“All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible. This I did.”

When the life story of British Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence made it to the silver screen in 1962, under the direction of David Lean, starring Peter O’Toole as the main character, it was hailed as one of the greatest movies ever made, a prestigious reputation which it still holds to this day.

But what about the real person behind the movie? Today we explore the story of the man who went to war and became known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Early Years

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born on August 16, 1888, in the village of Tremadog, in north Wales. He was the second son of Sir Thomas Chapman, 7th Baronet, and was born out of wedlock after his father left his wife and four daughters and ran away with the governess, Sarah Junner. When Sarah became pregnant, the couple fled Ireland, where Chapman lived with his first family, and relocated to Wales, where they adopted the surname Lawrence and soon gave birth to their first son. Afterward came Thomas (or Ned as the family called him), followed by three other sons, although the couple never married because Chapman never attempted to divorce his wife.

Young Ned lived a nomadic lifestyle for most of his early childhood, as the family moved around from place to place until 1896 when they finally settled in Oxford. That was where he went to school and also attended an Anglican youth organization called the Church Lads’ Brigade, at the insistence of his devout mother. She hoped that her sons would follow some kind of holy calling in life, but this didn’t really jive with Ned’s budding thirst for learning and adventure.

Tensions between mother and son steadily rose as the years went on. Sometime during his childhood, Ned found out about his parents’ sordid past, and that he and his four brothers were all illegitimate, but he never attempted to confront his parents over it or make contact with his step-siblings. Lawrence claimed that his relationship with his mother was at its worst in 1905 when he ran away from home and enlisted as a boy soldier in the army until his father showed up and bought him out of service. However, historians have not been able to find any records of this happening, so either the army wasn’t very thorough when it came to keeping tabs on new recruits, or Lawrence was prone to exaggeration. As you will soon find out, this wasn’t Lawrence’s only claim that has been brought under scrutiny.

Either way, Ned found himself back home again, but he gained a modicum of independence when his parents agreed to build him a bungalow at the end of the garden, where he had some privacy and was free to pursue his true interests. It soon became pretty evident that the church was not one of them. Instead, he developed a taste for studying the past, but he preferred to get his dose of history al fresco, going out in the field instead of sticking his nose in dusty, old books. He became a keen cyclist, who liked to travel to castles and churches all over the country to take photographs and brass rubbings.

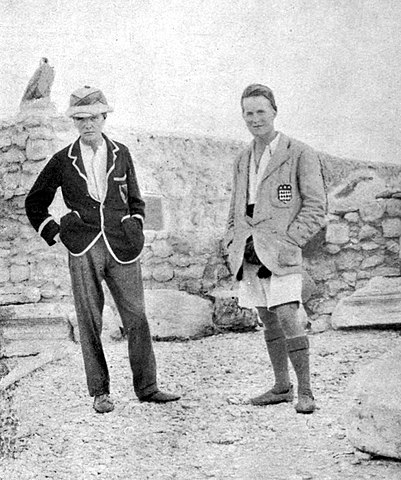

He took up cycling partly as a way of making up for his small stature. Unlike the lofty physique of actor Peter O’Toole, the real Lawrence was only 5’5″ tall and had quite a big head for his size. He felt pretty self-conscious about this his entire life, which is why he was always looking to build up his strength in order to compensate. Another way he kept fit was by avoiding all alcohol, tobacco, and meat, though he occasionally indulged in them whenever he wanted to abide by local customs.

When Ned ran out of castles to study in Britain, he traveled to France for two summers in order to see what they had to offer. In the summer of 1909, the 20-year-old Lawrence embarked on his most ambitious adventure yet – he went on a walking tour of the crusader castles in Syria which, back then, were mostly part of the Ottoman Empire. He walked over 1,600 kilometers during a three-month period, receiving firsthand exposure to the Arabic culture that would define his entire legacy.

Archaeology & War

When Lawrence wasn’t bicycling his way from castle to castle, he was studying medieval history at Jesus College, Oxford. He used the material and information he obtained in Ottoman Syria to write his thesis and he graduated with first-class honors in 1910. Now that he was finished with school, Lawrence needed a career. Ideally, something that combined historical studies with the exploration of landmarks in far-away locations. The choice seemed obvious. With his parents’ full support, Lawrence became a quantity surveyor… Just kidding, he became an archaeologist.

