She put herself in danger in the pursuit of a good story. She uncovered wrongs committed in society. She traveled around the world, and she did it all in a time when women weren’t expected to do anything beyond get married, have children, and take care of their home.

She lived her life differently, and she faced backlash. But she never backed down, and she changed lives and changed journalism forever.

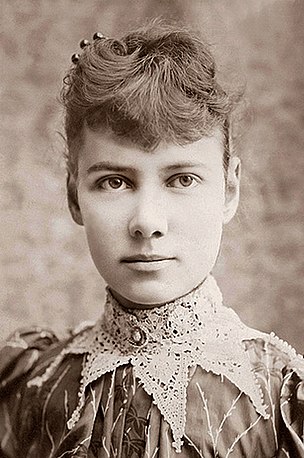

Who was this courageous woman? Nellie Bly…a woman ahead of her time.

Early Life

Though it’s the name she’s best known as, Nellie Bly wasn’t born as such. At her birth in 1864 she was christened as Elizabeth Jane Cochran. And growing up, she was known by yet another name – Pink.

She was a vibrant, energetic child who never shied from attention. Her mother encouraged her vivaciousness, and allowed her to dress in bright colors. Most other girls and women in their hometown of Cochran, Pennsylvania were wearing drab colors of brown, black, gray, and white…

But Pink stood out. She had to, she had 13 brothers and sisters to contend with for attention, after all. The town was named after Bly’s father, Judge Michael Cochran. Judge Cochran passed away at an early age…and Bly was only six years old when it happened.

Her father did not have a will, and his death left the family impoverished. Bly’s mother remarried, but the marriage turned out to be a disaster. Her new husband, Bly’s step-father was a violent drunk. When Bly’s mother had finally had enough of his mistreatment, she filed for divorce.

At only 14 years old, Bly was called upon to testify at the divorce trial. She had to speak up about what she had seen this violent man do, and how he had mistreated her mother. True to her personality even then, she was honest and witty even in what must have been a difficult situation for a young teenager. During the trial, she told the court:

“My stepfather has been generally drunk since he married my mother, and when drunk he is very cross. He is cross sober, too.”

The whole ordeal made an impression on Bly. In the era she was living in, marriage was supposed to be the ultimate goal for a woman. But having seen her mother’s experiences, Bly knew that marriage didn’t always mean a secure future or even happiness.

Bly was going to make her mark on the world on her own.

Journalism Career

Initially, Bly went to school for a career in teaching. For a woman, that was one of the only career paths available. She was a good writer, but she wasn’t a good student. Then, after only one semester she couldn’t afford the tuition, her mother needed her help at home, and she had to leave school.

She moved with her mother and siblings to Pittsburgh, where they ran a boarding house for income.

One day, Bly picked up a local newspaper and was aghast at a column she read.

The title was enough to set her off – “What Girls Are Good For.” The actual contents, well, those were outright angering. The column asserted that women were good for nothing but staying at home and giving birth…and working women? The writer called them “a monstrosity.”

Bly wasn’t one to sit idly by and let something she disagreed with as much as this pass by. She drafted up a response…using the pseudonym “Lonely Orphan Girl.” Her response caught the attention of the paper’s editor, George Madden. But as she had written it under a pseudonym, he had no way to identify and get in touch with Bly. He was so impressed, though, that he didn’t give up…he put an advertisement in the Pittsburgh Dispatch asking “Lonely Orphan Girl” to contact the paper and reveal her identity. Why? He wanted to give her a job.

Bly responded to the advertisement, and was given the chance to write a column on a trial basis. After her first column was published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, Madden hired her for a full-time job.

While at the Dispatch, Cochran officially adopted the name the world came to remember – Nellie Bly.

She was working for $5 a week, but she had a platform to share her ideas about women’s independence. Bly also began the work that would make her famous, outing social wrongs as an undercover reporter. She combined the two messages by going undercover as a factory worker and writing an expose on the poor conditions women faced as they tried to earn pennies to help feed their families. She also wrote about the unfair treatment women also received in divorce proceedings…a topic she knew a thing or two about because of her mother’s experience.

But her articles were controversial. And advertisers don’t like controversy. They started to pull their ads from the Dispatch, and the publisher got nervous.

If she was going to cause problems for their bottom line, they didn’t see the value in keeping Bly in this role that was so atypical for women at the time. So they put her where women writers usually worked – the fashion and society pages. Bly wasn’t happy with this move. In 1887, at only 23 years old she moved by herself to New York City. She didn’t have a job when she went to the big city…in fact, she was unemployed for months.

She wasn’t willing to give up, though…and kept visiting offices and applying for work. After four months, she hit the jackpot. The New York World offered to let her try out an assignment…

Run by , the paper was a prominent publication. And Bly was up to the job.

