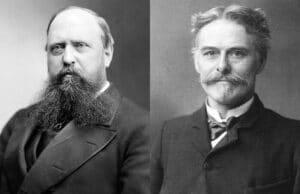

You know what they say – all is fair in love and paleontology. That was the mantra adopted by two of America’s greatest paleontologists – Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. They were instrumental in establishing and popularizing their field of study. They were responsible for some of the greatest scientific discoveries of the 19th century. And one more thing – they absolutely hated each other.

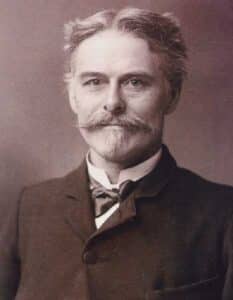

Othniel Charles Marsh

The tale of our little rivalry begins on October 29, 1831, when Othniel Charles Marsh was born in Lockport, New York, to Caleb Marsh and Mary Gaines Peabody.

Marsh had a frugal upbringing. His mother died a few years after he was born, so his father remarried and moved to Bradford, Massachusetts, where his businesses never seemed to take off the ground. Financial struggles were a constant for the Marsh family, so young Othniel received a modest education within their means.

All of this changed in 1851, however, when fate smiled on him by sending him a rich, generous uncle. And by “rich” we mean one of the wealthiest bankers in the country “rich” – George Peabody. In his later years, Peabody became a massive philanthropist, and the causes he took under his patronage were housing for the poor and education. Naturally, who better to be on the receiving end of his generosity than his own kin, so Peabody paid to send Othniel to the best schools in the country – first, to the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and then, to Yale University.

From a young age, Marsh was attracted to natural history. As a child, he often neglected his chores on the family farm and, instead, made trips to the woods to study the local flora and fauna. However, he didn’t focus on paleontology from the start. In his day, paleontology was still a recent field of study, and some of his first scientific papers were on minerals. After graduating from Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School in 1862, Marsh decided to continue his studies in Europe, primarily Germany. Some say he did this to avoid the draft during the Civil War, while others think he was already too blind to be of any use. Who knows?

Either way, the interesting thing about his time in Europe is that this was the first time that Marsh met the man who would become his ardent rival – Edward Drinker Cope, and we’ll get to him in a moment. Their initial encounter occurred in the winter of 1863, in Berlin, at an unremarkable scientific gathering. Marsh and Cope got to talking and discovered they shared similar interests, particularly studying fossils. They parted amicably and even kept corresponding afterward. Little did either of them know what a drastic turn their relationship would take in the future.

Marsh returned to the United States in 1865 after persuading Uncle Morbucks to build a natural history museum at Yale University – named the Peabody Museum of Natural History, it still is, to this day, one of the grandest museums of its kind in the entire world.

Unsurprisingly, that kind of gift earned Marsh a position at Yale, but there was one tiny problem. Paleontology was the “hot thing” in the scientific community but Yale did not teach the subject. Therefore, in 1866, the university created the first professorship of paleontology in America especially for Marsh. Because again, his uncle built a museum for them. However, they did not give him a salary, but this worked out in Marsh’s favor. He wasn’t what you would call a people person. Marsh felt much more at home in his laboratory alone with his fossils than in a classroom filled with doe-eyed students. Fortunately for him, his inheritance from his uncle meant that he didn’t have to worry about money and could focus entirely on his research. Theoretically, he was set up for life…if not for his enmity for a certain other paleontologist.

Edward Drinker Cope

It is now time to meet the second character of our little dyad – Edward Drinker Cope. Born nine years after Marsh, on July 28, 1840, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the differences between the two men were evident from the outset. Unlike Marsh, Cope was born into a wealthy Quaker family, so young Edward benefited from a thorough education from an early age and, indeed, had already published his first scholarly article by the time he was 18.

There was, however, one problem that Cope and Marsh shared – both of their fathers wanted them to take over the family farms. For Marsh, this seemed more like a necessity than anything else until his rich uncle started signing checks. As far as Cope was concerned, his father envisioned him as a “gentleman farmer;” in other words, he would have simply been a rich landowner who did a bit of farming on the side, while somebody else did all the grunt work. It certainly would have been starkly different to Marsh’s circumstances, but even that lush position held no interest for Edward Cope as he developed a love for natural history.

To be fair to his parents, they certainly did encourage this passion in young Edward by taking him and his siblings to museums, gardens, and zoos all over New England to foster his curiosity about the world around him. Unsurprisingly, the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia became one of Edward’s favorite hangouts and he began working part-time there in 1858. Eventually, his father gave up hopes of Edward following in his footsteps and agreed to pay for his son to continue his scientific education at the University of Pennsylvania.

