During the mid-1930s, famed mobster Bugsy Siegel left New York and relocated to Los Angeles to look after the mob’s interests in California. The city perfectly catered to Siegel’s love of the good life – lavish parties, nice cars, expensive suits, rubbing elbows with the Hollywood elite. It was all right up Bugsy’s alley, and he practically reinvented the image of the classic mobster.

But he never did it alone because, throughout his entire time in California, Mickey Cohen was his shadow. While Siegel was suave, tall, and handsome, and was able to conceal his dark side from the general public, Mickey Cohen was a lot more “what you see is what you get” – a quick-tempered, loud, boisterous, and violent former boxer who was brought in as Siegel’s bodyguard and quickly rose through the ranks of the mob due to his viciousness and willingness to do whatever was necessary to get the job done.

But Cohen wasn’t just some dumb muscle. When Bugsy Siegel was “forced” into retirement, Moe Greene-style, with a bullet through the eye, a power struggle took place and Mickey Cohen emerged victorious as the new “King of Los Angeles.”

More details

Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen was a gangster based in Los Angeles and part of the Jewish Mafia

Early Years

Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen was born on September 4, 1913, in Brooklyn, New York, the youngest of five children to Max and Fanny Cohen, two Orthodox Jews who had immigrated from Kyiv. His father, who was a fishmonger, died from tuberculosis a year after Mickey’s birth, putting pressure on his mother to provide for the family. When Mickey was six years old, she borrowed some money and relocated from New York to Los Angeles, settling in a Russian Jewish neighborhood in Boyle Heights where the Cohens opened a pharmacy.

While the mother handled the legitimate side of the drug store, Mickey’s older brothers operated a small gin mill, just enough to make a few extra bucks once Prohibition went into effect. This got Mickey his first taste of a life outside the law since he acted as the delivery boy in the operation, and already he discovered that he liked it. He would later recall that he enjoyed the sensation of having a big wad of cash in his pocket, and even when he only had a few hundred bucks, he would keep them in singles and five dollar bills to make the stack as thick as possible. Even getting pinched by the police when he was only nine years old didn’t scare him straight. His brothers got him off with a short stint in reform school, and it then became clear that Mickey Cohen was not meant for a life of walking the straight and narrow.

School meant very little to him, and Mickey encountered little resistance from his family when he dropped it altogether at the age of 10. His mother worked upwards of 14 hours a day and barely saw him, while his older siblings all had their own side hustles going and hadn’t exactly been valedictorian material, either. His sister Pauline was the only one who tried to guide Mickey onto a more righteous and straightforward path but to no avail.

When he wasn’t bootlegging, Mickey worked as a newsboy and soon realized that the job was a lot more physical than one would expect. He constantly had to fight with other newsboys in order to work the best street corners and that’s how Mickey discovered that he was pretty good when it came to swinging his fists. He started boxing, taking part in unofficial cards throughout the city to supplement his income.

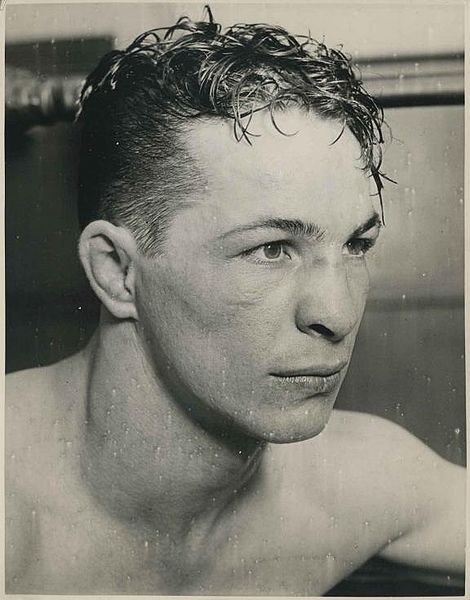

In 1929, the 15-year-old Mickey moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and started training for a legitimate boxing career. He had his first professional match on April 8, 1930, billed as “Irish Mickey” Cohen, for some reason, although sometimes he also went by “Gangster Mickey” Cohen. The fight was a win against Patsy Farr and, maybe, for a time, Cohen thought that a prizefighting career might be in the cards for him. That idea, however, was dropped like a lead balloon in 1931, when Cohen faced off against future world featherweight champ Tommy Paul, and Paul knocked him out so hard that Cohen had to be carried to the locker room while little stars circled around his head…we assume, we’re not doctors.

