“Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.”

And he certainly did. That’s not only a quote from Pope Leo X, but also his philosophy. He had found the answer to life, the papacy, and everything, and it wasn’t 42, but rather money, money, money. Already born into the notoriously wealthy Medici family, Leo used his position of power to enrich himself to an insane degree so he could enjoy the finest things that money could buy.

Which he did…a lot…with mixed results, one could say. Although his spending helped give the world some of the most beautiful works of art from the Renaissance, his uncontrollable lust for power and riches caused a few rifts. This led to some warring, one assassination attempt, and one of the greatest schisms in the history of Christianity – the Reformation.

Early Years

Pope Leo X was born Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici on December 11, 1475, in Florence, which was back then not only an independent republic, but also one of Europe’s artistic, cultural, and economic centers. This was, in no small part, thanks to Leo’s family, the House of Medici, which was one of the most powerful and influential clans of the Italian Renaissance.

The family made big, big bucks in banking during the 15th century. In fact, under the ownership of Leo’s great-grandfather, Cosimo, the Medici Bank became the largest banking house in Europe. With that kind of money came some serious power and the Medicis were, in essence, the rulers of the Florentine Republic.

Unsurprisingly, little Giovanni, who we’re just going to call Leo from now on, had a privileged childhood, to put it mildly. He was the second son of Lorenzo de’ Medici, who was literally called Lorenzo the Magnificent, and Clarice Orsini, who came from another one of the great Italian noble houses.

You just can’t compete with that kind of pedigree. Leo grew up in a palace that was purposely built to be the tallest building in the area so everyone else would remember that none of them were quite as good as the Medicis. His walls were adorned with artwork by some of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, many of whom were sponsored by his relatives. As a teenager, Leo was friends with a young Michelangelo who practiced his sculpting in the Medicis’ gardens. Some of the richest and most powerful people in the world came to feast at Leo’s dining table. All the best tutors in Italy traveled to his palace to teach him. In other words, from the very second he was born, all of life’s circumstances worked in his favor to ensure that Giovanni de’ Medici would become someone of great importance.

Older brother Piero de’ Medici, later known as Piero the Unfortunate, was destined to be the heir and carry on the family business. However, as his name might suggest, things didn’t quite work out for him, and he and his family were exiled from Florence just a couple of years after assuming power from his father. Ultimately, it was up to little brother Leo to put the Medicis back in control of Florence, but we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves.

From birth, it seemed that Leo was destined to become a clergyman. Supposedly, his mother had a dream the night before he was born that she gave birth not to a baby, but to a docile lion. We’re not expert oneirocritics here at Biographics but, apparently, that meant that he was supposed to join the clergy. An oneirocritic is someone who interprets dreams, by the way, and yes, we had to look that up. In deference to his mother’s dream, Giovanni de’ Medici later adopted the papal name of Leo.

Life in the Church

With his career already planned out, Leo took part in his first important religious ceremony at age six when he received his tonsure. That’s when they give you the Friar Tuck haircut and shave your head apart from a band of hair around the noggin, as a symbol of humility and dedication to the church. Although, when you were a Medici, you didn’t really have to work that hard to show your dedication.

The following year, in 1483, Leo was made the abbot of Font Douce in France. He was put in charge of a monastery even though he was seven years old. And then another two in Italy – Passignano and Monte Cassino. Over the next few years, Leo held 27 separate offices, even though he was still too young to get into an R-rated movie. He didn’t have to actually do anything, of course. Just sit back and get rich. Well…richer.

Then, in 1484, Innocent VIII became the new pope. He was friendly with the Medicis, so Lorenzo saw a golden opportunity to secure some fast advancement for his son. In 1488, he married his daughter Maddalena to the pope’s son. Now that they were practically family, what’s a “tiny” favor between relatives? In 1489, the 13-year-old Leo was made a cardinal of the Catholic Church. This was done in secret because, even back then, this kind of blatant nepotism might have pissed off a few people. And it was in name only since Leo still was not allowed to wear the cardinal clothes or attend the College of Cardinals because, again, he was 13. Instead, the pope made him actually do some work and sent him to Pisa to study theology and canon law.

In 1492, after three years in Pisa, Leo was old enough to return to Rome, don the clerical garb, and become an official member of the College of Cardinals, the group that advised the pope directly and, most importantly, chose a new pope when the old one died. You’ll be surprised to hear that Leo was the youngest member of the college. His father, Lorenzo de’ Medici, died in April of that same year, but not before writing his son a letter, warning Leo of all the pitfalls and dangers that awaited him in his new life in Rome. He wrote:

“There will be many there who will try to corrupt you and incite you to vice…You must, therefore, oppose temptation all the more firmly… You are well aware how important is the example you ought to show to others as a cardinal, and that the world would be a better place if all cardinals were what they ought to be, because if they were so there would always be a good Pope and, consequently, a more peaceful world.”

