“During a happy period of more than fourscore years, the public administration was conducted by the virtue and abilities of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the two Antonines.”

Those are the words of 18th century historian Edward Gibbon, exemplifying the concept of the Five Good Emperors – five Roman rulers who successively governed the empire “by absolute power, under the guidance of wisdom and virtue.”

Hadrian was there right in the middle. He left behind the legacy of a builder. As he traveled throughout the regions of his empire, he founded new cities, while all the existing settlements he encountered benefitted from some kind of improvement, whether it was a new theater, a bath house, or even just a donation for the future. He enacted sensible policies and strengthened the position of his armies even though he had no grand military ambitions.

That being said, Hadrian was definitely no saint. People quickly fell out of his favor and, as you will see, those who opposed or slighted him met their violent ends. He also curtailed the powers of the Senate and leaned more towards an autocratic rule. For this reason, scholars see Hadrian as a mercurial character. One whose outwardly displays of geniality and restraint could have simply been a façade hiding a devious and hedonistic mind. Or maybe he was just an emperor who wanted to help his people as best he could. It really is hard to say and, for millennia, Hadrian has been a puzzle that historians have struggled to solve.

Early Years

Hadrian was born Publius Aelius Hadrianus on January 24, 76 AD, although his place of birth is still somewhat uncertain. Although most sources indicate that he was born in Italica, a settlement in the province of Hispania Baetica, others say that his family may have actually been in Rome at the time of his birth, which would not be so far-fetched given that his father, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, was a Roman Senator.

His mother was named Paulina, retroactively referred to as Paulina the Elder to help distinguish her from Hadrian’s sister and his niece who both shared the same name. Another relative we should highlight and, perhaps the most important one of all, was an uncle of Hadrian named Marcus Ulpius Trajanus. He is better remembered as the Roman Emperor Trajan, and he will play a major role in Hadrian’s life. His own reign was also quite notable, perhaps the best one of all and, guess what, we’ve already done a Biographics video on the life of Trajan. If you missed it, why not give it a watch right now, and then come back here where we will pick up pretty much where that one left off.

In 86 AD, Hadrian lost both of his parents. It was a terrible blow for a young, 10-year-old boy, but he had a modicum of good fortune as Trajan took him and his sister under his wing as his wards, as did another powerful official named Attianus who was a friend of his father’s.

This was still over a decade before Trajan took the throne, but he still had the money and influence to ensure that Hadrian received a good education and then started climbing through the ranks of Roman bureaucracy.

As was expected of him, Hadrian entered public service, on the path to become a Roman Senator like his father. He started out as a lowly civil servant, and then served several times as a military tribune. Unsurprisingly, when Trajan became the new emperor, the positions held by Hadrian significantly improved, but even so, Trajan was careful not to promote him too fast, and there was even a 10-year period when Hadrian did not rise through the ranks at all. He served, among others, as quaestor, tribune, praetor, consul, and legate. He was also able to indulge his passion for Greek culture when he traveled to Athens, where he was granted citizenship and named as one of the archons, the officials who handled the city’s affairs.

Rise to the Throne

As with any succession worth mentioning, Hadrian’s rise to the throne of Rome was marked by intrigue, violence, and controversy.

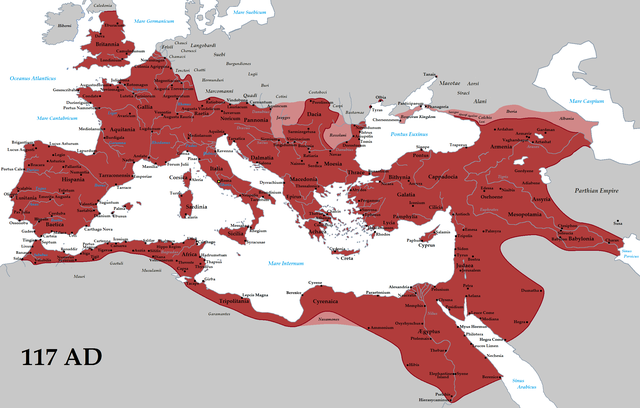

At the time of Trajan’s death, Rome was at war with the Parthian Empire in Western Asia. The conflict was not going in his favor and he also had to contend with several rebellions in other parts of his empire. In 117 AD, Trajan fell ill, so he set sail back to Rome, while Hadrian became the de facto commander leading the Romans against Parthia as the new governor of Syria. Trajan never made it home, though, as he died during the journey on August 8.

