“Towards the middle of the 14th Century, a terrible plague struck at the people of the East and the West. It cruelly mistreated the nations, it carried away a great part of that generation, it swept away and destroyed the most beautiful achievements of civilization. It shattered the forces of Empires, snuffled their vigor, weakened their power to the point of total destruction. It was as if the voice of nature had then ordered to the world to humble itself, and the world had obeyed.”

These words were written in 1377 by Tunisian scholar and historian Abd-el Rahman Ibn Khaldoun. He was talking about the single greatest catastrophe in the history of mankind up to that point: the Black Death, which reached North Africa and Europe in the 1340s. But Ibn Khaldoun was not referring exclusively to that pandemic.

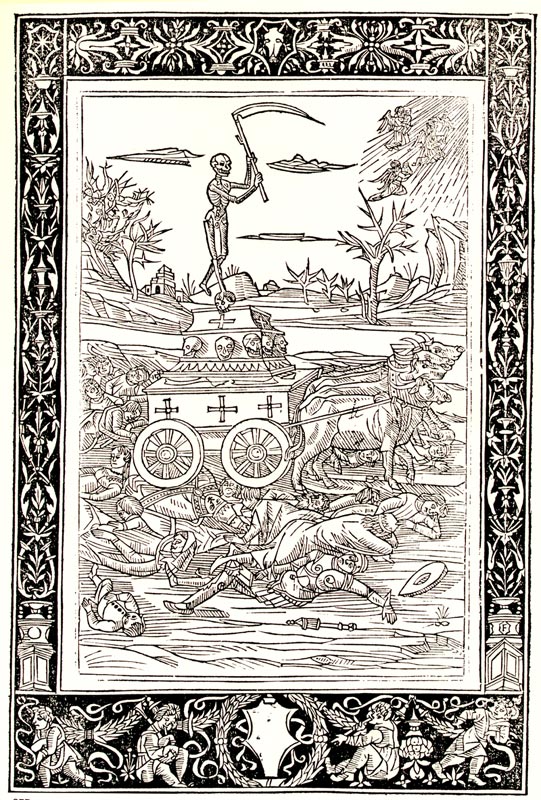

Modern accounts of the Black Death usually focus on the first wave but rarely cover its return to the shores of the Old World. But only a decade after the initial outbreak, inhabitants of Europe and the Mediterranean basin would again suffer from a second sweep of the grim angel. This time, the more innocent would fall. Black Death Redux became known as The Plague of Children.

Previously, on “The Black Death…”

The Black Death is the name we give today to the pandemic which killed between one-third and two-thirds of the World’s population in the first half of the 14th Century. The epidemic likely originated in Central Asia, or in China, in the early 1330s. It then spread to Europe, the Mediterranean and Africa, carried by caravans of merchants along the silk road as well as Mongol cavalry. By September of 1347, the Black Death appeared in Southern Italy, as an uninvited guest on merchant ships. From there, traveling mostly by sea, this mysterious disease conquered most of Europe and Africa, eventually subsiding in the early 1350s.

And when I say ‘mysterious’, I mean from the point of view of witnesses of that time. Contemporary historians, archaeologists, and medical professionals have identified the most likely culprit: The Black Death was an extremely virulent and infectious pandemic of bubonic and pneumonic plague, caused by a bacterium called Yersinia Pestis – or ‘Y. Pestis’. The bacteria used fleas as vectors, which in turn traveled on the fur of rats and other rodents. After infecting and killing their animal hosts, the fleas would attack humans.

If you want to know more about the Black Death you can watch our Biographics special from Halloween 2019.

Today, I will focus on the period immediately after the pestilence of 1347, and especially about the so-called ‘Second Plague’, ‘Second Pestilence’ or ‘Plague of Children’. This was the second outbreak, which ravaged Europe from 1360 to 1364. And I will take the occasion to review and contrast some theories which argue that these epidemics were not plague outbreaks and that Y. Pestis and its complementary fleas and rats were innocent.

But let’s stick to the chronology of events for the moment.

In the early 1350s, the Black Death had finally given some respite to Europe. More souls are swept away by the normal occurrences of the era: famine, endemic disease, the 100 Years War. The unseen Angel of death has laid down its broom – for the moment.

