Cornelius Vanderbilt wasn’t exactly what you would expect out of one of the richest men in the world. He was brutish, ill-mannered, barely literate, and swore like a sailor. But, perhaps, it was these same traits that made him the definition of the American Dream with all the good and the bad that that entailed. He rose up from nothing; from less than nothing, in fact. His Dutch ancestors came to the New World as indentured servants. But through hard work and a keen eye towards the future he amassed a fortune seldom seen before that time.

That being said, he certainly was no saint. Like all the other industrialists and speculators of his time, Vanderbilt stepped on plenty of toes to make his money. He was ruthless in business and didn’t come to be regarded as America’s first robber baron for nothing.

Early Years

Cornelius Vanderbilt was born on May 27, 1794, in Staten Island, New York City, to Cornelius Van Der Bilt Sr. and Phebe Hand. His ancestors had come to North America 150 years before he was born, back when the territory was still part of a Dutch colony called New Netherland. His great great great grandfather was a man named Jan Aertsen who immigrated to America as an indentured servant. By the time Cornelius was born, his family’s station had improved, but not by much. His parents were farmers and, to supplement their income, his father also operated a ferry that transported people and goods across the New York Harbor.

Young Cornelius had a very strong work ethic ever since he was a boy. He labored on the farm from an early age and, when he was 11 years old, he dropped out of school to work full-time. Although, clearly, things would work out well for him, his lack of a formal education would haunt Vanderbilt for the rest of his life. Even in his later years, he struggled to write English fluently and he was in the habit of spelling words out phonetically. It was part of the reason why he could never find acceptance within the ranks of the wealthy elite and was always regarded as a boorish outsider.

Cornelius Vanderbilt might be remembered today as a railroad tycoon, but it wasn’t trains that made him his first fortune, but rather ships. His road to success started when he began helping his father with his ferry service. He learned the business and, by the time he was 16, Vanderbilt was ready to branch out on his own. He borrowed $100 from his parents to buy his own ship, a two-masted sailing vessel called a periauger, and he paid them back by splitting the profits with them. Vanderbilt faced stiff competition, but his strategy was to undercut everyone else by offering cheap fares for transport between Staten Island and Manhattan. That being said, he was also an extremely hard worker and constantly reinvested in his business by acquiring more ships.

Vanderbilt quickly built up a reputation as a reliable and assiduous ferryman. In fact, even though he was still just a young man, he earned the nickname “The Commodore,” a moniker which he eagerly embraced and used for the rest of his life. Thanks to his good standing, Vanderbilt earned an important government contract in 1812 when war broke out between the United States and the United Kingdom to supply the forts and ferry soldiers around New York Harbor.

This period of conflict proved quite prosperous for Cornelius Vanderbilt. On the personal front, in 1813 he also married his first wife, a cousin named Sophia Johnson. They would go on to have 13 children together, although they did not have a happy marriage. By all accounts, Vanderbilt was not a very caring father or husband. It had often been rumored that he regularly cheated on Sophia with prostitutes and even had her committed to an insane asylum once.

Even though he was steadily amassing a small fortune as he was building up his fleet, in 1817 Vanderbilt was offered a position he couldn’t refuse – that of steamboat captain. For years, the Commodore had developed an interest in steam-powered ships as he considered them superior to sailing vessels and the way of the future. Moreover, the offer came from Thomas Gibbons, former Mayor of Savannah, Georgia, and one of the wealthiest merchants around.

Vanderbilt assumed command of the steamboat Mouse and started ferrying people between New York and New Jersey while, simultaneously, maintaining control of his growing business. However, he soon discovered that the steamboat trade in New York was run by a monopoly granted by the New York State Legislature to two men: Robert Livingston, an influential New York politician and one of the Founding Fathers; and Robert Fulton, the man credited with inventing the first commercially-viable steamboat. They were both dead by 1817, but their heirs still had a vise-grip on the monopoly and they had granted a license to run steamboats on the Hudson River to former New Jersey senator and governor Aaron Ogden.

This whole thing started from a personal rivalry between Gibbons and Ogden. At first, the former tried to bankrupt the latter by undercutting his prices. Eventually, Ogden sued and the matter went to court where it actually resulted in a very important, landmark ruling. In the case of Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Supreme Court concluded that the commerce clause in the Constitution which granted the federal government the power to decide how interstate commerce was conducted also extended to waterway navigation. Therefore, the state of New York had no right to grant a monopoly in the first place, and the court ruled in favor of Gibbons.