Spoiler alert: Leo did not take his father’s advice.

The Condensed Chronicle of a Cardinal’s Career

With his father dead, Leo returned to Florence to support his family, and also to show a unified Medici front now that his brother Piero was taking over all of Lorenzo’s responsibilities. Despite the fact that Leo was richer than Croesus and already held a high rank as cardinal, his position was still somewhat tenuous. He had just lost his biggest supporter, the man who did everything in his considerable power to ensure that Leo made it this far in the first place. And three months later, he would lose another important ally as Pope Innocent VIII shuffled off his mortal coil.

This meant that Leo had to return to Rome to participate in the 1492 papal conclave and elect a new pontiff. The grand lotto winner was Alexander VI, the infamous Borgia Pope, and who knows, maybe someone we will cover here at Biographics in the future. But it took four ballots before Borgia won the election and, if rumors are to be believed, he only achieved this through briberies and promises of mutual backscratching.

With that out of the way, Leo once again went back to his native Florence but things weren’t going too well there. Piero did not have his father’s soft touch when it came to diplomacy and ruling from the shadows. He preferred the iron fist approach and the people of Florence were getting fed up with that. After all, he was just some spoiled rich brat, he didn’t hold any official title.

Adding to the turmoil, in 1494 King Charles VIII of France invaded Naples. This led to the appearance of the League of Venice which formed to oppose him and included Florence. However, before that happened, Piero tried to sign a treaty with King Charles, more or less, pleading with him to leave Florence alone. This was the final straw for the Florentines who saw it as an act of cowardice. In November 1494, they revolted against Piero and ran him out of town. Leo barely escaped with his life, disguising himself as a monk to evade the wrath of the angry mob. For the first time in 60 years, the Medicis were no longer in charge of Florence.

Big brother Piero never got to return to Florence. He spent the next decade in exile and drowned in 1503 following the Battle of Garigliano, thus making Leo the new head of the House of Medici. Meanwhile, the younger brother used this time to live up to the Medici name by doing the two things that his family was known for – spending money and being a patron of arts and literature.

After six years in exile, the cardinal made his way back to Rome where Alexander VI was still pope, but not for long. Alexander died the same year as Piero and Pius III became the new pontiff. However, he died too, just 26 days after being elected, so by the end of 1503, Julius II had been chosen as the new pope.

This represented a turn in Leo’s fortunes because Julius was fond of the young cardinal, even though the guy seemed a bit confused about his job duties. He was head of the Catholic Church; the spiritual guide for millions of people, but what the pope really wanted to do was to cosplay as Julius Caesar, the man he named himself after. He rallied the Papal States against France and even personally led his troops at the Siege of Mirandola in 1511, earning himself the moniker of the “Warrior Pope.”

But, whatever, if the pope was itching for a good fight, then Leo was eager to please. In 1511, he entered the combat zone, only to be defeated at Ravenna in 1512 and taken prisoner by the French. Fortunately for him, his confinement did not last long. Shortly after, the Holy League formed by Pope Julius bested the French army and drove them out of northern Italy. This allowed Leo to don a disguise once again (this time of a soldier) and make his escape.

Leo might not have made a particularly effective soldier, but his enthusiasm was rewarded nevertheless. With France on the back foot, the pope decided that it was time for the Medicis to regain power in Florence, with a little help from Spain, a fellow member of the Holy League. At first, the Florentines resisted and, fortunately for them, their city was too nice to destroy. Instead, as punishment, the Spanish army sacked the nearby town of Prato, just to show them what would happen if they didn’t play nice. It really sucked for Prato, but Florence got the message nice and clear so, after 18 years in exile, the Medicis were welcomed back to the city.

Well, as a cardinal, Leo wasn’t officially allowed to rule over Florence, so little brother Giuliano was put in charge. This was on paper only, however, as everyone knew Leo was actually calling the shots. And this was only the beginning…

Pope Leo

Pope Julius II died on February 21, 1513, thus necessitating the College of Cardinals to gather once more and elect a new pope. At first, things weren’t looking great for Leo. For starters, he was suffering from a painful anal fistula and had to be carried into the Vatican on a special chair and operated on during the conclave. Then, during the first ballot, he only received one vote, making it seem like he had no chance of winning the papacy.