In 1911, he already had his first gig lined up, thanks to his mentor, British scholar David George Hogarth. As an established archaeologist, Hogarth was in charge of an expedition to Carchemish, set up by the British Museum, and he took Lawrence along for the ride. Located today on the border between Syria and Turkey, Carchemish was once an ancient settlement that acted both as an independent city-state and an important part of the Hittite Empire. Hogarth and his team spent the next three years excavating in the region, allowing Lawrence to witness firsthand the struggles present in the region. He formed a close friendship with a young Arab water boy named Dahoum, who then served as his assistant and traveling companion. Somewhat fittingly, his team’s biggest rival in the area wasn’t any of the locals, but the Germans, who were there building a railroad and kept butting heads with the English over land access.

At the start of 1914, tensions between nations were at an all-time high, as war loomed over the world. Lawrence was given a new assignment to explore the Negev Desert. Ostensibly, he was doing this at the behest of a British archaeological society called the Palestine Exploration Fund, trying to find a biblical location named the Wilderness of Zin. In reality, though, this was basically a spy mission, as the project was a smokescreen staged by the British military to allow Lawrence and his team to survey the Negev Desert and map out important features such as safe routes, water sources, etc. This information was considered of great strategic importance should war break out.

And, of course, as we all know, war did break out. Lawrence was back in England at the start of the First World War. He was keen to join in, but wasn’t sure where exactly his talents would best be employed. His uncertainty was resolved in the fall of 1914 when two important things happened. One – the Ottoman Empire officially joined the war; and two – Britain deposed the Egyptian leader Abbas II due to his Ottoman sympathies and declared Egypt a British protectorate. Shortly thereafter, Lawrence was summoned to work for a newly-formed intelligence unit headquartered in Cairo named the Arab Bureau.

As it turned out, Lawrence was good at his new job. He understood the history and the problems of the Arabs, he spoke their language fluently, and, most of all, he had a genuine interest in their fate. In his mind, the ideal outcome would have been for the Arab people to gain a true independence that allowed them to retain their identity and their culture. This wasn’t necessarily the vision shared by the British government, which was mainly looking after its own interests, but it wasn’t completely against it, either. Obviously, the worst-case scenario was for the Ottoman Empire to retain its hold over the Arab people and maintain its dominion in the region. Another unfavorable outcome, as far as the British officers at the Arab Bureau were concerned, was for France to gain concessions in the area following a victory in the war. Sure, France was their ally, but the feud between the two nations was a rivalry as old as time, so while they needed France to win, they didn’t want it to win…too much. Of course, Lawrence had no idea at the time that Britain and France were already discussing a secret treaty known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement to divide their spheres of influence in the region after the war. Therefore, Lawrence and his colleagues were busy dealing with intelligence and propaganda against their own ally in order to, in his own words, “biff the French out of all hope of Syria.”

The biggest downside to Lawrence’s job was that it was done mainly behind a desk. Sure, he had no military training, but he was still eager to get out there and see some action. Some have speculated that he felt survivor’s guilt because he had a safe, cushy job during the war, while two of his brothers died in 1915 fighting on the Western Front, which was why he acted so reckless once he was actually out in the field. True or not, Lawrence would soon get his wish. He might have spent all of 1915 as a pencil pusher, but the following year would take a drastic turn.

Lawrence of Arabia Is Born

In June 1916, the Great Arab Revolt started – a military uprising of the Arab forces united against their common enemy, the Ottoman Empire. The leader of this army was Hussein bin Ali, a member of the Hashemite royal family and the Grand Sharif of Mecca, as well as the king of the newly self-proclaimed Hashemite Kingdom of Hejaz. The British government played an important role, as it not only promised to supply the Arabs with weapons but also to recognize the single unified Arab state that would emerge if they defeated the Ottoman Empire. With that much skin in the game, the British were not just going to sit back and hope for the best. They wanted their own men to work closely with the Arab forces.

That’s where T. E. Lawrence came in. By October of that year, the Sharifian Army of King Hussein had achieved some initial success, but their resolve and morale had begun to falter as the enemy still had the strategic, numeric, and military superiority. Lawrence was sent in on a fact-finding mission to gather intelligence about how the war effort was going and, from this point on, you know most of what happens if you’ve seen the movie. First, he met with all of King Hussein’s sons. The sharif was already in his 60s by that point, so he wasn’t going to be the one leading boots on the ground. Lawrence concluded that Prince Faisal would be the one best suited to lead the revolt.

Following their little tête-à-tête, Lawrence sent a glowing report back to headquarters, which not only commended the efforts of the Arab army, but also discouraged the need for British troops. This might have not been entirely accurate, but it was music to the ears of his superiors, who wanted those soldiers for other frontlines, and, consequently, Faisal asked for Lawrence to be assigned to him permanently as a liaison officer – a request which was granted and, thus, Lawrence of Arabia was born.

