“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings; Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

English romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote those famous words in 1818, to show that even the greatest of men and their mighty empires still fall prey to the ravages of time, destined to fade into oblivion. The name he chose was Ozymandias, which was what the ancient Greeks called the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II, alternatively spelled as Ramses or Ramesses.

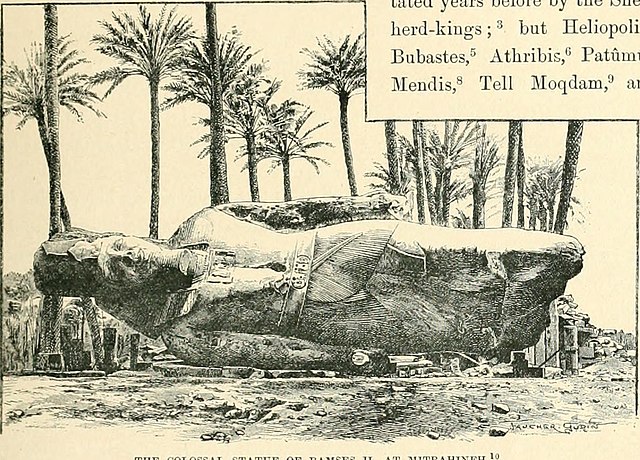

But Ramesses’s legacy was still alive in Shelley’s time and, if anything, it’s going even stronger today. All you have to do is take a walk through modern Luxor or Abu Simbel to be reminded that the pharaoh and his works still fascinate us 3,200 years later.

Ramesses’s almost unheard-of 66-year-reign as pharaoh gave Ancient Egypt its final glory days. One last golden age before it all started going downhill and the civilization never managed to regain its full strength ever again. It is clear to see why later Egyptians started referring to Ramesses II as the “Great Ancestor.”

Becoming Pharaoh

Ramesses II was born circa 1303 BC, into the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, arguably the most powerful dynasty of the New Kingdom period.

This lineage was founded by Ramesses I, our protagonist’s grandfather, who had served as vizier to the last pharaoh of the previous dynasty. He only reigned for a couple of years, but he set the scene for Egypt to enter a new golden age once his son, Seti I, took the throne. Seti had a good reign of 10-15 years and brought some much-needed stability to his kingdom, which was still in political and religious turmoil following the monotheistic revolution attempted by Akhenaten, which had only happened around 40 years earlier. But, of course, if you want to learn about that whole kettle of fish, check out our video on Akhenaten, the pharaoh branded a heretic.

Anyway, Seti I proved to be a strong leader at a crucial point for Egypt, as the nation was not only facing internal struggles, but also external ones, mainly in the form of its archenemy, the Hittite Empire. The Hittites had started out of the city of Hattusa, which is located in the middle of modern-day Turkey, but had successfully expanded south into Syria until they reached the borders of Egypt.

As pharaoh, Seti took a woman named Tuya as his Great Royal Wife, and they had several children together. Seti named his eldest son after his own father – Ramesses II.

We’re not going to go into Ramesses II’s own family tree for two simple reasons. One – there were just too many people. He had countless wives and concubines and fathered around 100 children. And two – a lot of them died before Ramesses, anyway, so they never really got the chance to do anything noteworthy. In fact, the king who ultimately succeeded Ramesses on the throne was Merneptah, his 13th son, who was already in his 60s by the time he became pharaoh. Just to put into context how long Ramesses’s reign truly was.

It has been suggested, although never definitively proven, that Seti made Ramesses co-regent in his last years as pharaoh. Seti died circa 1279 BC, thus paving the way for Ramesses II to become the third king of the 19th Dynasty.

The Battle of Kadesh

Ramesses was in his early 20s when he assumed power. Although he had received training and been awarded all sorts of fancy titles and positions since he was a child, he was still a greenhorn when it came to actual military matters. Even so, he showed himself to be quite eager to go on the warpath and actually garnered his most famous triumph just a few years into his seven-decade reign when he fought the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh.