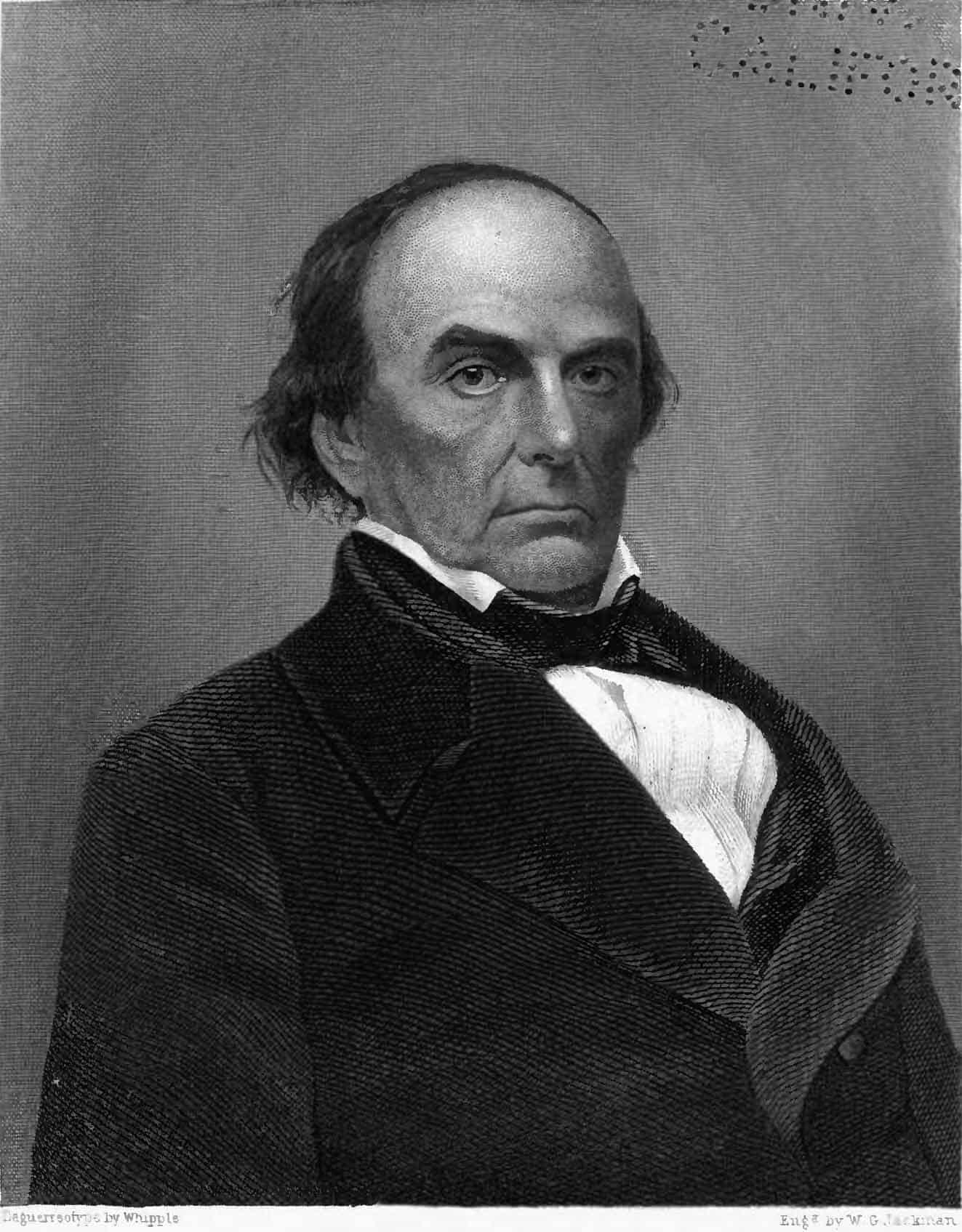

To support his employer, Vanderbilt had his own case against Ogden, even hiring Daniel Webster, a noted statesman, to argue his case before the Supreme Court. However, it was never heard as it was unnecessary after the ruling in the previous case. Even so, Vanderbilt deserves no credit as some sort of pioneering trustbuster. He only fought the monopoly because it worked against him. In the future, he would have no problem using them to his advantage.

