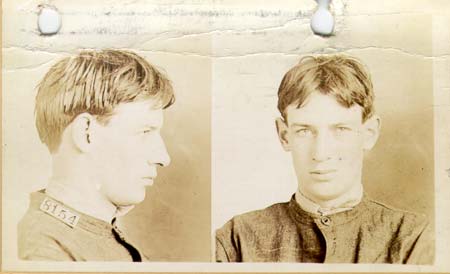

In his obituary, the New York Times called Robert Franklin Stroud “probably America’s most famous convict.” He rose to notoriety late in life, after author and former corrections officer Thomas E. Gaddis wrote a book about him in 1955 titled “Birdman of Alcatraz.” A few years later, this turned into a movie of the same name starring Burt Lancaster in the title role. This was a major Hollywood production, which proved popular with moviegoers and critics and received four Academy Award nominations.

Both the movie and the book were instrumental in shaping the persona of the Birdman of Alcatraz that the American public came to know and even admire. In both of them, Robert Stroud was portrayed in a positive, even heroic light. Here was a self-taught man of superior intellect with a lot to offer who did something bad once, but was ready and willing to make it up to society.

This view, although it turned Robert Stroud into a media sensation, did not line up with reality. At least, not according to the guards and inmates who actually knew him. One said that he “was not a sweetheart” like the Birdman in the movie and that “Burt Lancaster owes us all an apology.” Others said that the real Stroud was a “vicious killer”, or “a guy that liked chaos and turmoil.”

The doctor who did his official psychiatric evaluation in 1943 concluded that Stroud was a psychopath with an IQ of 112. Clearly, there is a lot more to the tale of the Birdman of Alcatraz than what has been publicized and today we will try to get the real story.

Early Years

Robert Franklin Stroud was born on January 28, 1890, in Seattle, Washington, to Benjamin Franklin Stroud and Elizabeth Jane McCartney.

Not much is known about his childhood. He had a younger brother and two older step-sisters from his mother’s previous marriage. Life at home was not a happy one because Ben Stroud was an alcoholic and an abuser and his children were often the target of his rage.

When he was 13, Robert Stroud had had enough of his father’s persecution so he ran away from home. He drifted from one place to another for a few years, before eventually making his way to the Alaska Territory when he was 18. At first, he found an honest job working on a railroad gang. This kept him on the move and he ended up in the town of Cordova. There, he met an older woman named Kitty O’Brien who worked as a dance hall entertainer and occasional prostitute. Stroud began serving as her pimp, although the exact nature of their relationship is still up for debate. Some say that it was strictly professional, while others believe that the two were romantically involved. Either way, they spent a lot of time together and, in 1908, they decided to relocate to Juneau which, back then, was a booming gold town.

It was here that Robert Stroud first started to show his violent nature. He became angry with an acquaintance of his, a bartender identified as Charlie Van Dahmer or Damer. The exact problem is uncertain. Some sources say that Van Dahmer beat up Kitty O’Brien, others that he refused to pay her after using her services, or maybe even both. Regardless, this was not something Stroud was willing to let slide.

He went to Van Dahmer’s shack to confront him. He was armed with a .38-caliber pistol. He waited for the bartender to arrive home and killed him with a shot to the heart. Afterwards, Stroud turned himself in at the city marshal.

His mother heard of what had happened and hired a lawyer to defend her son. They were able to strike a deal where Stroud would avoid a charge of first-degree murder with the possibility of the death penalty by pleading guilty to manslaughter. Both mother and son were hoping for a light sentence of only a few years in prison, but this was not to be. The federal judge who presided over his case was named E. E. Cushman. He was new on the job and eager to show everyone that he was hard on crime, particularly to those who used violence in his jurisdiction. He saw Stroud as the perfect man to make an example out of so, on August 23, 1909, Cushman sentenced him to the maximum of 12 years, to be served at the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary on the Puget Sound. Stroud didn’t know it yet, but he would never see life outside a prison again.

Life Behind Bars

Robert Stroud did not serve a lot of his sentence at McNeil Island. After his arrival, it did not take long before he developed a reputation with the guards and the other inmates of being an angry, dangerous man. On one occasion, he assaulted a hospital orderly whom he believed had reported Stroud to the prison administration for trying to obtain narcotics by using threats and intimidation. On another occasion, Stroud got into a fight and stabbed a prisoner who, allegedly, ratted him out for stealing food.

