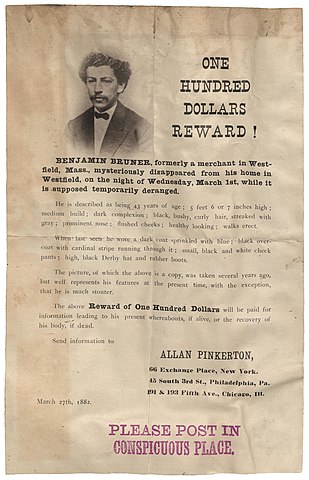

“We Never Sleep.” That was the slogan that greeted everyone who walked through the doors of the most famous detective agency in the world, the Pinkertons. Not to mention that their logo of a vigilant, unblinking eye gave the world the term “private eye.”

The detective agency was founded by Allan Pinkerton, a Scottish immigrant and our subject for today. He came from humble beginnings, and he led a quiet, remote life building barrels until fate thrust him into the middle of the action. And, as it turned out, Pinkerton took to adventure like a duck to water.

Early Years

Allan Pinkerton was born on August 25, 1819, in Glasgow, Scotland, in one of the poorest and most crime-ridden areas of the city known as the Gorbals. He was the second of two sons of William Pinkerton and Isobel McQueen alongside Robert Pinkerton, who was five years older than him. His father’s job is somewhat uncertain – some sources said he was a police sergeant, others that he was a jailer. Either way, what mattered was that William Pinkerton was injured on the job, and he died when Allan was still a child, leaving the family in dire financial straits.

Both Pinkerton boys had to find work, which meant that Allan had to forgo finishing school in order to support his family. Allan showed up in the 1841 census, with his occupation listed as a journeyman cooper, aka a barrel maker, while his older brother was a blacksmith. For some reason, a nine-year-old boy named John Robertson is also listed as part of the household, although we are not exactly sure where he fits in since the census didn’t include the relationships between family members. Records also show that Allan Pinkerton married the following year to a woman named Joan Carfrae, another native of Glasgow. The two stayed married until his death and had three children together.

While working as a cooper, Allan Pinkerton became involved in Chartism, a movement for reforms that benefited the working class. As you might expect, the government was not too thrilled with this development and tried to suppress this new crusade as much as possible. Although many Chartist protests were peaceful, there was the occasional dust-up with the police. Things took a turn for the worse in 1842, after the Chartists gathered over three million signatures for their petition to be discussed in Parliament, yet were still turned down. This led to a wave of strikes and riots throughout the UK, and the state responded in kind by arresting many men involved with the Chartist movement.

Following a scuffle with the law, Allan Pinkerton found that a royal warrant had been issued for his arrest so, with few other choices, he decided to leave Scotland under the shroud of darkness and sail to America with his new wife, thus beginning the next chapter of their lives. Given his circumstances, it is bitterly ironic that the Pinkertons themselves would eventually become anti-union hired goons, used as tools by American industrialists to oppress the working class.

Barrels Ahead

Pinkerton’s arrival to the New World was inauspicious, to say the least. He had to work as a cooper on the ship in order to pay for passage for himself and his wife. After a four-week voyage, the vessel got caught in ice off the coast of Nova Scotia, forcing all the passengers to leave everything they had behind and row to safety in lifeboats. In Pinkerton’s own words, by the time the trip came to an end in Montreal, they only had “(their) health and a few pennies.” The newlyweds’ intended destination was Chicago because Pinkerton had a friend there – “auld Bobbie Fergus from the Gorbals.” However, they had to spend an extra week in Montreal, so the cooper could work a bit and earn enough money for the trip to Illinois.

