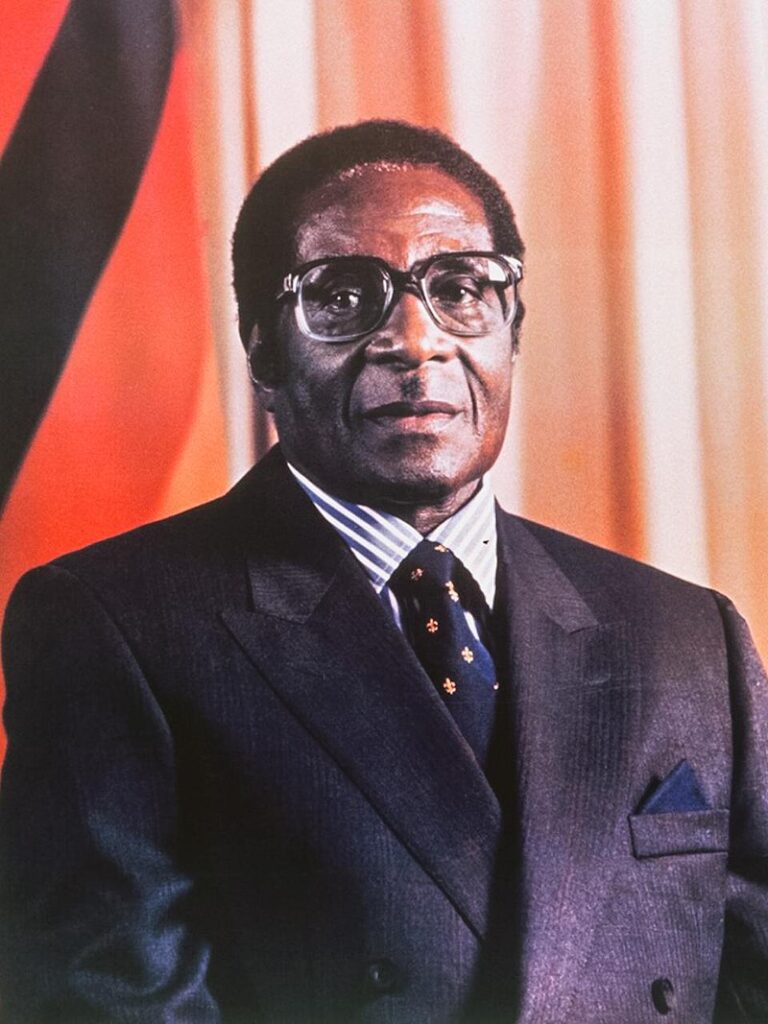

Robert Mugabe. Hailed as an anti-colonialist hero; despised as an autocrat and dictator. At the time of this video production, Robert Mugabe has just recently died, aged 95, after 37 years as the Prime Minister, and then President, of Zimbabwe. The news of his death had barely become public when many of you asked us to cover his life story and career. Here, we’ve obliged.

Robert Mugabe’s rise to power is a similar story to that of many rulers in the de-colonisation period. A story of a struggle for independence, a quest for national unity and societal development. And then: a gradual descent into autocratic rule, economic chaos and violence.

A Student and a Teacher

Robert Mugabe was born on the February 21, 1924 in Kutama, not far from Harare, now the capital city of Zimbabwe, but formerly the administrative centre of Southern Rhodesia, a recently constituted, self-governing British colony. At that time, political and economic power was firmly in the hands of the white minority, some 270,000 citizens who controlled the most fertile land. Conversely, six million locals were pushed into the colony’s driest regions, making a hard living from subsistence farming.

Young Robert was educated in a school run by catholic missionaries, and was by all accounts a studious and hardworking child. He later recalled that he enjoyed solitude, while looking after a herd of cattle in the sole company of a book. Robert’s father, a carpenter, abandoned the family when the boy was only 10 years old. That same year, Robert’s elder brother died, allegedly from a poisoning, which plunged his mother into a deep depression, interrupted only by violent mood swings.

In addition to looking after their farm and attending school, Robert had to look after his mother. He developed a strong bond with her, to the extent of being bullied for being a ‘mummy’s boy’.

Robert continued his studies into higher education: from 1950 to 1952, he attended Fort Hare Academy, in South Africa, thanks to a scholarship. In this period, he started to develop a political conscience, influenced by socialism and anti-colonialism, inspired by a desire for independence from British rule and by a will to break down racial divisions. Apartheid was becoming a tangible reality in Rhodesia and in neighbouring South Africa, and Robert found inspiration in Gandhi, Nehru, and the struggle for Indian self-rule.

