New York Assistant District Attorney Abraham Rorke described Fritz Duquesne as “one of the most desperate and daring criminals we have ever had here. His adventures read like a romance.”

The Daily Mail decried Duquesne as a notorious scoundrel wanted for “murder on the high seas; the sinking and burning of British ships; the burning of military stores, warehouses, coaling stations, conspiracy, and the falsification of Admiralty documents.”

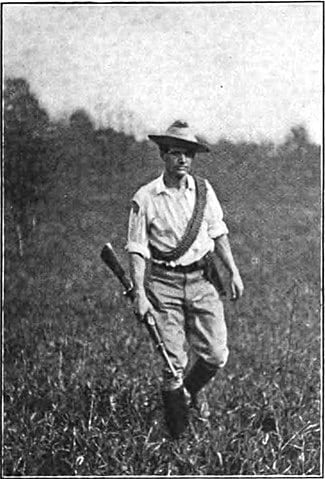

And that’s just the cliff notes version. Duquesne started off as a big game hunter in Africa. Then he became a commando during the Boer War, responsible for countless assassinations that earned him the moniker of “the Black Panther of the veld.” Then in the First World War, he turned saboteur, responsible for the bombing of several ships, and, finally, in World War II, he established a powerful spy ring to help out Nazi Germany.

He did all of this to torment Great Britain. To put it simply, there was nothing that Duquesne would not do in order to persecute the British. Find out what motivated his undying hatred as we take a look at the life of a man whose exploits read like something plucked out of the pages of a pulp magazine – this is the story of the South African adventurer Fritz Duquesne.

Early Life in Africa

Frederick “Fritz” Joubert Duquesne was born on September 21, 1877, in East London – not the one in England, but rather the city on the southeastern coast of South Africa, in what was back then a self-governing British colony called Cape Colony.

His parents, Abraham Duquesne and Minna Joubert, were Boers, referring to South Africans descended from European settlers. In their case, both had French Huguenot ancestry. Fritz said that his mother was related to Piet Joubert, the Commandant-General of the South African Republic and a war hero to the Boers, but then again, Fritz said a lot of things throughout his life. The man spent decades in numerous careers, using dozens of fake identities and making countless incredible and unsubstantiated claims. Knowing exactly which ones were true and which ones were false became an almost impossible task that not even his biographers could pull off.

Anyway, when Fritz was young, his family moved to Nylstroom, today the town of Modimolle in South Africa, where they purchased a farm. This was in the South African Republic which, at the time, was an independent state. The household consisted of Fritz, his parents, his two younger siblings, Elsbet and Pedro, and their great uncle Jan.

Abraham Duquesne worked as a farmer, hunter, and trader, and took Fritz along on hunting trips from an early age, teaching him valuable survival and killing skills out in the African veld. When he was only 12 years old, Fritz killed his first man in self-defense. The family used the main room of their house as a trading post and one day, while Abraham was away, a Zulu customer got into an argument with Fritz’s mom over the prices. When he became violent, Fritz rushed him, grabbed the man’s assegai spear, and stabbed him through the stomach.

The following year, 13-year-old Fritz went to school in England. He studied civil engineering after graduation until he joined up with a conman named Christian de Vries and started traveling around the world, swindling people from town to town. His father found out about this and put a stop to it when he finally caught up to Fritz in Singapore.

The young man spent a few more carefree years just lounging around Europe, but the easy times would soon end forever. In 1899, the 21-year-old had to return to his home in South Africa, where he developed his fanatical hatred of the British that would dominate the rest of his life.

The Black Panther of the Veld

In 1899, the Second Boer War erupted between the United Kingdom and two independent Boer states called the South African Republic and the Orange Free State. Ostensibly, the causes for the war were varied and complex, as the conflict had been brewing for almost a century but, realistically, it all boiled down to gold and diamonds. The Boers had them and the British wanted them.