Now, the city of Kadesh was very important to Ramesses, both from a strategic and a personal perspective. It was a valuable military asset because it was a fortified city and a major trading center located between the borders of the Egyptian and Hittite Empires at a time when the two powers often butted heads with one another. Remember, this was 3,300 years ago, and moving an entire army through the Syrian desert was a tricky proposition. Having a city like Kadesh on your side to serve as your base of operations could make the difference between victory and defeat, which is why both Egypt and Hattusa wanted to control it. Then, on a personal level, capturing Kadesh had been Seti’s greatest achievement. He was unable to keep it, though, and Kadesh fell under Hittite dominion again soon after the pharaoh left, so Ramesses may have wanted to finish what his father had started. Therefore, he immediately set to work building a grand army to drive the Hittites from Syria once and forever. In 1274 BC, only five years into his reign, the forces were ready and the omens were auspicious, so the Egyptian army marched on Kadesh.

The Battle of Kadesh is also special because, thanks to detailed inscriptions from both sides, it might be the most well-documented military conflict in all of ancient history. Ramesses had 20,000 soldiers on his side, split into four divisions: Amun, Re, Set, and Ptah. We don’t have exact figures for the Hittites, who were led by King Muwatalli II, but they were joined by 19 different vassals so, presumably, they weren’t hurting for soldiers, either. One notable thing about this battle was the large number of chariots that were used – each side deployed around 2,500, making this possibly the largest chariot battle in history.

Despite what the Egyptian inscriptions might say, the Battle of Kadesh was not a resounding victory for Egypt and Ramesses did not show himself to be some kind of Napoleon-level strategist. Quite the opposite, in fact. As we said, the pharaoh was still a young man, and his pride and naivety almost cost him not only the battle, but also his life.

Ramesses had received reports from a couple of passing nomads that the enemy, in pure astonishment of his mighty awesomeness, had begun retreating to Aleppo. Now, a more sensible person might be somewhat skeptical of such information, but not Ramesses. He saw it as the perfect opportunity to capture Kadesh, now that the bulk of its defense force had left. Therefore, he assembled his division of soldiers and began marching immediately, leaving the other three divisions to catch up.

You can probably guess what happened next – the Hittites were not in Aleppo, they were in Kadesh, waiting patiently, and the pharaoh just got suckered into their trap. Eventually, Ramesses realized that he was walking right into an ambush, but by then it was too late. The Hittites were getting ready to charge his camp, so the only thing he could do was to send word for the other divisions to hurry up and to hope that he could hold out until then.

Of course, we don’t know how much of what happened next is fact and how much is propaganda, but Ramesses apparently acted as a fierce and mighty warrior once the fighting started, rallying his scattered soldiers several times and personally leading his guard to repeatedly punch holes into the enemy ranks. The pharaoh managed to hold the opposing forces at bay until reinforcements arrived, at which point the tide turned and the Hittite army became overwhelmed. They tried retreating, but were caught between the Egyptian forces and the Orontes River, where they were either slaughtered or drowned. Curiously, King Muwatalli still had a large army within Kadesh, but he chose not to deploy it and instead fortified the city.

Despite standing victorious once the fighting was over, Ramesses still found himself outside the city walls looking in. He did not have the forces or supplies necessary to wage a long siege, so he had no choice but to scurry on back to Egypt. As to who won the Battle of Kadesh, that really depends on who you ask. The Egyptians, unsurprisingly, hailed it as a glorious victory and celebrated it on temple walls, stelae, and pylons all over the kingdom. The Hittites thought they won since, ultimately, they stopped the enemy from achieving their main goal of capturing Kadesh. Realistically, we should call this battle inconclusive, but its true ramifications would not become obvious for another decade-and-a-half.