Robert eventually graduated as a teacher, the first of many academic achievements: in later years, he would attain degrees in law, administration and economics.

The same year, 1953, saw Southern Rhodesia merge with the British protectorate of Northern Rhodesia. The resulting Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was still under British colonial administration.

Robert soon became ‘Mr. Mugabe’ to his students, after taking a series of teaching positions, first in the North of the federation – a territory which later became Zambia – and then in Ghana.

Mr Mugabe’s experiences in Ghana were life changing. On a personal level, he met and courted a colleague, Sally Hayfron. The two married in 1958. On a political level, Ghana was an eye opener for the young teacher: the West African country was already independent, a first taste of life free from colonial rule. He was deeply impressed by the policies of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, and his brand of ‘African socialism’.

This ideology embraced established aspects of socialism such as communal land ownership and planned economy, but fused them with private initiative, an acceptance of individualism, and a revival of pre-colonial African culture.

Mugabe returned to Rhodesia in 1960. Inspired by Krumah, and encouraged by Sally, he took his first steps into anti-colonial activism. He started campaigning against the discrimination of the black majority, which granted him an invitation to speak at a rally of the National Democratic Party, or NDP. The party leader, Joshua Nkomo, was impressed by the teacher and hired him as publicity secretary for the NDP.

Unfortunately, this alliance of two strong personalities was doomed to failure.

A Slow Rise to the Top

The leadership and membership of the NDP mirrored the make-up of the black population in Rhodesia, as it was divided into two main ethnicities: the Shona majority and the Ndebele minority. Nkomo, and most of the leaders, belonged to the latter. In 1963, the Shona clans rebelled against Nkomo, led by Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and by Mugabe himself.

The reverend and the teacher formed a breakaway faction, which became the Zimbabwe African National Union, or ZANU. The strong anti-colonial stance of the ZANU became a cause of concern for Rhodesian authorities. In 1964, they cracked down on the party leadership. Mugabe, Sithole and other activists were convicted of acts of sedition and sentenced to harsh prison terms that could extend up to 11 years.

The bitterness of incarceration was only made worse by news from outside: Mugabe’s only child had died in Ghana in 1965, and he had been denied leave to attend the funeral. During the same year, Rhodesia broke away from the British Empire, becoming an independent country, albeit without international recognition. Power remained firmly in the hands of the white minority.

The struggle of Mugabe, the ZANU and the NDP shifted in focus: the priority was no longer independence from the British, but rather, an established government led by the black majority in the country.

While in prison, Robert Mugabe made the most of this time by further advancing his education and preparing for total leadership. By the early 1970s, Mugabe was still playing second fiddle to Rev. Sithole, but trouble was stirring. Other party members, also incarcerated, accused the Reverend of cooperating too closely with white authorities, in exchange for prison privileges. Sithole was eventually ousted and Mugabe swooped in, becoming the head of ZANU.

In 1975, after the end of his prison term, Mugabe fled to Mozambique with the help of a white nun. There, he joined the ZANLA guerrilla force that had been harassing the Rhodesian government since 1964.

This was part of the Rhodesian Bush War, also known as the Zimbabwe Liberation Struggle. Let me tell you, this was a very complicated war, so get your notepads out.

On one hand, you had the Rhodesian Government, hampered by UN sanctions because of the lack of international recognition, but supplied in secret by the South African Government. On the opposite corner: the ZANLA, force, or Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, affiliated with ZANU, the party of Sithole and Mugabe. The ZANLA operated from Mozambique and was supported and supplied by China. In the third corner, there stood ZIPRA, the Zimbabwe People’ Revolutionary Army, operating from Zambia. Their backers were the Soviet Union and their political leader was Joshua Nkomo, who had now founded his new party – ZAPU.

Interesting to note: the ZANLA/ZIPRA dichotomy reflected the larger Sino-Soviet split, a major turning point of the Cold War. But let’s stay grounded in Rhodesia.

Mugabe did not actively participate in the fighting; his role was more political. He was the voice of the ideology who would motivate the fighters and swell their ranks through propaganda and recruitment. It is generally recognised that ZIPRA was in fact more of an active military force, while Mugabe’s ZANLA was more interested in sowing dissent and disobedience inside Rhodesia.

The complexity of the situation was thankfully reduced when Mugabe and Nkomo were forced by their followers to accept an uneasy alliance, the Patriotic Front.