Lawrence advised Faisal to delay his attempts to capture Medina in favor of strengthening Arab-controlled cities such as Yanbu and Jeddah, while at the same time carrying out regular raids on the Hejaz railway that traveled from Damascus to Medina in order to disturb Turkish supply lines. Strategically, it was sound, but not exactly thrilling. How about a new plan with some chest hair? A plan that was dangerous and reckless, not to mention that it went against the wishes of the British government? A plan such as, I don’t know, leading an assault on Aqaba?

The Battle of Aqaba

Again, if you’ve seen the movie, this is like the first half of it, and that thing’s almost 4 hours long, so suffice to say that it was a crucial turning point not just for Lawrence’s legacy, but also for the Arab Revolt. In case you need a quick refresher, Aqaba was a coastal city located at the very northern tip of the Red Sea, nowadays situated in Jordan. It had great strategic value because it was surrounded by mountains on two sides and could have been used as a naval base for German submarines and minelayers in the Red Sea. Taking it from the front was almost impossible because the city was protected by a narrow gorge that would have funneled enemy ships into cannon range like lambs to the slaughter. The eastern flank, however, was not very well protected, mainly because the Turks were not expecting anyone to attack from that direction.

Lawrence thought that taking Aqaba would have been of great importance for his side, but especially for the Arabs, who would then be able to use it as a base for conducting raids on the Damascus-Medina railway. He actually went against his superiors to get this done. Of course, the British would have liked the city to be in friendly hands, but they kinda sorta promised it to the French, plus that they did not think that a small group of underequipped Arab fighters would be able to occupy the port.

And they probably would have been right, if not for one man – Auda Abu Tayeh. He was the leader of the Howeitat tribe and described by Lawrence as the “greatest fighting man in northern Arabia.” While Feisal might have been the spiritual leader who inspired the Arabs, Auda was the warrior general who fought alongside them and led them to victory. He was described as modest, honest, and kind-hearted to his guests, but a wild beast to his enemies. According to legend, Auda killed 75 Arabs by his own hand, and he never bothered to count the Turks because those would have been in the hundreds.

The Howeitat were regarded as the finest warriors in the desert, so it’s no surprise that both sides wanted them as allies and not enemies. At the start of the revolt, the Howeitat were, technically, on the payroll of the Ottoman Empire, but they weren’t on friendly terms, by any stretch of the imagination. But just like with Feisal, Lawrence both charmed and inspired Auda to fight for the Arab cause. And once Auda was in, he was in all the way, becoming the main military leader of the revolt and turning down multiple offers from the Turks to switch allegiances once more.

Unlike the movie, the real Arab force never crossed the impassable Nefud Desert in order to reach Aqaba for a simple reason – there was no need. That was just a bit of movie magic to add more drama. In reality, the army stayed on the road, by the edge of the desert, attacking several Turkish garrisons along the way.

When Lawrence first set off on this 1000-kilometer, two-month-long camel trek, he was accompanied by just 45 men. By the time he reached Aqaba in July 1917, that number swelled to at least 500, and maybe up to thousands, depending on who you ask. Many Arabs were ready to fight for the cause, especially when it was supported by key figures like Feisal and Auda.

Calling this the Battle of Aqaba is a bit disingenuous because the real fighting actually happened at Aba el Lissan, about 65 kilometers away, where the bulk of the Turkish forces was located. On July 1, the Arab army took them by surprise and decimated the enemy, killing around 300 soldiers and taking another 300 prisoners, while they only sustained two casualties. Afterward, when the Arabs stormed the city of Aqaba, the few soldiers still stationed there only fired a few shots before officially surrendering on July 6.

It was a huge victory for the revolt and for Lawrence, personally, but we should remember that he was still an amateur archeologist with no military training. He was merely roleplaying as a soldier and somehow had not gotten himself killed yet thanks to buffs in luck and charisma. Here’s a perfect example of that – during the battle, Lawrence did not take part in the initial charge. Why? Because he was thrown off his camel right as the fighting started. This alone was embarrassing enough, but when Lawrence got up, he noticed that the reason why he was thrown off was that, in all the excitement, he had accidentally shot the animal in the back of the head.

Life after the War

Following the success at Aqaba, the fact that Lawrence went against his orders was conveniently forgotten. His new boss, General Edmund Allenby, was a fan of Lawrence’s derring-do. Allenby had just been transferred from the French frontlines and, by comparison, the war in the Middle East was a lot more boring (for the British, at least). Therefore, he was inclined to grant several of Lawrence’s requests to help the Arab Revolt.