Now, of course, came the matter of who will become the new emperor. Trajan and his wife, Pompeia Plotina, had no children of their own. And he never named an heir. Or did he? Because around the time of his death, some letters appeared, seemingly written by Trajan, where he named Hadrian as his adopted son and heir to the throne.

So did Trajan actually write those letters? That is the question that still troubles historians. Many believe that Hadrian’s succession was, in fact, the work of Plotina, and his other guardian, Attianus, who both wanted Hadrian to rule because one – they liked him, and two – it meant that they would maintain their privileged positions by the emperor’s side.

And this is not a belief of only modern scholars. Ancient historians like Cassius Dio, who is one of our main references for Hadrian, said the same thing in his Roman History, written less than a hundred years later. He even had a great source for his opinion – his own father, Apronianus, who served as senator and governor of Cilicia. Cassius Dio claimed that his father established with accuracy, as did other senators, that the succession of Hadrian had been engineered by Plotina, as it was her signature on the letters allegedly written by Trajan, something she had never done before. He also said that Plotina delayed the announcement of her husband’s death so that the people might first hear of Hadrian’s adoption.

Surprisingly, despite the suspicions, Hadrian’s ascension to the throne went smoothly and unopposed. Some have argued this was because, even if Trajan did not name him as his heir, he probably would have been ok with Hadrian becoming the next emperor. After all, Trajan took him on as his ward. He looked after his political career. He arranged for Hadrian to marry one of his grandnieces, Vibia Sabina, and, during times of war, he showed that he trusted Hadrian by placing him in charge of the troops.

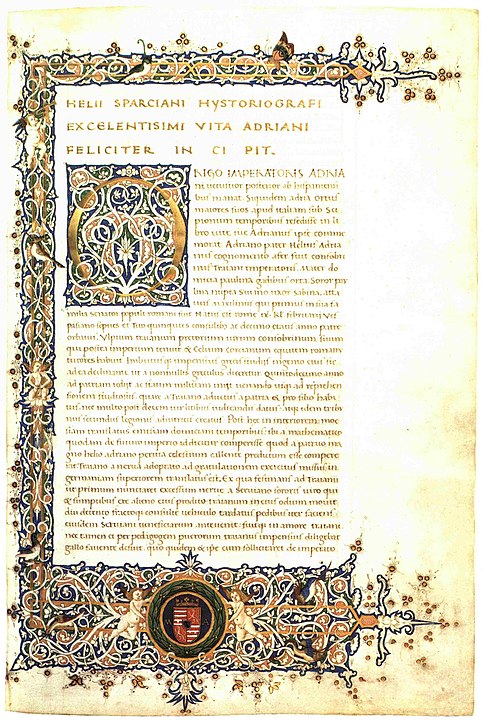

Furthermore, if Trajan did have someone else in mind, he probably would have named him by then. The Historia Augusta mentions a rumor that Trajan intended to name one of Rome’s leading jurists, Neratius Priscus, as his successor, but this is the only source on the matter and is generally considered pretty unreliable.

A Rocky Start

On August 10, 117 AD, Hadrian became the new Roman emperor. He was still in Syria, and he took his time before heading to the capital, putting down some of the rebellions that had erupted during the reign of his predecessor. He did, however, write letters to the Roman Senate. Some were boilerplate stuff – asking the Senate to confirm his sovereignty, choosing an official title for himself, pledging to serve the public interest, making arrangements for Trajan’s funeral and deification, and so on. He also wanted to get on the good side of the Senate so he swore an oath never to put to death any senator. He then immediately proceeded to break this oath or, at the very least, it was broken in his name.