The Birth of an Empire

In 1826, Thomas Gibbons died, leaving his business in the hands of his son, William. Cornelius Vanderbilt considered the wealthy merchant as somewhat of a mentor to him, but he didn’t like William as he considered him weak. He stayed on for a few more years until he got his finances in order, but Vanderbilt left the business in 1828 and broke off on his own again. He even bought his own steamboat – a 145-ton, 106-ft sidewheeler called the Citizen.

This vessel was quickly followed by others in the next few years. As we previously mentioned, Vanderbilt regularly took the profits he made and reinvested back into his business, steadily building a fleet of steamboats and opening new routes for his ferries such as the Long Island Sound, Albany, Connecticut, and Providence. Of course, he faced competition in all the new areas he expanded to, but these companies usually found out quickly that it was dangerous to go against the Commodore.

He was ruthless when it came to business. Because he had a wealth of resources, his go-to strategy involved undercutting his opponents’ prices, oftentimes to the point where they would either go bankrupt or be forced to sell to him. In the cases of some companies that also had deep pockets, they would often pay Vanderbilt large sums of money to leave the area and take his ferries on another route.

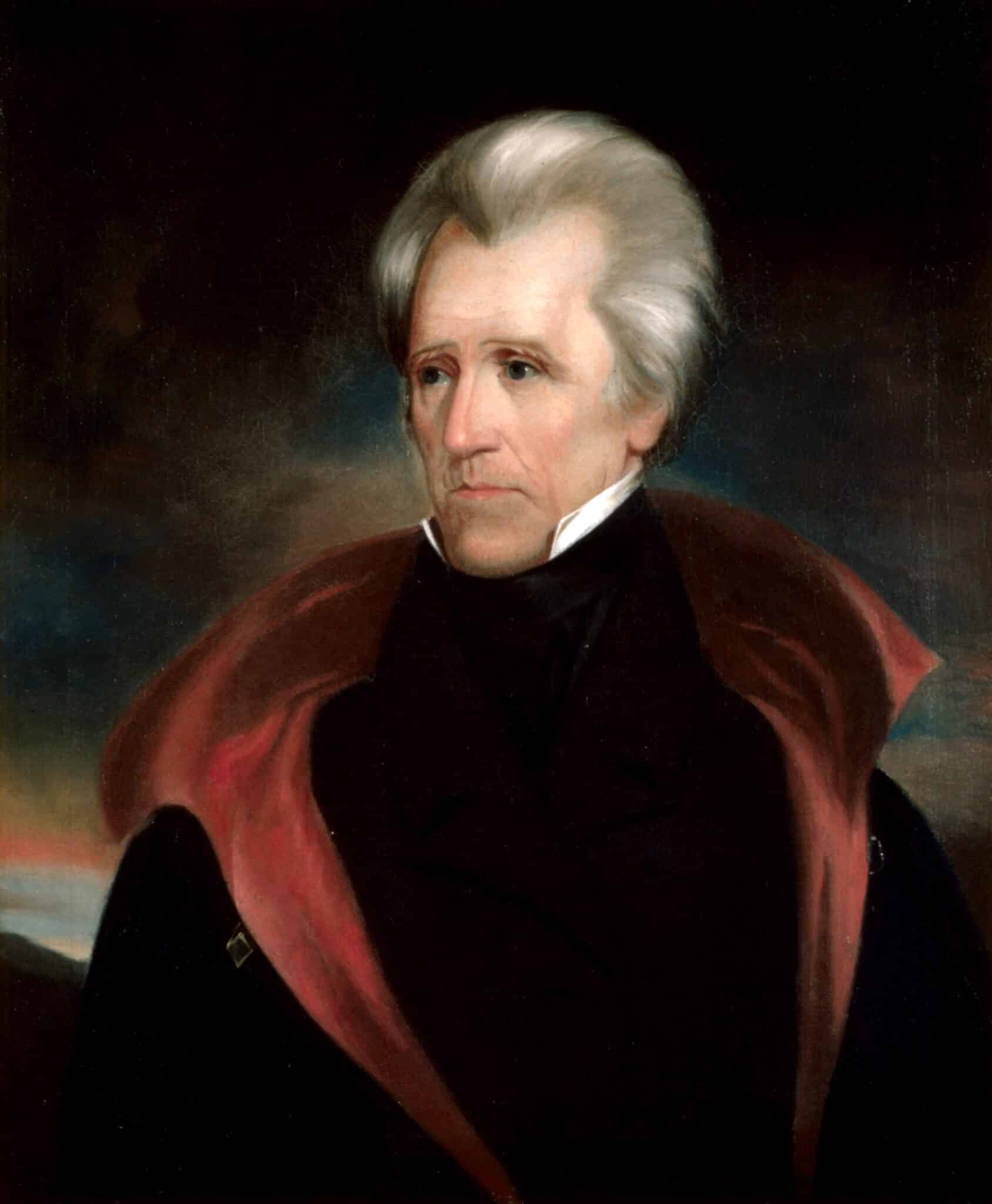