What type of society has arisen after the catastrophe? As I mentioned, as much as two-thirds of the population had died in an agony of fevers and swollen black buboes. This meant that fields and farms were empty. Some of the remaining survivors in the countryside abandoned their dwellings and moved to the cities looking for a fresh start. They were also looking to enjoy the incentives and benefits offered by city authorities: seeking to replenish their numbers, municipal leaders were keen to attract new residents.

Other survivors decided to remain in the countryside. Labour was now scarce, and peasants and farm tenants could now negotiate higher wages and lower rents.

The demographics of landowners had also changed. With entire families wiped out, large plots of land were left without anybody to inherit them … except for the Church, which used the aftermath of the Black Death to greatly increase its properties, wealth, and power.

Another consequence of the Black Death was a downshift in the nature of warfare. There were fewer men of fighting age, and especially fewer peasants that could be levied to raise armies. So, in the 1350s, feudal lords and monarchs had to rely more and more on companies of mercenaries. These private armies traveled frequently, either shifting theatre of operations, or simply switching sides. It can be argued that large numbers of traveling soldiers in unsanitary conditions may be a recipe for a pestilential disaster. But in the first half of the 1350s, no new epidemics were recorded in Europe … well, except for one unconventional sort — an unexpected outbreak of marriages!

Take the French town of Givry, 130km north of Lyon. Givry was hit the hardest by the Black Death in 1348. The town registers acknowledge zero marriages taking place that year. But in 1349? Forty-two lucky couples sealed their vows.

A similar situation was described in Britain by historian J.C. Russell. He argues that the Black Death in Britain killed only 20 percent of those aged 10 to 35, but exacted a much higher toll amongst their parents. So, the younger generations, having now inherited and become financially independent, were all too eager to marry!

A spike in marriages naturally led to an increase in birth rates. One could even say that humanity was bouncing back, or that nature was trying to compensate for the tremendous losses that the human race had suffered. I know that life in the late Middle Ages was no picnic – especially if you were French or English, slugging it out for decades on end.

The aftermath must have felt like a relief: after years of a Danse Macabre to the tune of a mourning bell, finally the giggles of children and nursery rhymes would fill the air.

Alas, it wouldn’t last long.

Return of the Darkness

The Black Death of 1347 had largely spared the lands of Bohemia and Southern Poland during its march of conquest. In 1352, the plague had reached the vast lands of Russia before apparently subsiding. In a way, Death had returned home, after starting its journey in Central Asia.

Five years later, the disease popped up again. In 1357, records show that a Second Pestilence had reached Prague, ravaging the city over the course of several outbreaks that lasted until 1360.

In 1359, evidence shows that the plague had crossed into modern-day Germany, with cases recorded in the city of Ulm and the region of Swabia. The contagion cut through Germany from East to West and crossed the Rhine into the Kingdom of France.

In 1360, the epidemic had reached the fair city of Avignon, in southern France, which had served as the residence of the Papacy since 1305. As you may imagine, such an important city was teeming with clergymen, bishops, aristocrats, and the best physicians that money could buy. One of them was Doctor Guy de Chauliac who left a precious testimony of his experience with the Second Plague, and the atmosphere of despair and paranoia that gripped his fellow citizens:

“Many were in doubt about the cause of this great mortality. In some places, they thought that the Jews had poisoned the world: and so they killed them. In others, that it was the poor deformed: and they drove them out. In others, that it was the nobles: and they feared to go abroad.”

The lynching of Jewish communities was, unfortunately, an all-too-common byproduct of this pandemic, as well as the 1347 outbreak. Even the Pope had called for Christians not to slay their fellow Jewish citizens.

But senseless death breeds panic; in turn, panic breeds violence, and violent crowds need a scapegoat. Jewish communities were perceived to suffer fewer deaths than Christian ones, and so it was easy to blame them as the cause of the plague.

These acts of violence, when recorded, could even be used by historians to trace the progress of the contagion. For example, French author Jean Glenisson was able to determine that the Second Plague had reached Poland in 1360 after finding Jewish Elegies commemorating the slaying of martyrs in Krakow.