As you could tell from the name, there was also a First Boer War back in 1880. However, that was a relatively quick affair that only lasted for three months, resulting in a Boer victory with only a few hundred casualties. By comparison, the Second Boer War was longer and much, much more brutal, as the British employed scorched earth policies and concentration camps to counter the guerilla warfare used by the Boers.

Although Duquesne had made England his adopted home, he did not hesitate to return and fight for the South African Republic. Soon after joining the war, he took part in the Siege of Ladysmith in November 1899, where he received a gunshot wound to the shoulder followed by a promotion to artillery captain. The injury couldn’t keep him down for long, though, and by December, he had healed enough to fight in the Battle of Colenso, where he was taken prisoner for the first time. This did not prove to be much of an obstacle for Duquesne, as he turned out to be a master escape artist. POW camps could hardly contain him for long, as he was captured several times but always managed to get away.

During a return trip to the farm where he grew up, Duquesne discovered the gruesome fate that befell his family at the hands of the British army – the whole place had been burned to the ground, his sister had been raped and shot in the back, his uncle left to hang from a telegraph pole, and his mother had been kidnapped and sent to a concentration camp. That was the pivotal moment that changed his life forever… the moment that Fritz Duquesne decided to spend the rest of his years inflicting as much pain and suffering as possible on Great Britain and its people. His greatest hatred was reserved for General Herbert Kitchener, who was the commander-in-chief of the British forces in the Boer War and was the one who enacted the ruthless scorched earth policy.

Duquesne discovered that his survival skills made him perfect for guerilla warfare, and soon enough he was leading his own commando unit, responsible for a lot of sabotage, explosions, and stealthy assassinations. His ability to strike without being seen earned Duquesne the nickname “the Black Panther of the Veld” and he soon turned into public enemy #1 for the British, who wanted him dead and buried. They even tasked one of their best scouts, American officer Frederick Russell Burnham, to track down and kill Fritz. Burnham failed to do so and later described his experience in his memoirs. He said:

“There were only two men on the veld I feared, and one was Duquesne…Much has been written about Duquesne, most of it rubbish. Yet his real accomplishments were so terrible… they make the yellow journal thrillers about him seem as mild as radio bedtime stories…” He was “the greatest scout the Boers produced… He was one of the craftiest men I ever met. He had something of a genius of the Apache for avoiding combat except in his own terms; yet he would be the last man I should choose to meet in a dark room for a fight to the finish, armed only with knives.”

Around this time, we get, arguably, the most popular legend which involved Duquesne, that of the notorious Kruger Millions. The story goes that the President of the South African Republic, Paul Kruger, had a gigantic hoard of gold shipped out of the capital to a safe location to avoid having it fall into British hands, with Duquesne in charge of one of the shipments. While passing through Portuguese East Africa, or Mozambique as we call it today, the other soldiers tried to double-cross Duquesne and steal the gold for themselves. A fight ensued where Duquesne, once again, proved why he deserved his fearsome reputation. He killed them all and had the porters hide the gold somewhere safe, but never returned to recover it. Since then, the legend of the Kruger Millions has spread far and wide, and many people have spent years searching for the lost treasure.

Duquesne eventually made his way to the frontlines again and took part in the Battle of Bergendal, in August 1900. This ended up being the last pitched battle of the war, even though the conflict continued for two more years. Following another British victory, Duquesne and his men had to retreat into Mozambique. Fritz was captured again and sent to an internment camp near Lisbon, but just like before, this was just a small detour for him. Duquesne escaped again, this time by allegedly seducing the daughter of one of the guards.

From this point on, we can honestly say that Duquesne embraced his new career as a spy and saboteur, as a man with a dozen different identities who would never go back to the simple life he once had in the grasslands of Africa.

Going to America

After he fled Portugal, Duquesne did not return to South Africa. Instead, he did something incredibly ballsy, even for him – he marched straight into the belly of the beast, traveling to England and joining the British army. We’re not sure how exactly he pulled it off, but thanks to his school years spent in Britain, he had lost his South African accent and instead sounded like a posh Englishman. Some say he simply presented himself as a Boer defector; others think that Fritz had fake papers and used them to craft a new identity for himself.

