If there’s one thing Americans love, it’s an underdog story. And the story of a son of immigrant parents, raised in the rural backwoods of America, orphaned as a teenager, who not only rose to the heights of respectability, but to the very pinnacle of American politics, the Presidency? That is one of the all-time underdog stories. For Andrew Jackson, this wasn’t merely a story, however: this was the remarkable story of his own life.

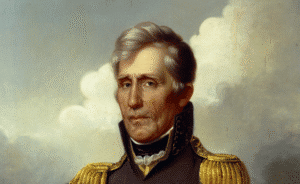

For many years, Andrew Jackson was considered among the very greatest of American presidents. He helped to define the office itself in its modern sense: beginning the transition of the job from that of an administrator, obeying the dictates of Congress, to the center of American political life that it is today. He was seen as a man of the people, a war hero who had defended the nation from the wrath of the Indians and the British, who now sought to defend it from the corrupt government institutions and wicked financial interests that profited at the expense of the common man. He was brave, he was bold, and he was decisive: all the things the ideal American man should be.

But underneath this polished veneer was an undisputable dark side, a dark side that made Jackson a polarizing figure even within his own lifetime. He had a truly volcanic temper, a temper that manifested itself in his younger days with sudden outbursts of violence and in later years with a steely determination to destroy his opponents, whatever the cost. But it isn’t the despicable things that he did when he lost his temper that have caused a relatively recent (largely negative) historical reevaluation of America’s seventh President: it is the despicable things he did with a clear mind and even clearer conscience.

Jackson’s personal fortune was built on the backs of enslaved human beings, buying and selling and treating them like livestock, as many as 150 at a time. And he was the driving force behind one of the worst things the American government has ever done: the forcible removal of American Indian tribes from their ancestral lands to new reservations west of the Mississippi River, resulting in thousands of deaths on the “Trail of Tears.” This was not only condoned by the American people at the time, but celebrated as one of Jackson’s landmark achievements, enriching thousands of white settlers at the Indians’ expense.

Andrew Jackson’s story is a complicated one to tell, full of triumphs and personal tragedies, heroic moments and shameful ones in almost equal measure. Overall, it is the story of a man determined to overcome his unfortunate circumstances and make his mark on the world. And, for better or worse, he did.

The Angry Young Rebel

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, the son of Irish immigrants who had moved to the Waxhaws region of the Colonial Carolina Territory 2 years earlier (no one is exactly sure whether he was born in North or South Carolina, since the border in that area was largely undefined). Jackson never knew his father, also named Andrew: he had died three weeks before he was born, leaving his mother, Elizabeth, alone to raise him and his two older brothers in one of the most remote regions of colonial America.

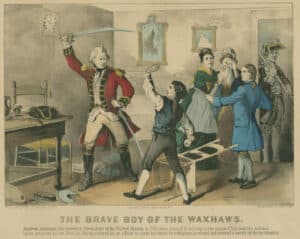

The American Revolution would bring further tragedy to young Andrew: both his brothers died fighting for the Patriot cause, and Andrew himself was taken prisoner by the British at the tender age of 14, fighting as a Patriot partisan. Soon after being captured, an officer ordered Jackson to polish his boots. When the boy refused, claiming to be a prisoner of war, the officer slashed him with his sword, cutting open his left hand and the top of his head, leaving scars he carried for the rest of his life.

Jackson very nearly died in captivity, and soon after his mother had nursed him back to health after securing his release, she died of cholera while tending to sick relatives. The teenager was now an orphan, passed around from relative to relative when they tired of the boy’s explosive temper and brash nature. It seemed like Andrew Jackson was destined for a life of poor prospects.

But Jackson was determined to make something of himself. He was not, as his detractors later suggested, an illiterate country bumpkin: his mother made sure her son received as good an education as possible, considering his remote upbringing, eventually hoping he would pursue a career in the ministry. Instead, Jackson studied the law, being admitted to the North Carolina bar in 1787, and the next year moved to the town of Nashville in what was then the far western part of the state.

The Charming Rake

Andrew Jackson, obviously, was not born into money. If he wanted to earn a place among the higher echelons of society, he would need to use what he had: his brains and his ability to charm people. Being a backwoods lawyer didn’t pay particularly well, so to supplement his income, he dabbled in land speculation and was also a “prolific” slave trader, regularly shipping consignments of enslaved black men and women downriver to Natchez, Mississippi, and New Orleans, Louisiana, where they were constantly in demand.

