He’s a man known to history literally as ‘the Terrible’. Ivan IV was the first tsar of Russia, the man who built the iconic St Basil’s Cathedral, and the ruler who defended Moscow from Tartar invasion. In Russian history, he’s a towering figure, behind perhaps only Peter the Great and Lenin in how he shaped the nation. Yet how much do any of us really know about him, beyond his mistranslated nickname? Could he really be so bad as the crazed, wild-eyed caricature of popular history?

Well, no. As it turns out, Ivan the Terrible was, if anything, even more terrifying.

Elevated to ruler of Russia when he was just a boy, Ivan showed sociopathic tendencies from the get-go. As a child, he was renowned for torturing small animals. As an adult, he had his opponents torn apart by wild dogs. A bloodthirsty king who killed his own son and created a feared secret police, this is the story of Russia’s sixteenth century Stalin.

“An evil act will spawn an evil son”

On August 25, 1530, Vasili III gazed out the window of his palace as a terrific storm battered Moscow. It was twenty years since the Grand Prince had come to the throne, twenty long years in which he’d tried fruitlessly for an heir. Now, nearing the end of his life, his desperation had got the better of him. He’d divorced his first wife and remarried, scandalizing Moscow.

One religious man had even prophesized that this evil act would produce an evil heir, one who would terrorize the country. We can only wonder if Vasili III was reminded of that prophecy as he looked out the window at the storm wracking Moscow the night his son was born. The Russia Ivan the Terrible was born into was very different from the one we know today.

For one thing, it wasn’t really called Russia, but Muscovy, or The Grand Duchy of Moscow if you want to be old fashioned. For another, it was tiny. Comparative to modern Russia, it was nothing; a landlocked strip hemmed in on all sides by rival states.

But it was something else, too. The Muscovy of 1530 was weak.

The superpowers of the day were Poland-Lithuania – which hadn’t technically yet become a fully joint state, but was so close that we’re just gonna say Poland-Lithuania to keep things easy – and the Khanate of Crimea. Alongside them were a hodgepodge of weaker Islamic Khanates leftover from Ghengis Khan’s Golden Horde, Khanates like Kazan, and Siberia.

Don’t worry about remembering all those names, we’ll remind you of them when the time comes. Just know that, at the moment of Ivan’s birth, Muscovy was a tiny outpost of Orthodox Christianity surrounded by a sea of Islam and Catholicism. Not that this concerned young Ivan much. He was a baby, too busy playing to care about affairs of state. That was what dad was there for.

Yeah, about that.

In 1533, Vasili III contracted an infection which swiftly turned him from ‘strong king’ into ‘dying king’. Sensing the end was near, the Grand Prince summoned the boyars, a class of warrior nobles who held much of Muscovy’s power. Vasili made them swear loyalty to his son Ivan, before setting up a regency with his second wife Elena ruling in Ivan’s name. That done, he promptly died.

Shortly after, on December 4, 1533, little Ivan was proclaimed Grand Prince of Muscovy. While this sounds like every spoiled brat’s dream, the reality was less glamorous. From that point on, his mother Elena insisted he be surrounded at all times by armed guards in case the boyars tried to kill him and assume the throne. But Elena needn’t have worried that the boyars might kill little Ivan. Why murder a child when it’s so much easier to simply replace his regent?

On April 4, 1538, Elena died, almost certainly assassinated by the boyars. Her death set off an explosive power struggle in the Muscovite court. For Ivan, this meant spending his late childhood trapped in a whirlwind of cruelty. The boyars knew no limits. Like warlords, they would do anything to keep themselves in power. In one instance, Ivan witnessed a mentor being skinned alive for crossing a powerful family.

It was also a time of neglect. Ivan would later recall that – despite living in a palace – he wore only rags, and often had to beg for food. The only time the boyars cared about the young Grand Prince was when some foreign dignitary visited. Then Ivan would be dressed up and paraded about before being dumped back in his gilded prison.

With all this cruelty around him, it’s perhaps no surprise that Ivan began taking out his anger on animals. By age 12, he was torturing cats, much as he’d witnessed the boyars torturing their rivals. But if the boyars thought they could cow this weak and useless boy, they were about to learn a terrible lesson.

