When it comes to being a Roman emperor, if you want to be remembered, there seem to be two surefire ways of doing it. One is to be a capable ruler and a strong military leader. Men like Augustus, Trajan, and Vespasian come to mind. The other is to go completely mad with power, like Caligula and Nero. For better or worse, history does seem to love a bloodthirsty, deranged lunatic.

Marcus Aurelius, an emperor who we’ve already covered, was firmly placed in the first camp. Therefore, it wasn’t unusual to expect his son, Commodus, to follow in his footsteps.

But he didn’t. No, in fact, Commodus was about as far removed from his father’s legacy as one would think possible.

Rise to the Throne

Commodus was born on August 31, 161 AD, in Lanuvium, the modern city of Lanuvio, about 20 miles southeast of Rome. He was the son of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius and his wife, Faustina the Younger.

Commodus was “born in the purple,” meaning that he was born during the reign of his father. He was the 17th Roman emperor, but the first to be born under these conditions. As Commodus himself said in a speech: “I never knew the touch of common cloth. The purple received me as I came forth into the world, and the sun shone down on me, man and emperor, at the same moment.” You might think this set him up for great things, but historian Cassius Dio described Commodus as being “as guileless as any man that ever lived,” characterizing him by cowardice, ignorance, and “great simplicity.”

In 166, the 5-year-old Commodus was named caesar by his father, which, by that point, was a dynastic title meant to designate him as the heir to the throne. Marcus Aurelius also appointed another one of his sons, Annius Verus, as caesar, showing that he intended for the two brothers to rule jointly, as he did with his own sibling, Lucius Verus. However, Annius Verus died in 169 AD and, for whatever reason, his father decided against appointing another caesar and kept Commodus as sole heir. In doing so, he broke with the tradition established by the past five Roman rulers, or the Five Good Emperors, as they were known, where each one selected his successor and adopted him.

Instead, Marcus Aurelius hoped that he could mold his own flesh & blood into becoming a great ruler. He provided Commodus with the best education that money could buy, paying large fees for scholars to come live in Rome and tutor his son. He took Commodus alongside him during military campaigns, even when he was young, so that he may learn how to command an army.

In 177 AD, Marcus Aurelius granted the title of Augustus to Commodus, thus equalling his own status and making his son co-ruler. Even so, he realized that the new emperor was still impatient and immature. In the last years of his life, Marcus Aurelius appointed many of his most trusted generals and companions to serve as advisers to Commodus. Then, in 180 AD, while engaged in the Marcomannic Wars, he died, leaving his son as the new sole emperor of Rome.

The First Plot

Commodus was 18 years old when he took over the throne in the middle of a war. He could have been a good ruler, if he would have been inclined to listen to the many guardians that his father had provided for him. Instead, it did not take long for him to start ignoring them completely to pursue his own whims or, even worse, the ideas of his sycophantic entourage.

It was these people that Cassius Dio blamed for the initial corruption of Commodus. He called the young emperor “the slave of his companions” and Greek historian Herodian agreed that these courtiers took advantage of the naive ruler and filled his head with tales of pleasures and delights awaiting him back in Rome. Commodus soon made his mind up – he wanted the war to end. Not because of the bloodshed or because it was best for Rome, but because he wanted to return to his palace and start living the lavish life of an emperor.

At this point in the war, Rome had the clear advantage. By pressing on, they could have neutralized enemies who had been causing problems for 15 years. Against the advice of all his generals, Commodus told them to negotiate peace as soon as possible. And so, the Marcomannic Wars ended in 180, with terms favorable to Rome, of course, but still mild compared to what they could have been.

Back in the capital of the empire, Commodus threw a celebration in his honor called a triumph, with games and music and feasts and handouts to the Roman populace to win over the people. In fact, Commodus managed to retain his popularity with the common man throughout most of his 12-year solo reign, mainly because he was often willing to open the royal coffers and spend money on lavish spectacles. Even so, it did not take long before those around him started to plot against the emperor.

In 182 AD, Commodus earned the ire of his older sister Lucilla, who was married to Claudius Pompeianus, one of the most distinguished generals under Marcus Aurelius who now mostly served as an ignored adviser to the new emperor. Before this, Lucilla had also been married to Lucius Verus, Marcus Aurelius’s brother and co-emperor. Therefore, Lucilla had been granted the title of Augusta and all the imperial honors that came with it. When Commodus became emperor, though, he married Bruttia Crispina and, all of a sudden, all the privileges of being Rome’s highest-ranking woman were afforded to her and Lucilla considered this a great insult. She knew that her husband, Pompeianus, would not take part in a plot to assassinate Commodus so, instead, she turned to a young nobleman named Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus, who was also rumored to be her lover.

