The year was 1968 and, in the evening, America sat down to watch The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour on CBS, a variety show that featured comedy skits and musical guests. But this wasn’t your average variety show. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour broke away from the traditional formula and quickly evolved into a program that wasn’t afraid to push the boundaries. Political satire, the Vietnam War, religion – these were topics that you simply wouldn’t see on other programs that played it safe, but you could see them here.

Because of this, The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour was a big hit with the younger generations and became known as a place that would feature a lot of new acts representative of the counterculture era of the 1960s.

Among these acts was an up-and-coming comic named George Carlin. But he wasn’t the same Carlin that most of us would be familiar with. Not yet, at least. He was dressed in a crisp blue suit, clean-shaven, with his short hair neatly parted to one side. Suffice to say that he had not found his “look” yet.

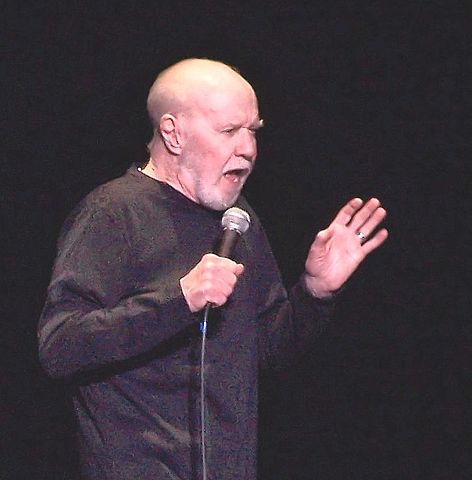

But as the years went on, and George Carlin became more popular, his hair started to grow longer. His clean-shaven face was covered by a nice, thick beard. His suits were replaced by plain, black shirts. The well-groomed, wholesome, and clean comic was slowly morphing into a scruffier, raunchier, and more cynical comedian. And he had some things to say, and he was going to say them, regardless of who got upset and what other people thought. And just like that, George Carlin became one of the loudest voices of his generation.

Class Clown

George Denis Patrick Carlin was born on May 12, 1937, in New York City, the second son of Patrick Carlin and his second wife, Mary Bearey. His family life wasn’t a particularly happy one. His father, a newspaper ad salesman, liked to get drunk and smack around those closest to him. His first wife even died of a heart attack after receiving one such beating. As far as George’s own mother was concerned, he claimed that Patrick only hit her once. Afterward, Mary’s four brothers sat him down and told him what would happen if he ever did it again…so he stopped.

Therefore, by the time George was born, the physical abuse had stopped, but his parents’ marriage still consisted of long separations interspersed with brief reconciliations. That same year, the separation became final, which made Patrick Carlin complete his downward spiral into alcoholism. He lost his family and his job, but he did enjoy a brief redemption arc before his curtain call. Around 1941, Patrick Carlin got sober, lost a lot of weight, and found a new job in radio. He moved to the Bronx, where he lived with his daughter from his first marriage, Mary, until his unsurprising death from a heart attack in 1945.

During this time, little George grew up in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, where he lived with his brother and his mother, who worked as an executive secretary. He learned to make do by himself. His mother had to work long hours to earn enough money, while his brother, who was six years older than him, often went out and left George alone. But this didn’t bother him too much. He would make a simple meal for himself and then get lost in the world of comedy, whether it was through comics, radio, or, later on, television. MAD Magazine, Ballyhoo, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, and Jackie Gleason – they were the ones who raised young George during his many hours of solitude.

From a very young age, George Carlin discovered that he was meant to be a performer. Even as a toddler, he would entertain his mother and her friends at the office with new dances or impersonations of famous actors. This garnered him the 4 As that he coveted – approval, attention, applause, approbation.

He didn’t get the same treatment in other aspects of his life. Carlin grew up in a decidedly Catholic environment – Catholic church, Catholic schools, Catholic camp, and yet, Carlin realized early on that the Catholic stuff wasn’t for him. That being said, George didn’t mind his environment. Later on, he credited the progressive nuns at Corpus Christi School for helping to shape his curious and skeptical mind by encouraging their young students to ask questions about any and all topics.

In school, George quickly adopted the role of “class clown,” and he received both competition and mentorship from another student dubbed John Pigman, a “natural performer” that Carlin claimed to idolize. Pigman could burp on cue for 4-to-5 seconds, hence his name, but his greatest act that Carlin witnessed involved Pigman walking up to two old ladies, unzipping his fly, pulling out a hot dog wiener, and then cutting it in half with a pocketknife, before running away while his audience gasped and screamed.