There, Edward studied under Joseph Leidy, one of the most eminent anatomists of his day who also happened to be a paleontologist, who likely encouraged Cope to pursue this avenue of study. Similar to Marsh, Cope adopted a buffet-style approach to natural history and tried a little bit of everything – herpetology, ichthyology, ornithology, before he finally focused on paleontology.

Then, during the early 1860s, Cope was sent abroad by his father to avoid the Civil War, although, to give him partial credit, he wrote back of his intention to return and enlist. He just took his sweet time and, by the time he was back in the country, wouldn’t you know it – the war had ended.

As we already stated, Germany was where he first met his future rival. Their initial meeting was amicable and they continued corresponding afterward, although this was fairly one-sided, with Cope doing most of the writing. Their personalities also stood in contrast to each other, with Marsh being the taciturn loner who only communicated with the outside world as much as strictly necessary, whereas Edward Cope was the outgoing type, described as “warm but impetuous,” who may have seen in Othniel Marsh a colleague, a future collaborator, and, perhaps, even a friend…Boy, was he wrong!

The Butthead Elasmosaurus

![]()

When Cope returned to the United States, he secured a position as a professor of comparative zoology and botany at Haverford College, a Quaker school in Pennsylvania where his family had connections. He also married a woman named Annie Pim in 1865 and had a daughter named Julia together, another point of contrast to the lifelong bachelor Othniel Marsh. Cope enjoyed teaching and yet he only held the position at Haverford for three years because, unlike his rival, there was something he loved even more – being out in the field. To Cope, true paleontology wasn’t done in a dark and dingy laboratory but on dig sites where you could get some dirt on your clothes.

Cope undertook frequent trips to Haddonfield, New Jersey, one of the country’s top fossil sites at the time. That was where his mentor, Joseph Leidy, had found and described some of the first dinosaurs discovered in North America, and the two of them traveled to Haddonfield many times when Cope was still a student. It was, for lack of a better term, his “happy place,” so, naturally, he wanted to share it with his new acquaintance, Othniel Marsh.

Cope brought Marsh along during one of his excursions and, at first, it seemed like the beginning of a beautiful friendship. The two excavated together, they found fossils together, and they even named discoveries after each other. In 1867, Cope described an amphibian he called Ptyonius marshii, and the following year Marsh returned the favor with a giant reptile named Mosasaurus copeanus.

But unbeknownst to Cope, there was treachery afoot. Because Marsh liked the dig at Haddonfield so much that he wanted it all for himself. So he went behind Cope’s back and bribed the site managers to send all the bones they found directly to him. As far as we know, this was the first transgression between them, an act which Cope later deemed “the beginning of the end of their friendship.” But even with the stab wound in his back still fresh, Cope was about to receive another blow, this was far more public and humiliating which would permanently solidify the spiteful rift between the two men.

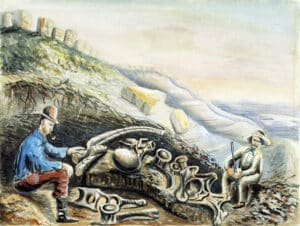

Even with his fossil stash in New Jersey usurped, Cope still had bones sent to him from all over the country and he received one delivery from Kansas which he was certain would make him the talk of the town…which it did, just not in the way he was hoping. In his office, Cope had the bones of the first Elasmosaurus ever discovered. It was a large marine reptile part of the plesiosaur order from the Late Cretaceous period, about 80 million years ago.

Like many other plesiosaurs, it was characterized by a thin, long neck and a relatively short tail…except that Cope didn’t realize that at the time. In his rush to describe the creature, reconstruct its skeleton, and publish his findings, Cope made a very boneheaded mistake – he stuck the head at the wrong end, giving his ancient reptile a short neck and a long tail. Then he wrote a paper on his findings for the American Philosophical Society journal and hosted a little get-together at the Academy of Natural Sciences so people could come see his greatest discovery to date – the Elasmosaurus platyurus.

It was supposed to be a night of triumph for Edward Cope, but it ended up being a giant blunder that dogged him the rest of his career, and it was none other than Othniel Marsh who pointed out his mistake, at least according to him. Of course, Cope didn’t buy it at first. He assumed that his rival was simply trying to embarrass him, so both of them turned to Joseph Leidy to act as arbiter. Despite being Cope’s former mentor, Leidy played no favorites and, according to the story, gave Elasmosaurus platyurus a cursory examination before picking up the head from the short end and placing it at the long end.