As much money as Jackson made, however, he spent it just as quickly: on fine clothes, exotic wines, on bad land deals, but his biggest money sink was gambling. Jackson wagered (and lost) large amounts of money on horse races, card games, and cock fights. All these activities, which caused him to be known about town as a “charming rake,” also helped to ingratiate him within the planter class of Nashville society, which also gave him inside access to the region’s political powers.

When the Southwestern Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Tennessee in 1796, Jackson was elected to be the state’s first Congressman. He arrived in Philadelphia in time to see the end of George Washington’s political career, and in a sign of things to come, was one of the few members of the House who refused to applaud the nation’s first president when he gave his farewell address because of his fury over the signing of the Jay Treaty with Great Britain (Jackson would carry a fervent hatred for the British all his life, no doubt a result of his childhood experiences during the Revolution.) He was then elected to the US Senate, but lasted in that job only six months before he resigned and returned to Tennessee, where he was appointed a judge in the state’s Superior Court.

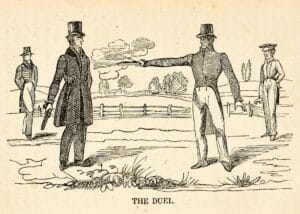

While Jackson could be charming when he wanted to, when he lost his temper (something that happened frequently in his younger years), he often made the impulsive decision to resolve quarrels with violence. He was involved in a dispute with the former governor of Tennessee, John Sevier, that ended in a shootout on the streets of Nashville in 1802 (no one was hurt). In 1806, a quarrel over a gambling debt with a man named Charles Dickinson ended in a formal duel: Dickinson shot Jackson in the chest, but remarkably, the lead ball smashed into his sternum and broke apart, saving his life. Bleeding profusely, Jackson remained on his feet and calmly fired his own pistol, killing Dickinson instantly.

In another fight in 1807, Jackson stabbed a man in the back with a sword cane, for which he was brought up on charges of assault and attempted murder (he was acquitted of the charge). Finally, there was the infamous “fracas” in a Nashville tavern in 1813 between Jackson and the Benton brothers: Thomas, a future US Senator, and Jesse. It was a particularly ugly brawl, involving knives and whips, and then the guns came out: Jesse shot Jackson in the shoulder, a serious injury which nearly killed him and left him in a sling for months.

Unlikely War Hero

In 1802, Jackson was elected to command Tennessee’s state militia, despite possessing little military experience and no formal military education. However, Jackson was a natural-born leader, the kind of man people gravitate around, particularly in a crisis, so it wasn’t surprising he took to command very well. That would be put to the test during the War of 1812, which again saw the Americans facing off against the British.

However, Jackson’s first taste of formal combat would not come against Great Britain, but against a faction of Creek Indians known as “Red Sticks,” who had heeded the call of Shawnee chief Tecumseh for a general Indian uprising against the Americans, who routinely encroached on their land and murdered tribal members. Jackson led a successful campaign against the Red Sticks, culminating in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend deep within the future state of Alabama, in which over 800 Red Sticks were killed (Jackson’s force lost 70 men). Jackson forced the Creeks to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, ceding 23 million acres of land to the United States, including land occupied by Creeks that had been allied to the US during the war.

Jackson then turned his attention to the British, who were preparing to attack the city of New Orleans. It was an important strategic position: near where the Mississippi River emptied into the Gulf of Mexico, and could not be lost. Jackson, now a major general in the US Army, was ordered to protect it. Jackson arrived in December 1814 and put the city under martial law. He scrambled to find any troops he could get his hands on to oppose the British: freed slaves, Native Americans, French Creoles, Spanish-speaking men from Mexico and Florida, even pirates from Barataria Bay, led by their enigmatic commander, Jean Lafitte (Author’s Note: Pronounced La-Feet). Altogether, Jackson had a force of some 5,000 men to face off against the 10,000 British soldiers under General Sir Edward Pakenham, who, like most of his men, was a seasoned veteran of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe.

Jackson made his stand five miles southeast of the French Quarter, in the modern-day suburb of Chalmette. He turned the old Rodriguez Canal into “Line Jackson,” a formidable earthwork that blocked the narrow avenue of approach to the city between the river and an impassable swamp. The British arrogantly believed that their army was superior to the scratch force put up by the Americans, and on January 8th, 1815, launched a full frontal assault on Jackson’s line.

The Battle of New Orleans was a complete disaster for the British. The redcoats marched right up to the American earthworks and were repulsed by heavy fire, including from heavy naval cannons taken off of ships and manned by Lafitte’s pirates. In roughly 30 minutes, the British suffered over 2,000 casualties, 25% of their attacking force, while the Americans, protected by their fortifications, only lost 13 men killed and 39 wounded. The dead included General Pakenham and his 2nd in command, General Gibbs.

