“Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.”

Those are the opening lines of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous 1860 poem Paul Revere’s Ride, which immortalized in verse Revere’s pivotal contribution to America’s fight for independence during the Revolutionary War.

But just how pivotal was it, really? It’s not a stretch to say that, if it weren’t for the poem, you and I and most people alive today would have no idea who Paul Revere even was. He certainly would not be getting the Biographics treatment.

The truth is that poets rarely strive for historical accuracy and Longfellow was no different. His poem got a lot of the facts wrong, although it did accomplish its goal of turning Paul Revere into a folk hero and a household name. Before that, believe it or not, his midnight ride was a mere footnote in history. It was deemed so unimportant that it wasn’t even mentioned in Revere’s obituaries when he died. So today we will be looking at Paul Revere and his famous ride without the benefit of an artistic license.

Early Years

Paul Revere was born in Boston’s North End on January 1, 1735, occasionally listed as December 21, 1734, going by the Old Style calendar. He was the son of Apollos Rivoire, a French Huguenot who emigrated to America when he was a 13-year-old boy and became an apprentice to a skilled Bostonian silversmith named John Coney. At some point, he decided to Anglicize his name so “Apollos Rivoire” became “Paul Revere,” but we’re going to keep calling him Apollos so we don’t confuse him with his son. We don’t know when he fully completed his training, we just know that it happened by 1730 thanks to a newspaper advertisement in The Weekly News Letter announcing that “Paul Revere, Goldsmith” was moving his shop from the Town Dock to the North End. Also around that time, Apollos Rivoire met Deborah Hitchbourn. The two got married on June 19, 1729, and went on to have twelve children together, with Paul being the eldest son.

As a boy, Paul Revere received an education at the North Writing School, but only enough to get by. When he turned 13, Paul left school and became a silversmith apprentice just like his father, wanting to learn the family trade. This was fortuitous because Apollos passed away in 1754, leaving the 19-year-old Paul Revere in charge of the household and the family business.

Unfortunately, the law disagreed on that last point. For an artisan or tradesman to open a shop, he had to be over 21 years old and have served an apprenticeship for at least seven years. Paul failed on both counts, so he had to keep apprenticing for two more years with a different silversmith before he could take over the family business. Luckily, the law allowed Apollos Rivoire’s widow to continue his trade, even if it was just in name only. Paul had to do the actual work to provide for the family while simultaneously finishing his apprenticeship at a different silversmith and also teaching his younger brother Thomas the smithing trade.

It was a long two years for Paul Revere, but he pulled it off, and, in 1756, he gave himself some well-deserved rest by going off to fight the French.

In 1754, the French and Indian War erupted in North America, pitting British colonies against French ones, each side aided by various Native American factions. We’re not really sure why Revere decided to enlist. It seemed like he had his hands full at home, but maybe he thought the pay would be better. Or maybe he was simply bored of making belt buckles and spoons all day and night. Whatever his motivation might have been, Revere joined an artillery regiment with a commission as a second lieutenant and spent the summer of 1756 stationed at Fort William Henry by Lake George in New York.

This, however, turned out to be a completely fruitless endeavor. Ostensibly, the plan was for the regiment to wait for the opportune time to help capture Fort Saint-Frédéric from the French, but that time never came. Eventually, with food getting scarce and winter approaching, the unit was disbanded and Paul went home.

No Taxation Without Representation

Back in Boston, Revere officially took over the family silversmithing business, with his younger brother Thomas serving as his apprentice. In 1757, he also married his first wife, Sarah Orne. They were married for 16 years until she died in 1773. Revere remarried that same year to Rachel Walker, and he had 16 children in total (eight with each wife), although only five of them ended up outliving him.

Life in Boston wasn’t so profitable following the French and Indian War. The economy was in a recession, so Revere had to find additional sources of revenue. Although silversmithing remained his main trade throughout his adult life, he branched out into engraving, producing copperplate illustrations for magazines, books, bills, cartoons, and business cards. Revere also tried his hand at some basic dentistry for a while, manufacturing, cleaning, and repairing false teeth.

Contrary to a popular myth, Paul Revere did not make George Washington’s false teeth. He never made a full set of dentures in his life. It was something beyond his skill level, although we can credit Revere with an early example of dental forensics. Among Revere’s most prominent clients was the Founding Father Joseph Warren, one of Boston’s leading figures during the early days of the American Revolution. In fact, it was Warren who sent Revere out on his famous “midnight ride” on that fateful night in 1775. But later that same year, Joseph Waren was killed at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and buried in a mass grave for nine months. When he was finally dug up alongside the rest of the battle casualties, decomposition made identifying the bodies through traditional methods impossible. However, Paul Revere was able to recognize the remains of his friend thanks to a dental prosthesis made out of ivory and gold wire that he had fitted to Warren years earlier. This became the first instance in American history of using dental remains to identify a military service member.