Glenisson compared further Polish records with writings by De Chauliac in Avignon, and they all highlight the same conclusion: this Second Pestilence reaped victims across the societal spectrum, but it had a predilection for certain profiles of victims: young men over women, and members of the upper classes over the lower classes.

But most of all were child victims, aged 13 or younger. These were the children who had been born after the Black Death had disappeared, and who were now being struck down by this new Plague.

What would it have been like to be a parent in those days? Consider this: you have survived the single deadliest event in the history of humanity. You have risen from despair and found the strength to start a new life, and to create a new life. And only a few years later, that same invisible monster who has killed half of those you ever knew and loved… well, that monster returns and kills the young person who’s now given new meaning to your existence.

One year after Doctor De Chauliac had recorded his findings, the Plague had reached Paris. It was the summer of 1361. Here, chroniclers confirmed that children died by the thousands. They also noted that the illness killed scores of young men, in their late teens or early twenties, but spared their young wives. They described how the streets of Paris, half emptied, were strewn by silent shadows, gliding away with their eyes lowered to the ground: a city of widows, clad in black.

You may have started to spot a pattern here: Bohemia, Poland, young men, children, even the upper classes … areas and populations which had been spared the ordeal of the 1347 pandemic, were now succumbing to the Second Plague.

This trend was confirmed by the pattern of contagion in the Italian peninsula.

Deadly Vapours

In 1362 and 1363, the second pestilence crossed the Alps and made its return to Italy. Areas that had survived the first pestilence largely unscathed were now punished by the fury of the “new” contagion. In this case, the target was Milan; city authorities had successfully protected their population by enforcing a strict quarantine in 1348, but now they were taken by surprise. From Milan and Lombardy, the plague spread to the East, in the Venetia region, and then southwards, reaching Piacenza, some 70 km southeast of Milan. Here, an unnamed chronicler left a vivid description of the outward signs of the second pestilence:

“In some of the dying, an excretion coagulated in buboes under the armpits or on the groin. In others, pustules or abscesses formed around their heads, especially behind the ears. Others yet spat a putrid blood, which was a very bad sign. A burning fever suffocated all of them, after two or three days of manifesting.”

Our friend in Piacenza also explains how he may have survived:

“In patients who had developed buboes on the groin, if these tumours became softer … and the fever diminished … if the bubo was covered in a plaster of lard and mauve and then lanced with a hot iron and depleted of secretions, then the patient was healed”

This description is just one of the many cures which circulated at the time. The most widely reprinted was a treatise written by

“I, the Bisshop of Arusiens, Doctour of phisike,”

In other words: The Bishop of Aarhus, in Denmark, who also claimed to have studied medicine at Montpellier University, a renowned centre of medieval medical studies. Fun fact: two centuries later, Montpellier would be the alma mater of another famous plague doctor and prophet, Michel de Notre Dame, aka Nostradamus. We have a video profile about him, too!

So, what did the Bishop teach us about the Second Pestilence?

The Bishop believed that the disease was propagated by ‘venomous humours’ which entered the victim’s airways. To prevent this from happening, he recommended holding a loaf of bread or a sponge soaked in vinegar next to one’s mouth, for

“all aigre things stoppen the ways of humours”

He taught to look out for signs of warning which may alert to the incoming pestilence. These are: swarms of flies, shooting stars, comets, thunder and lightning coming from the south, and southern winds.

The venomous humors – or vapors – could be generated by any factor which may corrupt the air: a dead carrion, still waters in a ditch, or even a privy – aka, a toilet. These vapors may poison either the air or the ground. When both elements are corrupted

“an infirmity is caused in man”

This formidable physician explains why some people fall ill, while others are immune. According to him, bodies that are “more hot disposed” Will be an easy prey to contagion. By ‘hot disposed’, he meant people whose pores were more open than normal: this happened if they had an angry temper, if they engaged in hard physical labour, if they bathed too often or if they “abused them selfe with wymmen”

The Bishop addresses the question of person-to-person contagion. While a primary infection may be caused by humours, a diseased individual will develop boils and sores, which in turn will release toxic vapours infecting bystanders. He may have gotten the causes all wrong, but he nailed his next piece of advice:

“In pestilence time nobody should stand in great press of people, because some man of them may be infect … Also in the time of the pestilence it is better to abide within the house; for it is not wholesome to go into the city or town”

To get rid of the vapours, infected individuals should often change the chamber they sleep in and have their windows open to the North and East, but never to the South. Why the South? Because hot winds from the south will open your pores, of course!