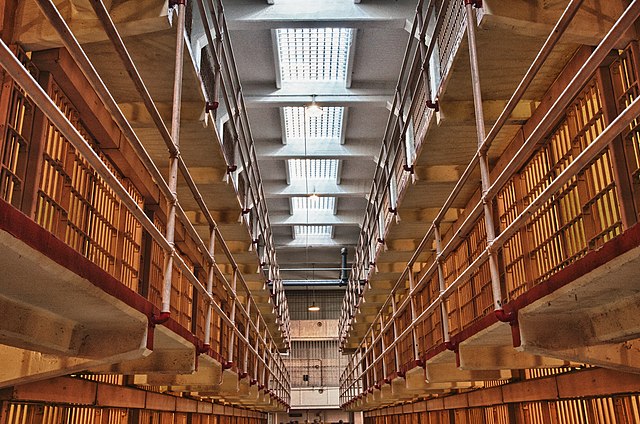

Credit: Yair Haklai – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

This attack earned Stroud an additional six months added to his sentence, but he would not serve them at McNeil. Instead, in 1912, Stroud and dozens of other inmates were transferred to a newer prison – the maximum-security Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas. Leavenworth would go on to become one of the most infamous prisons in the country but, at the time, it had only been opened for less than a decade and some of the cell blocks were still under construction. However, this move was necessary due to prison overcrowding.

Although Stroud had left school at age 12, he soon discovered that his time behind bars represented a good opportunity to continue his learning. He took various long-distance courses from the Kansas State Agricultural College and excelled at most of them, despite his third grade education. These included hard sciences like mathematics, structural engineering, and astronomy, but also spiritual courses like theosophy.

The progress Stroud was making was derailed in 1915 when he was diagnosed with Bright’s disease, an illness that causes chronic inflammation of the kidneys. Stroud had struggled with the pain and the other symptoms for years, but it finally reached a point where he became bedridden and, for a while, even feared that he might die. Eventually, he started to slowly recover, but he was left weakened and gaunt, not to mention that the pain was still there and was steadily turning Stroud into a more bitter and angry man.

Any hope he still had of ever walking as a free man went away the following year after he killed again. On March 26, 1916, Stroud attacked one of the prison guards in the mess hall and murdered him by plunging a butcher knife into his chest. That guard’s name was Andrew Turner and the exact circumstances behind his death are still somewhat unclear. Some sources which are more favorable to Stroud painted Turner as an arrogant bully who enjoyed taunting and exerting his authority over the inmates. Allegedly, Stroud became infuriated after being denied seeing his brother who came to visit him for the first time. He started lashing out verbally and Turner reported him which caused the inmate to lose all his visiting privileges. In turn, this led to the aforementioned altercation which resulted in the guard’s death.

Another version of the story also mentions Stroud as being enraged at not being able to see his brother. Turner, however, only did something trivial by telling the prisoner to stop talking in the mess hall, but this was enough to make him snap and kill the guard in front of over a thousand witnesses.

Escaping the Death Penalty

Obviously, Stroud was found guilty of first-degree murder. In his first trial, he was sentenced to death by hanging. Fortunately for him, his mother had, once again, hired a good lawyer to defend him. They immediately filed an appeal and managed to get the trial invalidated on a technicality. Stroud was safe, but only temporarily, as another trial was scheduled for the following year.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth Stroud was doing everything she could on her end to save her son. She wrote to everyone who would listen, trying to get them on her side and against the death penalty.

When the time came for the second trial, Stroud’s lawyer used the insanity plea as his defense, arguing that his client was mentally incompetent. He also claimed that Stroud acted in self-defense as Turner began attacking him with his club first.

On May 22, 1917, Robert Stroud was, once again, found guilty of Andrew Turner’s murder. This time, however, he was sentenced to life in prison and not the death penalty. Stroud was still not happy with the result, though, as he believed that his defense had been unable to present evidence which was critical to his case. He instructed his lawyer to file an appeal again, and the trial was, once more, invalidated and a new one scheduled for the following year.

Credit: Tim Wilson from Blaine, MN, USA – Alcatraz cell block, CC BY 2.0

The third trial did not go as Stroud was hoping. We’re not sure if it was because too much time had passed, or maybe annoyance that his client filed for another appeal, but Stroud’s lawyer lost interest in the case. When the hearing began, he failed to show up, prompting the judge to disqualify him and assign new lawyers to the defense. More than that, Stroud discovered that his lawyer had already negotiated with the prosecution without his knowledge, agreeing to enter a guilty plea for second-degree murder. This was probably the best he could have hoped for, but Stroud still protested the plea because it was done without his approval. Given the new circumstances, the judge decided to delay the trial for a few months.