Anyway, even with the dental and copper plating side gigs, Revere was still hurting for money. So were many others in the colonies, and the British Parliament was about to make it even harder when it passed the Stamp Act in 1765. According to this new act, printed materials produced in the colonies had to be made using special stamped paper from London that included a revenue stamp. This was a new tax that targeted everything from newspapers and magazines to legal documents and even playing cards and the goal was to raise more money to cover the costs of the British troops stationed in North America.

The reception to the act was poor, to put it mildly. Colonists considered the extra soldiers unnecessary as an attack from the French wasn’t imminent. But even if it were, the colonies argued that they had already paid enough during the war, so if anyone was footing the bill, it should be London, not them. But the biggest gripe of them all was that the British Parliament should not be allowed to tax the colonies without consent from the colonial legislature. “No taxation without representation” became the widely distributed slogan that summed up their feelings on the matter.

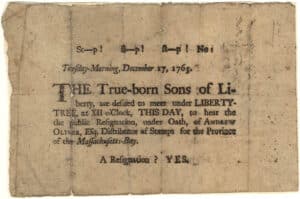

Protests against the Stamp Act erupted all over Colonial America. A group known as the Loyal Nine stirred up several angry mobs in Boston that hanged effigies, led processions through the city, and, on one occasion, raided and destroyed the home of the lieutenant governor. Inspired by their actions, another underground organization was formed with similar goals to fight taxation, but in a more cloak-and-dagger sort of way. They were known as the Sons of Liberty.

Credit for founding the Sons of Liberty usually goes to Samuel Adams, but in a short while, what started as a small-time operation grew into a resistance network with chapters throughout most of the colonies. The Sons of Liberty included many figures who would go on to play important roles during the American Revolution, including the aforementioned Joseph Warren, and, of course, Paul Revere.

Initially, it seemed as though the efforts of the protesters paid off. The Stamp Act was repealed after only one year but with one important caveat. The American Colonies Act 1766, also commonly referred to as the Declaratory Act, was approved at the same time as the repeal, and it stated unequivocally that the King and Parliament had the power to enact any legislation onto the colonies, so enough of all that “no taxation without representation” malarkey. This also made it likely that, even though the Stamp Act had been repealed, new taxes would be looming on the horizon. Indeed, between 1767 and 1768, Parliament passed a series of five new ordinances and duties affecting the colonies, collectively known as the Townshend Acts, so it seems like the Sons of Liberty still had a tough job ahead of them.

An Engraving & A Tea Party

At first, Revere used his skill as an engraver to aid the cause of the Sons of Liberty. He engraved and distributed political pamphlets and cartoons that roused people to act against the unchecked tyranny of the British Crown. His most famous engraving was, arguably, also his most controversial. It came following the Boston Massacre, a seminal event in the lead-up to the revolution when British soldiers opened fire on an angry crowd and killed five men. The Sons of Liberty heavily publicized the killings to garner support and Paul Revere’s depiction of the event was widely distributed throughout America. However, it seems that Revere modeled his illustration after a drawing from another engraver, Henry Pelham. Well, “modeled” would be the polite way of putting it. “Copied” is more accurate since the two images were almost identical, and “stolen” would be even more apt since Revere had asked to borrow Pelham’s work, didn’t give any credit to him, and put his version up for sale before the original came out. Unsurprisingly, Pelham wasn’t too thrilled about it and wrote Revere a scathing letter that said:

“Sir,

When I heard that you [were] cutting a plate of the late Murder, I thought it impossible as I knew you [were] not capable of doing it unless you copied it from mine and as I thought I had entrusted it in the hands of a person who had more regard to the dictates of Honour and Justice… But I find I was mistaken and after being at great Trouble and expense of making a design, paying for paper, printing & etc., find myself in the most ungenerous Manner deprived not only of any proposed Advantage but even of the expense I have been at as truly as if you had plundered me on the highway. If you are insensible of the Dishonour you have brought on yourself by this Act, the World will not be so. However, I leave you to reflect and consider one of the most dishonorable Actions you could well be guilty of.”

As you can see, Pelham was throwing some serious shade, but before everyone gets out the pitchforks, it seems that the two eventually hashed things out and, by 1774, even entered a business partnership together where Revere handled the engraving for Pelham’s drawings.