Anyway, in 1901 Duquesne returned to Cape Town, this time as an officer with the British forces. Some accounts say that Duquesne used his British credentials to track down the location of the concentration camp where his mother was held. He went there and he found her…half-dead, starving, and infected with syphilis from repeated sexual assaults. He couldn’t just walk her out without raising questions, so he had to leave her behind, knowing that he would never see her again. Duquesne temporarily satiated his lust for revenge by killing two British captains that he passed on his way out of the camp.

Assuming any of that actually happened, Duquesne then spent some time building up a network of Boer sympathizers and developing a list of valuable targets to destroy. As much as he enjoyed spilling British blood, he probably realized that he could do more damage by blowing up bridges, munition dumps, power plants, and the like. However, he never acted on his plans because he was betrayed by one of his co-conspirators, and the entire network was arrested. Everybody else was sentenced to death and executed, but Fritz avoided his date with the firing squad by supplying the English with secret Boer codes for communication. Later, Duquesne always insisted that the codes he provided the enemy were fake, but for now, he found himself imprisoned in a 17th-century Dutch fort called the Castle of Good Hope. Unsurprisingly, he immediately went to work on his escape, as he intended to dig out the stones using a spoon. His plan was discovered, though, so Duquesne was sent to a penal colony in Bermuda that had been repurposed as a POW camp for Boers.

This time, Fritz did not make it out so easily. It wasn’t until June 1902 that he managed to escape the island and secure passage on a ship with the help of members from the Boer Relief Committee. By that point, the war was over, with a decisive victory for the British, but this did nothing to diminish the hatred that Duquesne still felt in his heart. However, there was nothing (and nobody) left for him in South Africa so, instead, he sailed to America to start a new life.

Alice Wortley Duquesne, 1913.

In the US, Duquesne landed in Maryland and then made his way to New York City. He still wanted to get revenge on the British, but now that the war had ended, there wasn’t much demand for sabotage or commando work. Instead, he needed to bide his time and wait for the right opportunity to come along. Until then, Duquesne needed a job and he found employment with the New York Herald. At first, he was simply a bill collector, but his knife-edge stories of hunting and adventuring out in the wilds of Africa proved popular enough that Duquesne was hired as a contributing writer; he was then made a regular reporter and, by 1906, he was the Sunday editor for the Herald.

Undoubtedly, like all other things in his life, Duquesne’s exploits out in the veld had been heavily sensationalized, but they found a captive audience, which included one hunting enthusiast named Teddy Roosevelt, who happened to be President of the United States at the time. Roosevelt’s admiration scored Duquesne an invite to the White House in 1909, where the two talked big game hunting and Fritz advised Teddy on a safari he wanted to undertake.

This is the perfect time to mention the strangest moment in Duquesne’s career which, for a man like Fritz, is really saying something. In 1910, he became one of the driving forces behind a new movement taking root in America to introduce the hippopotamus to Louisiana in response to a meat shortage. Duquesne testified as an expert before the Committee of Agriculture and advocated for the importation not only of the hippo but other animals such as the giraffe, the yak, the koodoo, the springbok, and many others. If Duquesne and others had their way, then today Louisiana would be teeming with African wildlife and you’d have to be on the lookout for charging hippos while fishing in the Mississippi Delta. And if that’s not weird enough, one of the other main proponents of the bill was Frederick Russell Burnham, the same scout who had once been tasked with tracking down and killing Duquesne. Unfortunately, the bill did not pass and Louisiana remained hippo-free.

When he wasn’t writing, Fritz traveled to war zones as a correspondent and gave lectures around the country. He married a woman named Alice Wortley in 1910 and became a naturalized American citizen in 1913. The marriage only lasted eight years, but if he wanted, Duquesne could have built a really nice life for himself in America, if he could just let go of the past. But his hatred still consumed him, so he jumped at the opportunity to cause more chaos and suffering to the British provided by the advent of the First World War.

