Twenty-five thousand years ago one’s man’s spiritual journey was the beginning of one of the world’s seven religions — boasting 376 million followers today. He is simply called “The Buddha,” and he grew up the son of a king…sheltered from the realities of human suffering. When he finally learned the harsh truth, he left his family and set off on a path to understand life itself — first as a monk and then as a teacher.

Let’s take a closer look at “The Buddha”, Siddhartha Gautama on Biographics.

Early Life

The founder of Buddhism was a man named Siddhartha Gautama. He was the son a chieftain and believed to be born in Lumbini (modern-day Nepal) in the 6th century B.C. His father Śuddhodana (translating to, “he who grows pure rice”) presided over a large clan called the Shakya in either a republic or an oligarchy system of rule. His mother was Queen Māyā of Sakya who is said to have died shortly after his birth. The infant was given the name Siddhartha, meaning “he who achieves his aim.” When Siddhartha was still a baby, several seers with the power of supernatural insight into the future, predicted he would either be a great spiritual leader, military leader or a king.

Since Siddhartha’s mother died, he was brought up by his maternal aunt, Maha Pajapati. His father, hoping to steer Siddhartha in the direction of the throne, shielded him from religion of any kind and sheltered him from seeing human hardship and suffering. As such, he was raised in the lap of luxury and blissful ignorance where he knew nothing about aging, disease, or death.

At the age of 16, Siddhartha’s father arranged his marriage to a cousin, Yaśodharā, who was also a teenager. She gave birth to a son, Rāhula, some years later. Siddhartha is said to have remained living in the palace until the age of 29 when everything changed.

According to the story, one day Siddhartha travelled outside of the palace gates and he was deeply disturbed by the sight of an old man. His charioteer Channa explained to Siddhartha that all people grow old and that death is an integral part of life. This prompted Siddhartha to secretly venture outside the palace on more trips. When leaving, it was said that, “the horse’s hooves were muffled by the gods” so as to prevent the guards from knowing of his departure. Outside the gates on these trips he encountered a sick man, a decaying corpse, and a homeless, holy man (also known as an ascetic). Channa told Siddhartha ascetics give up their material possessions and forgo physical pleasures for a higher, spiritual purpose.

After witnessing the reality of human hardship and suffering, Siddhartha had no interest in living at the palace. He left his wife and child to discover the true meaning of life, first through living as a traveling beggar, like the ascetics he saw on the streets.

Ascetic life

“The root of suffering is attachment.”

Siddhartha first went to the city of Rajagaha and began begging on the streets to survive. He was recognized there by the king’s men and offered the throne. He rejected it but promised to come back and visit once he attained enlightenment.

When he left Rajagaha, he met a hermit Brahmin saint named Alara Kalama. Kalama taught Siddhartha a form of meditation known as the dhyānic state, or the “sphere of nothingness.” Siddhartha eventually became his teacher’s equal and Kalama offered him his place saying, “You are the same as I am now. There is no difference between us. Stay here and take my place and teach my students with me.” But Siddhartha didn’t stay, and instead he moved on to another teacher, Udaka Ramaputta. Once again, he achieved high levels of meditative consciousness and was asked to succeed his teacher. Siddhartha refused the offer and moved on.

Through the practice of meditation, Siddhartha realized dhyana, a “state of perfect equanimity and awareness” was the path to enlightenment. He also realized that living life as an extremely deprived beggar, as he had done, wasn’t working. It had been six years, and he had eaten very little and fasted until he was weak.

Awakening

After starving himself for days, Siddhartha famously accepted milk and rice pudding from a village girl named Sujata. He was so emaciated, she thought he was a spirit there to grant her a wish.

Siddhartha, after having this meal, decided against living a life of extreme self-denial since his spiritual goals were not being met. He instead opted to follow a path of balance, known in Buddhism as the Middle Way. At this turning point, his five followers believed he was giving up and abandoned him.

Soon after he started meditating under a fig tree (now called the Bodhi tree) and committed himself to staying there until he had found enlightenment. He meditated for six days and nights and reached enlightenment on the full moon morning of May, a week before he turned thirty-five.

At the time of his enlightenment he gained complete insight into the cause of suffering, and the steps necessary to eliminate it. He called these steps the “Four Noble Truths.”

After his awakening, the Buddha met two merchant brothers from the city of Balkh in modern-day Afghanistan. The brothers, Trapusa and Bahalika, offered the Buddha his first meal after enlightenment and they became his first lay disciplines. According to some texts, each brother gave a hair from his head and these became relics enshrined at the Shwe Dagon Temple in Rangoon, Burma.

The Teacher

“I teach because you and all beings want to have happiness and want to avoid suffering. I teach the way things are.”

Legend has it that initially Buddha was reluctant to spread his knowledge to others as he was doubtful of whether the common people would understand his teachings. But then the king of gods, Brahma, convinced Buddha to teach, and he set out to do that.