Old Hickory

The ironic part about the Battle of New Orleans was that it took place after the War of 1812 was already over: the Treaty of Ghent had been signed by the warring parties two weeks before the battle, but word would not make it across the Atlantic until February 1815. Though it did not affect the outcome of the war, the battle did leave a lasting impact in that it made Andrew Jackson a national hero. In the aftermath of one of the most lopsided victories in American history, everyone was singing the praises of “Old Hickory,” the nickname his soldiers had given him because of his unbending toughness.

Jackson remained in the army until 1821, when budget cuts reduced the size of the armed forces and eliminated his position. After a brief period as the territorial governor of Florida, Jackson returned to the Hermitage, his sprawling 1,000-acre cotton plantation outside of Nashville he’d purchased in 1804. It was one of the largest estates in Tennessee and made Jackson one of the wealthiest men in the state. But he wasn’t to remain there for long: his military fame made him the perfect candidate in the eyes of many for national political office. Namely, the Presidency of the United States.

Originally seen as a long-shot candidate in the 1824 election, Jackson proved to be surprisingly popular and ended up getting more votes than the other three candidates both in the popular vote and in the Electoral College. However, for only the second time in history, no candidate received an outright majority of electoral votes, throwing the election to the House of Representatives. Jackson was furious when he lost the House vote to John Quincy Adams, alleging that there had been a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Speaker of the House Henry Clay, that Clay had engineered Adams’ election in return for being named Secretary of State. Historians find this unlikely, since Clay was outspoken in his view that a Jacksonian Presidency would be a disaster for the country: the two would remain bitter enemies for the rest of their lives.

Jackson returned to Tennessee and almost immediately began preparations to try again in 1828. In what has been described as the “first modern Presidential campaign,” Jackson built a national coalition of supporters, including Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (who became his running mate), and Senator Martin Van Buren of New York. Jackson also benefited from steps taken to increase suffrage to all (white) male voters, rescinding most of the property owning and tax paying requirements that had been on the books previously. Jackson ran on a campaign of representing the common people of the country; his supporters called their political party “the Democracy,” the nucleus of which would go on to form the modern-day Democratic Party. Their enemy was what they called the “entrenched elites” of Washington, who looked down their nose at the common man while they ran the country among themselves.

A New Kind of President

The 1828 campaign was particularly vicious, with both sides firing personal attacks at each other. What was most unforgivable in Jackson’s mind, however, were the attacks made against his wife, Rachel. The point of contention was that, at the time Jackson married Rachel, she was still technically married to another man, despite the fact that the marriage was unhappy and the couple no longer lived together. What had been seen as simply a matter of slow paperwork was blown up by Jackson’s opponents into charges of adultery, which at the time was not only considered societal suicide, but was, in many places, a crime.

Jackson won the election in a landslide in 1828, handily defeating Adams, but Jackson never forgave the men he called his “slanderers,” particularly since he was going to Washington DC without his wife: she had died in December 1828, and Jackson blamed the stress caused by the campaign rhetoric for her death.

From the beginning of his time in office, Jackson was determined to be a different kind of President than those who had preceded him. He started by remaking the Executive Branch: firing thousands of federal appointees and replacing them with Jackson loyalists. He argued that it was a President’s privilege to do this, since he had won the election, and as the saying goes, “to the victor go the spoils.” The so-called “spoils” system of political patronage would endure for decades, and eventually become so corrupt that the modern civil service system was devised to replace it.

Like many in the planter class, Jackson hated banks, particularly the Second Bank of the United States, which he believed favored Northern manufacturing interests ahead of Southern agricultural ones. He made it his personal mission to destroy the national bank, vetoing a congressional bill to recharter it and then ordering his Treasury secretary to pull all federal deposits out of it, fatally crippling it. His veto pen usage was another novel way he was remaking the Presidency: in the past, Presidents had used the veto sparingly, even signing bills they personally disagreed with because it was the will of Congress. But Jackson, who believed he had a mandate from “the people,” used it to kill bills he was politically opposed to, vetoing more legislation during his presidency during his time in office than all six of his predecessors combined. Slowly but surely, Jackson was remaking the office of the President, turning it into the center of American political life, where it still remains today.