The most controversial aspect of Lawrence’s life happened soon after, on November 20, 1917, when he was captured by Turkish guards while in Daraa in disguise, and subjected to beatings, torture, and rape. Initially, scholars thought that this had a great psychological effect on Lawrence’s behavior, and made him more reckless and bloodthirsty, but nowadays some have gone the other way and claimed that the officer exaggerated the event in his book, and some even accused him of making the whole thing up.

Whether or not it happened, in the short term, Lawrence did not allow the traumatic event to get in the way of his plans. He continued to go on recon missions in disguise and he continued to lead raids on the railway. But these were mere distractions. As the strength of the Allied Powers kept growing, already he saw Britain and France making plans to divvy up the region after the war, plans that only tangentially included the local forces. He thought there was one more hope for the Arab people – if they controlled one of the major cities when it was all said and done, they would have a good bargaining chip during negotiations. He wanted them to take Damascus.

Unfortunately, things didn’t go exactly according to plan. Damascus did fall on October 1, 1918, and Lawrence entered the city triumphantly in a Rolls Royce. However, when he did so, he was greeted by Allied units who were already inside because it was the Australians who first captured the city, not the Arabs.

Pretty much what Lawrence expected to happen, happened. A lot of bureaucratic brouhaha between the various sides over who was in charge. The Arabs tried setting up a government but were forced by the Allies to accept French supervision. Meanwhile, Lawrence’s pleas fell on deaf ears, and when his superiors finally got tired of him, they promoted him to colonel and sent him back home to England. And, just like that, Lawrence of Arabia was gone.

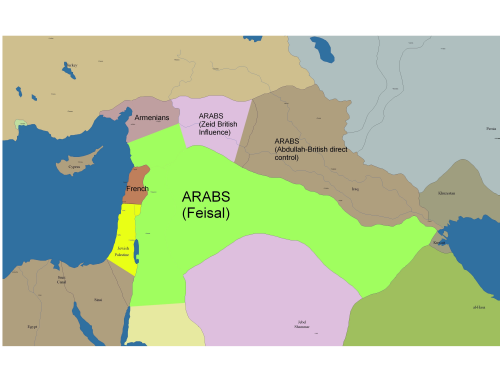

Once the war was over and Allied forces left the Middle East, Faisal tried proclaiming himself king of the new Arab Kingdom of Syria, but none of the Allied Powers recognized his authority. Instead, following the San Remo Conference in 1920, they awarded the mandate of Syria to France. This led to the brief Franco-Syrian War, which didn’t actually involve Faisal himself, as he willingly surrendered, but one of his ministers who wasn’t quite ready to throw in the towel. France easily won, dethroned Feisal, and established the French Mandate of Syria. Meanwhile, as a sort of consolation prize, the British made Feisal the King of Iraq, a position he held until his death in 1933.

Back in England, Lawrence got to work on writing his book, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, about his experience during the Arab Revolt. He finished it in 1922, but it wasn’t published until 1926. He often expressed his shame at what he saw as a betrayal of the Arab people, and considered himself partly responsible for wearing a “mantle of fraud” throughout the military campaign for giving them hope when he knew the true intentions of his government. He kept trying to advocate on behalf of the Arab people for years after the war, working as a diplomat and advisor for Winston Churchill.

Lawrence experienced newfound fame during these years. During the war, his exploits had been kept strictly hush-hush, but now everything was out in the open. It was actually an American writer and broadcaster named Lowell Thomas who popularized his adventures and turned him into a household name.

Lawrence wasn’t too fond of being a celebrity, though. Once he finished writing his book, he tried joining the Royal Air Force under the assumed name of John Hume Ross. When he was discovered, he was discharged, but then enlisted in the tank corps, under yet another name, T. E. Shaw. After a few years, he was allowed to transfer back to the RAF, where he remained until shortly before his death. He was a fan of all high-speed machines – airplanes, motorcycles, powerboats, and worked on them all as an aircraftman and mechanic.

Lawrence had his own Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle which he dubbed “George V.” On May 13, 1935, he was riding his beloved George through Dorset, when he swerved suddenly to avoid two boys on bicycles. He lost control of the motorcycle and crashed. He died of head injuries six days later, on May 19, aged 46.

Lawrence had one last inadvertent effect on the world. One of the doctors who attended to him after the accident was an Australian man named Hugh Cairns, who went on to become a pioneering neurosurgeon. Following Lawrence’s death, Cairns was inspired to study head trauma on motorcycle accident victims, and his research led to the adoption of crash helmets.