In November 1887, the popular paperback magazine Beeton’s Christmas Annual introduced a new character to the world of crime fiction. His name was Sherlock Holmes. Along with his newly met friend and roommate, Dr. John Watson, Holmes moved about contemporary London, visiting sites and using conveyances familiar to his readers, as he tackled a mystery Watson called A Study in Scarlet. Though the story received positive reviews from some critics, it did not sell particularly well. Later published in a hardback volume, its sales too were disappointing.

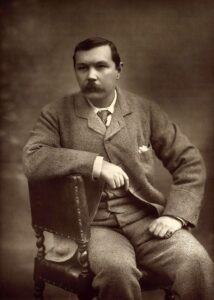

It was not the first work published by its author, a physician and ophthalmologist named Arthur Conan Doyle, who had written the novel in just three weeks. Doyle had by then been published in professional trades and fiction. Yet Holmes was the introduction of a character which transcended the literary world, not merely in crime fiction, but in all forms of literature. From that inauspicious beginning, Sherlock Holmes grew into international fame. He brought his creator great wealth and renown. He also brought his creator frustration to the point that Doyle attempted to kill the great detective, only to bow to public pressure to resurrect him.

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote prolifically on diverse subjects, yet today, with the possible exception of his 1912 science fiction novel The Lost World, he is remembered almost entirely for Sherlock Holmes. The Holmes stories, comprising 56 short stories and four novels, remain his legacy, while his other works are largely forgotten. It is a legacy that he feared and worked to prevent throughout his career. That career began in the slums in Edinburgh, Scotland. By its end, he had achieved some success in medicine, failed in politics, studied the occult and spiritualism, become a noted athlete, and published prodigiously. Yet, he is remembered for Holmes. It was a fate he feared and strove to avoid most of his life.

Early Years

Early Years

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on May 22, 1859, in Edinburgh. His father supported the large family by working as an illustrator until his steadily worsening alcoholism led him to be institutionalized. The family splintered for a time, to be reunited in the tenements, though not with Arthur. At the age of nine, Doyle, with the financial assistance of relatives, went to England to study, first under the Jesuits at Hodder Place, then at Stonyhurst College. In later life, he spoke of his early education in harsh terms, condemning the discipline applied by the Jesuit principles, as well as the course of study. In 1875, Doyle was sent to Austria to study at the Jesuit school Stella Matutina.

Doyle returned to Britain in 1876, studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh. He remained at the school until 1881. While there, he began to write, and in 1879, his first published short story, The Mystery of the Sasassa Valley, appeared in a local magazine. Featuring a South African valley dominated by a vengeful spirit, the story was published anonymously. During his studies, Doyle served as a ship’s physician on a whaling vessel. He later used his shipboard experiences in his writing. In 1881, he took his degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery, returned to the sea as a ship’s doctor for a voyage to West Africa, and finally, in 1885, received his degree as a Doctor of Medicine (MD). After a brief partnership in private practice with a former classmate, Doyle established his own practice in Portsmouth in 1882.

The Creation of Sherlock Holmes

Through hard work and word of mouth among his patients, Doyle’s medical practice gradually brought him sufficient income for him to live in reasonable comfort. One of his patients introduced Doyle to their sister, Louisa Hawkins. Though Louisa suffered from a then unknown illness, Doyle found her “amiable,” and they were married in 1885. Now with a wife to support, Doyle sold his first Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, in 1886. The second half of the novel’s settings in the American West were heavily influenced by the American novelist Bret Harte, one of Doyle’s favorite writers in his youth.

The character Sherlock Holmes, though, was based primarily on one of Doyle’s Edinburgh teachers, Dr. Joseph Bell, who demonstrated the powers of observation and deductive reasoning Doyle attributed to his detective. The relationship was so clear that Robert Louis Stevenson, a friend of Doyle’s and another student of Bell’s, wrote to the author, “…can this be my old friend, Joe Bell?” Holmes was not an overnight sensation, though he sold well enough to lead to a meeting with an American publisher, Joseph Lippincott. At a dinner in London’s Langham Hotel (a site later featured in several Holmes adventures), Lippincott entertained Doyle and another English author whose popularity was on the rise in the United States, Oscar Wilde.

Two novels were commissioned at that memorable dinner: The Sign of Four, a Holmes story from Doyle, and The Picture of Dorian Gray, from Wilde, the only novel Oscar Wilde ever wrote. The Sign of Four was moderately successful, but Doyle was growing restless in his practice and his writing success, which was limited for the most part to the Sherlock Holmes stories. The birth of his first daughter, Mary Louise (1889) served as another spur to Doyle. He went to Vienna, leaving his family in Portsmouth, to study ophthalmology, after which he opened a practice in London, in Wimpole Street. Louisa and Mary soon joined him there.