Peace in Our Time

Ramesses’s feud with the Hittites was far from over, but they weren’t his only enemies. The pharaoh had lofty ambitions of bringing about a new golden age for Egypt, which included conquering lands that had not been part of his kingdom for decades, even centuries, such as Canaan. At the same time, he had to protect his own territory from invaders, such as the Sea Peoples.

Now, in case you’ve never heard of the Sea Peoples, they are probably one of the most mysterious civilizations of the ancient world. We do not have any firsthand information on them. They left nothing behind to be studied, but we do know of them through the prism of their enemies…and they had a lot of enemies. The Sea Peoples were a confederation of multiple seafaring groups who banded together sometime during the 13th century BC and started wreaking havoc on all the civilizations in the Mediterranean by raiding their coastal towns and cities – the Egyptians, the Hittites, the Greeks, and the Phoenicians all had to contend with the Sea Peoples. Today, we don’t really know where they came from or what, ultimately, happened to them, but the invasions of the Sea Peoples are considered an important contributor to the Late Bronze Age collapse, a dark period for many of the Mediterranean cultures.

As far as Egypt was concerned, it was Ramesses’s successors who mainly had to fight them off, but they proved to be a minor headache during his time, as well. The Kadesh Inscriptions, which were made to celebrate Ramesses’s victory at the Battle of Kadesh, casually mention that he had to fight off an attack from raiding sea pirates called the Sherden in his second year as pharaoh. Ramesses defeated the raiders by luring them into the Nile Delta and then pressed the prisoners into service, using them as mercenaries against the Hittites.

Speaking of whom, it was about time for that conflict to heat up again. A couple of years had passed since the Battle of Kadesh, enough time for both sides to regain their strength and get ready for round two. This happened around Ramesses’s seventh year as pharaoh. He took the Egyptian army into Syria again, but faced a similar scenario, one that his father had also encountered. Even if he did conquer new lands, he simply could not keep them. As soon as he left, those kingdoms either went independent again or fell under the hegemony of the Hittites, who fanned the flames of rebellion from afar and encouraged any kind of uprising against Egypt. Ramesses led yet another military campaign into Syria in his eighth regnal year, but even though he made it further up north than ever before, reaching a lost city called Dapur, it was still just “rinse and repeat” – when the pharaoh went away, the Hittites came to play.

As we said, Ramesses had ambitious goals he wanted to achieve. He couldn’t spend his entire reign trading border cities with Hattusa, especially when it became quite clear that neither empire was strong enough to gain a decisive upper hand over the other. Therefore, once that third Syrian campaign had ended, the feud between Egypt and Hattusa took a timeout, with the two powerhouses living side by side in a labored peace.

Their tense relationship culminated in 1258 BC, a landmark moment in history, when Ramesses II and Hattusili III, King of the Hittite Empire, signed the Treaty of Kadesh, the world’s earliest-known peace treaty. It happened during the 21st regnal year of Ramesses, 16 years after the Battle of Kadesh. The treaty was written on silver tablets, in two languages – Egyptian hieroglyphs and Akkadian cuneiform – and one copy was given to each civilization. The silver originals are long gone, but copies were made on clay tablets and some of them still survive to this day, with one replica even adorning the walls of the United Nations building in New York City. Tablets are nice and all, but the Egyptians liked to go big, so they also carved their version of the treaty into the temple walls at Karnak.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect was that the peace actually lasted. The cynics amongst you might have suspected that this was merely a stalling tactic, as each side waited for the perfect opportunity to pounce on the other when it was weak, but that did not happen. The Hittites had a new threat to contend with in the form of the Assyrians, so they were glad to get Egypt off their backs. The peace lasted for around 80 years, until the collapse of the Hittite Empire under invasions by Assyria and the Sea Peoples. Meanwhile, once Ramesses realized the futility of trying to control lands up in Syria, he focused his attention somewhere else.