Ivan may have barely been a teenager. But already he was plotting his revenge.

Building The Third Rome

On December 29, 1543, a group of guards marched into the quarters of one of the cruelest boyars in Muscovy. Saying they were following the Grand Prince’s orders, the guards arrested the man, dragged him away…and fed him alive to a pack of wild dogs.

It was the Middle Ages equivalent of walking into the prison yard and punching the biggest, meanest skinhead smack in the mouth. Aged only 13, Ivan had just ordered his first gruesome murder. From that point on, the boyars would show him respect. Not that Ivan did the same for others around him.

By 14, the newly-confidant Grand Prince was wandering the streets of Moscow with his teenage friends, beating and robbing any citizen unlucky enough to cross his path. Yet it would be unfair to say that Ivan was merely a thug. At the same time he was getting a taste for brutality, the boy was getting a taste for something else, too. Ivan was discovering religion.

Around the same time as his first murder, Ivan had fallen under the sway of a Metropolitan known as Macarius, who had impressed upon Ivan the need for Muscovy to become a bastion of Orthodox Christianity. And Macarius knew just how to do that.

In 1547, Ivan’s regency finally came to an end. On January 16 , he was crowned Tsar Ivan IV of all Russians in a lavish ceremony overseen by Macarius.

This was a super big deal. Ivan was the first person to be crowned tsar. By using that title, and by using Byzantine trappings in the coronation, Ivan and Macarius were positioning Muscovy as the successor state to the lost Byzantine Empire; the defender of the Christian faith. They even began calling Moscow the Third Rome. Three weeks after this audacious ceremony, Ivan held another one.

On February 3, 1547, Tsar Ivan IV married a young girl called Anastasia. You’ve probably never head of her, but you have heard of her family. Anastasia was from the Romanovs. In the not-too distant future, her family was going to transform Russia. But only after Ivan had had his turn. No sooner was the Terrible on the throne than he was firing off edicts, reshaping Muscovy with far-reaching reforms.

Surprisingly, not all these reforms were terrible.

To go through all of them would take forever, but you can sum them up as being largely about accountability. In the mid-sixteenth century, the aristocrats could generally get away with just beating you to death in the street because they felt like it. Ivan’s new laws said “hey, actually, you can’t just kill commoners for no reason.” It may not sound like much but, coupled with the introduction of localized government and Muscovy’s first professional army, it was a minor revolution.

Still, let’s not kid ourselves that Ivan felt bound by his laws. He’d designed them specifically to weaken the power of the boyars. When a bunch of commoners came to him to complain about a corrupt official, Ivan had all 70 of them stripped naked in the snow before setting their beards on fire. Still, by the time his fifth anniversary on the throne rolled around, Ivan was in a pretty good place domestically. He’d consolidated power, won the public’s approval, and weakened the hated boyars.

Now he just needed his shiny new state to find a way of living up to that whole Third Rome thing.

And what better way to do that than to launch a crusade?

The Fires of Victory

OK, time to check back in on all those neighbors we mentioned earlier. Remember? The ones leftover from Genghis Khan’s Golden Horde? Well, the last few years had seen the Khanate in Crimea growing bolder. Tartar armies were starting to harry the fringes of Muscovy.

But Crimea was far too strong for Ivan to deal with now. No, he and Macarius had their sights set on somewhere a little closer to home: Kazan. A minor Khanate sat on the Volga River, Kazan was technically a threat to Muscovy, but was actually a political basketcase.

That’s not to say they were helpless. Over the years, many Muscovite armies had tried to conquer Kazan, and just as many had failed. Now he was secure in his position, Ivan was determined to show everyone how it was done.