He did not thrive as an eye doctor in the bustling city of London, and a return to his Portsmouth practice seemed to him to be an admission of failure. Despite a desire to be seen as a serious historical writer, Doyle found little interest in his works, other than continued steady sales of his Holmes novels. Rather than approach his previous publishers, Doyle contacted the editors of the popular Strand Magazine. The first of the short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes appeared in Strand in July 1891, titled A Scandal in Bohemia. Five more followed, published in consecutive monthly editions.

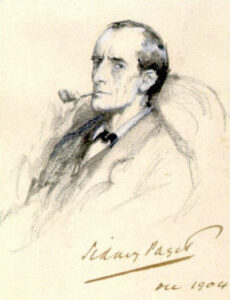

By the close of 1891, Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson, 221B Baker Street, and Arthur Conan Doyle were famous around the British Empire and in the United States. Strand Magazine commissioned a follow-up of six stories. Doyle turned his attention to writing full time. The stories in Strand Magazine, illustrated by Sidney Paget, produced the tall, spare, pipe-smoking icon, which has been the image of Holmes ever since.

Success, Acclaim, and Growing Frustration with Holmes

In the spring of 1891, Doyle decided to sell his medical practice, abandon medicine altogether, and pursue writing as his full-time vocation. Though it was the success of the Holmes character that allowed him to do so, he had no intention of focusing all of his efforts on stories of the great detective. He pursued other areas of literature, including historical fiction and tales of the supernatural. One of his earliest short stories, J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement, written in 1884, covered the story of the Mary Celeste, though in a fictional tale. Doyle wanted to continue with other stories in the same vein. However, his fans wanted Holmes, and the more the better.

Doyle placed Holmes in his London, which is to say, in the London and Empire of his readers. Londoners knew the neighborhoods Holmes knew, the restaurants and hotels, the theaters and museums, the railroad stations and schedules. They read the same newspapers Holmes read, attended the same concerts, and watched the same plays. To the readers, Holmes was a contemporary, a neighbor, a subject of the same monarch. His fans flocked to his Baker Street, its neighborhood, and the alleys and mews in which the fictional detective followed his quarry. They couldn’t get enough of him.

In 1892, Louisa gave birth to the couple’s second child, a son, whom they named Arthur Alleyne Kingsley Doyle. His growing family and wealth made Doyle increasingly restless. He began to cast about for ways to rid himself of the fictional detective that had led to his success. Having freed himself from his medical career to devote his full attention to writing, he felt the need to free himself from the literary hero he created. Doyle wanted to concentrate on writings about the supernatural, as well as historical fiction, and Holmes simply took up too much of his time.

Following the birth of his son, he traveled to the continent, visiting sites in Austria, France, Italy, and Switzerland. During the visit, he saw, in Switzerland, the waterfall at Reichenbach. Whether he had consciously already decided to kill Sherlock Holmes or if the idea was inspired by the falls is not known. He had signaled his intent to rid himself of the character, including writing to his mother, “I am thinking of slaying Holmes…” He had also complained to his editors at Strand Magazine that the character distracted public attention from his other works.

In an attempt to discourage Strand Magazine from publishing further adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Doyle demanded higher rates for the stories. To add to his frustration, the magazine willingly agreed to pay them. Despite the lucrative nature of the character and the stories featuring him, Doyle considered his other work to be more interesting and better in terms of his writing. In short, he believed Holmes had become a trap, preventing him from more serious and satisfying literary pursuits.

At any rate, in December 1893, Strand Magazine published a Holmes short story, the 24th in the series, titled The Final Problem. At the end of the story, Dr. Watson infers from the evidence he sees that Sherlock Holmes grappled with his archenemy, Professor Moriarty, on a ledge above the Reichenbach Falls, and both men had tumbled over the edge to their deaths far below. Public reaction to the death of Sherlock Holmes was immediate and negative. Strand Magazine’s subscription rolls plummeted nearly as quickly as had Holmes. Over 20,000 subscribers either canceled or failed to renew their subscriptions.

Doyle didn’t care. He turned his attention to writing short stories and novels, including those featuring a new character, Brigadier Gerard, a vain and pompous soldier in Napoleon’s armies. Gerard related the short stories himself, from the viewpoint of an old, retired soldier, reminiscing over his days as the greatest soldier and gentleman of all time. Eventually, he wrote 17 short stories featuring Gerard for Strand Magazine, as well as a play and a novel. Though the critics received them well, they did not generate the large fan base Holmes had.