The pharaoh’s efforts up north might have proved to be in vain, but there was still Nubia to the south and Libya to the west. In the past, parts of both regions had fallen under Egyptian hegemony and Ramesses was all about resurrecting the glory days of Egypt. Therefore, both made obvious targets. We know that Ramesses led military campaigns into each region, but not much more than that other than the fact that the pharaoh was successful in expanding his kingdom’s borders. It was quite a long way from the Battle of Kadesh where we knew the names and movements of each division. There are two likely explanations for this – one, most of the records were destroyed, or two, the pharaoh did not achieve anything that was worthy to put on a temple wall or stele.

It seems that Ramesses got most of his fighting out of his system in the first half of his reign. Of course, he didn’t know ahead of time that he would be pharaoh for almost 70 years, so in the immortal words of Danny Glover, maybe he was just getting too old for this sh…oot. Either way, Ramesses’s lasting legacy came not as a conqueror, but as a builder.

Ramesses the Builder, Can We Fix It

To put it simply, Ramesses the Great was one of Ancient Egypt’s most prolific builders, if not the most prolific, and we are counting the Old Kingdom pharaohs, who were obsessed with pyramids. The thing with Ramesses was that he built and repaired a lot of small-scale stuff – roads, storehouses, docks, temples, etc. – that was useful, but unlikely to feature on any Seven Wonders lists.

That being said, the pharaoh also had grand ambitions, and he showed them from the beginning of his reign by building an entire city to serve as his new capital – Pi-Ramesses. By all accounts, the city already existed in Ramesses’s time, most likely founded by his father or grandfather. Pharaoh Seti I even built a palace there to use as a little summer getaway, since Pi-Ramesses was located near the mouth of the Nile River, on its easternmost branch, whereas the Egyptian capital of Thebes was over 700 km south of the Nile Delta. But Ramesses decided to take this small settlement and transform it into a metropolis of great splendor, whose magnificence rivaled and even surpassed that of the old capital. He started by building four giant temples, each dedicated to a different deity – Amun, Set, Wadjet, and, most curious of all, Astarte, a Canaanite goddess adopted by the Egyptians as their own. Then he added residential areas, docks, storehouses, treasuries, canals, markets, military barracks, training facilities, and farms – everything needed to turn Pi-Ramesses into a thriving cultural, religious, and economic center.

One question that still puzzles archaeologists is what exactly made Ramesses choose that particular spot. Was it personal, practical, or propaganda, or all three? It could have been personal because young Ramesses grew up in that area so maybe he simply had a soft spot for the Nile Delta. It could have been practical, from a military standpoint. The pharaoh knew that the Hittites were going to be a major thorn in his side, so he needed a capital that was closer to the action, whereas Thebes was much further down south. And it could also have been a bit of clever propaganda on behalf of Ramesses, who wanted to position himself as the leader of a new golden age for Egypt. His new capital was located very close to the city of Avaris, which had served as the capital during the Hyksos period. The Hyksos had been the first foreigners to conquer Egypt, ruling as the 15th Dynasty for 100 years. They were eventually defeated by Ahmose I, who became the founder of the New Kingdom period. Since then, Avaris had become a legendary symbol of triumph over adversity for the Egyptians, so it would not be too surprising that Ramesses wanted to associate himself with that.

Unfortunately, we can only speculate as to how grand and opulent Pi-Ramesses looked at the peak of its power. It seems that the dynasties that followed were not too fond of the city and began ignoring it. Then, the 21st Dynasty moved the capital once more, this time to Tanis, and Pi-Ramesses was doomed to serve mainly as a quarry, plundered for all of its stone and other building materials, which were recycled and reused someplace else. The city was almost completely wiped off the map, to the point that Egyptologists excavated for almost 100 years until they found the location where it once stood, near the modern village of Qantir.