The Buddha travelled to Deer Park in northern India, where he set in motion what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma by delivering his first sermon to the five companions who had abandoned him earlier. Together with him, they formed the first Buddhist monks, also known as saṅgha. All five attained nirvana, a state along the path to enlightenment yet not full enlightenment. They were known as arahants, meaning “one who is worthy,” or “perfected person.” From the first five, the group of arahants steadily grew to 60 within the first few months and eventually, the sangha reached more than one thousand.

The sangha traveled through the subcontinent, expounding the dharma. This continued throughout the year, except during the four months of the Vassa rainy season when ascetics of all religions rarely traveled. One reason was that it was more difficult to do so without causing harm to animal life. At this time of year, the sangha would retreat to monasteries, public parks or forests, where people would come to them.

The first vassana was spent at Varanasi when the sangha was formed. After this, the Buddha kept a promise to travel to Rajagaha, capital of Magadha, to visit King Bimbisara. During this visit, Sariputta and Maudgalyayana were converted by Assaji, one of the first five disciples, after which they were to become the Buddha’s two foremost followers. The Buddha spent the next three seasons at Veluvana Bamboo Grove monastery in Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha.

Upon hearing of his son’s awakening, Suddhodana sent, over a period, ten delegations to ask him to return to Kapilavastu. On the first nine occasions, the delegates failed to deliver the message and instead joined the sangha to become arahants. The tenth delegation, led by Kaludayi, a childhood friend of Gautama’s (who also became an arahant), however, delivered the message.

Now two years after his awakening, the Buddha agreed to return, and made a two-month journey by foot to Kapilavastu, teaching the dharma as he went. At his return, the royal palace prepared a midday meal, but the sangha was making an alms round in Kapilavastu. Hearing this, Suddhodana approached his son, the Buddha, saying: “Ours is the warrior lineage of Mahamassata, and not a single warrior has gone seeking alms.” The Buddha is said to have replied: “That is not the custom of your royal lineage. But it is the custom of my Buddha lineage. Several thousands of Buddhas have gone by seeking alms.”

Buddhist texts say that Suddhodana invited the sangha into the palace for the meal, followed by a dharma talk. After this he is said to have become a sotapanna. During the visit, many members of the royal family joined the sangha. The Buddha’s cousins Ananda and Anuruddha became two of his five chief disciples. At the age of seven, his son Rahula also joined, and became one of his ten chief disciples. His half-brother Nanda also joined and became an arahant. His wife, reportedly became a nun.

Throughout his life, Buddha encouraged his students to question his teachings and confirm them through their own experience. This non-dogmatic attitude still characterizes Buddhism today.

Buddhism

“You yourself must strive. The Buddhas only point the way.”

Buddhism is the fourth largest religion in the world and t is also one of the oldest, established in the 6th century B.C. in present-day Nepal, India. Unlike other religions, Buddhists do not worship a God. Instead, they focus on spiritual development with the end-goal of becoming “enlightened” — though not in the intellectual sense of the word.

In the Western world, enlightenment is most often associated with the 18th century European Enlightenment Period, a movement characterized by a rational and scientific approach to politics, religion, and social and economic issues. In Buddhism, the simplest explanation of attaining enlightenment is when an individual finds out the truth about life, and experiences “an awakening” where they are freed from the cycle of being reborn. Central to Buddhism is the notion that to live is to suffer, and everything is in a constant state of change. All Buddhists believe, unless one has become enlightened, they will be reincarnated again and again. Enlightenment can be achieved through the practice and development of morality, meditation and wisdom.

Four Noble Truths

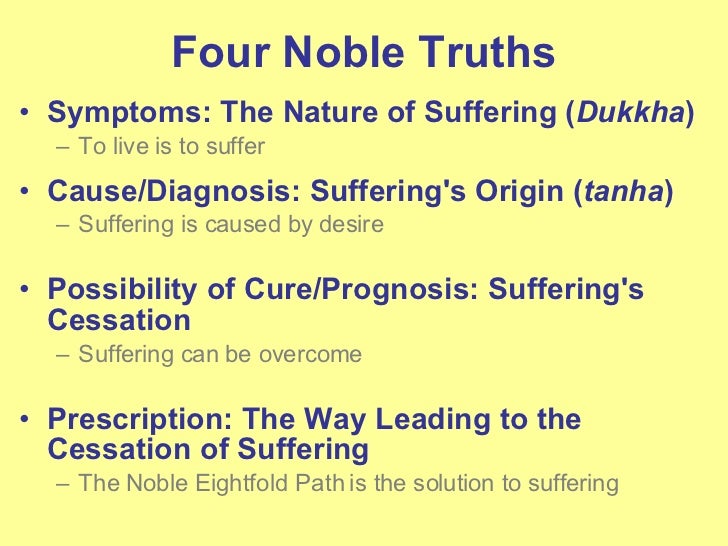

The Four Noble Truths contain the essence of the Buddha’s teachings. It was these four principles that the Buddha came to understand during his meditation under the bodhi tree. These are: The truth of suffering (Dukkha); the truth of the origin of suffering (Samudāya); the truth of the cessation of suffering (Nirodha); and the truth of the path to the cessation of suffering (Magga).