We are not sure on the precise circumstances, but soon after Hadrian’s ascension to the throne, four of Rome’s most powerful senators were accused and convicted of several charges, including conspiracy against him. They were Palma, Nigrinus, Celsus, and Quietus. None were actually in Rome at the time so they were convicted in absentia without a public trial, sentenced to death, then tracked down and killed. This immediately turned the Senate against Hadrian, with an enmity that lasted for his entire reign. Even when he died, the Senate wanted to deny him divine honors and pretty much had to be forced to do it by his successor.

For his part, Hadrian always denied any involvement in the deaths of the four senators. His guardian, Attianus, was almost certainly responsible, but it remains a matter of pure speculation of whether Hadrian knew and approved of his actions or not. Given the power and influence of the four slain officials, it would not be out of the question for Attianus to fear that they might oppose Hadrian’s succession, but this is just conjecture. The Historia Augusta which, again, contains a lot of statements that are demonstrably false, claimed that the four officials conspired in a murder plot against the new emperor.

Those senators were not the only prominent men slain by Hadrian, if Cassius Dio was anything to go by. He also accused the emperor of banishing and then putting to death Apollodorus of Damascus, the famed architect who was responsible for most of the landmarks built under Trajan, including his triumphal column and the bridge across the Danube. All of this because Apollodorus had insulted Hadrian once back when Trajan was still emperor, by mocking his plans for a new building.

One may start to wonder why exactly Hadrian was considered a “good emperor” in the first place, given his propensity to eliminate those who slighted him, but it was also Cassius Dio who came in his defense, arguing that all of Hadrian’s faults were atoned for by “his careful oversight, his prudence, his munificence and his skill.” The historian posits that, throughout his lengthy 21-year reign, Hadrian did not seek out war, but terminated the conflicts already in progress. A strict and disciplined man, he made sure his legions were the same and that they would never be guilty of insolence or insubordination. He never deprived anyone of their wealth without cause but, quite the contrary, often bestowed generous sums upon citizens or entire communities, and that he, more than any other emperor before him, assisted almost all of his allies and subject cities, “giving to some a water supply, to others harbours, food, public works, money and various honours.”

Inside the Empire

We’ve given an outline of Hadrian’s reign, with the good and the bad, but now let’s get into more details. He arrived in Rome in 118 AD for his coronation. He did the standard stuff to get the public on his side: he organized games, made donations, gave bonuses to soldiers, canceled debts, etc. He also quote-unquote suggested to Attianus to give up his position as Praetorian Prefect and go into retirement in 119. Whether this was done as a gesture of goodwill towards the Senate or because Hadrian genuinely had no involvement in the deaths of the four senators, we don’t know. Attianus was replaced with two other men – Septicius Clarus and Marcius Turbo.

One of Hadrian’s first major acts as emperor was a ballsy one – he reversed Trajan’s policies in Western Asia and willingly surrendered the territories his predecessor had gained in Mesopotamia. It wasn’t a glorious move, but it was practical. Hadrian understood that Rome might have been powerful enough to conquer the region, but did not have the soldiers and resources to keep it and maintain peace. If he insisted on continuing Trajan’s expansionist approach, he would have to deal with one rebellion after another. Instead, what Hadrian liked was to use natural borders to consolidate the empire he already had, so he gave up Rome’s claim to everything east of the Euphrates River. This remained the Roman approach for the following four decades, until Rome went to war against Parthia once again in 161 AD.

Inside the empire, Hadrian enacted multiple reforms to benefit the people of Rome, some which went against long-established Roman traditions. For example, when someone was charged with a major crime, it was common to confiscate their estate. According to the new law, if that person had children, they were allowed to inherit a portion of their wealth.

Hadrian also reclassified middle-class officials, soldiers, veterans, and their families as honestiores. This was one of two categories of Roman citizens, representing the high caste, as opposed to humiliores, which was the low caste consisting of freedmen and slaves. This distinction was important because honestiores benefitted from multiple legal privileges, particularly when it came to criminal law. They almost always received more lenient sentences while the cruelest punishments, such as being crucified or thrown to the beasts in the arena, were reserved only for humiliores. So while the wealthy enjoy preferential treatment in most societies, it was actually part of Roman law that they were granted these privileges. And although Hadrian did not get rid of such concessions, he at least made them available to more groups of people.