King Andrew the First

Much of Jackson’s time in office was spent resolving crises and controversies. There was the “Petticoat Affair,” in which his Cabinet was fatally split because most of Washington society refused to socialize with Secretary of War John Eaton, whose wife, Margaret, was demonized as a “harlot.” The discord became so bad that Jackson asked his entire Cabinet to resign in 1831, rather than admit he’d been wrong to defend his friend Eaton.

Then there was the “nullification crisis,” a standoff between the federal government and the state of South Carolina over the issue of protective federal tariffs. South Carolina pushed the theory of “nullification” forward: that if a state disagreed with a law passed by Congress, it could nullify it, making it not apply within state borders. Jackson, who believed that if South Carolina was permitted to defy the federal government, it would fatally weaken the Union to the point of breaking up, threatened to raise an army of 300,000 troops to enforce federal law in South Carolina. A potential civil war was averted when a compromise amending the tariff was passed in Congress, but Jackson correctly predicted that this particular issue was not over: South Carolina would be the first state to secede from the Union following the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Practically everything Jackson did was controversial, and he constantly had to fend off charges from his political foes that his moves to consolidate executive power were steps towards dictatorship. His detractors began derisively calling him “King Andrew the First,” and the political party that formed to oppose the Jacksonian Democrats was called “the Whigs” because that was the party in Great Britain that opposed the interests of the monarchy. Jackson was so controversial that it isn’t surprising that he was the first President to face an assassination attempt: a man named Richard Lawrence aimed two pistols at Jackson as he was leaving the Capitol Building in January 1835. Fortunately for Jackson, both pistols misfired, and the President retaliated by beating the man with his cane until the two men were separated (Lawrence was later judged to be insane and confined to a mental institution). Jackson also became the first President to be censured by Congress over his move to remove the government deposits from the national bank (the censure was later rescinded by a more friendly Congress just before Jackson left office).

However, Jackson remained popular with the voting public at large: he was overwhelmingly re-elected to a second term in 1832, and many of his initiatives were popular. This included his support for the Indian Removal Act, which forced all American Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River to move to new lands in the as-yet unsettled West: thousands died of disease and malnutrition on the “Trail of Tears,” and modern scholars have referred to the act as genocide. However, there was little opposition to the removal among Americans at the time, and many in the South celebrated the opportunity to get at the former Indian territories for themselves. In 1835, Jackson paid off the national debt, the only time in American history this has been done, and during his term, added two new states to the Union: Arkansas and Michigan. Jackson was also popular in the South for his defense of the institution of slavery: he ordered the Post Office not to deliver abolitionist mailings in slaveholding states, which violated the First Amendment, and believed it was those who sought to abolish slavery that were threatening to destroy the Union, not the slaveholders (his views were no doubt influenced by his long time status as a slaveholder himself: he certainly viewed slaves as little better than livestock based on his writings on the subject.)

Tainted Legacy

By the time Jackson left Washington in 1837, the entire American political landscape had changed. Jackson’s presidency had created two new political parties that would fight it out on the national stage until the collapse of the Whig Party in the 1850s (it was soon replaced by the new Republican Party). Abraham Lincoln would use Jackson’s rhetoric in the nullification crisis as justification for preventing the Southern States from leaving the Union in 1861, and other strong-willed Presidents such as Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt would echo Jackson’s ethos that they, not Congress, not the judiciary, were the true voice of the people. The presidency itself has slowly amassed more and more executive power as time has gone on, so that the modern-day job little resembles what it was before Jackson came to the White House. In addition, every populist politician from William Jennings Bryan to George Wallace to Bernie Sanders has used similar rhetoric of the common man vs. “the elites,” though the definition of both has been constantly evolving since Jackson’s day.

These are all legacies of Andrew Jackson, who retired to the Hermitage and died in 1845, being buried next to his beloved wife in the back garden. There are statues of him in Washington DC, New Orleans, Nashville, and Jacksonville, Florida (which was named for him), and his portrait to this day is printed on the US Twenty Dollar bill, despite attempts to remove it (a rather ironic tribute to a man who hated paper money and believed only gold and silver should be valid US currency). However, Jackson is no longer the beloved icon he once was: historic re-evaluation of his life and career has cast his deeds into a new, darker light, particularly his violent actions to enforce and enhance white supremacy in America. The Trail of Tears is a particularly difficult stain to wash off his reputation.

However, for better or worse, Andrew Jackson rose from nothing to become one of the most influential men in American history. His legacy will likely live on for as long as the United States itself does, so profound was his impact. No doubt he’d be pleased by this, as a man obsessed with his legacy, though he’d probably be furious about some of the things said about him nowadays. Good thing duelling’s gone out of fashion.