The two leaders did not actively cooperate, but simply accepted each other’s existence and avoided infighting across their separate factions. While the insurgency versus the Rhodesian government continued, the stage was being set for a future conflict between the two rebel leaders. A CIA analysis noted how the two tried to upstage each other: Mugabe visited Havana in July 1977 to seek support from Fidel Castro, and possibly extend a hand to the Soviets. This worried Nkomo, who also flew to Cuba in November of 1978 to prevent the rival from snatching Soviet favors.

But the war was finally nearing its end. In late 1979 the British government mediated a peace deal between the Patriotic Front and Rhodesia. This agreement put an end to the war, sanctioned the independence of Zimbabwe and pushed the relatively obscure Mugabe front and centre on the International stage.

In early 1980 Mugabe returned from his exile to Harare and called for the first democratic election of the newly independent State of Zimbabwe. Mugabe was one of the candidates, of course, and he became Prime Minister with a 57% majority. One step at a time, the former teacher had reached the top.

The Rain and the Chaff

Was Mugabe’s victory a fair and transparent one, as ruled by British observers? Well, Mugabe had certainly built a following as a liberation hero and he could rely on the vote of the Shona majority. But it is also claimed that Mugabe’s guerrilla fighters intimidated many voters into picking the right candidate, by forcing them to attend indoctrination sessions, called ‘pungwes’.

Mugabe’s rule was marked by similar crafty methods. His first rival, Joshua Nkomo, was invited to join the newly formed cabinet, as Home Affairs minister. Generous, right? Well, yes, but actually, no. Nkomo’s powers were purposefully reduced: he was denied any authority over rural local government and, very importantly, over the Special Branches of the Police. Nkomo was a minister with no muscle.

This move was however in line with Mugabe’s public face: the face of reconciliation. The young State was rife with divisions. Mugabe vs Nkomo. Shona vs Ndebele. Black vs White. And yet the Prime Minister invited everybody to “Remain calm. Respect your opponents and do nothing that will disturb the peace. We must now all of us work for unity, whether you have won the election or not”.

Speaking of Unity, Mugabe was steering Zimbabwe into becoming a one-party state, under the ZANU-Patriotic Front, or ZANU-PF. And a one-party state could not tolerate opposition.

So, despite all the grand talk and overtures to former rivals, Mugabe was preparing to crack down hard on Nkomo and his followers in the Ndebele minority.

In August 1981, Mugabe invited military instructors from North Korea to train his crack troops, the Fifth Brigade. They would be known as Gukurahundi, a Shona phrase meaning:

“the rain which washes away the chaff”

This phrase would become the name of their more infamous operation, as we’ll hear in a minute.

In February 1982, a police inspection discovered a cache of arms hidden in a farm, owned by one of Nkomo’s companies. This was the perfect pretext to accuse Nkomo of plotting a coup, and to remove him from the cabinet.

Next, in January 1983, Mugabe unleashed his full-scale offensive against Nkomo’s followers, the Ndebeles living in Matabeleland, or western Zimbabwe. The Fifth Brigade, the Rain, swept through the region and washed away what Mugabe considered to be the chaff.

According to a report from Zimbabwe’s Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, the Brigade was responsible for mass murders, beatings and property burnings in the areas where Nkomo’s supporters lived. Within six weeks more than 2000 civilians had died, hundreds of homesteads had been burnt and many more thousands of civilians had been beaten. Most of the dead were killed in public executions involving between one and 12 people at a time.

“Villagers frequently report being forced to sing songs praising ZANU-PF while dancing on the mass graves of their families and fellow villagers, killed and buried minutes earlier.”

The operation in the west escalated into a full genocidal massacre: the atrocities continued until December 1987, when Mugabe and Nkomo reached another tentative reconciliation. By then, it is estimated that between 20 and 80 thousand Ndebele civilians had been murdered.

Executive President

While the atrocities went on in Matabeleland, Mugabe was consolidating his grip on power in Harare.

In 1985 Zimbabweans had been called to vote for a new Parliament. The white minority was constitutionally granted 20 seats in the Chambers and in that year, Ian D. Smith’s party won all 20 of them. Mr Smith had been the last white Prime Minister of Rhodesia, one who had vowed that the black majority would never rule his country.

Perceiving this as a threat, Mugabe sought to reinforce his power base as much as possible: so, he dissolved what little remained of Nkomo’s party and merged it with his own ZANU-PF.

With an unbeatable majority in Parliament, Mugabe in 1987 moved to legitimise his lone leadership. He managed to win a majority vote ratifying a change to the Constitution: this amendment eliminated the largely ceremonial President’s office, and created a new, much more powerful position for himself – Executive President. A title which combined the roles of Head of State, Head of the Government and Commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces.

