam yacht called the Fox and put in command of it an experienced Arctic officer named Leopold McClintock. With 25 men, McClintock set out to cross Baffin Bay in the summer of 1857. However, the ship spent the winter drifting into the ice. In early 1858, the Fox entered Lancaster Sound and made its way toward Prince Regent Inlet past Fury Beach to a point near Bellot Strait. During sledging operations in early 1859, McClintock came across a group of Inuit who had items that must have belonged to the missing men, including snow knives. Then in a village not far from Matty Island, he purchased silver spoons and forks that were engraved with Franklin’s initials. The Inuit told him of a wreck that was four day’s journey away.

McClintock and his men headed to the south of the island. There they found the body of a man dressed in a steward’s uniform. Then a 28-foot boat was found, mounted on a sledge. The boat was laden down with clothing and other gear, including 20 kg of chocolate. There were also two skeletons onboard.

The Fate Revealed

At the northern tip of King William Island, the searchers found a campsite, which they named Camp Felix. Half way between the boat and the camp, two piles of stones were found, one to the north and the other to the south of a bay. Here were found single page records of what had happened to the crew.

The notes were both written by James Fitz James in May, 1847.

One of them read as follows . . .

April 25 1848 — H M Ships Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April, 5 leagues NNW of this, having been beset since 12th September 1846. The officers and crews, consisting of 105 souls, under the command of Captain F.R.M. Crozier, landed here in Lat. 69° 37’ 42” N, Long. 98° 41’ W. This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831, 4 miles to the northward, where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in June 1847. Sir James Ross’ pillar has not however been found, and the paper has been transferred to this position, which is that in which Sir J. Ross’ pillar was erected. Sir John Franklin died on the 11th June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

The Fox sailed back to England, having at least discovered the fate of the husband of their patron. When the items that they brought back from the condemned crew were displayed in Whitehall, it aroused great interest.

Leopold McClintock received a knighthood for his efforts in the search for Franklin and his men. Yet it would take more than a century and half before the two ships were finally found. In 2008 the Erebus was found. Eight years later the Terror was rediscovered to the southwest of King William Island. The ship was in pristine condition.

Sources:

Gillian Hutchinson: Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror Expedition

Scott Cookman: Iceblink: The Tragic Fate of Sir John Franklin

Jeffrey Blair Latta: The Franklin Conspiracy