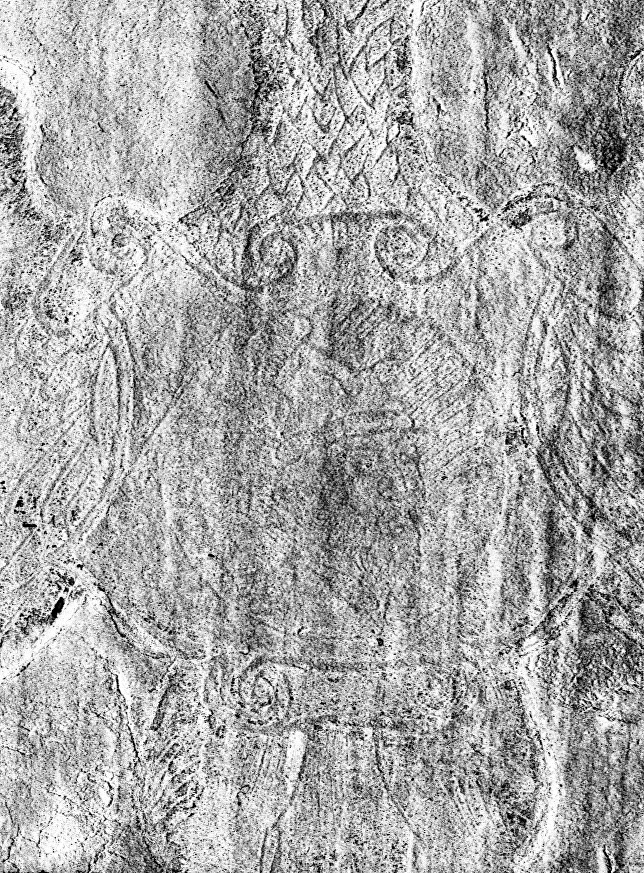

On June 16, 1552, Ivan IV rode out at the head of a vast army.

Since this was his first major war, it was imperative that everything went well. To that end, Ivan put aside hours per day for praying, begging the Christian god to help him crush the Muslim infidels. It seemed God was listening.

On September 2, Ivan’s armies laid siege to Kazan. They cut off supplies, destroyed access to drinking water, and built huge earthen works to defend from cavalry attack.

By early October, it was over.

Kazan fell on October 13, just two days after Ivan’s son Dimitri was born. Although the Khanate tried to return, it was effectively dead. Ivan had done it. Not just done it, but done it with astounding ease. Had he died now, it’s likely that Ivan would’ve gone down in history as a great ‘What if?’, a ruler history buffs singled out as someone with the potential to be a legend.

This is worth thinking about, because, in 1553, Ivan really did nearly die. That year, Ivan fell deathly ill. Thinking it was the end, he did as his father, Vasili III, had done, and summoned the boyars to swear an oath to his son Dimitri.

This time, the boyars refused.

They prefered Ivan’s cousin. If Ivan really was dying, he was just gonna have to deal with this being the end of his royal line. However, Ivan didn’t die. He recovered, but came back slightly changed.

Always a paranoid man, Ivan felt like his illness had confirmed his darkest fears. The boyars really were out to get him. At that moment, Ivan vowed to get them first.

The Jaws of Defeat

Come winter, 1557, Ivan was looking for an excuse to expand Russia’s boarders. The year before, his armies had annexed the other Khanate on the Volga, Astrakhan, giving Muscovy clear access to the Caspian Sea. But all the victory had done had convinced Ivan that his new Russian state needed access to an actual sea, one that connected to real oceans.

One like the Baltic Sea. In those days, Muscovy was bordered by something known as Livonia, a state roughly analogous to modern day Latvia and Estonia.

While Kazan had been a remnant of the Golden Horde, Livonia was a remnant of the land the Teutonic Knights had conquered. But with the Knights now gone and Protestantism on the rise, Livonia’s Catholic rulers were starting to look weak. Then, in December, 1557, King Sigismund of Poland-Lithuania inserted himself into Livonia’s affairs, forcing the nation to sign a treaty with him.

For Ivan, this flagrant provocation was the excuse he’d been looking for.

The moment the atrocious winter weather cleared up, Ivan was leading a full-on invasion force into Livonia, determined to carve a path to the Baltic coast. To say the war started well is to miss just how easy a victory this was. The new Muscovy armies steamrollered the Livonians. By 1560, the Livonian Order was in ruins, and its Grand Master had been dragged off to Moscow and executed.