Things went better for the Pinkertons once they reached Chicago. Fergus allowed them to stay with him until they got settled, and he even found Allan a job with Lill’s Brewery – once again, as a cooper. This was their life for about a year or so but, eventually, Pinkerton thought that he would be more successful if he opened his own cooperage. Consequently, in 1843 the couple relocated to the small town of Dundee, in Kane County, Illinois, which, as you might guess from the name, was mainly inhabited by Scottish immigrants. There, Allan Pinkerton built a little cabin for himself and for Joan next to the Fox River, right in the path of ranchers and farmers traveling to-and-from the market. He also had a shed where he toiled every day from sun-up to sun-down – wake up at 4:30, go to bed at 8:30, seven days a week. No drinking, no smoking, no dancing, no shenanigans of any sort – just all barrels, all the time. That was Pinkerton’s regimen and, with that kind of dedication, his cooperage business thrived. His wife considered those days the best of their lives, but destiny had other plans.

The career switch to private eye landed in Pinkerton’s lap by chance. He knew of this little, remote island that had good trees, which he often visited for lumber. One day in 1847, he noticed that somebody else had been there, as well, and had left behind the remnants of a campfire. Pinkerton’s curiosity was piqued, so he returned several times, all sneaky-like, trying to see who else was coming to his secret spot. After a few failed attempts during the day, he decided to try it at night and he hit paydirt – Pinkerton had stumbled upon a ring of counterfeiters. He notified the Kane County Sheriff, Luther Dearborn, and together they staked out the island again. After the sheriff witnessed the criminals firsthand, he formed a posse and took down the entire ring.

Pinkerton received a lot of the credit for the bust, but even so, he still intended to return to his old job. However, a short while later, he got his second case, once again without him actually looking for one. The owner of the general store in town asked him for help identifying another counterfeiter. Pinkerton was reluctant, but he agreed. Not only did he identify the criminal – a man named John Craig – but he also gained Craig’s confidence and arranged for a deal in Chicago where the counterfeiter was arrested.

Ultimately, Craig escaped custody after bribing a policeman, but Pinkerton’s reputation as the local shamus was made. After that, the cooper still wanted to go back to his cooping ways, but this time he wasn’t as sure as before. All of a sudden, life in the middle of nowhere, building barrels from dusk ‘till dawn seemed a little boring. Therefore, when Sheriff Dearborn offered him a position as a deputy, Pinkerton jumped at the chance. He still built barrels, but he swapped his tools for a cudgel when the sheriff had need of him.

Around the same time, Pinkerton became involved with the Underground Railroad, the secret network used to help slaves escape into Canada or the American free states. As a staunch abolitionist, Pinkerton remained involved with this movement for decades and often offered his home as a safe house. This brought him into some conflict with the Dundee Baptist Church. They already weren’t fans of him because Pinkerton was not a religious man, but he also wasn’t the calm and subtle type. Allan Pinkerton was a roaring, angry Scot, and if he had a problem with you, best believe that he would let you know…loudly. The relationship between the two sides worsened when the elders of the church began accusing Pinkerton of selling “ardent spirits,” when, in fact, the cooper was a teetotaler who never touched alcohol. Pinkerton started to get fed up with life on the frontier and even his beloved cooperage business was getting a little monotonous. But fate once again intervened, and Pinkerton was offered the position of deputy sheriff in Cook County, headquartered in Chicago. He accepted on the spot and, soon enough, he sold his cooperage, packed everything into wagons, and moved back to the big city.

Allan Pinkerton, P.I.

This time, Pinkerton worked full-time as a deputy sheriff and he impressed a lot of people with his courage, integrity, and love of a good fight, even when it was against armed thugs. This earned him quite a few enemies and even an attempt on his life when someone tried to shoot him from behind. Fortunately for Pinkerton, he was in the habit of walking with his left arm behind his back, so the bullet hit his hand and didn’t penetrate further. The Chicago Daily Democratic Press reported on the incident:

“The pistol was of large caliber, heavily loaded, and discharged so near that Mr. Pinkerton’s coat was put on fire. Two slugs shattered the bone five inches from the wrist and passed along the bone to the elbow where they were cut out by a surgeon together with pieces of his coat.”