One notable example was when the Commodore wanted to put his ships on the Hudson River, traveling between New York City and Albany. This route was dominated by a monopoly called the Hudson River Steamboat Association, but Vanderbilt only saw it as a challenge. This was at a time when Andrew Jackson was running a populist presidential campaign based around “the common man.” He had gained popularity by portraying himself as a man of the people, fighting the corrupt aristocracy. Vanderbilt did the same thing. It wasn’t hard, after all, he did come from a working class family and his behavior and demeanor were certainly more at home in a bar than a banquet. He dubbed his ferry service the “People’s Line” and offered cheap rates that working men could afford. Unsurprisingly, this strategy worked really well and, soon enough, the Steamboat Association offered him $100,000 to leave the Hudson River, plus another $5,000 a year to stay away.

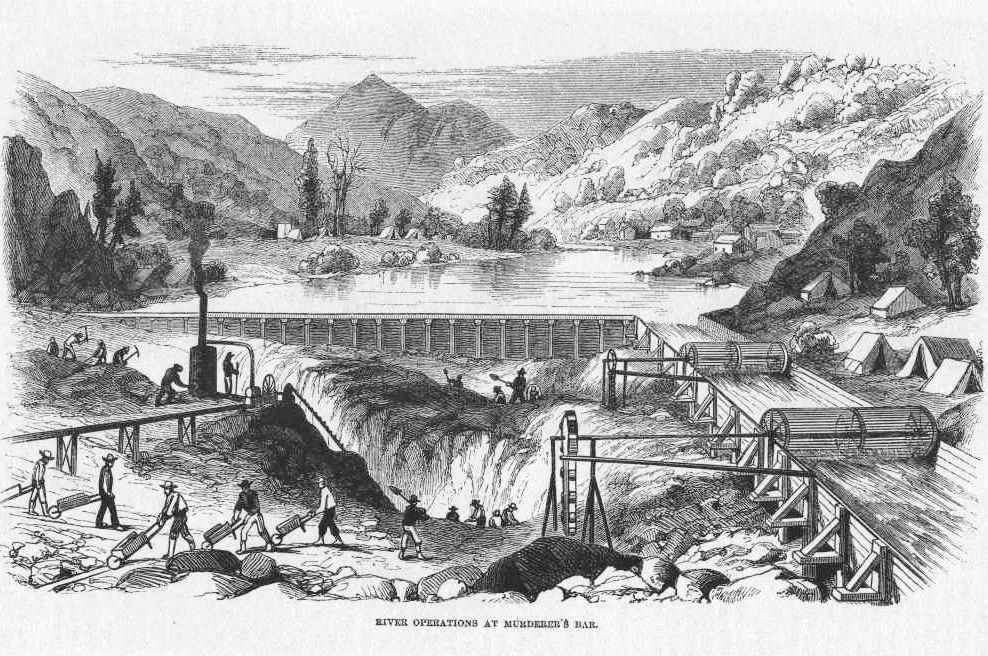

Going into Nicaragua

For years, Vanderbilt focused his business mainly in the region between Boston and New York, but he organized a major expansion in 1849 prompted by the California Gold Rush. He knew that hundreds of thousands, even millions of people would be traveling that way, many of them looking to settle permanently in the unorganized California territory which, at that point, was still lobbying for statehood. When California finally became a state in 1850, demand for transportation between the East and West Coasts skyrocketed and, all of a sudden, a new multi-million dollar venture was born.