But things were not as they seemed. In fact, Leo had quite a few backers, particularly among the younger cardinals, but they chose not to reveal their support from the outset, instead voting for other candidates they knew had no chance of winning. Then a lot of secret backdoor shenanigans took place and, seven days later, the decision was unanimous. On March 19, 1513, the 37-year-old Giovanni de’ Medici was crowned Pope Leo X.

Everyone had their reasons for voting for Leo. Some genuinely believed he was the best candidate. Others wanted someone as different from the “Warrior Pope” as possible, and Leo, with his love of arts and literature, fit the bill perfectly. Some might have even been moved by the young cardinal’s dedication to his role despite his agonizing medical condition, or perhaps they felt that his illness meant that his tenure as pope would be a short one. And others were merely “persuaded” behind closed doors.

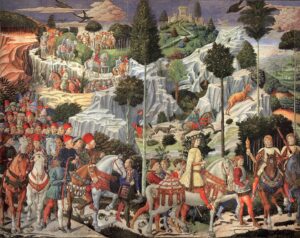

Whatever their motivation might have been, Leo was now the head honcho, and he celebrated in style with a lavish parade in Rome. All the houses along the route were decorated with laurels and expensive velvet cloths. Splendid new archways were constructed. The fountains spouted wine instead of water. As a giant procession made its way through the city streets, Leo was right at the end, riding a white horse under a canopy made of embroidered silk, draped in a jeweled cloak and the papal tiara. It was quite a sight to see and the celebrations were matched in Florence, where the people were now ecstatic that one of their own was the new pope.

Everyone was hopeful that the reign of Leo X would usher in a new golden age, but it didn’t take long for him to prove them wrong. From the beginning, Leo made it pretty clear that he wasn’t particularly interested in any kind of reform, even though many of Europe’s Catholics felt that the Church was long overdue. The pope liked things the way they were. For starters, he made sure his family was well taken care of. He appointed his cousin Giulio as the new Archbishop of Florence, while his nephew, Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici, became the Duke of Urbino, and also the new ruler of Florence once Leo’s younger brother passed away in 1516.

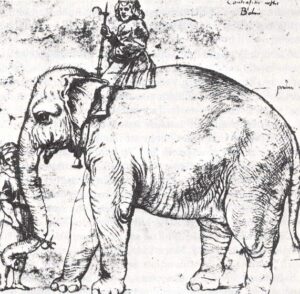

But this kind of favoritism was hardly unexpected. Leo’s biggest problem was that he liked to spend money…A lot of it. During his time, the papal household had almost 700 servants, more than any other pope who came before him. And his palace had to be furnished and decorated with the most luxurious, and expensive items that money could buy. And he loved throwing lavish feasts with exotic dishes such as peacock tongues or pies filled with live nightingales. And he wanted to maintain the family’s reputation of being patrons of the arts so he sponsored many famous Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael and kept them from turning to a life of vigilantism as ninja turtles. And he had a pet elephant named Hanno who is still buried under the Vatican’s Belvedere courtyard to this day. And, to give Leo full credit, he was also said to be generous with the less fortunate, donating over 6,000 ducats a year to the poor, sick, and homeless of Rome, where one ducat coin had about 3.5 grams of pure gold.

We’re not saying that Leo’s spending was all bad. Some good things did come of it. But it was out of control and, even as the pope and the head of the House of Medici, he still didn’t have the “infinite money” cheat code. So he turned to a tried & true practice that his predecessor tried to do away with – selling indulgences; basically, accepting payments to absolve people of their sins. If you were on the naughty list but didn’t have the time or disposition to pray, recite hymns, or any other kinds of repentance, just give the Church a lot of money and all was forgiven. Sure, this was a fast and easy way for Leo to refill his coffers, but it would come back to bite him in the ass in a big way.

Murder at the Vatican

In 1517, less than four years after he became pope, things started to take a serious turn for Leo. It began with the War of Urbino in January when Leo decided that his nephew, Lorenzo, should be the new Duke of Urbino. Quite annoyingly, there already was a Duke of Urbino – Francesco Maria della Rovere – and he wasn’t about to give up his spot just because the pope demanded it. So the two sides fought during the first half of the year and Della Rovere had the upper hand for most of the conflict. He only had to concede defeat because he ran out of money to pay his troops but, ultimately, it was a pyrrhic victory for Leo. It’s estimated that it cost him around 800,000 ducats and Lorenzo ended up serving as Duke of Urbino only for three years before he died suddenly at age 26 and Della Rovere regained his position.