For his efforts, in 1849 Pinkerton had the honor of being appointed Chicago’s first police detective. He only held the position for one year, though, before leaving due to “political interference,” as he put it, but his reputation was enough to immediately secure him a new post as a special agent with the United States Post Office.

Once again, Pinkerton excelled at his job and earned mentions in the local press, which boldly proclaimed that “as a detective, Mr. Pinkerton has no superior, and we doubt if he has any equal in this country.” With that kind of praise being lavished on him, the ambitions of the former frontier cooper grew and, soon enough, he had quit his job with the post office in order to open his own detective agency in the early 1850s. Alongside Chicago attorney Edward Rucker, Allan Pinkerton founded the North-Western Police Agency, quickly rebranded to the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in order to take full advantage of his name recognition. Contrary to popular belief, though, this was not the first known private detective agency. In Europe, French criminal-turned-criminalist Eugène Vidocq (whom we’ve covered on Biographics, just FYI) beat him by a couple of decades, and even in America, there was a pair of St. Louis policemen who opened their own “private guard service” during the 1840s.

The first years of the agency’s existence were fruitful and efficient, but not exactly full of high-stakes, skin-of-your-teeth action. Most of their work was done for the ever-expanding railroads, and it involved either protection services or theft investigations. This was the main course, complemented with side orders of fraud, counterfeiting, bank robbery, and even the occasional murder. The company’s initial success and steady growth allowed Pinkerton to build up a network of underlings he could trust, including Kate Warne, America’s first female detective.

Oddly enough, Pinkerton’s most exciting exploit at this time did not even involve his detective agency, but rather his anti-slavery activities. Pinkerton was well-acquainted with John Brown, arguably the most radical abolitionist leader in the country, who was more than willing to use violence in order to free slaves. Brown was executed in 1859 after a failed attack at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, where he intended to raid the federal armory, arm the slaves, and stage a liberation movement that would extend as far south as possible. John Brown’s failed raid became a pivotal moment in American history leading up to the Civil War, but he had a lesser-known, successful raid earlier in the year which involved Allan Pinkerton.

In January 1859, John Brown led a raid in Missouri, liberating around a dozen slaves. However, his band killed a farmer during the raid, so they had the US Marshals on their trail as they sought to reach Canada. In the early hours of March 11, 1859, the entire group was in Chicago, banging on Allan Pinkerton’s front door. Pinkerton took them all in, no questions asked, but if they were to make it to Canada, they needed money for food, clothes, and supplies, more than Pinkerton himself could provide.

Even so, the detective resolved to get that money, one way or another. He knew there was a Chicago Judiciary Convention scheduled that day, so he sent two friends with a subscription list of all the city’s prominent abolitionists who would be at that meeting. They, however, returned empty-handed, saying that “the delegates refused assistance.” At that point, Pinkerton took matters into his own hands. He tucked his revolver under his coat and traveled to the convention hall, where a hushed silence fell over the crowd as soon as he entered. Pinkerton’s voice boomed throughout the room. He said:

“Gentlemen, I have one thing to do and I intend to do it in a hurry. John Brown is in this city at the present time with a number of men, women, and children. I require aid and substantial aid I must have. I am ready and willing to leave this meeting if I get this money, if not…I will bring John Brown to this meeting and if any US Marshal dare lay a hand on him he must take the consequences. I am determined to do this or have the money.”

Everyone there knew Pinkerton better than to call his bluff so, slowly but surely, almost every politician, judge, and businessman in the room approached the detective and dropped a bill in his hat. A few minutes later, Pinkerton left the convention hall with $500-to-600, and then he escorted Brown and this troop out of the city.