Unsurprisingly, Vanderbilt wanted a piece of that pie and started sending steamships along this route. Back then, the only way to travel from New York to San Francisco by water was to round Cape Horn at the southerly tip of South America. However, this trip was long and time meant money. It was still quicker and less dangerous than traveling overland across the United States, but Vanderbilt sought a way to speed up the journey even more.

The solution was a canal across Nicaragua. It would have shaved days off each trip. Vanderbilt even founded the Accessory Transit Company or ATC whose purpose was to secure transportation across the Central American country. However, for various political and economical reasons, the project never went into construction and, eventually, it was established that a canal across Panama would be more efficient.

That being said, the ATC was not a failed venture. Quite the opposite, in fact. Vanderbilt may not have been able to secure a route that took passengers from the East Coast to the West Coast on a single ship, but he developed a course that was a mix of land and water travel. His customers would board a steamboat in New York which took them to the eastern coast of Nicaragua. From there, the goods and passengers were loaded onto smaller vessels capable of going up the San Juan River and crossing Lake Nicaragua. When they reached land, they traveled by stagecoach to the western coast where they boarded a different steamer headed for San Francisco.

It was the fastest and cheapest way of reaching the East Coast and it made Vanderbilt a nice bundle of money, but he didn’t get everything he aimed for. What the Commodore wanted was a big, fat government contract to also transport mail, but it went instead to some of his competitors who founded the Pacific Mail Steamship Company and the United States Mail Steamship Company. Even so, the Commodore still had an ace up his sleeve as his opponents used a route across Panama. It was similar, but longer, so Vanderbilt went back to his tried-and-true method of slashing his prices to steal all of his competition’s clientele. It worked, but when Gold Rush fever started to die down, the Commodore saw no reason to keep this route so he accepted a large monthly stipend from his opponents to close down the ATC.

The War of the Commodores

While Vanderbilt was expanding his operations to the West Coast, he also started offering transatlantic journeys to Europe. Again, this venture proved profitable, but the Commodore also learned that not even he was infallible. As before, his new route had competition – the British Cunard Steamship Line, among others. Vanderbilt tried to squash it like he always did, but failed. The British government was keen to see the company succeed against American and German firms so they provided a low-interest loan plus a generous annual subsidy to ensure that the Cunard Line had the capital to both build top-of-the-line ships and to compete with Vanderbilt’s undercutting tactics.

Another unexpected setback occurred in 1853 when Vanderbilt saw fit, for the first time ever, to take a vacation. He was almost 60 years old and had been working for most of his life so the Commodore decided that, if he were to go on holiday, he would do it in style. Vanderbilt bought a giant, luxurious yacht he dubbed the North Star and took his whole family on a grand tour of Europe, at a total cost of half a million dollars.

Whilst he was vacationing, the Commodore left the management of ATC in Nicaragua in the hands of two men, Charles Morgan and Cornelius Garrison. In came another American named William Walker who was a filibuster which, back then, meant that he was a sort of insurgent who would rally troops to invade parts of Latin America, take over by force and set up English-speaking colonies. There were a few filibusters during the 19th century as Manifest Destiny was still a big thing, but Walker was probably the most famous of them all because he actually succeeded twice…sort of.

First, in 1853, Walker and dozens of his followers invaded Mexico and actually conquered the Baja California Territory by assaulting its capital of La Paz and capturing the governor. He then declared it the Republic of Lower California, a sovereign state with him as president. Of course, it didn’t last long. As Walker and his men ran out of supplies, desertions became frequent and he also had to relocate his headquarters several times because the Mexican army was just a little upset with him. In the end, he had no choice but to cross the border and surrender to an American army. He was arrested and charged with an illegal war, but was actually acquitted after giving an impassioned speech that swayed the jury.

All Walker learned from this experience was that he needed better financing. In 1855, he was ready to try again, this time in Nicaragua. While the Commodore was still on his extended vacation, Walker approached Morgan and Garrison and, in exchange for their support of his coup, he promised that, once he was the new president, he would revoke ATC’s charter and issue a new own in their name. And that’s exactly what happened. In 1856, William Walker became the new President of the Republic of Nicaragua and a new transit business owned by Morgan and Garrison had exclusive rights to operate in the country.