Doyle traveled extensively during this period, to the continent, to what was then called the “East”, meaning Egypt, and to the United States for a lecture tour in 1894, appearing in over 30 cities. The worsening of his wife’s condition, finally diagnosed as tuberculosis, led him to travel to warmer climes in hopes it would ease her suffering, and she became his patient, rather than his partner. In 1897, Doyle met a young woman named Jean Leckie. They began a discreet affair, though Doyle insisted the relationship remained a platonic one while his first wife was alive.

The Author in Wartime and Politics

In 1900, Doyle, despite the misgivings of his family, volunteered for military service in the Boer War, offering his services as a physician. Though he served at Bloemfontein for just a few months, what he saw led him to produce two works on the war and Britain’s role in South Africa. He defended the British actions there and wrote The Great Boer War, a non-fiction account of the conflict published in 1900. At the time, the British public believed the war to be over, though, in fact, it dragged on for another two years.

On his return to England, Doyle stood for Parliament, and though he was not a practicing Catholic, his Jesuit education was exploited by his opponents. Depicted as a bigot loyal to the papacy, Doyle lost his campaign in Edinburgh in 1900. He ran again six years later, in Hawick Burghs, though he again lost. In between, Doyle was knighted in the 1902 Coronation Honors, receiving his award from King Edward VII in October at Buckingham Palace. From that point on, he styled himself Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

By then, Doyle had returned to Sherlock Holmes. In 1901, he published a new Holmes story as a novel, though it first appeared as a serial in Strand Magazine over the course of the year. Doyle deliberately set the story before the events at Reichenbach Falls, and moved most of the story outside of London to the moors of Devonshire. The Hound of the Baskervilles was well received by his readers, and though he continued to write prolifically on other subjects, Doyle finally bowed to the pressure from his readers and publishers and resurrected Holmes. The short story, The Adventure of the Empty House, appeared in Strand Magazine in October 1903, after first appearing in the American Collier’s the preceding month. In it, Holmes explains to Watson that he had faked his own death, and remained incognito to confound his other enemies.

Doyle continued to produce Holmes stories for the rest of his career, the last appearing in Strand Magazine in April, 1927. He experimented with the format from time to time, with Holmes relating a story on his own, without Watson making an appearance. But most retained his tried and true format, with Watson the loyal associate, as the two adventurers dealt with deadly assailants, hidden intent, and blundering policemen. Despite the success of the Holmes stories, Doyle continued to pursue other literary interests, writing multitudes of short stories and novels, which, though they sold well, continued to be dwarfed by Sherlock Holmes.

In 1906, Louisa died, passing away at home on July 4. The following year, Doyle married Jean Leckie on September 18, 1907. His children from his first marriage and his new bride moved into the Sussex mansion he had helped design, which he named Windlesham. It remained his home for the rest of his life, though he maintained apartments in London for his use during extended stays in the city. His second marriage was a happy one, and Jean and Sir Arthur had three children together. Following his second marriage, Doyle’s literary output slowed, though it was still prodigious. Devoted to his family, he brought them along on his many travels whenever possible.

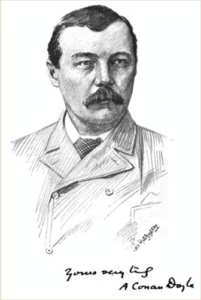

He continued to invent new characters and build series around them, including Professor Edward Challenger. Challenger made his first appearance in a science fiction/fantasy novel, which Doyle published in 1912, The Lost World. The novel featured a previously unknown South American plateau populated with dinosaurs and early hominids. Doyle provided Challenger with a temperament the opposite of Sherlock Holmes, and featured the character in three novels and a pair of short stories. He also posed for a portrait of Challenger, which he wanted Strand Magazine to run with the serialized version of The Lost World. The magazine demurred, though the photo was used in the first hardbound edition of the book in 1912.

The Avid Sportsman and Traveler

Throughout his life, Arthur Conan Doyle was what was known in his day as an avid sportsman. He was a devotee of boxing, played cricket, enjoyed golf, befitting of a Scotsman, and was an early proponent of the sport of bodybuilding. An amateur boxer, he turned down an invitation to referee a heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in 1910. The fight was held in Reno, Nevada, and Doyle excused himself based on the distance he would have had to travel.

Yet he loved to travel, in the company of his family, and made numerous excursions by ship and train to the United States, Canada, and the continent. He also became an early supporter of the automobile and loved to drive his increasingly powerful and fast cars. Unlike most gentlemen of his wealth and social standing, Doyle preferred to drive himself, rather than employ a chauffeur. Many of his sporting tastes appeared in Sherlock Holmes.

From the beginning, Sherlock Holmes exhibited extraordinary physical strength and skills in boxing and arcane wrestling holds. Noted fighters appeared in several Holmes adventures; Holmes introduced himself as a bare-knuckle boxer to another fighter in The Sign of Four. He credited his escape from Moriarty above Reichenbach Falls to his knowledge of the Japanese science of wrestling Holmes called baritsu (The Adventure of the Empty House). The famed detective also expressed lively interest in horse racing, cricket, and other sports. All of these reflected the interests of his creator.