But this was just the start of Leo’s troubles. That same year, the pope decided that it was time for a new crusade to ward off the powerful advance of the Ottoman Empire under Selim I. Uniting all of Christendom to fight a common enemy would have been quite a display of Leo’s authority, but it was not to be. The European powers simply distrusted each other too much to play nice together. Leo’s efforts were in vain and, by 1519, he had given up any hopes of carrying out his plan.

And that was still not the worst of it because also in 1517, Pope Leo X may or may not have been the target of an assassination attempt orchestrated by his own cardinals. Remember Leo’s painful anal fistula we mentioned earlier? Well, apparently, some of the cardinals thought that they could do away with him by poisoning his bandages. However, the Petrucci Conspiracy, as it was known, was discovered and foiled…that is, if it ever truly existed.

Five cardinals were named and arrested – the aforementioned Alfonso Petrucci, supposedly the mastermind behind the attempt, Bendinello Sauli, Raffaelle Riario, Adriano Castellesi, and Francesco Soderini. But the case against them heavily relied on the testimony of Petrucci’s majordomo, Marcantonio Nini, which was obtained under extreme torture and not exactly reliable.

But why would Leo want to manufacture a plot against him? Well, let’s look at what happened next. Cardinal Riario was fined the giant sum of 150,000 ducats, while the others paid lesser, but still hefty fines. And they all lost their Church appointments, of course. Meanwhile, Cardinal Petrucci was actually sentenced to death and executed. According to Venetian historian Marin Sanuto, Leo made around half a million ducats from the incident, plus he got rid of five cardinals he didn’t like.

Afterward, on July 1, the pope appointed a staggering 31 new cardinals, more than doubling the size of the college overnight. And many of them were either native Florentines, Medici relatives, or other allies. So with one move, Leo made some serious bank and surrounded himself with loyalists. We’re not saying that the assassination attempt was faked, but we understand why so many others think it was.

Exsurge Domine

And yet, only now do we arrive at Leo’s biggest headache – a pesky German Augustinian friar by the name of Martin Luther. Remember all those indulgences that Leo sold to fill his coffers? As we said, not everyone was on board with the idea and Luther was one of them. He wrote a list of criticisms and propositions known as the Ninety-five Theses and, on October 31, 1517, nailed them to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg, unaware that he was about to trigger a religious revolution known as the Revolution. And just for the sake of clarity, we should mention that the Reformation movement already existed in some places before Luther, but it was his act of defiance that kicked it into high gear.

Pope Leo really didn’t comprehend the magnitude of Luther’s actions until it was too late to stop them. At first, Leo thought that Martin Luther was just another angry nobody who was best left ignored until he faded into obscurity once more. At that time, Leo was more interested in getting his crusade off the ground. But that was not to be, because the theologian’s ideas started to gain traction in Germany.

It wasn’t until January 1518 that the pope appointed three people to study Luther’s writings and decide whether or not they were wrong. Unsurprisingly, they concluded that Martin Luther was guilty of heresy and the German friar was ordered to go to Rome. Wisely, Luther chose to disobey this order. He knew that, if he went, he would likely be excommunicated and probably even sentenced to death for heresy. Fortunately for him, Luther had one powerful protector – Frederick III, the Prince-elector of Saxony. He refused to turn the friar over to the Church despite directives from Pope Leo and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

When that didn’t work, Leo tried fighting fire with fire and challenged Luther in writing with a public decree known as a papal bull. Published on June 15, 1520, it was called Exsurge Domine and was, basically, a diss track against the friar’s radical ideas, which began with the words:

Arise, O Lord, and judge your own cause. Remember your reproaches to those who are filled with foolishness all through the day.

Leo dropped another hot joint in January 1521 titled Decet Romanum Pontificem, this time officially excommunicating Martin Luther from the church. In response, Luther burned the papal bull in public and, at least, in Germany, most of the people were on his side. The Protestant Reformation was now in full swing. Could Leo still do anything to stop it?

We’ll never know. In November of that year, Leo was suddenly stricken with malaria, and, a few days later, on December 1, 1521, he died at the age of 45 and was buried in Rome in the Basilica Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Pope Leo X created a complicated legacy for himself, with some grand ambitions and good deeds tainted by his excessive spending. He left the Catholic Church in a much worse state than he found it. It was nearly bankrupt, forcing the popes who followed Leo to enact desperate austerity measures to cope with all the crippling bills and debts. But more importantly, he left it fractured, as a giant section of his former worshippers decided to abandon the Catholic Church and become Protestants, thus dealing a serious blow to the power, influence, and authority of the papacy from that moment on.