It should’ve been another easy win for Ivan. Unfortunately, it was anything but. In 1561, a new Grand Master was appointed for Livonia. With commendable slyness, he surrendered not to Ivan, but to Sigismund, thereby giving Poland-Lithuania a claim to the territory Russia had occupied. At the same time, the Grand Master ditched his Catholicism and invited the Protestant Swedes to invade and restore order in the north.

And, just like that, Ivan found himself suddenly stuck knee-deep in a war that would last the next twenty years.

It couldn’t have come at a worse time.

In 1561, Ivan was still reeling from the double whammy of his son Dimitri’s death, and the suspected assassination of his wife, Anastasia. Although Ivan still had two heirs – his sons Ivan the younger and the mentally challenged Fyodor – the sudden loss of two family members still left him bitter.

When Metropolitan Macarius too passed away in early 1563, Ivan seems to have lost it. That same year, he beat one of his own soldiers to death – the first murder the tsar committed with his own hands. But it was the events of April 30, 1564, that would really make Ivan into ‘the Terrible’.

That day, Ivan’s best general, Andrey Kurbsky, defected to the Lithuanians. This seems to have floored Ivan. Raging that the boyars were making a fool of him, he announced he would abdicate the throne. You might expect the boyars to jump for joy at this. After all, this was the guy who’d had one of their number thrown to wild dogs.

But this was war. If the tsar left now, the power vacuum it created would potentially cause Russia to implode.

The boyars had no choice. They begged Ivan to stay. In early 1565, Ivan finally agreed, on one condition: that he be allowed to create a new mini-state within Russia itself, a place where he would rule as God, without any checks or balances. Backed into a corner, the boyars agreed.

It was a decision that would set Muscovy on the path to Hell.

The Oprichnina

Shortly after, Ivan divided his nation into two parts: the Zemschina and the Oprichnina. The Zemschina was where things carried on as before, almost unchanged. The Oprichnina was where Ivan’s darkest impulses came out to play.

The Oprichnina covered about a third of Muscovy’s territory, but it wasn’t as simple as drawing a line on a map.

Ivan was allowed to choose what he wanted in his new kingdom, so naturally he selected the richest towns, meaning the borders between Oprichnina and Zemschina were often blurred. In Moscow itself, the border could change street by street, even house by house. You might never know when you were suddenly subject to Ivan’s whims. And this was a problem, because it wasn’t Ivan doing the Oprichnina’s dirty work.

It was the Oprichniki.

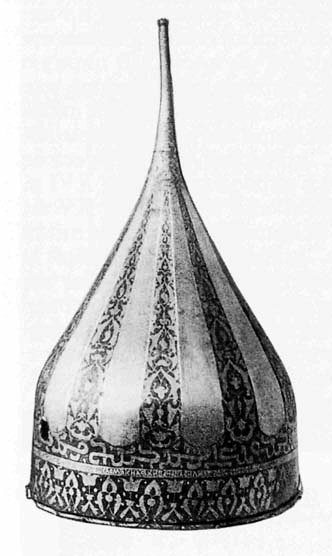

An army of around 6,000 men, the Oprichniki were effectively Russia’s first secret police. Dressed all in black, they rode black horses and drove black carriages designed to instill fear. They were completely above the law, given the right to torture, rob, rape or kill anyone they felt like, and to burn down whatever buildings they wished to. Known as “children of darkness”, they had one mission: to terrify the populace into submission.

You better believe they succeeded.

To relate every awful thing the Oprichniki did would result in this video being 10,000 hours long and giving all of us PTSD. So let’s just stick to examples, like the palace they used for their headquarters, where it’s said twenty people were tortured to death every single day. Or like their sadistic commander, Malyuta Skuratov, who liked to round up married women from across Moscow and have them all raped for his entertainment.

With Ivan’s blessing the Oprichniki targeted boyar families, murdering or driving them into exile, seizing the properties they left behind. By the end of the 1560s, they had turned so many wealthy families into refugees that the Oprichniki had managed to set themselves up as a new aristocracy. But where was Ivan in all this?