Sabotage in South America

We don’t know if Duquesne volunteered or was recruited, but he became a secret agent for Germany during World War I. Fritz had no particular ties to the country prior to the war, but going by the old adage of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” as long as they fought the British, that made them alright in his book. As a bonus slap in the face to Duquesne, the famous British recruitment posters that showed the mustachioed officer, pointing a finger saying stuff like “Your country needs you” featured none other than the country’s new war minister, the man Duquesne hated more than any other person on the planet, Lord Kitchener.

Duquesne was mainly active in South America during World War I, sabotaging ships on their way to Britain. He traveled from one country to another and switched identities often to avoid detection. His basic strategy involved sending boxes that were allegedly filled with “mineral samples” and “orchid bulbs” back to England. In reality, the boxes were packed with timed explosives, which were set to detonate during their voyage across the Atlantic. Duquesne bragged that he sunk 22 ships using this method, and while he was certainly responsible for several explosions, that number is impossible to verify.

His coup de grâce came in February 1916, when Duquesne set the SS Tennyson on fire by placing onboard a trunk filled with highly flammable film celluloid, plus some explosive to ignite it. Adding insult to injury, Fritz also tried to make some extra money on the side by taking out an insurance policy on the film, which was a valuable commodity back then. His brazen gamble didn’t pay off and he was discovered when he tried to cash it. The British had now put a bounty on his head for the death of three seamen aboard the Tennyson, but Duquesne tried to evade it by faking his own death. In April 1916, newspapers around the world reported a story that Duquesne had been killed while fighting in Bolivia. The ruse only lasted for a few weeks, as he was spotted and recognized, but the confusion surrounding his untimely demise gave the Boer captain enough time to flee South America and make it to Europe.

We arrive now at Duquesne’s most boastful, but also most doubtful claim – that he was the one who killed his archenemy, Lord Kitchener. We know, for a fact, that Lord Kitchener died on June 5, 1916. He was one of over 700 people who perished when the HMS Hampshire hit a German mine on its way to Russia and sunk in the cold waters off the coast of Scotland. But according to Duquesne, he was working with the Germans on this hit. He said that he was on board the ship during that fateful voyage, disguised as a Russian official and that he dropped water torches over the side so that the German U-boats would know where to plant the mines. He then jumped overboard into a waiting raft and was collected by a submarine and taken to Germany where he received the Iron Cross. No German records survive to verify this claim, so maybe take this one with a grain of salt.

Whether or not that happened, we can’t say for sure, but Duquesne eventually made his way back to America, except that now he styled himself as an Australian veteran named Captain Claude Staughton. He kept the act going for a while, but New York authorities eventually found out his true identity and arrested him by late 1917. This wasn’t for any bombings or assassinations, mind you. After all, America wasn’t even involved in the war when any of those took place, so why would they care? Instead, Duquesne was indicted on insurance fraud for trying to claim the losses he “sustained” following the Tennyson explosion. He was also publicly outed as a spy, as he possessed a letter from the German consul thanking him for rendering “notable services to our good German cause.”