Quadratus enlisted the help of a senator named Quintianus who agreed to attack the emperor in the entrance of an amphitheater under the shroud of darkness. According to historian Herodian, Quintianus had the opportunity to slay Commodus, but made the mistake of delivering a little speech beforehand, telling him that the Senate wanted him dead. The time he wasted was enough for the emperor’s bodyguards to pounce on him and kill the would-be assassin, thus foiling the first plot on Commodus’s life.

Afterwards came an investigation and everyone suspected of taking part in the plot was put to death. This included Quadratus and even the emperor’s sister, Lucilla, but curiously enough, Pompeianus was spared. Maybe Commodus genuinely believed that the general played no part in the matter, or maybe he still felt some kind of deference for one of his father’s closest allies. Either way, Claudius Pompeianus was allowed to quietly retire from Rome and go live on an estate in the country, citing his old age as an excuse.

Cassius Dio gave an interesting account of a man named Sextus Quinctilius Condianus who managed to fake his death and evade the wrath of Commodus. His family had been implicated in the assassination plot and his father and uncle had already been executed. When he heard that he, too, had been condemned to death, Condianus took a hare, killed it and drank its blood, but kept it in his mouth instead of swallowing. He then rode his horse and fell on purpose, vomiting up the blood. Those around him thought that he had been gravely injured and took him to his bed, believing he was at death’s door. Nobody questioned when news spread that Condianus had died, but he had already disappeared by that time, instructing his servants to place a ram’s body in his coffin and burn it. Commodus eventually learned of the deception and scoured the empire looking for Condianus, but he was allegedly never found and his ultimate fate remains a mystery.

Perennis and Cleander

The attempt on his life had a major impact on Commodus’s behavior. He took the words of Quintianus to heart and, from then on, considered the Senate his enemy. Throughout his whole reign, Commodus looked for new ways of curtailing the power of senators and other wealthy officials, including having them executed and their properties confiscated. After all, the money he spent on his lavish lifestyle had to come from somewhere.

Whenever a power vacuum is created, someone new always steps up to try and fill that void. As the Senators lost their authority and influence, other people from Commodus’s inner circle rose up to improve their station. One of those men was Tigidius Perennis, who was elevated to the position of praetorian prefect at the beginning of Commodus’s reign and steadily gained more power. For a time, he was considered the de facto ruler of Rome. He was more than happy to let the emperor engage in his licentious whims and games while Perennis took on more administrative duties.

He also turned the emperor against anyone he perceived to be a threat to his authority by convincing Commodus that they were plotting against him. That is how he got rid of the other praetorian prefect, Publius Tarrutenius Paternus, by implicating him in the plot to assassinate the emperor. Also, according to Herodian, Perennis targeted the wealthiest senators and, by confiscating their properties, made himself “the richest man of his time.”

Unsurprisingly, Perennis earned himself a lot of enemies, some because of his actions and others who were simply envious of his privileged position. But, as it turned out, he could not convince Commodus to have them all executed as there were other people, apart from him, who were in the emperor’s good graces. One of them was Marcus Aurelius Cleander, a freedman born in Phrygia, a region which is part of Turkey today.

Cleander had also risen up through the ranks by being a part of Commodus’s inner circle. Cassius Dio said that he possessed “the greatest influence after Perennis,” which is perhaps more impressive seeing as how Cleander had originally been brought to Rome as a slave to serve as a pack-carrier. However, by 182 AD, he was working inside the imperial household. After the assassination plot, Cleander killed Commodus’s chamberlain, Saoterus, who, allegedly, was part of the conspiracy, and assumed his position, thus entering into the emperor’s close confidence.

The Second Plot

Because Perennis and Cleander were both vying for the same position, that of the emperor’s must trusted sidekick, they hated each other and were always looking for ways to get rid of one another. In the end, it was Cleander who triumphed, if only for a little while.

In 185 AD, a curious scene unfolded during the Capitoline Games celebrating Jupiter. As the crowd filled the theater and Commodus took his seat on the imperial chair, an old man, apparently dressed like a philosopher, ran out into the center of the stage. He said to the emperor that “the sword of Perennis [was] at [his] throat.” He warned that the praetorian prefect was raising an army to oppose Commodus, who was sure to face death if he did not deal with the threat immediately. For his efforts, the old man was seized on the orders of Perennis and burned to death.

Commodus did not know how to react. It was true that Perennis had convinced the emperor to place one of his sons in charge of the army at Illyricum, a Roman province, but his suspicions were not raised enough to act against his confidant. Not yet, at least, but another event occurred a short while later which persuaded Commodus that Perennis had ambitions of overthrowing him.

A group of soldiers arrived in Rome and, without Perennis’s knowledge, went straight to the emperor. They had come from the prefect’s son in Illyricum where they had discovered that he had begun minting coins with the prefect’s portrait on it, in anticipation of Perennis claiming the throne. This was enough proof for Commodus who had Perennis arrested and beheaded, later having his son killed, as well.