Unfortunately for George, as he got older, the pranks and gags were also accompanied by bouts of genuine delinquency. In the seventh grade, he got caught stealing money from a locker and, for a while, it looked like he might not be allowed to graduate middle school. Ultimately, he struck a deal with the nuns, and Carlin graduated in exchange for writing the year-end play, which was titled “How Do You Spend Your Leisure Time?”

In high school, George became a trumpeter, not because he had any particular affinity for the instrument, but because it was the only one they had in the house after his older brother stole it during a St. Patrick’s Day Parade. Other than that, high school was mostly a string of absences and detentions. George didn’t find the same relaxed and encouraging learning environment as before, so, as soon as he turned 16, he dropped out.

Carlin enrolled in the Air Force, hoping to finish his service early and then use the G.I. Bill to train for a career in radio. When he was 17, he was sent to the Barksdale Air Force Base in Bossier City, Louisiana, where he worked as a radar technician. To fill his time, George auditioned for a production of Golden Boy in Shreveport, where he met a guy named Joe Monroe, who was part owner of a radio station called KJOE. He allowed Carlin to come in for an audition, and later hired him for weekend duty, as a promo reader and substitute DJ.

To nobody’s surprise, Carlin wasn’t made for military life. He got in trouble several times for getting high or drunk on duty and for various other offenses. He wasn’t big on authority figures, either. In Carlin’s own words, when his tech sergeant chastised him for not obeying military protocol, “I told him to go f— himself. To be honest, I don’t think my salute was up to standards, either.”

Shockingly, despite his behavior, and despite being court-martialed three times, Carlin still received a general discharge in 1957. His role at KJOE had increased, but now that he was out of the air force, Carlin had no desire to stay in Louisiana. He wanted to be closer to New York, so he found a new gig with WEZE in Boston. This job lasted a whopping three months before Carlin got canned for taking the WEZE news van and driving to New York to score some weed. However, something notable did happen during his short time in Boston – he met Jack Burns, his future comedy partner.

After WEZE, both Carlin and Burns were hired by another station called KXOL in Fort Worth, Texas. Since both men had comedic aspirations, they started working on a double-act routine. In 1960, they relocated once more, this time to Hollywood, where they served as morning DJs for KDAY radio. Again, this was short-lived, because a few months later, they dropped their radio gigs altogether to focus exclusively on comedy.

Clean-Cut George

Burns and Carlin found some success playing at nightclubs in Hollywood. They appeared on The Tonight Show, which was hosted by Jack Paar at the time. They even recorded their one and only comedy album during their first year, titled Burns and Carlin at the Playboy Club Tonight, even though it wasn’t released until 1963. The act split up after two years because both men wanted to go solo, but they remained close friends.

On a personal level, George Carlin met his first wife around that time, Brenda Hosbrook. The two married in 1961 and stayed married until her death in 1997 and had one daughter together named Kelly. With the new family, life on the road became more difficult for Carlin, so he decided to settle down in New York again and focus on the comedy scene there. In fact, he went back to his old neighborhood in Morningside Heights and found an apartment in the same building where he grew up.

His budding solo career was aided by a few industry veterans who saw the potential in Carlin. One of them was Lenny Bruce, whom Carlin described as one of the few friends he had in the comedy biz. In fact, Carlin was in the audience in December 1962, when Bruce was performing at the Gate of Horn in Chicago and got raided by the police for obscenity. Carlin refused to show his ID and got arrested and tossed in the paddy wagon right next to Lenny Bruce.

Another comedian who lent a helping hand was Mort Sahl, the satirist. Jack Paar was out at The Tonight Show, and Johnny Carson was about to come in, once his old contract expired, but until then, Sahl was temporarily filling in. He convinced the NBC execs to bring in some new comedians, with anti-establishment material, and George Carlin was one of them. His first solo appearance on The Tonight Show saw him doing an impression of JFK, and it was a big hit with the audience. The television gigs started rolling in pretty steadily after that – The Merv Griffin Show, Mike Douglas, Jimmy Dean, the Kraft Summer Music Hall, and, of course, The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, where Carlin appeared over 130 times during his career. All in all, Carlin made almost 60 television appearances in 1965 and 1966, and the following year he recorded his first solo comedy album, Take-Offs and Put-Ons. Carlin would continue recording comedy albums until his death, releasing another 17 albums during his lifetime and another one posthumously.