But engraving was just one of the ways that Revere furthered the cause of the revolution. He was also a courier for Boston’s Committee of Safety, traveling to Philadelphia and New York to deliver important news. He did this numerous times between 1773 and 1775 and his experience as a covert rider was part of the reason why he was chosen for the famous ride in the first place.

His most noteworthy ride (other than, you know, that one) took place in December 1773, after another iconic historical moment – the Boston Tea Party. Earlier that year, the British Parliament passed the Tea Act to help the struggling British East India Company unload its large surplus by allowing it to ship its tea directly to North America and sell it duty-free. Up until that point, the East India Company could only sell its tea in London where it paid duty on it and middlemen would bring it to the colonies. Consequently, the vast majority of the tea consumed in the colonies was smuggled Dutch tea.

Make no mistake about it, the new act would not have made British tea more expensive for the colonists. If anything, it actually became cheaper and was of higher quality than the smuggled one. So why were the Sons of Liberty and other Patriots against it? Because although the British East India Company wasn’t paying any duties on the tea, the colonists were still paying the Townshend tax on it. The price itself wasn’t the problem, but the validation of a tax that had been imposed on them by the British Crown. If the colonists went along with this tax, then surely others would follow. Plus, it undermined all colonial tea businesses, both those that smuggled Dutch tea and those that were legitimate middlemen for East India.

In late November, the Dartmouth arrived in Boston Harbor carrying hundreds of chests of tea. In other cities, the locals either persuaded the captains to return to England without paying the duties or forced the consignees to refuse the tea, usually under threat of being tarred and feathered. But neither strategy worked in Boston. Two of the consignees were sons of the governor, so they couldn’t be strongarmed, while the governor himself refused to allow the Dartmouth to leave. Eventually, after 20 days of sitting in the harbor, customs officials could confiscate the cargo, meaning that the governor would get the tea, regardless of whether the duties had been paid or not.

As the deadline approached, the Sons of Liberty decided to take drastic action, so on December 16, 1773, about 50 of them, Paul Revere included, disguised themselves as Mohawk warriors, boarded the Dartmouth and two other ships, and dumped their tea in the harbor. Afterward, as most Patriots went to rest after a job well done, there was one whose task was still unfinished – Paul Revere. The Committee of Correspondence wrote an account of what had happened and Revere rode to Philadelphia and New York to let them know what the lads in Boston had just done.

The Midnight Ride

The Boston Tea Party caused a huge outrage back in England and Parliament decided to punish the colonies with a series of disciplinary measures known as the Intolerable Acts. The first one, the Trade Act 1774, shut down the Port of Boston until restitution was made for the lost cargo. The second measure was the Massachusetts Government Act which repealed the colony’s charter and gave expansive powers to the governor who was loyal to the Crown.

Colonists considered the acts to be tyrannical and in violation of their constitutional rights. With each passing day, it was becoming more and more evident that a peaceful resolution was highly unlikely between England and its American dependencies.

1774 was a tense year. Militia units had formed all over the colonies, basically just waiting for the call to go to war. There were a few false alarms, one given by Paul Revere himself in December. He had received word that British redcoats were headed for Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to seize the gunpowder from Fort William and Mary. On the morning of December 13, Revere got on his horse and rode 66 miles to warn the locals. The next day, around 400 Patriots raided the fort to secure the powder for themselves, only to discover that Revere’s info was wrong. Still, since they had already captured the guards, might as well take the powder and the muskets while they were there. They were bound to come in handy sooner or later.

Just four months later, Paul Revere was called upon to ride again. On the evening of April 18, 1775, Joseph Warren tasked Revere with going to Lexington to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams that redcoats were coming to crack down on the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and to seize or destroy all the ammunition and gunpowder that the Patriots had stockpiled at Concord.

The first alert was given not by Paul Revere, but by Robert Newman, the sexton of Boston’s Old North Church. He lit two lanterns in the church tower to let others know that the British were traveling via the Charles River instead of marching through the Boston Neck. “One if by land, two if by sea” is the famous line that marks this occasion, but this is the first place where Longfellow’s poem gets the facts wrong. The lanterns weren’t meant to signal Revere, but other Sons of Liberty across the river in Charlestown in case Revere was prevented from leaving the city.

But Revere did make it out of Boston and into Charlestown. There, he discovered that he had a tough mission ahead of him as British patrols littered the area trying to prevent riders from doing exactly what he was doing. In fact, Revere was almost caught right after leaving Charlestown, so he changed his route and first traveled to Medford where he met up with militia captain Isaac Hall. At that point, Revere inquired if his friend William Dawes had also arrived, because one crucial detail that the poem leaves out is that William Dawes had set off on his very own midnight ride. Wisely, Warren chose not to put all his eggs in Revere’s basket, so he dispatched Dawes with the same mission, but through a different route.