One of her first assignments at the New York World became her most famous. It also made a difference for the treatment of some of society’s most vulnerable.

In the late 19th century, the mentally ill were locked up and isolated from society. One place they were sent in New York was the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. And Bly and her editors wanted her to get into the institution.

She was eager to do so, even though she didn’t know how she’d be getting out. All she was told in preparation for the assignment was:

“Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise and blame as you think best, and the truth all the time.”

She spent days preparing, practicing facial expressions to make herself seem as out of it as possible. Then, she went to a boarding house to spend the night. While there, she pretended to be afraid of everything at the house. She spent hours just staring at the wall, saying nothing. In short, she did her best to just act insane.

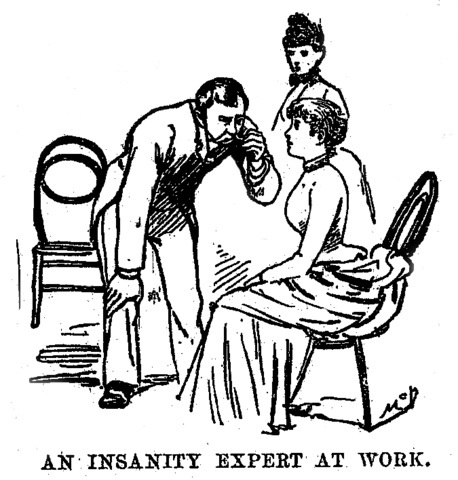

It worked. The head of the boarding house called the cops, and Bly was taken away…the police had her analyzed by doctors at Bellevue Hospital. Bly claimed to have amnesia, and her case caught the attention of the media, though no one recognized her as a journalist. Ultimately, the doctors recommended that this young, pretty, and apparently insane woman be committed to Blackwell Island.

Even before she arrived at the asylum, she had her first bit of information for her expose – asylums weren’t all that hard to get into. When she arrived there, this observation was cemented for her as she met other patients who didn’t seem to have all that much reason to be locked up away from society in an asylum.

Once she was in the asylum, Bly didn’t act at all. She decided to just be herself, but this didn’t arouse suspicion that she wasn’t insane. In fact, it did the opposite.

“The more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be,” she observed.

Daily life was tough at the asylum. Bly was forced into cold baths, and was freezing most of the time she was committed.

“My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold. Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head—ice- cold water, too—into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth.”

The food was horrific – dirty water served alongside rotting meat, gruel, and nearly inedible bread. Patients ate in areas surrounded by waste and with rats crawling around their feet. Their days were spent sitting on hard benches, and some patients were tied together.

In her newspaper report, and a later published book, Bly described the horrific treatment of asylum patients … and how it might be making the patients even worse:

“What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. until 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.”

Bly lasted ten days at Blackwell Island. She was released when the paper contacted the asylum and asked for her release. Soon after, her expose was published in the New York World and the piece grabbed attention around the country.

People were outraged, and were calling for change. A grand jury was convened, and Bly joined them in devising a series of changes that needed to be made at the asylum. The New York Department of Charities and Corrections had a million dollars added to its budget to help with improvements to the facilities it oversaw, and overall safer and more humane conditions and treatment were implemented at asylums.

Bly became a celebrity – she was praised for her bravery and for her willingness to speak out about societal ills.

But her work was far from over. Even with her fame, she kept up her undercover reporting.

The same year she went undercover at the asylum, Bly also went undercover for a piece of a lighter nature. She wanted to find out about the active industry in New York City that sought to find women husbands.

“This husband-getting interested me. I did not want to marry, but I was as interested as a little boy with a dynamite cartridge.”

On another occasion, she wrote about a sadder New York industry – baby buying. And she took on the New York government, exposing the actions of a prominent lobbyist who was essentially bribing lawmakers.

Nellie Bly had no shortage of topics to write on, and no shortage of courage to drive her forward in her investigations. But her appetite for adventure wasn’t fully sated by writing articles about the seedy goings-on of New York City.

Traveling the Globe

In 1888, she was 24 years old and she had an idea. She wanted to travel around the world, and she wanted to do it faster than Jules Verne’s fictional character Phileas Fogg had. And, of course, she wanted to write about her adventure for the paper.

Even though she’d proven herself with her past assignments, Bly still faced reticence from her editors. Women working was quite different for the times…women traveling by themselves was adding a new layer of defiance to norms. They wanted to send a man around the world, not Nellie. As she later wrote, the reaction to her request was along the lines of:

“It is impossible for you to do it,’ was the terrible verdict. ‘In the first place you are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes. Besides you speak nothing but English, so there is no use talking about it; no one but a man can do this.’

Her response?

“Very well. Start the man and I’ll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him.”