Anyway, it became clear that Cohen wasn’t championship material, but that did not mean that he was ready to give up on his career completely. According to boxing records, Cohen had his last fight on September 6, 1935, against Tracy Cox. He finished with a record of 8-16-5: eight wins, 16 losses, and five draws, but considering how common match-fixing was back then, it’s impossible to tell how many results were legit.

That being said, fixing fights did have its benefits because it introduced the up-and-coming boxer to some members of the underworld. Therefore, when Cohen decided that life inside the squared circle wasn’t for him, he already had a new career lined up.

The First Mob Years

After he received a drubbing from Tommy Paul, the quality of Cohen’s boxing fights decreased sharply. He turned from a promising pugilistic prospect into one of the many downtrodden low-card tomato cans who didn’t know where their next meal was coming from during the Great Depression. Smaller fights meant smaller purses which, in turn, meant that Cohen needed to find new ways to make money. He and a few of his pals started holding up bookies, speakeasies, and other shady joints, not realizing that most of the places he hit were owned by the mob. Cohen got off easy, though, because the gangsters he targeted had an eye for talent, so instead of making him sleep with the fishes, they put him on the payroll.

Mickey Cohen was now an enforcer with the Cleveland mob, but this role was short-lived. After beating the rap on an armed robbery charge, Cohen decided it was best to lay low for a while, so he relocated to the Windy City where he became a part of the Chicago Outfit. Cohen claimed to have received a personal endorsement from Al Capone himself, who first greeted him by grabbing Cohen’s head in his hands and kissing him on both cheeks. However, Al Capone was imprisoned in early 1932, so the years don’t exactly line up. To be honest, Cohen’s timeline throughout the whole 1930s is a bit screwed up. Suffice to say that he bounced around between Cleveland, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles in that decade. The exact years are uncertain.

More details

Close up of Tommy Paul. Credit: Jtjr17 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Back in Chicago, Cohen mainly handled gambling operations, running card games and crap tables for the Capones. He knew he made it into the big leagues when he survived his first assassination attempt (the first of many, by the way). Here is how Cohen described the event:

“I had on a camel hair coat that, boy, I was really in love with… and I think this was the second time I had worn it. So when they came by shooting, I didn’t even fall because I didn’t want to get my coat dirty!”

Once again, it was decided that it would be better for Cohen to seek safer pastures, so he returned to Cleveland where he ran with bootlegger Lou Rothkopf for a while. But bootlegging wasn’t what it used to be, now that Prohibition was over, so Rothkopf introduced Cohen to some of his New York associates, including Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano, since they were always on the lookout for new muscle. And, as it happened, they had the perfect job in mind for Mickey…

LA Confidential

In 1939, Mickey Cohen moved back to Los Angeles with the task of acting as bodyguard to Bugsy Siegel. By that point, the Commission had been formed and the National Crime Syndicate was in full effect. Lucky Luciano was the most feared man in New York City while Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel were two of his strongest allies. And if you’re not really sure what any of that means, then maybe you should check out the videos we did on each of them because we went in-depth with the formation of the Commission there, so we are not going to retread the same ground. Suffice to say that Bugsy Siegel arrived in Los Angeles with the full support of the New York families with the goal of bringing organized crime in Southern California into the 20th century.

That’s not to say that Los Angeles didn’t have its own crime family. It did and it was run by a man named Jack Dragna. But Dragna was one of those old school Sicilians who still ran the same rackets that had been around for decades, even shaking down immigrants who came into the city. He didn’t have the business acumen of Meyer Lansky, the vision of Lucky Luciano, the muscle of Al Capone, or the political connections of Frank Costello. As one mob historian put it, “Dragna rose to the top among the ‘homegrown’ California mobsters only because he was the best of a poor lot.”