We Never Sleep

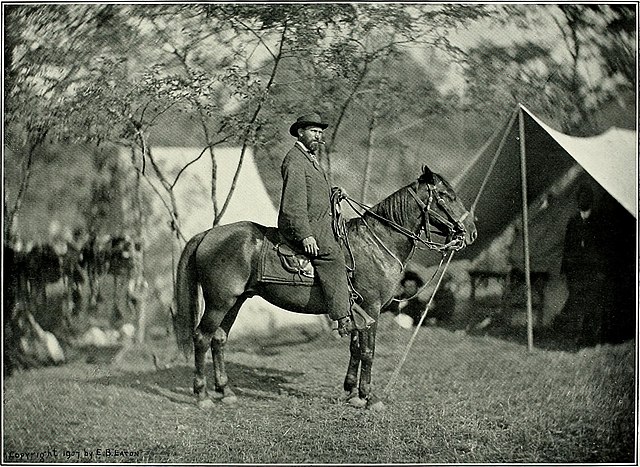

When the American Civil War erupted in 1861, Allan Pinkerton fought on the Union side. No surprises there, given his strong feelings vis-a-vis slavery. He served as head of the Union Intelligence Service for the first few years of the war, under Commanding General George McClellan, who already had a cordial relationship with Pinkerton from their pre-war days when McClellan worked as a railroad engineer and threw a lot of business Pinkerton’s way. The intelligence agency served as a forerunner to the US Secret Service, but its most famous (some would say infamous) moment actually came before the Civil War even started, when Pinkerton and his network of spies may have saved the life of new President-elect Abraham Lincoln.

It became known as the Baltimore Plot and, ostensibly, it was an attempt to assassinate Lincoln while passing through Maryland on his way to his inauguration as the 16th President of the United States. As we said, this was before the Civil War had started which, in the minds of many, had become an inevitability at that point, but some still believed that they would be able to stave off the secession of the Confederacy if they got rid of Lincoln. As you’re probably aware, Lincoln was not assassinated (not in 1861, anyway), and, since nobody was ever convicted and no solid evidence was ever found, there is still an ongoing debate whether or not the Baltimore Plot was even real.

The idea that Lincoln wasn’t very popular in slave states was hardly a shocking revelation. Immediately after winning the election, scores of hate mail and threats began pouring into his office, enough to give Twitter a run for its money. But it was Samuel Morse Felton, President of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad, who heard rumors that something more concrete and sinister was being planned. Because Allan Pinkerton had extensive experience providing protection for trains and his aggressive anti-slavery sentiments were beyond any doubt, it was natural for Felton to turn to him for help. The detective used several of his agents to infiltrate rallies, hangouts, secret societies, and any other pro-slavery meetings and gathered enough information to believe that the threat was real and that the attack would happen in Baltimore.

Why Baltimore, I hear you ask? Well, in February, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln had embarked on a 70-stop railway tour of the country, starting in Illinois and culminating with his inauguration in Washington, DC. That included a lot of places where he could have been waylaid, but Baltimore was the perfect spot for two reasons: one, Maryland was a slave state full of people who hated Lincoln’s guts; and two, there was a city law that forbade steam engines from passing through town so, even if Lincoln was aware of a plot against him, he still had no choice but to get out of his train, get into a horsedrawn railcar, ride that until the end of town, then get out again and enter a waiting steam train. That created a lot of opportunities for an ambush and Pinkerton became convinced that an assassination attempt would take place in Baltimore.

It was on February 21, 1861, that Pinkerton met Lincoln for the first time and brought the threat to his attention. The President was in Philadelphia, in the middle of his whistle-stop tour, and was staying at the Continental Hotel. The problem was that Lincoln’s itinerary and schedule had been published in the press, so his would-be killers knew where he would be to the minute. Pinkerton urged him to change his routine and make an unannounced pass through Baltimore, but Lincoln was reluctant to do so. However, later that same day, he received a letter from Senator William H. Seward, his soon-to-be Secretary of State, who had investigated the threat on his own and pretty much told him the same thing as Pinkerton.

This swayed Lincoln so, the following evening, the President secretly met with Pinkerton and the detective escorted him to the train station where Lincoln put on a disguise and boarded a different train that passed through Baltimore at night. Once the president was out of Maryland, Pinkerton wired a telegram that simply said “Plums delivered nuts safely,” which, presumably, would make Lincoln the “nuts.” Meanwhile, the president’s retinue and his family boarded their scheduled train the following morning and Lincoln made it safely to his inauguration.