It is unclear whether or not this plot was actually real and Perennis was, indeed, planning a coup, or if it was all a ruse to get rid of him, perhaps engineered by his most bitter enemy, Cleander. Herodian makes no claim or suggestion that Perennis had been the victim of a conspiracy, but Cassius Dio portrays the prefect in a positive light, saying that he “lived a most incorruptible and temperate life” and that he guarded “Commodus and the imperial office.” He also mentions that whenever something bad against Perennis occurred, Cleander was there to whisper in the emperor’s ear and, ultimately, it was he who convinced Commodus to deal with the prefect permanently. After the death of Perennis, Cleander was the most powerful man in the empire (after Commodus, of course) and he “refrained from no form of mischief, selling all privileges, and indulging in wantonness and debauchery.”

The Third Plot & Fall of Cleander

The next attempted plot against Commodus actually came soon after this one, in 187 AD, but it was only mentioned by Herodian so we aren’t sure how accurate it is. It concerns a soldier named Maternus, who deserted his legion and assembled a mob of outlaws to pillage towns and villages throughout the empire. It was a situation similar to that of Spartacus, where Maternus freed slaves and his ever-increasing army became strong enough to attack and plunder cities.

Eventually, the mob entered Italy itself and Maternus set his sights on the grandest prize possible – the throne of Rome. However, despite his army growing to a size he would have never expected, Maternus realized that it still wasn’t capable of standing toe-to-toe against the Praetorian Guard. Therefore, he reasoned that a cunning assassination plot would be preferable to an all-out battle.

Maternus picked the perfect time for it. It was the beginning of spring and the Romans were celebrating a festival honoring the goddess Cybele. Of course, it was a grand spectacle because, if there was one thing that Commodus was good at, it was throwing a party. During the revelry, it was customary for people to dress up and, on this occasion, no official or religious uniform was off-limits. Anyone could dress up as anyone else, so Maternus and his men donned the uniform of the Praetorian Guard, hoping that it would get them close to the emperor.

On paper, this sounded like a good plan, but it ended in failure as Maternus was betrayed by some of his men. He was captured and executed, while Commodus escaped yet another attempt on his life.

By this point, Commodus couldn’t help but notice that, despite all his executions, there were always new people appearing who wanted him dead. He was never the most attentive emperor in the world, but these plots persuaded him to spend less and less time in public. He was out of Rome, most of the time, preferring the remoteness and security of his private estates. This left the empire in charge of others, mainly Cleander.

Like Perennis before him, Cleander used his position to make himself the richest man in Rome. He sold governorships, military commands, senatorships, and even appointed 25 consuls in a single year, something which had never been done before. He was careful to send a large part of the money he made to Commodus, so that the emperor would not feel slighted or ignored. But, of course, nothing lasts forever and Cleander, too, had to fall.

This happened in 190 AD. In the previous year, Rome had been hit first by a plague, then a famine. The people were angry and they blamed Cleander as he became rather notorious for his greed. There was also the rumor, true or not, that the official had hoarded large supplies of grain because he thought this was the way to control the masses. This had the opposite effect, though, and riots broke out as violent mobs demanded his death.

Cleander tried to put an end to this. He sent out the imperial cavalry to chase down the rioters and gave the order to slaughter them all without mercy. But even this didn’t work as people barricaded their houses, climbed on their roofs and started pelting the riders with rocks and other projectiles. Eventually, word of the riot and the bloodshed reached Commodus who lived blissfully ignorant of the problems of the Romans. Cleander made sure of that, after all, but this time there was nothing he could do to save himself. Fearing that a civil war was ready to break out, the emperor had Cleander seized and beheaded, placed his head on a spear and sent it into the cheering crowd. Afterwards, Cleander’s sons were killed, as were all his close associates, and their bodies were, again, turned over to the ravenous mob, so that they could desecrate and mutilate them to their hearts’ content and satiate their bloodlust.

As the situation quieted down, Commodus realized that, once again, he had evaded peril. He was angry once he understood just how much power Cleander had managed to attain so he concluded that it was time for another series of executions and assassinations of the prominent men of Rome who could have posed a threat to him.

Commodus Enters the Arena

You might have noticed by this point that we haven’t spent a lot of time talking about the things Commodus did as emperor. That’s mainly because, despite a lengthy 12-year reign, there isn’t much to talk about. A war did break out in Dacia and a revolt in Britain, but these were both solved relatively quickly. Plus, it’s not like Commodus played any part in them. It was his generals like Pertinax, Clodius Albinus, and Pescennius Niger who acted, and all three of them would go on to have short reigns as emperor in the near future.