Understandably, Vanderbilt was furious when he learned of their treachery. According to an apocryphal story, he wrote them a short and ominous letter where he said “Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I’ll ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt.”

And that is, pretty much, what he did. He set up another transit company that passed through Panama with dirt cheap prices to steal their customers. He refused to take any passengers to or from Nicaragua and convinced the nearby Central American countries to not recognize Walker’s government. Back in the United States, he sued Morgan and Garrison in a legal battle the American media dubbed “The War of the Commodores.” And, most decisively, he sent agents into Nicaragua to cause chaos and convince the locals to rebel against Walker. It worked and, in 1857, the filibuster surrendered to the U.S. army again. Meanwhile, Morgan and Garrison’s business went bankrupt and Vanderbilt assumed control over the region’s transit system again.

As far as Walker was concerned, he once again was acquitted as many Americans regarded him as a hero. Then he went and tried the same thing in Honduras, but things went a little different that time. The Honduran authorities captured him and, in 1860, executed him by firing squad.

From Ships to Trains

The 1860s were a troubling time for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as they were for most Americans, because of the Civil War. On a personal level, he suffered losses. His youngest and favorite son, George Washington Vanderbilt, died in the war after contracting malaria. An inveterate misogynist, the Commodore never showed much affection to his daughters and he considered his other two sons to be disappointments. One of them, Cornelius Jeremiah, was a degenerate gambler who was on bad terms with his father after the elder Cornelius locked him up in a lunatic asylum. The other one, William Henry, the Commodore simply regarded as weak and good for nothing. Eventually, Vanderbilt changed his tune about William after he took a poor farm in Staten Island and made it profitable. Since then, Vanderbilt integrated his son more and more into his business and, eventually, it was William who inherited most of his father’s estate.

In 1868, Vanderbilt’s wife, Sophia, died. After her passing, the Commodore began visiting mediums, particularly the Claflin sisters. He fell in love with the younger sibling, Tennessee Claflin, and, according to some sources, even proposed marriage. This worried his family who were concerned that Vanderbilt might leave his fortune to a stranger so they played Cupid and fixed him up with a distant cousin who was four decades younger than him. This cousin had an unusual name for a woman. She was called Frank Armstrong. We’re not exactly sure why, but at least one historian asserts that this was due to a misguided promise from her parents to a close friend to name their first child Frank, even if it wasn’t a boy. Anyway, Cornelius and Frank eloped in Canada in 1869.

As far as the Claflin sisters were concerned, they soon gave up their spiritualist ways and became noted suffragists. With Vanderbilt’s backing, they also got into the business world and became the first women to open a brokerage firm on Wall Street. The older sister dropped the “Claflin” from her name and became known as Victoria Woodhull, the first-ever female candidate for the Presidency of the United States.

Going back to the Civil War, this period represented a huge shift in Vanderbilt’s business practices. No longer impressed with the capabilities of steamboats, he now looked to the railroad as the future. Truth be told, the Commodore had shown interest in trains for decades. He might have invested in them even sooner if not for his involvement in one of the first fatal train accidents in American history. All the way back in 1833, the Hightstown Rail Accident occurred in New Jersey when a carriage caught fire, caused an axle to break and derailed the train. One person was killed and dozens were injured. Among them was Cornelius Vanderbilt who broke his leg in the crash.

In the decades following that event, the Commodore only had minor dealings with the rail industry. He occasionally bought shares in new railroads, but most of his efforts were concentrated in Nicaragua. Eventually, though, he could no longer ignore the potential for huge profits offered by this new mode of transportation. Starting with the late 1850s, he began selling off his fleet of ships. During the Civil War, he even donated his most prized vessel, the appropriately-named Vanderbilt, to the Union Navy to use against the Confederates who dominated the seas with the help of their ironclads. Vanderbilt even acted as advisor when it came to all things maritime, but he refused an official position in Lincoln’s cabinet as he wanted to avoid politics at any cost.

The Commodore wasn’t very interested in building railroads. He preferred to buy ones that already existed and form a monopoly. His first major purchase was the New York and Harlem Railroad. At the time, it wasn’t considered particularly valuable as it only ran trains for part of the journey before connecting to horse-drawn carriages. However, it had prime position as the only railway that entered downtown Manhattan. Vanderbilt brought in his son, William, as vice-president of the Harlem line and, together, they soon made it profitable.