In case some have not realized yet, Mugabe had just legitimised his own dictatorship over Zimbabwe. And yet, this was also his period of maximum popularity, both at home and abroad. Mugabe dedicated enormous slices of budget to education and healthcare, his policies managed to revive the economy and develop urbanisation in the Country. He even introduced anti-corruption laws, known as ‘leadership code’: this limited ZANU-PF cadres from owning more than 50 acres of land.

Zimbabwe was rapidly developing and Mugabe has also private affairs to take care of. In January 1992 his wife Sally died of kidney failure. In 1996 Robert Mugabe married his second wife, Grace Marufu, a former secretary in the presidential office and 41 years his junior. Mugabe and Grace had had an affair since at least 1990: their first child, a girl called Bona was in fact born on that year. According to him, Mugabe had asked Sally’s approval. Their marriage was childless and he wanted to sire a child before his own mother died.

Baby Bona could be counted among the so-called ‘Born-Frees’. These were the new generation of Zimbabweans born after the dissolution of Rhodesia. Many of them were ready to enter the labour market at the end of the 1990s. Having benefited from Mugabe’s increased spending on education, they were now realising that the country could not offer them the quantity and quality of jobs they were trained for. The Born-Frees lent their support to a new party, the Movement for Democratic Change, led by former labour leader Morgan Tsvangirai. Mugabe was about to face a new decade of turmoil.

Land grab

In February 2000 Mugabe called for a referendum to ratify a new Constitution, which would have solidified even more his grip on power. The President was expecting an easy victory, but the Movement for Democratic Change, more and more popular, gave him defeat in the polling stations.

Mugabe could not accept this and accused the MDC members of being lackeys of the white farmers, who had in fact openly financed the party.

The white minority of farmers and entrepreneurs made an easy target for the leader, who had always ruled on a platform of anti-colonialism and anti-capitalism. This minority was so small that it could hardly pose a threat – about 70,000 citizens over a total of 13 million. And yet Mugabe accused them of being dangerous agents of British colonialism.

Things got even worse for Mugabe when the June 2000 Parliamentary elections marked a relative victory for the opposition: the MDC did not win the majority of seats, but with a good 57 out of 150 they could leave a mark on legislation. It seems like 2000 was the year in which the President could not catch a break. Another group raised their voices in dissent: the veterans of the war of independence, theoretically great supporters of Mugabe, but now disgruntled as their pension funds had been embezzled by corrupt officials.

The veterans sought compensation by forcibly occupying farms, most of them operated by the white minority. Mugabe went with the flow, encouraging the vets to claim the lands as their own. From his perspective, this must have been an easy alternative to actually having to sort out an alternative pension fund!

Ironically, redistribution of land had been one of the priorities of Mugabe’s government after independence. And yet the issue had just sat there for decades. Neither Mugabe, nor the white farmers, not even the British mediators, apparently were interested in sorting it out.

In 2000, a full twenty years after independence, 4,500 white farmers still owned more than 50% of Zimbabwean farmland. It seems like the uprising of the veterans finally gave Mugabe the motivation to complete the land reform – in the worst possible way. Mugabe’s tacit consent to occupy the farms soon turned into active complicity. His supporters organised armed squads to invade the farms and chase away their white owners. Over the following two years, almost all the white-owned farmland had been redistributed to 300,000 black families. Many of these farms were assigned to competent commercial farmers, but many others went to reward Mugabe loyalists, who had no experience nor interest in working the land.

To use a Maoist analogy, this great agricultural leap forward eventually caused more problems than benefits. Many farms fell into disuse due to lack of modern equipment, fertilizers, efficient irrigation or just plain incompetence. Food shortages became common in the country, although the Government painted them as a consequence of drought.

Other leaders of the African Union started to pressure Mugabe into revising his policies or even retiring. But Mugabe would cling like a barnacle to his Presidential seat

“I am not retiring, I will never, never go into exile. I fought for Zimbabwe, and when I die, I will be buried in Zimbabwe, nowhere else.”

In 2008 a new season of elections proved to the world how tough could this barnacle be.

In March, opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai claimed victory in a presidential vote. But Mugabe claimed that there had not been an official vote count yet. This was delayed for weeks, until Mugabe’s officials announced that there hadn’t been a clear victor. The authorities scheduled a further round of voting. But in the lead up to the vote Mugabe’s security forces launched a campaign of intimidation against the opposition party, the MDC. This went as far as beating and killing opposition supporters. Tsvangirai had no choice but to seek refuge in the Dutch Embassy in Harare, from where he announced his withdrawal from the election. In the subsequent round of voting, Mugabe was the only candidate. Unsurprisingly, he won with 85% of the vote.