It took a year before her editors could be convinced and she took off on her journey. At that time, women traveled with suitcases full of clothes, and were often attended to by escorts. But Bly again showed she was ahead of her time. When the time came for her to depart on her trip around the world in 1889, she boarded the ship Augusta Victoria by herself and with only two small bags. She wore a dress and an overcoat, and kept a few hundred dollars in a bag tied around her neck.

The first part of her trip was tough. Bly got seasick, and couldn’t hold down food. The only thing that made her feel better was sleeping…at one point, she slept for so long the ship’s crew thought she had died in her cabin.

She landed in England, then went on to France. In France, she met Jules Verne, the man who inspired the trip. From France, she traveled to Egypt, Ceylon, Hong Kong and Japan. In China, she visited a leper colony. Along the way, she traveled aboard ships and rickshaws and trains, even riding horses when she needed to. Back home in the United States, her readership was kept updated via telegraph.

All the time Bly was traveling the world, people were keeping a close eye on the dispatches she sent from abroad. They had more than a passing interest in her venture…there was a prize at stake. The New York World had decided to make the most of Bly’s trip to drive up their audience and build their brand…they offered a trip to Europe for the person who was closest to guessing Bly’s return time to her starting point. People made guesses literally down to the second.

Meanwhile, they were also following another trip around the world. Upon hearing of Bly’s stunt, a rival New York newspaper decided they couldn’t let the New York World get all the attention. So they sent a female reporter of their own around the globe. Elizabeth Bisland left New York heading the opposite way, traversing the United States first before heading across the Pacific. Bisland took four days longer than Bly to travel the world.

The final leg of Bly’s global trip was a journey across the Pacific Ocean. She made her way across the world’s largest ocean on board the RMS Oceanic, but the ship hit rough weather on the crossing. Bly was two days later than she had planned for her arrival back in the United States. She disembarked in San Francisco, and boarded a private train to take her back to the east coast.

72 days after departing aboard a ship in Hoboken, New Jersey…she was back. Not only had she beaten Phileas Fogg’s fictional record, she had set a world record of her own.

She had once again proven her naysayers wrong.

“I always have a comfortable feeling that nothing is impossible if one applies a certain amount of energy in the right direction. When I want things done, which is always at the last moment, and I am met with such an answer: “It’s too late. I hardly think it can be done;” I simply say:

“Nonsense! If you want to do it, you can do it. The question is, do you want to do it?”

Bly published a book about her adventure, and the New York World was happy with the increased attention they received thanks to Bly. But they weren’t happy enough to give Bly a bonus.

Insulted, she resigned.

She didn’t have a job, but she wasn’t suffering. Quite the opposite – she had become a national celebrity. Her image and her name were worth money, so popular had she become with her adventure around the world. She wasn’t even thirty.

Within three years of her departure, the New York World wanted her back. She started writing for the paper again in 1893, once again taking on investigative assignments that helped root out corruption and mistreatment.

Marriage and Industrialism

Though she had always said she had no plans to marry, and had indeed lived out her life in defiance of the expectations of women, Bly eventually met a man and decided to settle down.

In 1895, she met and married a 73-year-old man. Bly was just 31. Her husband, Roger Seaman, was head of The Iron Clad Manufacturing Industry. Marriage didn’t mean that Bly was ready to become a housewife and not work…quite the opposite, in fact. She started to get involved with the manufacturing company, offering designs for products and helping oversee its operations. Two of the designs she created for the company were patented, a milk can and a garbage can. In 1896, she quit working for The New York World to focus more of her time on the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company. When her husband died in 1904, she even took over as its president. Her time in that role lasted less than a decade though, as the company filed for bankruptcy in 1911.

When the company failed, Bly jumped right back into what she knew best – reporting. The women’s suffrage movement was in full swing, and Bly wrote about the marches and calls for the vote. In the latter half of the 1910s, she covered World War I…giving her another groundbreaking title. She was the first female war correspondent in the United States.

Fully back in journalism, she got her own column in the New York Journal in 1919, but sadly her return to writing didn’t last long.

In 1922, when she was only 57 years old, Bly contracted pneumonia. This illness would prove to be the only thing that could keep her down. On January 27th, 1922, Bly lost her life to pneumonia at St. Mark’s Hospital in New York City.

Fittingly, the next day’s edition of The Evening Journal called her “The Best Reporter in America.”

Legacy

Nellie Bly was a trailblazer, not just for women, but for all journalists. Her writing made a difference in people’s lives – effecting change in government, and inspiring and lighting people’s imaginations. From an early age, she showed great courage. She knew what she wanted, and she went for it, letting nothing – especially not the fact she was a woman – stand in her way.

As a writer, perhaps her own words sum up her life best:

“I said I could and I would. And I did.”