Kate Warne, the aforementioned female detective, accompanied the nutty president on his trip. According to legend, she never closed an eye while Lincoln was in her charge, hence the Pinkertons’ slogan “We Never Sleep.”

Post-War Proceedings

Whether or not the Baltimore Plot truly existed we cannot say, but it certainly convinced Lincoln of Pinkerton’s detective bona fides, which was why he was put in charge of Union intelligence. During the early days of the war, Pinkerton personally led the investigation that exposed a spy ring in Washington. However, he didn’t really cover himself in glory when he was sent to the frontlines, alongside the Army of the Potomac. It turned out that military espionage, done amidst the chaos and confusion of war, wasn’t really his forte. It wasn’t for lack of bravery. Several times, Pinkerton went into enemy territory himself to gather intelligence, despite the high likelihood that he would be recognized. However, his reports with estimates on enemy size and movements were often filled with errors or exaggerations and, during war, that kind of stuff was pretty important.

At the same time, Pinkerton found himself trapped in a political war. He was an ardent ally of the aforementioned General George McClellan, but McClellan and Lincoln didn’t get along at all. Eventually, the general was relieved of his command, and when McClellan left, so did Pinkerton.

Even so, following the war, demand for the Pinkertons was high. However, by this point, the company grew to the point that Allan Pinkerton mostly delegated to other people. He rarely did any grunt work himself and spying was out of the question since he had become too well-known. Furthermore, in 1869, Pinkerton suffered a stroke that nearly killed him and left him temporarily paralyzed so, even though he eventually returned to the office, his days of personally chasing down criminals were over. He let his sons, Robert and William Pinkerton, do most of the heavy lifting.

That being said, the Pinkertons had some of their most notorious cases after the Civil War. In 1866, they began pursuing the Reno Gang, who were responsible for the first peacetime train robberies in the country. On this occasion, Allan Pinkerton did join in on the hunt and he almost got shot twice for his troubles but managed to escape unscathed both times.

During the early 1870s, the Pinkertons were put on the trail of the infamous Jesse James and his gang. This case, however, gave the detective agency their biggest black eye with the public. Their first failure occurred in 1874, when an undercover detective named Joseph Whicher was identified and murdered by the James Gang. The vengeful Pinkerton was out for blood, so his men organized a raid on the James farm in January 1875. In a foolhardy move, one of the detectives tossed an explosive into the house, killing Jesse James’s eight-year-old half-brother Archie. With the blood of an innocent child on their hands, the Pinkertons were vilified in the press and Allan Pinkerton gave up chasing Jesse James, suffering a very public and humiliating defeat.

In the minds of the average working man, the Pinkertons would soon gain a sinister reputation; not due to the botched raid, but something else entirely – their violence against the labor movement. Just like he loathed alcohol and slavery, Allan Pinkerton was steadfastly anti-union which, in his mind, did more harm than good to the working class. During the mid-1870s, there was a famous case where a Pinkerton agent named James McParland infiltrated an Irish working-class secret society named the Molly Maguires, collected evidence against them, and got 20 of them sentenced to death for their roles in violent labor conflicts.

From that point on, the Pinkertons became the go-to service for every rich industrialist in the country who wanted to ensure that his workers didn’t unionize. But there was no more espionage, counterintelligence, or any other kind of detective work involved. The Pinkertons were simply armed goons, there to break up any would-be strikes, almost always using violence.

Allan Pinkerton defended these actions until his dying day, which occurred on July 1, 1884. Some said that he died from gangrene of the tongue, after biting it during a fall, but others reported a more mundane cause of death such as a stroke or malaria. After his death, his sons took over the company and maintained their strikebreaking services, overseeing some of the bloodiest labor union clashes in the history of the country that resulted in hundreds of deaths and injuries and forever tainted the Pinkerton name.