It was a point for Marsh who recollected the impact of this incident: “When I informed Professor Cope of it, his wounded vanity received a shock from which it has never recovered, and he has since been my bitter enemy.”

Utterly humiliated, Cope published a quick correction and tried to purchase all of the copies of the American Philosophical Society journal with the error, but it was too little, too late. To further add to his embarrassment, Leidy also corrected him in print, which does beg the question – why didn’t he become the target of Cope’s wrath instead of Marsh? Maybe Cope simply had too much respect for the man who likely made him want to become a paleontologist. This is mostly speculation, but the people who knew all the men involved opined that Leidy and Cope did not have such a personality clash as Marsh and Cope had. Leidy was described as a “gentle and agreeable person” who wasn’t interested in the competitive aspect of scholarly pursuits and even discouraged it in his former pupil; he just wanted to get the science right. Furthermore, given that Cope’s mistake should have been obvious to any self-respecting paleontologist, it was probable that Leidy was aware of it even before the official “unveiling” and may have even warned Cope about it, but the latter was too stubborn and arrogant to listen.

Leidy might not have relished pointing out Cope’s error, but Marsh sure did. As was revealed after his death, Marsh carefully scrutinized all the papers and articles that Cope published and kept a journal with every single mistake he ever made, both big and small. However, it was his “buttheaded” Elasmosaurus that he brought up whenever he wanted to question Cope’s credibility.

Publish or Perish

During the 1870s, the Bone Wars had begun in earnest, as both men made their way westward to look for fossils, particularly in Kansas, Colorado, and Wyoming. The gloves were off and Cope and Marsh were now openly hostile and were constantly looking to one-up each other. If one of them announced that they had discovered a certain type of ancient creature, then the other one would try to find an even bigger animal just to steal his thunder.

This happened in 1877 when just a month after Marsh proclaimed to have uncovered a gigantic dinosaur near Golden, Colorado, Cope announced the discovery of Camarasaurus supremus, which he described as “exceeding in its proportions any other land animal hitherto discovered, including the one found near Golden City.”

Suppose one of them made an error in a published paper. In that case, you can rest assured that the other would publish a correction as fast as humanly possible and usually also include a quick jab at their adversary and the quality of their work. When Cope incorrectly asserted that a new species of a herbivorous mammal he uncovered had a proboscis, Marsh wrote “Surely such an animal belongs in the Arabian nights,” also adding that Cope was almost as well known for his “sharp practice in science … as he is for the number and magnitude of his blunders.”

Unfortunately for Cope, he made it pretty easy for Marsh to target him in print because he undoubtedly made the most mistakes due to his publishing style. Both men valued speed over accuracy as they always wanted to be the first to announce a new discovery, but Marsh did show some restraint in this regard. He preferred to take his time with his writing and save it for some of the more prestigious journals, whereas Cope was definitely quantity over quality. And when we say that, we really mean it. Edward Cope published a staggering 1,400 papers during his career, even purchasing his own journal, The American Naturalist, in 1877, to speed up the process even further. In his haste, a lot of errors slipped through the cracks, giving his detractors i.e. Othniel Marsh, plenty of ammunition to work with.

Don’t get us wrong, Marsh made mistakes, too. They both misidentified fossils, sometimes counting the same animal as two or three or even half a dozen different species, and sometimes announcing a new species based on the bones of an animal that had already been discovered. On at least one occasion, Cope openly accused Marsh of straight intellectual theft, claiming that the latter attended a lecture by Cope on Permian reptiles, then hurried back home to write his dissertation on the subject and used his connections to get it published in the Journal of Science as his own.

While many point out that the Bone Wars led to the discovery of many new species and the popularization of a field of study still in its nascence, it also created a complicated taxonomic mess of wrongly identified animals that required decades for the next generations of paleontologists to untangle.

Field Fracas for Fossils

Of course, print was only one area where Marsh and Cope tried to undermine each other, but if you’re a paleontologist, you can’t write about newly discovered species without fossils, so the other side of the war was fought out in the field. During the first half of the 1870s, Marsh went on excursions that were funded by Yale, as long as he took students with him. Apart from those, he didn’t personally go on many journeys. He found it tiring and a waste of time, instead preferring to work in the lab and have agents send fossils to him. Meanwhile, Cope secured a sweet gig for himself with the precursor of the U.S. Geological Survey under geologist Ferdinand Hayden. It wasn’t paid, but it allowed him to travel to areas of interest and work under the authority of the government.