Suffering comes in many forms. Three obvious kinds of suffering correspond to the first three sights the Buddha saw on his first journey outside his palace: old age, sickness and death. But according to the Buddha, the problem of suffering goes much deeper. Life is not ideal: it frequently fails to live up to our expectations. Human beings are subject to desires and cravings, but even when we are able to satisfy these desires, the satisfaction is only temporary. Pleasure does not last; or if it does, it becomes monotonous.

Even when we are not suffering from outward causes like illness or bereavement, we are unfulfilled, unsatisfied. This is the truth of suffering.

The next noble truth is the origin of suffering. Our day-to-day troubles may seem to have easily identifiable causes: thirst, pain from an injury, sadness from the loss of a loved one. In the second of his Noble Truths, though, the Buddha claimed to have found the cause of all suffering – and it is much more deeply rooted than our immediate worries. The Buddha taught that the root of all suffering is desire, tanhā. This comes in three forms, which he described as the Three Roots of Evil, or the Three Fires, or the Three Poisons.

The three roots of evil are greed and desire, represented in art by a rooster; ignorance or delusion, represented by a pig, and hatred and destructive urges, represented by a snake. He taught more about suffering in his Fire Sermon, saying, a that is burning?

The eye is burning, forms are burning, eye-consciousness is burning, eye-contact is burning, also whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant that arises with eye-contact for its indispensable condition, that too is burning. Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion. I say it is burning with birth, aging and death, with sorrows, with lamentations, with pains, with griefs, with despairs.

The Third Noble Truth is Cessation of suffering (Nirodha). The Buddha taught that the way to extinguish desire, which causes suffering, is to liberate oneself from attachment. This is the third Noble Truth – the possibility of liberation. The Buddha was a living example that this is possible in a human lifetime. “Estrangement” here means disenchantment: a Buddhist aims to know sense conditions clearly as they are without becoming enchanted or misled by them.

Nirvana means extinguishing. Attaining nirvana – reaching enlightenment – means extinguishing the three fires of greed, delusion and hatred.

Someone who reaches nirvana does not immediately disappear to a heavenly realm. Nirvana is better understood as a state of mind that humans can reach. It is a state of profound spiritual joy, without negative emotions and fears. Someone who has attained enlightenment is filled with compassion for all living things.After death an enlightened person is liberated from the cycle of rebirth, but Buddhism gives no definite answers as to what happens next.

The Buddha discouraged his followers from asking too many questions about nirvana. He wanted them to concentrate on the task at hand, which was freeing themselves from the cycle of suffering. Asking questions is like quibbling with the doctor who is trying to save your life.

The Fourth Noble Truth is the path to the cessation of suffering (Magga). The final Noble Truth is the Buddha’s prescription for the end of suffering. This is a set of principles called the Eightfold Path. The Eightfold Path is also called the Middle Way: it avoids both indulgence and severe asceticism, neither of which the Buddha had found helpful in his search for enlightenment. The eight stages are not to be taken in order, but rather support and reinforce each other.

Death and Legacy

“I can die happily. I have not kept a single teaching hidden in a closed hand. Everything that is useful for you, I have already given. Be your own guiding light.”

According to the Mahaparinibbana Sutta of the Pali canon, at the age of 80, the Buddha announced that he would soon reach Parinirvana, or the final deathless state, and abandon his earthly body.

After this, the Buddha ate his last meal, which he had received as an offering from a blacksmith named Cunda. Falling violently ill, Buddha instructed his attendant Ānanda to convince Cunda that the meal eaten at his place had nothing to do with his passing and that his meal would be a source of the greatest merit as it provided the last meal for a Buddha. Mettanando and von Hinüber argue that the Buddha died of old age, rather than food poisoning.

The Buddha’s teachings began to be codified shortly after his death, and continue to be followed one way or another (and with major discrepancies) by at least 400 million people to this day.

There are numerous different schools or sects of Buddhism. The two largest are Theravada Buddhism, which is most popular in Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Burma (Myanmar), and Mahayana Buddhism, which is strongest in Tibet, China, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Mongolia. The majority of Buddhist sects do not seek to proselytise (preach and convert), with the notable exception of Nichiren Buddhism. All schools of Buddhism seek to aid followers on a path of enlightenment. “If with a pure mind a person speaks or acts, happiness follows them like a never-departing shadow.”

The Buddha’s place in history is one of influence that spans the globe and survives, thousands of years after his death. He is immortalized as a symbol, principal figure in Buddhism, and worshipped as a manifestation of God in Hinduism, Ahmadiyya Muslim Community and the Bahá’í faith.

Today, Buddhism is the dominant religion in many Asian countries, such as Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. Many forms of Buddhism exist, with Zen Buddhism enjoying considerable popularity in the United States. According to one 2012 estimate, approximately 1.2 million Buddhists live in America, with 40% of these adherents living in Southern California.