As an added precaution against contagion, households were encouraged to purify the air by spraying vinegar and rose water.

Or by burning herbs such as bay-tree, juniper, wormwood and something called

“yberiorgam … ???”

Yes, us neither. Not a clue. If you have a clue, please let us know in the comments.

When it comes to curing the infected, the Bishop’s advice was to bleed the patients until they fainted,

“for a little letting of blood moveth or stirreth venom.”

Clearly neither the learned advice from Aarhus, nor from the writer in Piacenza, could work for all those affected. The plague took another leap in a southeasterly direction, reaching Bologna.

Here, the contagion was stubborn and unforgiving. The first cases were recorded as early as January 1362, and the citizens of this fair city continued to die for the next 13 months.

While Bologna was systematically decimated, the speed of travel for the second Black Death seemed to have slowed down. But it was only a temporary respite. In 1363, death moved to Tuscany, then central Italy. By June, it had entered Naples, its gateway to the rest of Southern Italy.

When Death kicked open the door to Naples, it had completed its invasion of the major port cities of the Mediterranean basin. Traveling merchants and sailors were efficient vectors of the plague: Barcelona, Crete and Damascus, among other port cities, had to endure the cruel cull.

The generalized mortality appeared to subside in Italy only in mid-1364, although it continued to haunt the canals of Venice for much longer.

Italian chroniclers and historians have observed an interesting point about the timing aspect of the second plague. It killed as quickly as the first one, after about five days from the appearance of the first signs, but its geographic spread was much slower compared to the original Black Death. That pandemic had blazed through the peninsula, South to North, in 10 months. The second one instead, had lingered on for almost three years, taking its time to lay ruin to depleted populations before marching on to another location.

The slower spread may be explained by the more selective nature of the killer of 1361. Most European chroniclers agree on the point that children and young men were the favourite victims of this plague. Young men especially were more physically mobile: by killing them, the pathogens also reduced their own chances to travel.

A slower spread, however, did not prevent the Plague of Children from reaching all the corners of the continent. Our next destination will be Britain, where we’ll take a look at the detailed records left by the bishops of Winchester.

“And I was left, feeling betrayed and stunned …”

A medieval text, the Polychronicon, tells us how the Second Plague outbreak began in London, during Easter of 1361. It then moved to invade the rest of Southern England. Like in France, Italy, or Poland, the pestilence laid waste among children, young men, and the wealthier rungs of society. Whereas nobles and clergymen had endured a mortality ratio of 4.5 percent in 1348, and 13 percent in 1349, nearly 24 percent of the upper classes were killed by the foul buboes in 1361.

But when it comes to the general death rate, all chroniclers and records agree that it was not as high as the one experienced during the Black Death. Approximately one-quarter of the population died during the second plague, which is still a horrifying figure out of context, but might be less than half the figure from only a decade earlier.

However, the second plague’s impact on society was equally devastating, if not more so. The population had not fully recovered, yet it was subjected to a second cull. The demise of the more innocent victims had a profound effect on the morale of those who were left behind.

The waste laid by the Second Plague in Britain is generally well-documented, but the records held in the diocese of Winchester offer a particularly detailed picture, as we have learned from an excellent paper by John Mullan of Cardiff University.

The bishops of Winchester oversaw 60 manors, spread over a large area which included six counties. The records left behind by the diocese give a detailed account of the demographics of the outbreak. During the 1348 Black Death, the Winchester lands had suffered a death rate of 48.8 percent, one of the highest in the British Isles, but the clergy had been largely spared.

But in 1361, priests, abbots, and nuns were not so lucky. Around 30 percent of them died, despite having a generally better diet and living conditions than the majority of the populace.

By looking at the inheritance deeds recorded in the six counties under the bishop, John Mullan was also able to confirm that the Second Plague had a predilection for male victims.

In 1349, almost 68 percent of all heirs were male. This was in line with previously recorded trends, and with customs of the age.