But that was simply not good enough, anymore, and jokers like Siegel and Cohen were there to give Los Angeles a better class of criminals. This didn’t mean all-out war, though. Dragna simply didn’t have the muscle for it, even though he had the backing of the Chicago Outfit. Instead, he just had to grin & bear it and entered into a not-so-friendly rivalry with the New Yorkers.

While Siegel was mostly busy delegating orders and hanging out with movie stars, Mickey Cohen was the one who led boots on the ground – robberies, narcotics, gambling, prostitution, murder – he was involved in all of it. And that’s not taking into account their legitimate businesses, which ranged from fancy dinner clubs to ice cream trucks.

One of the most lucrative operations that the two sides fought over was the “race wire” – the wire service used by bookies for scores and race results. Dragna backed the Continental Press Service, owned and operated by one of his associates, James Ragen, while Cohen and Siegel pushed their own Trans-Continental Wire. Eventually, Cohen decided to put a permanent end to the feud by raiding the Continental Press office, beating up everyone inside, and tearing out the phone lines. Ragen got the message loud and clear – he abandoned the business and left Los Angeles, fearing for his life. He was gunned down in 1946 in Chicago; his killer was never identified.

Cohen had several run-ins with the cops during this time. He was arrested or questioned on multiple occasions, including for two murders, but none of the cases ever went to trial. Cohen liked to brag in private that it cost him 40 grand to get away with murder.

On a personal level, Mickey Cohen married Lavonne Weaver in 1940, and the couple stayed married for 18 years with no kids. Once he began mingling among the cream of the crop, Cohen started feeling a little self-conscious about his illiteracy and his boorish behavior. Even though he remained ill-tempered and quick to fly off the handle his entire life, Cohen hired a private tutor to teach him better manners and basic schooling, so he could better fit in. He adapted well to the Hollywood lifestyle, especially as Siegel became more and more concerned with opening the Flamingo Casino in Las Vegas.

But 1947 proved to be a pivotal year for Mickey Cohen. Following years of poor management and skimming funds in Vegas, the Syndicate could no longer tolerate Siegel’s blunders. On June 20, 1947, Bugsy was shot dead in his Beverly Hills mansion, which immediately begged the question. Who would replace him as the new kingpin of Los Angeles?

War on the Sunset Strip

Once Siegel was out of the picture, it was business as usual for everyone else. Guys like Moe Sedway and Joseph Stacher took over his casino just hours after his murder, while Cohen received the go-ahead from the Syndicate to handle his businesses in Los Angeles. In his autobiography, Cohen admitted that, although he liked Bugsy, his assassination proved to be Mickey’s big break in the mob. Soon enough, Mickey Cohen was the new big boss of LA, and now he was the one meeting with Hollywood execs and partying with famous celebs. But his position was far from secure. Up until that point, Bugsy Siegel’s presence kept other rivals at bay, but his death showed that nobody was truly untouchable. Therefore, it wasn’t really a surprise when Jack Dragna decided that he wanted his spot at the head of the table back and that he was willing to go to war to get it.

Each man had his own advantages. Mickey Cohen was the one chosen by the Syndicate and he had the support of the Commission back in New York. But that was literally on the other side of the country and couldn’t be counted on all the time. Meanwhile, Dragna was still in good standing with the Chicago Outfit, but not good enough that they would be willing to go to war with New York for him. His biggest asset was his connections with the Los Angeles police since he had decades-old relationships with all the crooked cops in the city.

Remember when we said earlier that Mickey Cohen survived his first assassination attempt of many while working for the Capones in Chicago? Well, now it’s time for all the rest and, frankly, it is miraculous that Mickey Cohen ended up dying of natural causes. There were so many close calls that it showed that Cohen had Mr. Magoo-levels of good luck and that Jack Dragna strictly employed Stormtroopers with astigmatism as hired gunmen.