Next up, he took control of the Hudson River Railroad in 1864 and the New York Central Railroad in 1867. He also bought smaller, adjacent lines to consolidate them all into one giant railroad empire.

Vanderbilt was already 70 years old when he decided to get into railroads. He took a backseat role and mostly delegated orders to William and other subordinates, although he did enjoy taking inspection trips to oversee his domains. It seemed that his ruthlessness had subsided somewhat with age. Very rarely were there any cutthroat tactics to get his way. More often than not, Vanderbilt preferred simply to buy enough stock in a railroad until he became the majority shareholder and then appointed himself president. He even dabbled in philanthropy, donating $1 million to establish the Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

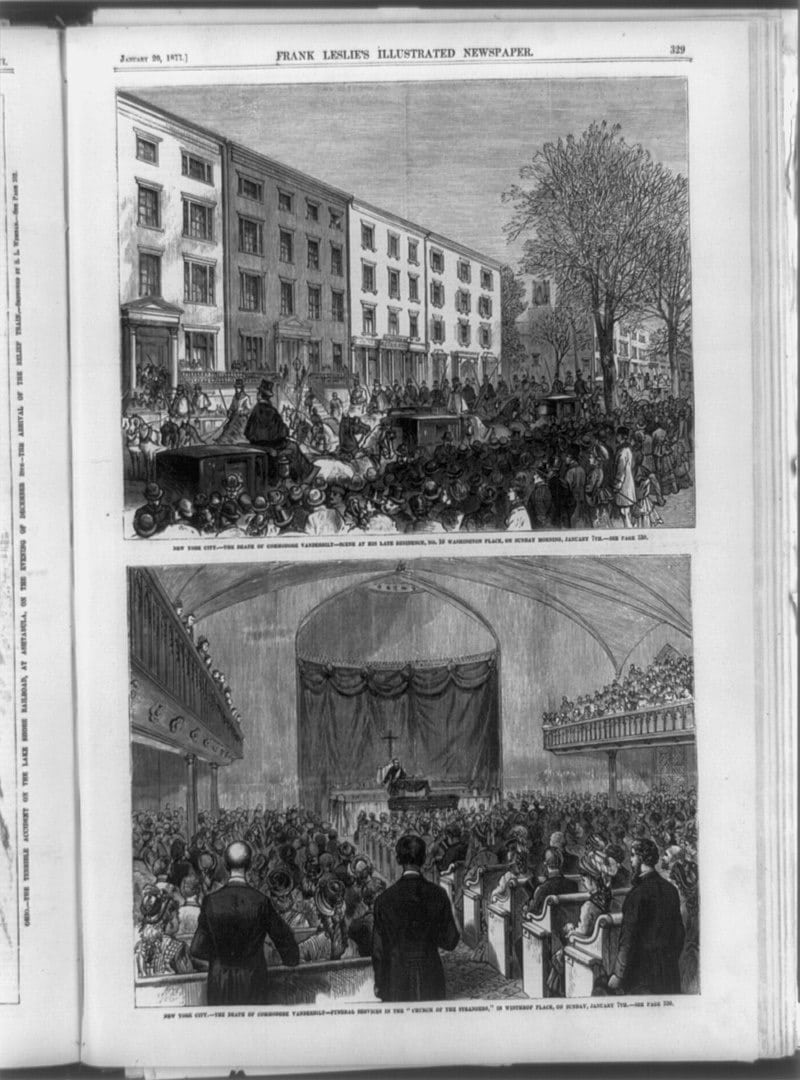

The last major addition to the Vanderbilt empire occurred in 1876 when the tycoon acquired the Canada Southern Railway. Soon after that, the 82-year-old Commodore fell gravely ill. His death was slow and painful, being bedridden for months before passing away on January 4, 1877. He remained a cantankerous, grumpy malcontent until the very end. On his better days, he would curse out his physicians and throw water bottles at them. On one occasion, he had to be physically restrained after trying to attack the media men who were keeping watch outside of his house to report on his death.

Vanderbilt’s death was followed by a long and messy lawsuit over his assets. Not wanting to split up his fortune, he left around $90 million of his $105 million estate to his son, William, while Frank and the rest of his children received much smaller amounts in cash or stock. And, in case you were wondering, that fortune means well over $200 billion in modern currency.