Skip to 1361, and now the majority of heirs were women: 61 percent! And amongst them, widows had the relative majority. This tells us that most of the victims were probably men in their 20s or 30s, whose children were too young to inherit. Or, even more likely, whose children had been sadly taken away by that Great Leveller, who did not care for young age or innocence.

The Plague of Children did not take long before it spread across Wales, Northern England, and Scotland. In manors across Britain, inheritance deeds and tax accounts provide a consistent picture of which demographics succumbed and which survived. But beyond the mere numbers, we would like to remember also the words of poets who were confronted with death.

Welsh poet Llywelyn Fychan recorded his experiences in a 1363 poem, ‘Haint y Nodau’, which could be translated as ‘The Infection of the Nodes’.

Llywelyn left us some vivid descriptions of the buboes, in verses filled with hatred for an incomprehensible enemy. To him, these swellings were like the

“pommel of a sword of swift strife” In the

“shape of an apple full of pain”

They were the

“bitter head of an odious onion,

a little boil which spares no one.

Smouldering like a red-hot coal,

a tiny thing which brings about man’s end”

The poet survived the pandemic, but his four children were not so lucky.

“Morfudd was taken,

Fair Dafydd was taken.

Ieuan, everyone’s cheery favourite, was taken.

With an unceasing lament, Dyddgu was taken.

And I was left, feeling betrayed and stunned,

barely alive in a harsh world.”

A harsh world indeed. The Second Pestilence eventually waned down, but the plague never really left Europe alone, returning for wave after wave. The disease returned in 1374, and then again in 1383, 1390 and 1400.

Every subsequent wave was overall less deadly than the previous one. And I stress ‘overall’: the total number of victims declined each time, but out of the total, the proportion of children increased.

Statistic from burial places in Tuscany show that in 1383, 88 percent of the plague victims were aged 12 or younger. A true slaughter of the innocents.

Following outbreaks appeared to be less cruel against children. But their combined effects caused a lasting decline in the population of Europe, which recovered to pre-1348 levels only one and half centuries later, in the 1520s.

A Changing Society

The profound demographic change brought about by the plague had lasting effects on the makeup of society. These were changes which, again, were well documented in England and may apply also to other parts of Europe.

According to historian Colin Platt, the toll exacted on young males caused a widespread shortage of labour, allowing for more women to enter the work force. Now, we know that more women had also become inheritors of wealth. The combined effect was that more women had become financially independent, which meant that they either decided to marry later, or not marry at all, leading to a decline in births.

The shortage of labour also led to an increase in wages and an abundance of cheap land, as many plots were now abandoned. This meant that those couples who did marry were less motivated to have children; in the Middle Ages, if you worked the land, an increase in children meant an increase in cheap labour. But this was not a requirement anymore, now that wealthier couples had access to cheaper land!

Another consequence of the labour shortage was a change in diet. In pre-plague years, most land was used to grow cereals. After the Second Pestilence, most arable plots were converted into woodlands and pastures, which are less labour intensive. The typical diet for peasants and farmers, which used to be cereal-heavy, changed to incorporate more meat and dairy products.

It is arguable, but we could stretch this dietary fact to its military conclusions: in the late 1300s every English village was able to train at least one big, extremely strong archer, skilled with a strong bow … the same archers who gave the edge to the English in the likes of the Battle of Agincourt, some decades later.

The subsequent waves of the plague also impacted the traditional feudal relationship between the peasants and their aristocratic landlords. Before the plague, peasants were more accurately described as serfs and paid rent to the local lord in cash, farm products, and labour. They had to ask permission if their daughter wanted to marry a ‘stranger’ from another village. They had to pay ‘heriots’, special taxes upon the death of a household member.

But by the end of the 14th Century, these serfs had morphed into either small land-owners themselves or free tenants, free of most previous obligations, except to pay a more reasonable rent in cash.

The ruling classes obviously tried to resist these changes by imposing laws aimed at establishing a status quo ante after the plagues. However, these were unpopular reforms that eventually sparked the peasant revolt of 1381, which was led by legendary leader Wat Tyler … but that’s another story!