In June 1918, the court proceedings resumed. Stroud was able to present all the new evidence and witnesses he wanted but, surprise, surprise, he was still found guilty of first-degree murder. Not only that, but this time he was sentenced to death again. Another appeal was filed by Stroud’s new lawyers and the Supreme Court ordered a temporary stay of execution while the case was analyzed. However, in November 1919, the Supreme Court not only upheld the decision, but also disallowed any further hearings on the matter. Robert Stroud’s execution was scheduled for April 23, 1920. At this point, those previous offers were probably looking pretty good.

After the third trial had concluded, there was just one person who still had not given up on Stroud – his mother. In order to save her son, Elizabeth had to find a way to appeal to a power greater than the Supreme Court. There was only one solution – Executive Clemency. She wanted to go straight to the President of the United States and ask to commute Robert’s death sentence.

At the time, the President was Woodrow Wilson, but he was bedridden following a stroke and his wife, Edith, handled many of his duties. She met with Elizabeth Stroud in person and, eventually, stopped the execution eight days before it was scheduled to take place.

Becoming the Birdman

The trials and appeals were over. Robert Stroud managed to escape the death penalty, but he was sentenced to spend the rest of his life in solitary confinement. He was placed in the so-called “Isolation Building” at Leavenworth where he had restricted contact with people and could not move around the prison grounds freely. That being the case, the warden did allow Stroud to continue his education and scientific interests.

The prisoner’s life took a significant turn for the better one day in June, 1920, while Stroud was out walking through the exercise yard. He had found what remained of a nest which got blown away during a storm. The nest was destroyed, but it still contained three live baby sparrows. Stroud decided to try and nurse them back to health and, thus, the Birdman of Alcatraz was born. As you are about to see, the “Birdman of Leavenworth” would have been a far more appropriate name for him, but I guess it didn’t have the same ring to it.

Anyway, Stroud brought the three sparrow chicks to his cell, improvised a nest and started feeding his new roommates. Some have described this event as Stroud finding a new lease on life as ornithology became his new passion. He read all the books on the subject that he could get his hands on. He learned how to properly care for birds and was allowed to keep canaries.

Fortunately for Stroud, the warden was initially pleased and even encouraged his new interest. It wasn’t long before the inmate started breeding his own canaries and even selling them to people who visited the prison. Over the following years, the Birdman’s aviary had become one of the main attractions at Leavenworth. At its height, Stroud packed in over three hundred canaries in his cell, keeping them in cages he made out of cigar boxes. His business lasted until 1931 when a new ruling said that federal prisoners were no longer able to conduct for-profit enterprises while incarcerated.

His day job may have gone away, but this did not dull Stroud’s enthusiasm for birds. He simply focused more on the theoretical side. Being in prison, there were obviously still a lot of things that Stroud could not obtain, so he improvised. He studied pharmacology and medicine so he could make his own remedies and antiseptics. When a bird died, he dissected it using his fingernails. He began corresponding with thousands of other breeders and bird experts and even started writing articles that were good enough to be published in journals.

One of the people Stroud corresponded with was a canary breeder from Indiana named Della Mae Jones who had been very impressed with the inmate’s avian know-how. Soon enough, she started visiting Leavenworth to see Stroud and the two even launched a business together selling his bird medicine. It did well, but it lasted only a short while before he was forced to give it up in 1931.

By this point, it was fair to say that the prison warden and the entire Federal Bureau of Prisons, for that matter, were growing tired of Stroud and his birds and would have liked to use this opportunity to get rid of them altogether. However, the Birdman did not take this decision lying down. Him and Jones (mostly Jones, if we’re being honest) began a letter writing campaign to raise awareness of his problem which resonated with many other breeders and bird lovers across the country. Jones obtained 50,000 signatures for a petition which she sent to the President of the United States. We’re not sure if the president was ever actually made aware of the issue, but all the added publicity was enough to get the Federal Bureau of Prisons to back off. They didn’t allow Stroud to make profits off his business again, but he could keep the birds, the scientific research, and equipment and was even moved to a bigger cell.