For the majority of his reign, Commodus stayed completely detached from all administrative concerns. He was too busy playing games and having feasts to bother himself with trivial matters such as running an empire. It wasn’t until the last few years, after the death of Cleander, that Commodus became more involved, and that is when he truly indulged in his egomania and madness.

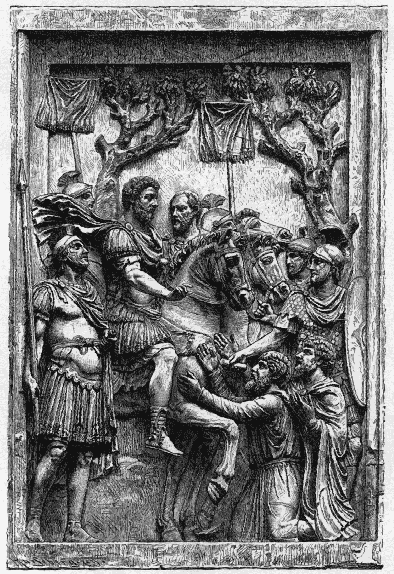

For starters, he decided that he was the reincarnation of Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. Therefore, this allowed him to “found” the city again, and rename it Commodiana, while the people were now no longer Romans, but Commodians. Not satisfied, Commodus also concluded that he was the reincarnation of Hercules and had statues erected of him where he was depicted dressed like the mythological hero, swinging a club and wearing the pelt of the Nemean lion.

He took on a few more names and titles, as evidenced by the official greeting to the Senate: “The Emperor Caesar Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus Augustus Pius Felix Sarmaticus Germanicus Maximus Britannicus, Pacifier of the Whole Earth, Invincible, the Roman Hercules, Pontifex Maximus, Holder of the Tribunician Authority for the eighteenth time, Imperator for the eighth time, Consul for the seventh time, Father of his Country, to consuls, praetors, tribunes, and the fortunate Commodian senate, Greetings.” All of the names we just mentioned above – Commodus also used them to rename the months of the year in his honor.

Because he saw himself as Hercules, Commodus did something no other emperor had done before – he became a gladiator, actually taking part in fights inside amphitheaters. Well, he was more of a bestiarius, if we’re being technical, as he generally preferred to fight animals, not humans. And when we say fight, we mean in an obviously rigged situation that posed no threat to him whatsoever. When he went against animals, Commodus usually hunted them from an elevated platform where they couldn’t reach him. Only if the animals were harmless would Commodus have actually entered the arena floor. To give him his due, it appears that Commodus was a skilled marksman, and could easily bring down animals from afar with arrows and javelins.

If the emperor was fighting other people, they obviously knew not to harm him. Not that they would have been able to, even if they wanted, as they were armed with objects such as wands and sponges. And for each performance, Commodus paid himself one million sesterces (somewhere around $2 million), which also made him the highest-paid gladiator of all time.

Cassius Dio who, as a Senator of Rome during the time of Commodus, was front and center for all of this, by the way, mentions one episode where the emperor beheaded an ostrich. He then approached the Senators and pointed his bloody sword at them, then at the ostrich head, suggesting that that would be them one day. According to Dio, he and the other senators got in the habit of secretly chewing laurel leaves while attending these spectacles so as to not burst out laughing in front of the emperor. All of them had to attend these events, and all of them did except Claudius Pompeianus who said that he would have preferred death over seeing the son of Marcus Aurelius in this position.

The Fourth & Final Plot

Commodus had escaped quite a few plots against him during his reign, but it was inevitable that, eventually, his time would run out. This happened on New Year’s Eve, 192 AD. During the celebrations, Commodus wanted to make an appearance not from the imperial palace, as was tradition, but from the gladiatorial barracks, wearing armor and surrounded by the other gladiators. He shared his plan with Marcia, his favorite mistress, who then started crying and begging Commodus not to disgrace himself in such a way. He also told Eclectus, a trusted servant, and Aemilius Laetus, the praetorian prefect, but they reacted in similar ways. None of this changed his mind, of course, but the emperor did decide to have the three executed for their insolence, and secretly wrote down their names on a list of people to be killed at the start of the New Year.

As it happened, Marcia came into possession of this list and shared her findings with Laetus and Eclectus. They had little choice – it was either them or Commodus and, unsurprisingly, they chose the latter.

Later that day, as the emperor was taking a bath, Marcia brought him a cup of wine which had been poisoned. Commodus drank the whole thing, but it caused him to be violently ill, vomiting the lethal liquid before it had time to do its job. It was now far too late to back away, so the conspirators bribed a young, strong wrestler named Narcissus to enter the bathroom and strangle the emperor.

And so he did, and this was not only the end of Commodus, but also that of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. His death was followed by one of the most turbulent periods in Roman history known as the Year of the Five Emperors. But we’ll talk about that another time.