As he had done in the past, Mugabe sought to neutralise his opponent by absorbing him into the cabinet: Morgan Tsvangirai was sworn in as Prime Minister, although it was clear that the executive and military power was fully concentrated in Mugabe’s hands.

In the following 2013 elections, Mugabe, no surprise, was the clear winner again. They may as well printed polling cards saying “Who do you want as President? A) Robert Mugabe in a grey suit? Or B) Robert Mugabe in a blue suit?”.

It is clearly both, as a blue suit is not appropriate for evening social engagements. But the point is moot – by this time Mugabe had famously ditched formal suits for colourful outfits and loud headgear.

Whatever he wore after his victory, President Mugabe decided to end his arrangement with Tsvangirai, which returned to the opposition.

How to Ruin a Country

I am going to backtrack for a moment now to take a close look at Zimbabwe’s economy under Mugabe in the early 2000s. He had always been an autocrat, but at least in the 1980s and 1990s some of his reforms had ensured better standards of living for Zimbabweans. But after the ousting of the white farmers, Mugabe’s economic policies became farcically incompetent.

The collapse of Zimbabwe’s farming system had a negative impact on the rest of the economy. As food became scarce, its price increased, while farmers had less cash to spend on goods. Moreover, Mugabe had involved his military in Congo’s Civil War – a conflict so complex I will not even try to explain it.

As the government got deeper and deeper into debt, Mugabe’s central bank reacted in the worst possible way: quantitative easy. That is, printing money – to pay off debts and compensate the war veterans who had not benefited from land distribution.

As any citizen of the Weimar Republic could tell you, this can only create catastrophic inflation, which hit the rate of 231,000,000 percent. The currency had to be issued in notes as large as the 100 trillion Zimbabwe-dollar bill. In US dollars? That’s 40 cents!

The increase in prices had also affected housing. Many citizens in urban areas were unable to pay rent and so were forced to live in improvised shelters. Mugabe’s solution was simply to get rid of these shanty towns across Zimbabwe’s major cities. This was called ‘Operation Murambatsvina’, or “Drive out the rubbish” – a large scale Police operation which harassed, bullied and coerced 700,000 residents into moving to the countryside.

From 2008 to 2013, the coalition with Tsvangirai had some positive effects in curbing inflation. But since Mugabe reasserted complete control in 2013, he returned to his former inflation-inducing policies. How long could it last?

A Bloodless Correction

In the second half of the 2010s unemployment in Zimbabwe rose to 80 percent. The public health system, once the best in Africa, had collapsed. And yet Mugabe, Grace and their family appeared to spend lavishly on luxury goods and travel frequently to the Far East – both for shopping sprees and to seek treatment in expensive private clinics.

In 2014, apparently inspired by Grace, Mugabe removed his vice-president Joice Majuru and replaced her with staunch loyalist Emmerson Mnangagwa. This move coincided with the elevation of Grace to a leadership post in ZANU-PF, the ruling party.

It appeared as though Mugabe was setting the stage for Grace to succeed him as the new Executive President. The first lady was not a popular candidate, especially not amongst the military.

On the 7th of November 2017, shortly before new presidential elections, Mugabe fired his vice-president. The military saw this a sign of Grace’s impending appointment to the vice-presidency. One week later, the Generals occupied Harare, arrested the Mugabes and placed them under house arrest. It was clearly a coup, although military spokesmen described it as a ‘bloodless correction’.

Vice-President Mnangagwa was sworn in as President in the same month.

Robert and Grace were allowed to live in relative calm inside their 24-bedroom home in Harare and even to travel frequently to Singapore. Mugabe was being treated there for a long-term illness, apparently cancer.

Back in August 2019, President Mnangawa revealed that Robert Mugabe had been hospitalised in Singapore for the past few months. Then, on Friday the 6th of September Mnangawa announced that former President Mugabe, now aged 95, had died in Singapore.

“It is with the utmost sadness that I announce the passing on of Zimbabwe’s founding father and former President, Comrade Robert Mugabe. Mugabe was an icon of liberation, a pan-Africanist who dedicated his life to the emancipation and empowerment of his people. His contribution to the history of our nation and continent will never be forgotten.”

On that we can agree: his contribution of political violence, ethnic cleansing, corruption, and mismanagement will certainly not be forgotten.

Sources:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-23431534

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/robert-mugabe-longtime-zimbabwe-leader-dies-at-95

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/06/obituaries/robert-mugabe-dead.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-27519044