With the business side of his career gone, Stroud had nothing else to do but concentrate on the research. He compiled everything he learned about the death and disease of the birds he studied into a 60,000-word manuscript which he smuggled out of prison. In the outside world, Jones helped get it published in 1933 under the title Diseases of Canaries. Almost a decade later, he wrote and published Stroud’s Digest on the Diseases of Birds which was, more or less, the same book with some new and updated information.

The original title from 1933 was moderately successful and contained plenty of useful information, most of which is still relevant today. However, Stroud claimed that he had been cheated by his publisher and that he had not received any royalties from sales. He used the only weapon he had at his disposal – public opinion. He publicized the issue which prompted his publisher to complain to prison authorities who, again, began looking for a way of making the Birdman problem go away forever.

Allegedly, this was the first time that they tried to have him sent to Alcatraz, but Stroud managed to prevent it through a legal loophole. He learned that prisoners had the right to remain in Kansas if they were married to someone still living in the state so, later that same year, he and Della Mae Jones tied the knot.

Apparently, this enraged his mother. We cannot tell you why, exactly, maybe she believed that women were the source of all her son’s troubles, or maybe she held an unhealthy resentment for any other woman who was part of Robert’s life. Although she had been his strongest supporter for decades, Elizabeth Stroud completely turned on her son and even testified against him at his first parole hearing in 1937. Unsurprisingly, his parole was denied.

The problems came one after another in the years that followed. First, Stroud fell ill and, again, it was serious enough that it was thought he might die. He recovered, but a few years later his world changed forever. The prison board finally had the excuses they needed to get rid of him. On December 15, 1942, Stroud was woken up in the early morning and told he was being transferred to Alcatraz.

Welcome to the Rock

Allegedly, Robert Stroud only had ten minutes warning that he was being moved from Leavenworth. He had to leave behind all of his belongings which were sent to his brother. As for the exact reason, it wasn’t really explained in detail, citing merely a “serious breach of prison rules.” Supposedly, Stroud stood accused of using the special equipment he was afforded to make moonshine or shivs for the other inmates. Whether or not he actually did this, we’re not sure, but true or not, it allowed the Leavenworth officials to unload one of their problem prisoners.

Alcatraz had a much stricter set of rules. While Stroud was afforded some privileges like correspondence, access to the library, and even visitations, he was no longer allowed to keep birds. That’s right. Even though he is known as the “Birdman of Alcatraz,” Robert Stroud never actually had any birds during the 17 years he spent imprisoned there.

Instead, he kept on studying and writing. Supposedly, he learned multiple foreign languages during his time there, and he also completed two new manuscripts. One of them was simply titled Bobbie and it was an autobiography of his life before being incarcerated. The second one was called Looking Outward: A History of the U.S. Prison System from Colonial Times to the Formation of the Bureau of Prisons. This one proved to be much more problematic. Stroud wanted to publish it, but his request was denied by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The book was deemed libelous as it named multiple wardens and guards and the illegal actions they were allegedly involved in such as taking bribes or beating up prisoners. It was also considered obscene as it contained graphic sexual content.

Stroud filed a lawsuit but actually died before a decision was reached. Decades later, his lawyer took up possession of the manuscripts, but still couldn’t find a publisher. It wasn’t until just a few years ago that some parts of the book were published for the first time.

Back in Alcatraz, Stroud spent the first six years in segregation in D Block. For the next 11, he was confined to the hospital wing of the prison. He kept writing numerous petitions – to the president, to the Supreme Court, to the attorney general, to anyone who could help him – in order to get a release, but all his efforts failed. He tried to commit suicide once by overdosing on pain medication, but he didn’t take enough.

Robert Stroud was never able to get out of prison, but in his final years he got the next best thing. Due to his failing health, in 1959 he was transferred to the minimum-security Medical Center for Federal Prisoners in Springfield, Missouri. For a man who had spent most of his life in solitary confinement, this was an almost unreal experience. He could walk the grounds at his leisure. He had a park where he could spend his time. He saw his first TV program. Stroud later concluded that he saw more people and spoke more words in those last few years in Springfield than he did in the previous four decades of his life.

By this point, Thomas Gaddis had already published his book about him and work had begun on the movie. The Birdman of Alcatraz was one of the most famous criminals in the country. And yet, when Robert Stroud died on November 21, 1963, there were few mentions of him as he had the unfortunate timing of dying one day before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.