Leading from the front. In early 1570, for example, Ivan became convinced that the city of Novgorod was about to join the Lithuanians. There was no evidence for this. In fact, Ivan had to make his rapist-in-chief Malyuta Skuratov forge documents to “prove” Novgorod was on the verge of rebelling.

Nevertheless, on January 2, Ivan rode out at the head of a vast Oprichniki army. For the next month, the Oprichniki were allowed free run of Novgorod, killing, burning, maiming like some demented, sixteenth century version of The Purge.

Citizens were hanged by the hundreds. Others were tied up and dumped into the ice-covered river. Those that managed to get back to the surface had their heads caved in with axes. By the time the Oprichniki left Novgorod on February 12, there was no Novgorod left.

In one short month, the Oprichniki had killed anywhere between 6,000 and 12,000 people. Back in Moscow, Ivan followed this brutal, pointless act by accusing boyars of conspiring with Novgorod and having them executed. By now, there was a feeling like nobody in Muscovy was safe. That this horror would never end.

However, help was about to come from an unlikely source.

War is Over

The Oprichnina’s end came suddenly, in spring, 1571. There were rumors that a Crimean Tartar force was marching toward Moscow, but Ivan barely bothered to prepare. After all, his Oprichniki spies had told him the force was a few thousand strong at best. In fact, the advancing army contained over 120,000 soldiers. By the time Ivan got the news, any chance to fortify the city was gone.

So Ivan simply grabbed as much treasure as he could and fled, leaving Moscow to its fate. And what an awful fate it was.

The Tartars ransacked the city. Muscovites were dragged away into slavery. Children were slaughtered in their homes. Every single building but the Kremlin was burned to the ground. By the time the Tartar force retreated, on May 26, over 160,000 Muscovites were dead or in chains. So many bodies had been dumped in the river that it had actually changed course.

The next year, Ivan abolished the Oprichnina. Perhaps to cover his own failings, he also unleashed a new terror against the Oprichniki for failing to protect Moscow, paying back blood with blood. But it was little use. Russia was by now a war-shattered ruin, with an exhausted populace and an economy on the brink of collapse.

Perhaps the only silver lining was that the Crimean Tartar army finally overextended itself shortly after and was crushed by regular Russian forces. Still, this offered only limited respite. If Ivan were to save his nation, there was only one thing he could do.

Ivan would have to end the Livonian War. But he didn’t. Although it was by now clear that his boneheaded invasion of the Baltics had caused these endless crises, Ivan still couldn’t give up his old ways.

In the early 1570s, he even tried instituting a new reign of terror, having his opponents at home roasted alive.

But his real enemy was the senseless paranoia in his own mind. While Ivan was busy killing boyars, Poland-Lithuania’s new king was invading Russia, and the Swedes were reconquering Russia’s gains in Livonia. Yet Ivan refused to listen to reason. No matter what happened, he failed to see that he himself was at fault.

However, while Ivan the Terrible was having a truly terrible time, his son Ivan was doing rather better. A capable general, Ivan the younger had fought the Polish-Lithuanian army in battle and acquitted himself well. So well, in fact, that the boyars wrote to Tsar Ivan saying “hey, doofus. Why not have this guy be leader, huh?”

They meant leader of the army. But Ivan the Terrible thought they meant to make his son tsar. It was a suggestion he didn’t take kindly.

In November, 1581, shortly after receiving the boyars’ petition, Ivan stumbled across his son’s pregnant wife.

In a rage, he beat her so savagely that she miscarried. When his son came to complain, the old monster grabbed his staff and hit the boy around the head with it. He kept right on hitting him until his skull had broken and the floor was slick with blood.

Ivan the younger died of his injuries on November 19, 1581. It’s said that Tsar Ivan reacted to his passing by wailing “my God, what have I done?”0

But it was even worse than the puffed-up sadist realized. With Ivan the younger as dead as Dimitri and Anastasia, the last heir to the throne was Ivan’s simple-minded son Fyodor.

In just a few short years, Fyodor’s ascension to the throne was going to both plunge Russia into chaos, and end Ivan the Terrible’s family line for good.