The Final Conundrum:

Studies on the effect of the Plague of Children and subsequent waves raised some questions on the nature of the disease: was the Black Death actually an epidemic of bubonic plague caused by the Yersinia Pestis bacterium?

The implication of increased child mortality was the survival of older adults, who had been exposed to previous epidemics. This suggests acquired immunity. According to Prof Samuel Cohn of Glasgow University, among others, this is NOT a characteristic of the bubonic plague.

In the 19th and 20th Century, a pandemic of plague caused by Yersinia Pestis spread from Hong Kong to China and India, then to most coastal cities around the World. Medical professionals both then and now were able to observe that populations could be hit by returning waves of yersinia, and still suffer from the plague; in other words, they couldn’t develop an immunity. Strangely enough, rats actually could develop a resistance, which eventually lowered infection rates.

Speaking of rats, their most common parasites are the fleas known as Xenopsylla cheopis and Nosopsyllus fasciatus. In theory, these fleas were vectors for the plague bacterium, Y. Pestis. They thrive during periods of mild climate, like Spring and Autumn, while they become inactive in Summer and Winter. This seasonal pattern should influence patterns of contagion movement… but both the Black Death and the Second Plague did not follow these patterns and remained evenly lethal throughout the year.

Another piece of evidence against bubonic plague: medieval chroniclers never mention rats. The modern plague pandemic demonstrated how human contagion is usually preceded by large die-offs of rats and how rodents scurry out in the open in great numbers before dying. None of this is described during accounts from the 14th Century.

Critics of the bubonic plague hypothesis speculate that the Black Death and subsequent pandemics were caused by another disease. Maybe it was typhus, or smallpox, or even the flu. Maybe it was a yet unknown illness.

Supporters of Team Bubo defend their pathogen of choice by claiming that Y Pestis may have been spread by other parasites aside from Xenopsylla cheopis or Nosopsyllus fasciatus. Perhaps even human lice! And if medieval writers did not mention rats, this was because these rodents were so commonplace that there wasn’t any reason to include them in their works. Would a contemporary blogger from London spend any time writing about pigeons in Trafalgar square?

Proponents of the bubonic plague theory can call upon archaeology to support their claims.

In March of 2020, a mass burial of at least 48 individuals was exhumated near a medieval monastery in Lincolnshire, UK. The presence of coins with the image of King Edward III, and radiocarbon analysis, helped date these bodies as having died between 1327 and 1377.

In the tooth pulp of one body’s molar, the archaeology team of Prof Hugh Willmott found DNA sequences that matched those of the pathogen that killed those poor souls. And yes, it was Yersinia pestis.

Case closed, then? Not necessarily so. Traces of Y pestis have been found in medieval mass since at least 2002, but in many cases, contamination and methodology flaws have invalidated the results.

Regardless, there remains a central question to be answered: if recent outbreaks of bubonic plague did not generate immunity, why did this happen during the Plague of Children and the later waves?

An MIT paper from 2007 may have found the answer: maybe the medieval plague was a different strain of Y Pestis, in conjunction with a secondary infection that has yet to be identified.

For our part, we are not scientists, so we cannot give a definitive answer. What I can say for sure … it wasn’t caused by 5G.

Histories of the Plague

https://books.google.com/books/about/A_History_of_Bubonic_Plague_in_the_Briti.html?id=ATOlhaEvN3wC

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4139605

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23406498?seq=1

The records of the bishops of Winchester

https://orca.cf.ac.uk/3975/1/CHP8_Mullan.pdf

Critics of the bubonic plague theory

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/f/frag/9772151.0006.001/–black-death-bodies?rgn=main;view=fulltext

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2630035/

Supporters of the bubonic plague theory

https://www.jstor.org/stable/4139605?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

The Bishop of Aarhus and his medical advice:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42686/42686-h/42686-h.htm#Page_202

Mass Grave in Lincolnshire:

https://arstechnica.com/science/2020/03/mass-grave-reveals-how-black-death-impacted-rural-england/

Societal effects of the plague:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/24623408?seq=1

The Welsh poem ‘Haint y Nodau’:

https://pure.southwales.ac.uk/files/2759948/Death_and_Commemoration_in_Late_Medieval_Wales_DHale.pdf