His numerous TV appearances continued into the late 1960s, but by 1970, Carlin thought his act was growing stale. He felt like his routines were becoming too safe and bland, due to the massive influence of television on his career. By now, he wasn’t a rookie trying to break into the industry anymore. He had established himself and he thought it was time for the world to see the real George Carlin.

Seven Dirty Words

By 1970, the counterculture lifestyle was firmly embedded into the American psyche, and although George Carlin considered himself part of it, his stage persona certainly wasn’t. There wasn’t a single event that persuaded him to morph into the comedian that we all know and love. Carlin described it as a “long epiphany.” One moment happened in 1969 when he was fired from the Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas after his first show of what was supposed to be a two-year deal for saying the word “ass” during his routine. Another moment occurred when Carlin had to check into the hospital for a hernia operation and he stopped shaving during that time and decided he liked the beard. And then, of course, there was all the acid. Carlin took LSD for the first time in October 1969, at a jazz club in Chicago called Mister Kelly’s. He called it a “seminal experience” that turned him into a “radically different, utterly changed, reimprinted, reprogrammed person.” From then on, the Carlin you saw on stage was more in-line with the real Carlin – long hair, beard, wearing jeans and a t-shirt, and speaking a lot of ideas that went against “the Man.”

Not everyone was thrilled with this new & improved Carlin. Most television shows had an expectation for their comedians to be clean-cut and well-dressed. Nightclub promoters also weren’t fans of his new, edgy material. Carlin lost a lot of gigs because some places simply didn’t want to stir the pot by featuring counterculture figures. His anti-Vietnam War material, in particular, garnered him plenty of heckles and even the occasional threat from veterans in the audience. But not everyone was opposed to the change. Some show hosts such as Steve Allen, Virginia Graham, David Frost, and Hugh Hefner had no problem with this new persona, and slowly, but surely, the audience was getting used to the new George Carlin, as well.

Because the TV and nightclub appearances dwindled a bit, Carlin took the time to focus on his comedy albums. He released his second solo effort in 1972 and it was popular enough that it won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album, the first of five wins for Carlin. Titled FM & AM, it featured his classic, clean act on the AM side, while the FM side had raunchy, counterculture material, thus marking “Carlin’s metamorphosis from straight-laced to hippie.” But it would be his next album, released later that same year, that would turn Carlin into a controversial freedom of speech crusader.

Titled Class Clown, the album ended with one of the most famous (and infamous) bits in comedy history – Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television. The words that, according to Carlin, “affect your soul, curve your spine, and keep the country from winning the war.” And I know what you’re thinking. “What are these seven words, Simon?” Well, they are bleep, bleep, bleep, bleepsucker, bleep, motherbleep, and bleep.

Later that same year, Carlin was arrested for performing the routine on-stage at Summerfest in Milwaukee, just like his mentor, Lenny Bruce, before him. But this did not deter him. If anything, he doubled down on it, and Carlin recorded a sequel routine titled Filthy Words on his next album, Occupation: Foole.

Even though Seven Words became Carlin’s most well-known bit, it was actually this follow-up, Filthy Words, that got the Supreme Court involved. The saga began on October 30, 1973, when New York City radio station WBAI decided to play Carlin’s Filthy Words routine uncensored. About a month later, a man named John Douglas wrote a letter to the Federal Communications Commission or FCC, complaining that his young son heard the broadcast. He also got a non-profit media watchdog called “Morality in Media” involved, and the whole thing turned into a back-and-forth argument between the FCC and WBAI’s owner, Pacifica, over the extent of the authority that the FCC could exert on radio stations.

The whole ordeal lasted for almost five years until the US Supreme Court made a landmark ruling in favor of the FCC in the case of Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation, reinforcing the idea that the government was allowed to regulate indecent speech over the broadcast medium.

Career Highs & Lows

The controversy brought on by the court case had no negative impact on Carlin’s career who became one of the biggest names in comedy during the 1970s. In 1975, George Carlin served as host for the very first episode of Saturday Night Live, but it didn’t really leave an impression on him since Carlin was in the midst of an intense week-long drug binge at the time and his memory was left a little (purple) hazy.

There was, however, a different medium that had a major impact on his career – HBO. The premium television network wouldn’t really explode in popularity until the 80s, but it still had a dedicated audience and it offered something that nobody else did – uncensored comedy specials. The same show that you would see in a club, with all the naughty language and obscene ideas, in its entire length, just as the comedian envisioned it, delivered right into your living room. Carlin’s first HBO special was released in 1977, titled simply George Carlin at USC. It would be followed by 13 more specials, which for many people became the preferred way to enjoy Carlin’s new comedy routines over the traditional albums.