More details

ARRAIGNED—Mickey Cohen and some of his henchman in court yesterday as they appeared for arraignment. Front from left, Edward Herbert, Mickey Cohen, Frank Niccoli. Back, James Rist, Eli Lubin and Louis Schwartz. Credit: Los Angeles Times – https://digital.library.ucla.edu/catalog/ark:/21198/zz0017r8s7, CC BY 4.0

For example, one of the first attempts on Cohen’s life was an ambush while he was driving home. Even though several gunmen unloaded on his car with shotguns and Tommy guns, none of them hit anything. Cohen fell to the floor of his Cadillac and drove it blind down Wilshire Boulevard, and not only did he escape with just a few scrapes from broken glass, but he didn’t even hit anything. After this event, Cohen got himself a custom-made bulletproof Cadillac, fitted with eight-inch thick, armor-plated doors.

On a different occasion, Cohen was coming out of a joint and heading towards his car while, unbeknownst to him, a sniper was lining up his shot. Cohen stopped suddenly and bent down to inspect a scratch on the fender, at which point a bullet flew over his head and hit his precious Cadillac once again.

A different sharpshooter was more successful since he, at least, managed to injure Cohen by hitting him in the arm while the mob boss had lunch at a diner. Unfortunately, after the original shot didn’t take down its target, the sniper began unloading indiscriminately, injuring several innocent diners, as well as killing one of Cohen’s associates.

But, without a doubt, the most preposterous assassination attempts were the ones inside Cohen’s own home. First, Dragna managed to sneak a World War II Bangalore torpedo inside the house. It was a long and thin explosive used by combat engineers to clear obstacles but, on this particular occasion, the charge did not go off. Then, on another occasion, Dragna’s men planted an old-fashioned bomb underneath Cohen’s bedroom and, this time, it actually detonated. Just one problem, though – Cohen wasn’t in the bedroom. His alarm had gone off, telling him that there were intruders on his property, so he was sneaking around through the downstairs living room when the explosion went off. Cohen later observed that his neighbors got it worse than him since the concussion blast faced their house, but he also bemoaned that the explosion took out most of his expensive wardrobe.

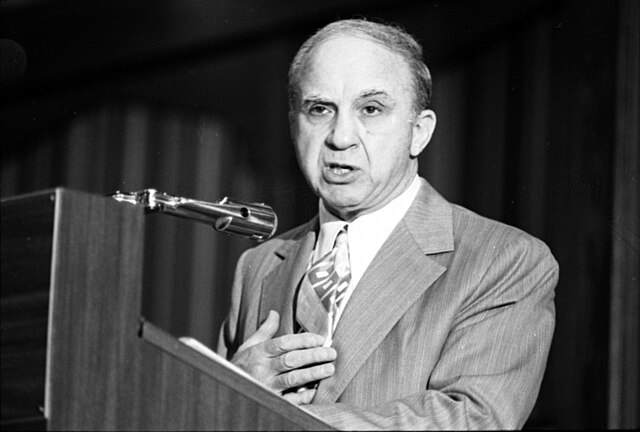

Still, this was the sixth attempt in four years and those are just the ones that made the press. And while Cohen himself kept surviving, the same could not be said for the people around him. Several henchmen either disappeared or were killed during these years, and even the mobster’s attorney was gunned down in front of his own home. There weren’t enough bribes in the world to hush up this kind of violence so in 1950, the US Senate formed a special committee to investigate organized crime. Many mob bosses, Cohen included, were called to testify in the Kefauver hearings, as they became known, and it was all televised, giving many Americans their first exposure to the world of the Mafia.

Mickey Cohen got off scot-free following the Kefauver hearings, but he was now firmly on the radar of the authorities and they began investigating him for all sorts of nasty business. Ultimately, they got him using the “old faithful” of mob convictions – tax evasion – and Mickey Cohen was sentenced to five years in prison.

The Undisputed Kingpin

Mickey Cohen was released from prison in late 1955 after he got nine months off for good behavior. During his time behind bars, Cohen generally kept a low profile, tried to avoid getting into trouble, and read a lot of books in an attempt to make up for his lack of a childhood education. That being said, once he was out, he was eager to re-enter LA’s underworld and reclaim his spot at the top of the food chain.