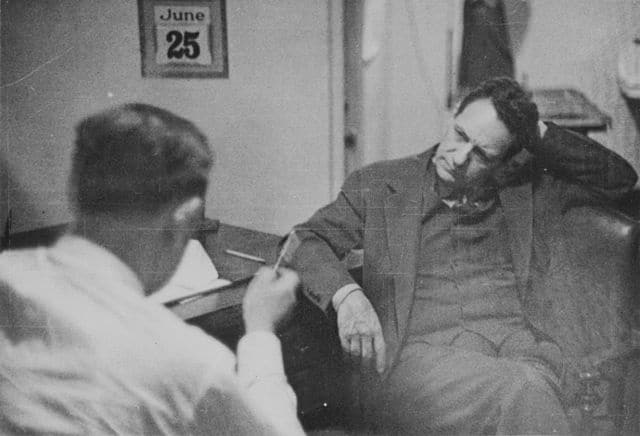

As you might imagine, the British really wanted to get their hands on him and requested that he be extradited to stand trial for murder. While the whole process was being worked out, Duquesne tried a classic strategy – feigning insanity. This might work in legal dramas, but it’s surprisingly ineffective in real life, and nobody bought it. After a few months, he switched up his tactic and collapsed in the middle of the courtroom, claiming to be paralyzed from the waist down. Obviously, everyone called “shenanigans,” but several doctors looked him over, and he passed all of their examinations. He didn’t even flinch when one of them stuck needles under his toenails. Ultimately, people bought the ruse, and Duquesne was sent to the prison ward of Bellevue Hospital.

What followed was an Oscar-worthy performance, as Fritz went full “method” and spent the next months in a wheelchair, pretending to be paralyzed at all times, but sawing through the bars of his cell whenever he wasn’t being watched. On May 26, 1919, only a few days before his extradition to Britain to stand trial for murder, Duquesne made his escape.

The Spy Ring that Never Was

Following his escape from Bellevue, Fritz Duquesne remained a free man for the next 13 years. This part of his life remains poorly documented. He probably fled to Mexico immediately after leaving the US, but we only know of his movements for sure starting with the late 1920s. He probably should have avoided the United States altogether, given that he was a wanted man, but Fritz just couldn’t resist the glitz & glamor of New York City, so he returned under the new identity of Frank de Trafford Craven. He found a job working for businessman Joseph P. Kennedy, father of future president John F. Kennedy, on the publicity staff of his new film production company, RKO Studios.

In 1932, Duquesne got arrested again, even though he kept insisting that he was Frank de Trafford Craven. His arrest was followed by a prolonged and complicated trial that involved both the US and Britain since extradition can often turn into a bureaucratic nightmare. Ultimately, Britain decided that Duquesne just wasn’t worth it, so they dropped the request. Once again, Fritz was a free man with no legal troubles, allowed to get on with his life. You would think this whole episode might have encouraged him to live & let live, but not Fritz Duquesne. When Nazi Germany came calling, Duquesne answered the call.

In 1937, Fritz began working for the Abwehr, the German military intelligence service, and started developing a network of spies who could either obtain valuable secrets or carry out acts of sabotage. All of this was done with the foresight that, eventually, the United States would go to war against Germany. By 1939, this network numbered over 30 people, all placed in key positions around the country, and it became known as the Duquesne Spy Ring, named after its ringleader. However, it did not get a chance to do any serious harm, as the FBI broke up the spy ring before America even joined the war.

As it turned out, one of the men inside the network was not that keen on the nazis. His name was William Sebold and, even though he was born in Germany, he became a naturalized American citizen and sided with his adopted homeland. He initially joined the spy ring following pressure from high-ranking Nazi members while on a trip to Germany, but once he was back on American soil he went to the FBI and told them everything. With his information, the authorities arrested Duquesne and 32 other spies, who were later sentenced to a total of over 300 years in prison.

Fritz Duquesne’s days of adventure, chaos, and violence were officially over. His trial occurred shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, so American sentiment was heavily against traitors. Duquesne was sentenced to 18 years in prison and he served 12 before being released in 1954. By that point, he was an old, broken man in poor health following a stroke that left him partly paralyzed. He returned to New York City again where he was placed in a nursing home.

On December 21, 1955, Duquesne gave a final speech at the Adventurers Club, even though many members refused to attend due to his occasional bouts of treason. It proved to be one last chance for him to reminisce on the bloody and daring exploits of his youth. Fritz Duquesne died of another stroke a few months later, on May 24, 1956, aged 78, leaving behind a complicated legacy. Some people saw him as a brave hero, others a villain and a madman; some thought he was an incredible adventurer while others decried him as a fraudster and a liar; some considered him a cold-blooded murderer, and others an agent of righteous vengeance. All his life, Fritz Duquesne divided opinions, and will probably continue to do so for the foreseeable future.