After his second HBO special aired in 1978, Carlin slowed down for a few years when it came to on-stage performances. Although this looked like a puzzling career move at the time, since he was at the apex of his popularity, he later revealed this was because he had suffered a heart attack, marking the beginning of his heart issues that would follow him for 30 years until his death.

The 1980s were a bit leaner for George, especially the first half. His health problems worsened. First, he was involved in a car crash in 1981, and the following year, he had a second heart attack, more serious than the first, while attending a baseball game at Dodger Stadium. Carlin was rushed to the hospital by limo and became one of the first people in the world to be the recipient of a new surgical technique using balloon angioplasty to open obstructed arteries.

Since the comedy clubs weren’t as packed as they used to be, Carlin thought it was the right time to renew his acting aspirations. He had always wanted to act. His first movie role came back in 1968, in a romantic comedy titled With Six You Get Eggroll, and then in 1976 he had another role in the hit comedy Car Wash. But it wasn’t until the late 80s-early 90s that Carlin received some genuine recognition for his acting. He had major supporting roles in Outrageous Fortune, starring Bette Midler and Shelley Long, and The Prince of Tides, with Nick Nolte and Barbra Streisand, but it was his role as Rufus in the Bill & Ted pair of sci-fi comedies that introduced George Carlin to a new generation of comedy enthusiasts. In television, Carlin had a few small roles and produced a pilot for HBO that never got picked up, but his longest and the most surprisingly memorable role was that of Mr. Conductor on the kid’s show Shining Time Station, based on the British show Thomas the Tank Engine. It wasn’t a role you expected from Carlin, but that may be exactly why he wanted it, and he played it for five years.

Life Is Worth Losing

The 90s and 2000s were more of the same for George Carlin – multiple HBO comedy specials interspersed with the occasional movie or television role. He had his own show for a while – The George Carlin Show, created by him and The Simpsons co-developer Sam Simon. It ran for 27 episodes but, other than that, Carlin didn’t really take on any other time-consuming projects other than stand-up comedy. He couldn’t afford them. Carlin got into trouble with the IRS for unpaid taxes and it took him a long time to dig his way out of that hole. Basically, he had to do what was most profitable which, in his case, meant touring the country and doing comedy gigs. He did not have the luxury of wasting time on an acting career that would have probably gone nowhere, but, in the end, Carlin credited his financial troubles with making him “a way better comedian.”

During this time, Carlin also tried his hand at being an author. He had already published his first book in the early 80s, but that was mostly a collection of jokes and stand-up routines. In 1997, Carlin published what he deemed his “first real book” – Brain Droppings. It became a New York Times bestseller and was followed by two more books in the early 2000s, plus a posthumous autobiography.

In 2004, Carlin checked into rehab for the first time in his life, ending a 54-year high that started when he smoked his first joint at age 13. He had already given up most drugs but was still on the wine-and-Vicodin diet and needed some help to kick this last habit. Once he completed rehab, he stayed sober for the remainder of his years.

In 2005, Carlin accepted a new Las Vegas contract at the Stardust. It wasn’t Carlin’s first Vegas engagement, and these gigs always placed him in a quandary. On one hand, Carlin absolutely hated Las Vegas, which he called “the most dispiriting, soul-deadening city on earth.” In fact, he had just been fired from his previous Vegas contract at the MGM in 2004, right before checking into rehab, because he kept insulting his audiences for being stupid enough to come to Vegas. On the other hand, Carlin admitted that it was a great place for a comedian to work on new material. Fresh audiences came to him every night, he didn’t have to travel, the money was good, and a lot of people in attendance weren’t his fans, they just received comped tickets, so they weren’t going to laugh just to humor him.

Carlin worked on his last two HBO specials here, with the final one, It’s Bad for Ya, coming out just a few months before his death. On June 18, 2008, Carlin was awarded the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor by the Kennedy Center. “Thank you Mr. Twain. Have your people call my people,” Carlin responded in a statement. Five days later, he died of heart failure, aged 71. He had just performed a show a week earlier and he had already begun work on his next HBO special and was also writing a one-man Broadway show called Watch My Language. When George Carlin was asked in interviews why he kept working so hard in his old age, he liked to quote master cellist Pablo Casals who said: “Well, I’m beginning to notice some improvement.”