This was surprisingly easy to do. In the time he had been locked up, Los Angeles police cracked down on organized crime, so nobody was really able to take his place. Furthermore, Cohen received a wonderful present just a few months after his release when his archenemy, Jack Dragna, died of a heart attack. Therefore, Mickey encountered little resistance on his way back to the top and, in fact, he became even more of a public figure during his second stint as a mob boss. He developed strange and publicized friendships with evangelist Billy Graham and the Hearst publishing family, and he raised funds for several prominent politicians, but it was a bizarre feud with actress Lana Turner that garnered him the most attention in the press.

Lana Turner had been married to one of Cohen’s trusty sidekicks, a guy named Johnny Stompanato. But unsurprisingly, Stompanato was a violent, hot-tempered man who subjected Turner to frequent physical and mental abuse. One night in 1958, things got so bad that Lana’s 14-year-old daughter, Cheryl Crane, stepped in to protect her mother, and stabbed Stompanato to death. During a highly scandalous and publicized inquest, the death was ruled justifiable homicide, so both Lana and Cheryl were off the hook. Cohen, however, didn’t like how his friend had been portrayed by the media so he went on a smearing campaign against Turner. He released private letters between Lana and Johnny and was one of the main people who forwarded the conspiracy theory that somebody else actually killed Stompanato that night and that the daughter took the blame so they would get away with it.

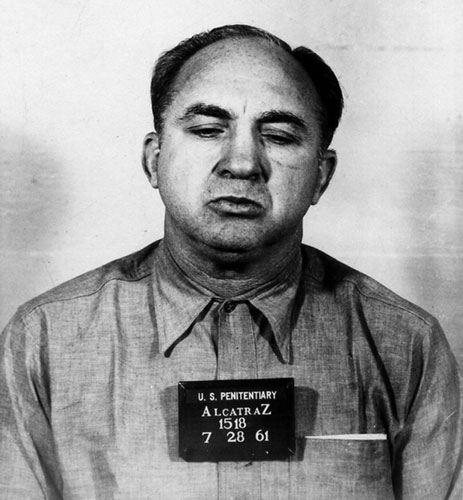

Unfortunately for Cohen, his time back as the boss ended abruptly because, in 1961, he was found guilty of tax evasion again and sentenced to another 15 years. He was sent to the notorious Alcatraz but only spent a short while there before being released on bail while his appeal was pending. The appeal failed in 1963, but by then Alcatraz had closed down as a prison and became a museum, so Cohen was sent to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta.

That was Cohen’s life for the next decade. Early on into his sentence, he survived one final assassination attempt when another inmate named Burl Estes McDonald bludgeoned him with an iron pipe and cracked his skull, causing Cohen to get a steel plate fitted inside his head. The attack left the once-mighty mob boss permanently disabled and he needed a cane to move around from then on.

Cohen was released from prison in 1972, once again getting time off for good behavior and because he was suffering from stomach cancer which had been originally misdiagnosed as an ulcer. It would be fair to say that this was somewhat of a “farewell tour” for Cohen, who knew he didn’t have long left. Gone were the days when he was brushing off attempts on his life in the pursuit of power and wealth. Now, he was more interested in meeting old friends, catching a boxing match, and generally keeping a low profile. He actually made several television appearances, advocating against prison abuse.

Mickey Cohen had one final and bizarre brush with fame in 1974 when he got involved in the infamous Patty Hearst case when she was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army and eventually joined her abductors. Cohen claimed to have connections to the SLA and that he could attempt to negotiate Patty’s release, but his offer was refused by the Hearst family when it became clear that Patty had joined the SLA and that she risked prison.

Mickey Cohen died on July 29, 1976, aged 62, of complications from stomach cancer surgery. He reigned at the top of Los Angeles’s underworld, he survived 11 assassination attempts (according to him), and even enjoyed a few years of peace and quiet following his release from prison, and that was a lot more than what most of his associates got.