Dawes had not arrived yet. He was about a half hour behind Revere, but the two met up later in Lexington after Revere successfully warned Hancock and Adams of the impending danger. From there, Revere and Dawes set off together for Concord, but they would not be a duo for long because, outside of Lexington, they ran into Doctor Samuel Prescott, who was deemed trustworthy enough that he became the third member of the midnight ride.

It’s a good thing he did, too, because in Lincoln, Massachusetts, the trio was waylaid by a British patrol. They rode off in different directions hoping one of them would make it and it was Samuel Prescott who managed to break through the roadblock, ride to Concord, and deliver the message. That’s right – Paul Revere never finished Paul Revere’s midnight ride, despite the poem proudly proclaiming “It was two by the village clock/ When he came to the bridge in Concord town.”

Dawes also escaped the patrol, but got bucked off his horse in the process, so he had to walk back to Lexington. Revere was the only one who was captured. According to his personal account, the British soldiers, led by Major Mitchel of the 5th regiment, interrogated him for a while before riding back towards Lexington together. However, as they approached the meeting house, they were greeted with a volley of musket fire. At that point, the British patrol decided that discretion was the better part of valor, so they changed course to Cambridge. They let Revere go, although they did take his horse, so he, too, had to walk back to Lexington. And, thus, the midnight ride came to an end.

Life after the Ride

The midnight ride might be over, but the war just started. Strangely enough, Revere was denied a commission in the Continental Army at first, but he soon found an even better way of helping the Patriot cause – manufacturing gunpowder. In past wars, colonists always received a steady supply of gunpowder from England which, for obvious reasons, was no longer the case and gunpowder had become the most valuable resource in the land. Revere traveled to Philadelphia to learn how a powder mill operated, but found himself stonewalled by mill owners who weren’t keen to share the secrets of the trade, even in times of war, out of fear of creating competition for themselves. But by hook or crook, Samuel Adams managed to get his hands on the plans for such a mill and sent them to Revere who used them to set up a new powder mill in Canton, Massachusetts.

Following his efforts, Revere was made a lieutenant colonel with the artillery division in 1776, stationed at Fort Independence and tasked with protecting Boston’s harbor.

Revere’s military service was unremarkable, to put it kindly. Unlike many of his fellow Sons of Liberty, he simply wasn’t a military man. He was kept away from the heavy fighting during the revolution and never rose in rank. His time at the Castle was pretty boring, mostly concerned with maintenance. And when Revere finally did see some action, things didn’t go his way. In fact, words like “fiasco” and “disaster” have been thrown around when bringing up the Penobscot Expedition.

It was the summer of 1779 and a British naval force arrived in Penobscot Bay in Maine, intending to set up a base at the mouth of the Penobscot River. When word reached Massachusetts, they quickly raised an army and sent it to deal with the new threat. Commodore Dudley Saltonstall led the fleet, which consisted of 19 warships and 25 support vessels, Brigadier General Solomon Lovell was in charge of the militia, approximately 1,200 strong, and Paul Revere commanded the field artillery.

The expedition set off on July 19, but it ended up being a complete failure, leading to almost 500 casualties and the destruction of the entire colonial fleet. An inquiry concluded that the main problems were poor communication and disagreements over the best course of action between the land and naval forces. Most of the blame was pinned on Saltonstall for failing to act during key moments of the assault. He was court-martialed and dismissed from the Navy after being found guilty of incompetency.

Revere was also asked to resign his post, which was the polite way of getting the boot. He actually requested a court-martial to prove he did nothing wrong. He finally got one in 1782 and it cleared his name but, either way, the Penobscot Expedition was the last thing he did in the military.

After the revolution, Revere went back to being a businessman and expanded his interests greatly. He opened a hardware store; he began importing and selling English goods. He opened a foundry and a copper rolling mill, although silversmithing always stayed his bread and butter. Iconic American landmarks like the USS Constitution, the Massachusetts State House, and Kings Chapel in Boston all had elements designed and crafted by Paul Revere.

By the turn of the century, Revere had shifted into a more managerial role. He retired fully in 1811, leaving the family businesses in the care of his son, Joseph Warren Revere. Paul Revere died in his home on May 10, 1818, aged 83. Locally, he was remembered as a popular figure and successful businessman, with one obituary stating that “seldom has the tomb closed upon a life so honorable and useful.” Nationally, though, his life and his death passed by mostly unnoticed but 40 years later, a poem turned Paul Revere into a folk hero and national icon.