Some of the emperor’s policies even benefitted slaves as he limited the punishments that could be inflicted upon them. Hadrian made it illegal for citizens to kill their slaves just because they felt like it. They could only do it if the slaves were found guilty of a capital offense. And the slaves could not be sold to gladiator schools or brothels unless, again, it was as punishment for a crime they committed. Granted, it’s still not much in hindsight, but it’s more than most other emperors ever did to benefit the lowest class of people in Rome.

Hadrian’s Grand Tour

Hadrian’s reign was characterized by one thing more so than anything else – travel. He traveled throughout his empire more than all the previous emperors, going from region to region, preferring to see things for himself rather than relying on reports from others. Other rulers usually just stayed in Rome and only left when it was time for war. Hadrian, on the other hand, spent over half of his reign outside Rome, founding new cities and improving the ones that already existed. He also gave plenty of attention to his military fortifications in order to better protect his empire from external and internal threats. He ordered the construction of new forts and garrisons, had others moved to more favorable positions and some, he had demolished.

Hadrian embarked on this tour of his empire in 122 AD. His first stop was Britannia, aka the part of Great Britain which was a Roman province. There, he ordered the construction of, arguably, the most famous structure that bears his name – Hadrian’s Wall, a 73-mile defensive fortification that traveled from the east to the west of the province. When it was finished, it had 80 small forts called milecastles, plus 17 larger forts which were used to garrison auxiliary soldiers from all over the empire. Initially, it was abandoned right after Hadrian’s death because his successor wanted to build his own wall further up north into Scotland. However, that second wall was subsequently also abandoned as the following emperors preferred to rely on Hadrian’s Wall which, from that point on, remained in use for 300 years and large parts of the wall still stand today.

After Britannia, Hadrian returned to mainland Europe and traveled through parts of what is today France and Spain, before sailing for North Africa. While the trips themselves were not problematic, the emperor had to deal with a few issues in Rome. Pompeia Plotina, the widow of Trajan and his former guardian, had died, so Hadrian made arrangements to have her deified and built a temple in her honor in Nemausus, today the city of Nîmes in France. Furthermore, the emperor dismissed two of his close confidants from his inner circle for, allegedly, behaving with “great familiarity” towards his wife Sabina. They were Septicius Clarus, one of the two Praetorian Prefects, and the historian Suetonius, who held the position of ab epistulis, or the “minister of letters” who handled the imperial correspondence. What happened to them after this point remains uncertain.

Upon arriving in Africa, Hadrian had to put down a rebellion by the Moors. Afterwards, he cut his trip short when word reached him that Parthia might have been preparing for war again. He hurried to Asia where he made sure that Roman defences were up to snuff and, after discussions with the Parthian King Osroes I, ensured that there would be peace between their empires, at least for the time being. While he was there, Hadrian visited the Roman provinces in Asia Minor and that is where he met Antinous, a Bithynian youth that the emperor fell in love with. He quickly became a favorite of Hadrian who first sent him to Rome to complete his education and then afterwards made him a part of his retinue as the lovers continued their journey throughout the empire.

The last stop before Hadrian finally returned to Rome in 126 AD was Greece, one of, if not his favorite place in the world. He spent almost a year there, mostly in Athens, taking part in their games and rituals, funding public works and festivals, and even getting initiated in the Eleusinian Mysteries, one of the most secretive religious rites of ancient Greece. Today, there are still plenty of remnants left to remind the world of Hadrian’s voyage. There is an Arch of Hadrian in Athens, there is an even more impressive one in Jordan, there’s Hadrian’s Gate in Turkey; not to mention that he dedicated resources to finish or rebuild older structures, like the Roman Pantheon and the Temple of Zeus in Athens.

After a couple of years spent in Rome, Hadrian got restless again and set out on another tour in 128 AD, this time starting with Greece. He then set off for Egypt since he had to cut his time in Africa short during his first voyage. Here, tragedy befell the emperor. In September or October 130, his lover Antinous died, apparently by falling and drowning in the River Nile. There were some whispers that he may have been murdered as part of a conspiracy against Hadrian, while Cassius Dio claimed the young man sacrificed himself willingly so that the gods may cure Hadrian of an unknown illness. Whatever happened, the emperor was distraught over the death of the young man and, to honor him, he founded a new city on the river bank where he perished and named it Antinoopolis.