Unsurprisingly, both men tried to screw over the other by securing the loyalties of each other’s agents and paying them to redirect new fossils to them instead of their competitors. Marsh even went one step further and had spies infiltrate Cope’s camp to keep an eye on him. They developed a code system and everything, referring to Cope as “Jones” in their communications.

The rivalry between the two scientists intensified in 1877 when they found one of the best fossil sites in the world at Como Bluff, Wyoming. The stegosaurus, diplodocus, allosaurus, and apatosaurus were all first discovered there. Unsurprisingly, both men wanted to work the area and neither one intended to share, so they resorted to the same dirty tactics to gain the upper hand – they outbid each other, spied on each other, sabotaged each other, and stole from each other. Their men even got into a rock fight once, but, undoubtedly, the most heinous action from a so-called “man of science” was undertaken by Marsh, who sometimes instructed his field crews to destroy the fossils they couldn’t take with them, just so they would leave nothing behind for Cope’s men.

Mutual Assured Destruction

The digs at Como Bluff lasted for 15 years and they got pretty expensive. Oftentimes, the paleontologists had to rely on their personal wealth to fund these expeditions and they were starting to take their toll, especially on Cope. Marsh landed a plum job for himself in 1882 as the chief paleontologist of the newly created U.S. Geological Survey. Plus, he had the political connections to make sure that Cope couldn’t get any similar positions.

Not that Cope needed Marsh’s interference to go broke. He could accomplish that all by himself through unchecked spending and bad investments. Particularly, he sunk a lot of the family money into silver mining, which went well for a few years during the first half of the 1880s, but soon the mines dried up and Cope’s stocks became toilet paper. Eventually, his family left him, his health deteriorated, he had to mortgage his house and move into a tiny apartment, and start working the lecture tour to earn a living month-to-month.

At this point, we could say that Marsh had won the Bone Wars. It was a pyrrhic victory, for sure, but if we had to raise one man’s arm at the end of the fight, it would be his. If either of them had the slightest bit of common sense, they would have ended the feud here and got on with their lives. Already, each man had more fossils than could fit in his house and the backlog alone would have taken them years to go through. But no, Marsh smelled blood in the water and wanted to go for the killing blow by taking the one thing that Cope had left, which he treasured above all else – his fossil collection.

In 1889, Marsh used his connections to persuade the government that most of Cope’s collection had been secured using federal funding and, thus, rightfully belonged to the government. U.S. Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble wrote Cope a letter demanding that he relinquish his fossils to the Smithsonian Institution, and although it was Noble’s name on the letter, Cope knew very well that it had Marsh’s name written all over it.

Fortunately for Cope, he was a thorough bookkeeper and had the receipts to prove that he had spent over $80,000 of his own money on his fossils. That’s over $2.5 million in today’s money. Furthermore, he had a cache of documents detailing every single injustice, both real and perceived, that Marsh had committed over the decades and decided to go scorched earth on him by sending it to the New York Herald. However, the journalist there had a good nose for scandal and realized that Cope was no innocent victim in this feud as he tried to portray himself. So instead of a hit piece on Marsh, as Cope intended, the Herald ran the story with the headline “Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare,” detailing both of their shameful exploits. Of course, Marsh retaliated with his own accusations in the same newspaper and, for the first time, the Bone Wars were fought out in public, much to the eternal shame of the rest of the scientific community.

This tanked both of their reputations. Marsh was investigated for his frivolous spending on trips sponsored by the U.S. Geological Survey and lost his job with the USGS. Plus, in a fitting display of karma, he had to surrender a part of his fossil collection because, unlike Cope, he really did use government funds to obtain them.

Cope, too, had to give up his beloved bones which he spent decades collecting. Not because he was forced to, but because he was broke. In 1895, he sold most of it for $32,000, much less than the $50,000 he was asking for. He fell ill the following year and died on April 12, 1897, aged 56, ostensibly of uremic poisoning.

Othniel Marsh died of pneumonia just two years later, on March 18, 1899, aged 67, and his collection of fossils was split between the Smithsonian and the Peabody Museum at Yale. These men have been gone for over 100 years, and yet their legacy still puzzles the scientific community. Was their behavior detrimental to paleontology, or was their obsession with each other the main thing that drove them in their careers? As one scientist put it: “Before Cope and Marsh there were just a few dinosaurs known. After them there were hundreds.” It’s not outlandish to say that no other paleontologists shaped our view of dinosaurs more than Cope and Marsh.

So what do you think? Were the Bone Wars a positive or a negative for paleontology?