The Price of Peace

If nothing else, the death of Ivan the younger seems to have finally focused Ivan’s crazed mind. In 1581, the Tsar of all Russians formally asked the Pope to negotiate an end to his war with Poland-Lithuania. The eventual peace process saw Russia surrender all its gains in Livonia. A separate peace with Sweden saw Russia abandon its claims to coastal towns on the gulf of Finland.

After twenty four years of war… after the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people… Russia was right back where it had been in 1558.

All that horror. All that suffering. The Oprichnina, all of it.

All had been for nothing.

The only silver lining had been the destruction of the Khanates in the early days of Ivan’s reign, and the implosion of the Crimean army after it sacked Moscow. And the second of those had been in spite of Ivan, rather than because of him. Interestingly enough, Ivan scored one other great victory in the last days of his reign that had absolutely nothing to do with him.

In 1583, the Stroganoff family – yep, just like the dish – rode a private army into Siberia almost on a whim and defeated the Khanate there. This simple victory would open up Russian expansion into Siberia for centuries to come, providing a wealth of riches that would help bring the nation back to its former glory.

So, um, well done Mr. Stroganoff.

By 1584, Ivan was so ill that even leaving bed was too much for him. His only solace was playing chess, something he was doing on March 18 when a stroke allegedly carried him off. We say “allegedly” because it’s long been rumored that the tyrant tsar was simply strangled by fed-up boyars.

In the aftermath of Ivan’s death, Fyodor took the throne, but was so useless that his rule led to something called the Time of Troubles, a fifteen year period of civil wars and uprisings that made the Oprichnina look like Disneyland constructed from unicorns. In fact, the chaos Ivan the Terrible left in his wake only cleared when Anastasia’s old family, the Romanovs, finally seized power in 1613.

At the end of all that, then, what can we say about the man known to history as “the Terrible”?

Well, he certainly lived up to his nickname! Seriously, next time someone bangs on about how “Terrible” is a mistranslation of Grozny, just remember that, mistranslation or not, “Terrible” is certainly appropriate. But there are darker lessons we can take from Ivan’s story.

The idea of an unaccountable leader who ruled through fear, and of a secret police run by sadists with no checks on their power would return 500 years later, under perhaps the only Russian leader more terrible than Ivan.

It’s said that Josef Stalin admired Ivan the Terrible. Maybe he felt a kindred spirit, calling to him down through the years, encouraging him to go even further, to commit even worse crimes than had happened during the Oprichnina. It’s often said that history repeats itself. Well, even the briefest look at Russian history will show you that Ivan’s tale repeated itself again and again, like a record needle stuck in a groove.

Ivan may have been the first crazed autocrat to terrorize Russia.

But, he wouldn’t be the last.

Sources

Good podcast series, with several episodes on Ivan (episodes 14-22): https://podcasts.google.com/?feed=aHR0cDovL3J1c3NpYW5ydWxlcnMucG9kaG9zdGVyLmNvbS9yc3MvMjc0Mi8%3D&hl=en-CZ

Podcast on Ivan’s early years and the Khanates: https://player.fm/series/a-history-of-europe-key-battles/ep-442-ivan-the-terrible-early-years

Britannica’s biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ivan-the-Terrible

ThoughtCo biography: https://www.thoughtco.com/ivan-the-terrible-4768005

What the hell is Livonia? http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_livonian_1558-83.html

What the hell is Poland-Lithuania? https://www.britannica.com/event/Union-of-Lublin

The Oprichnina explained: https://www.thoughtco.com/the-oprichnina-of-ivan-the-terrible-3860937

More detail on the Oprichnina: https://books.google.cz/books?id=63i0BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA406&lpg=PA406&dq=Oprichniki+Palace&source=bl&ots=gn4yv-lceL&sig=ACfU3U00XWhF2yjwMSNGh7-U4Ijvy7gSwQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwip2sbSzMPkAhXhMewKHVpkAI4Q6AEwEHoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=Oprichniki%20Palace&f=false

Time of Troubles: https://www.britannica.com/event/Time-of-Troubles