Even more, Hadrian had his lover deified and declared a god. A cult of worship developed around Antinous and, although the emperor obviously encouraged and supported its spread throughout the empire, even he probably did not expect it to become as big as it did. The cult lasted for over 200 years after Trajan had died, with over two dozen temples dedicated to the worship of Antinous being built throughout the empire and thousands of statues being made bearing his likeness.

Rebellion in Judea

Hadrian got to enjoy a lengthy rule mostly devoid of serious military conflicts, but there is one giant exception. In 132 AD, the Roman Empire fought a rebellion in Judea called the Bar Kokhba Revolt, which dominated the last part of Hadrian’s reign.

Tensions had been high in that region for decades and this conflict is considered part of the larger Jewish-Roman Wars which went on for 70 years. As to what factors triggered this particular uprising, the most discernible motive seemed to be the construction of a new Roman city called Aelia Capitolina over the ruins of Jerusalem, which included a temple dedicated to Jupiter built on Temple Mount, which was a holy site for the Jewish populace.

The rebellion was led by one Simon Bar Kokhba, hence the name of the revolt. He wasn’t just the military leader, but he came to regard himself as a Messianic figure who may have had up to 400,000 soldiers following him during the uprising.

At first, the Romans did not expect the rebellion to grow as fast or be as ferocious as it turned out to be. They were completely overwhelmed and, soon enough, the rebels controlled the region. This area in Judea basically became independent for over two years, with the rebels even striking their own currency

Eventually, though, Hadrian called in one of his most accomplished generals, Sextus Julius Severus, as well as reinforcements from other provinces. The Romans started winning battles and forcing the Jewish rebels to withdraw until they had to fall back inside the ancient fortified town of Betar. What followed was a long siege, but Betar also fell eventually and Simon Bar Kokhba died during that battle in 135 AD.

Although his numbers can only serve as a rough estimate, Cassius Dio claimed that over 1,000 villages and outposts were razed during the rebellion, and roughly 580,000 men were killed in the fights, plus countless more perished of famine and disease, or were sold as slaves.

Final Years & Succession

Hadrian returned to Rome around 134 AD and never really strayed far outside its limits for the remainder of his life. If the Historia Augusta is to be believed, he became more paranoid and violent in his later years, putting to death influential men who he thought might be conspiring against him. According to rumors, the emperor even poisoned his own wife, Sabina, who died in 136 AD.

As Hadrian was getting older and began suffering from various ailments, he had to consider his successor. Like Trajan before him, he had no children of his own, so he would have to adopt someone and designate him as his heir.

The first name that was thrown around was Servianus, one of Hadrian’s longest-serving advisors. He had been treated for years as the unofficial successor, but he was too elderly to become emperor. He was 90 years old when he died in 136 AD so, instead, the emperor thought about naming Servianus’s grandson, Fuscus, as his heir. However, Hadrian soon changed his mind, and went with a different man named Lucius Commodus. Not only that, but he had Servianus and Fuscus put to death, allegedly because they “were displeased at his action.” What exactly this is supposed to mean, we’re not sure. Did they simply complain about the emperor or is this a nice way of saying they tried to stage a coup? Either way, before being executed, Servianus allegedly got on his knees and said : “as for Hadrian, this is my only prayer, that he may long for death but be unable to die.” This became incredibly prophetic, as Hadrian did, indeed, die a slow, painful death, and was prevented from committing suicide several times.

As far as his heir was concerned, he adopted the name Lucius Aelius, but he turned out to be a poor choice as successor. He was actually the son-in-law of Nigrinus, one of the four senators killed at the start of Hadrian’s reign. Because of this, some see this choice from Hadrian as atonement for their deaths, suggesting that he may have been involved, after all. Regardless, Lucius Aelius died in 138 AD, a few months before Hadrian, so the emperor had to select another heir. This time, he went with Antoninus Pius, who did indeed succeed him as Roman Emperor when Hadrian finally perished on July 10, 138 AD, aged 62.