The good news is that not all of Ramesses’s building projects suffered the same fate. Many of them still stand in fact, at least partially, and represent some of the main attractions for visitors in Egypt looking to travel back in time to the age of pharaohs. First, there is the temple complex at Abu Simbel, originally carved straight into a solid rock cliff before it was entirely relocated during the 1960s. Like many other monuments built during Ramesses’s time, this one celebrated his victory at the Battle of Kadesh, which does make it seem like the pharaoh rested on his laurels a little bit.

Abu Simbel does show us that, of all the hundreds of wives and concubines that Ramesses had, his favorite was Nefertari, his first Great Royal Wife, since she was the only one who had her own temple, albeit much smaller in scale, next to that of the pharaoh. Nefertari does deserve credit for helping to bring peace between Egypt and Hattusa. Even though her husband liked to brag about his victory at Kadesh on every stone he found, we know that the battle was not as conclusive as he pretended to be and, in the long run, did little to stop the Hittite threat. It was the treaty that stopped the fighting, and Nefertari was instrumental in securing it because she was pen pals with the Hittite queen, Puduhepa. Clay tablets recovered from Hattusa revealed correspondence between the two queens, who referred to each other as “sister” and talked about marriage alliances between their two families to bring about peace between their gods and their husbands.

The Great Ancestor’s Legacy

Around 1249 BC, Ramesses celebrated his first Sed festival, a very important and ancient tradition that dated all the way back to the First Dynasty. It was a jubilee that was meant to honor the pharaoh’s long, continued rule, as well as renew his strength to keep him going. The first Sed festival was celebrated once a pharaoh reigned for 30 years and subsequent festivals were held every three years…ish. So you can imagine that even just one Sed festival was a big deal, but Ramesses celebrated 14 of them.

When he finally died circa 1213 BC, he would have been around 90 years old. His 66-year-long reign left Egypt as a regional powerhouse, both from a military and an economic point of view. External dangers such as the Sea Peoples threatened that hegemony but, ultimately, it was internal strife and power struggles that brought about the end of Ancient Egypt’s third and final golden age known as the New Kingdom.

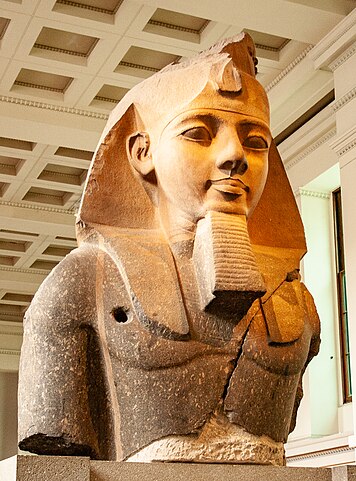

As far as Ramesses was concerned, he wanted to go out in style. Pyramids might have no longer been in fashion, but mortuary temples were the hot new thing during the New Kingdom. These buildings were constructed next to the royal tombs and were used to prepare the body of the pharaoh for the afterlife, as well as serve as cults of worship for them long after they were gone. Ramesses’s mortuary temple (or the Ramesseum as Egyptologists have dubbed it), was not only one of the pharaoh’s grandest building projects, but one of the greatest mortuary temples in Egypt, possibly outclassed only by that of Hatshepsut. The latter has the advantage of still standing, whereas Ramesses’s temple is mostly in ruins, prompting Percy Bysshe Shelley to write the words that opened today’s video.

But Ramesses’s story did not quite end there because his mummy was recovered and today is resting peacefully inside the Cairo Museum. Scientific analysis revealed that the pharaoh suffered for decades from very bad arthritis, as well as teeth problems and bad circulation but, realistically, for a nonagenarian from 3,000 years ago, that’s still pretty damn good.

We end our story with a final fun fact about Ramesses the Great – in 1974, he was flown to France for some vital preservation work. According to French law, however, all people flying into the country, alive or dead, needed a valid passport. Therefore, Ramesses became the first and only pharaoh to be issued a passport by the Egyptian government. Date of Birth: 1303 BC; Occupation: King (Deceased).