As events on the European continent led to the increased tensions that gradually erupted in the First World War, Holmes was drawn in, with stories reflecting his involvement with government offices. During the war, Doyle traveled to the Western Front, publishing articles and books which explained the fighting to his readers, often in a manner critical of British military leadership. In 1917, with the war raging, Doyle published his final collection of Holmes stories, appropriately titled His Last Bow. An introduction to the collection, purportedly written by Dr. Watson, assured his readers that Holmes was living in retirement. It was an aspect of life not shared with his creator.

The Growing Lure of Spiritualism

Another trait of Doyle’s that Holmes did not adopt was his creator’s growing interest in the occult. Tragic events during the war that affected him personally only served to increase those interests. Doyle’s first son, Kingsley, was wounded severely at the Somme and died of complications of pneumonia while being hospitalized for his wounds. In addition to the loss of his son, Doyle’s brother, Innes, his brother-in-law, and two of his nephews fell on the Western Front. Doyle felt the losses acutely.

Following World War I, he focused heavily on spiritualism, seances, and trance-writing, and he addressed these and similar subjects in his work. The tragedies he suffered during the war, as well as the death of his first wife, no doubt stimulated his interest. It led to the Church denouncing his works and to increased mockery in the British tabloid press.

His belief in life after death and the ability of some gifted psychics to span the distance between the living and the dead led to numerous articles, essays, and books on the subject, which he supported via lecture tours and speeches. It brought him considerable disdain from skeptics. A 1920 tour of Australia and New Zealand as a spiritualist missionary led to outright mockery in the press. Yet he pressed on, certain of his beliefs, even as psychic after psychic, many of whom he publicly endorsed, were revealed as frauds. HIs friendship with the illusionist Harry Houdini came to an end when the famed magician exposed several seances as frauds, and described the methods used by the purported psychics.

Throughout the 1920s, Doyle’s defense of spiritualists and psychic mediums isolated him from many of his former friends and colleagues and brought considerable ridicule on his writings. Doyle spent over a quarter of a million pounds in his mission supporting spiritualism. He continued to produce short stories, and one final novel featuring Sherlock Holmes, the final Holmes story appearing in 1927. By then, four novels and 56 short stories made up the Sherlock Holmes canon, a mere fraction of Doyle’s literary output. There were also several plays for the stage and for the motion picture camera.

Last Days, Death, and Legacy

On July 7, 1930, Arthur Conan Doyle died from heart disease while at home at Windlesham. He was 71. He had suffered several attacks of chest pains during the preceding autumn, when he undertook a tour promoting spiritualism in Europe. Exhausted by the tour, he began 1930 confined to his bed, only able to rise and sit in a chair for short periods. One day in the spring, he arose and went for a walk in his garden, where he was found clutching his chest with one hand and a crocus in the other. Returned to his bed, he lingered for a time before succumbing, with his family surrounding him.

His renunciation of Christianity raised complications regarding his burial. His funeral on July 11 ended with his interment in his own garden at Windlesham. After his wife Jean died in 1940, Doyle’s body was reinterred next to her in a churchyard in Minstead, New Forest, Hampshire. None of Doyle’s children had children of their own, and after the 1997 death of his daughter Jean Lena, no direct descendants of the prolific writer and sportsman remained.

Though he published over 200 short stories and magazine articles, 23 novels, 13 plays, four volumes of poetry, 10 full-length books of nonfiction, and 13 books on spiritualism, with an additional 10 pamphlets on the subject based on his lectures, he is remembered chiefly for Sherlock Holmes. As he feared during his lifetime, his great fictional detective overshadowed his literary achievements. Today, 221B Baker Street is a museum dedicated to Holmes and Watson. A statue of Holmes stands in Edinburgh, near the birthplace of his creator.

Additional exhibitions of the sitting rooms occupied by Holmes and Watson are in Switzerland and London. A Swiss museum dedicated to Holmes is located near Reichenbach Falls. The Portsmouth City Museum, located near where Doyle lived and worked early in his career, is dedicated to the author and his most enduring character. Even in death, Arthur Conan Doyle cannot be separated from Holmes and Watson, and the befogged London streets they prowled, urged on by the mystery they are determined to solve.

Numerous other writers have taken up the Holmes mantle, in film, television, novels, short stories, games, and other media. But for Arthur Conan Doyle, Dr. Watson, Professor Moriarty, Colonel Moran, the hellhound of the Devonshire moors, and all of the author’s other creations remain his legacy, forever entwined with literature’s greatest fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes.