In the early 1860s, the Territory of Colorado would have been the perfect setting for a classic Western movie.

Mexican farmers uneasily cohabited with recently arrived American settlers and gold prospectors. The Union cavalry and US Marshals patrolled the canyons, woodlands, and gulches, searching for bandits, skirmishing with the Native nations, or recruiting volunteers for the ongoing Civil War in the East.

But from Spring to Autumn 1863, these lawmen would be confronted with a whole new breed of horror, one we would normally associate with another genre altogether.

The Territory’s settlers faced three seasons of terror due to the murderous insanity of the ‘Axe man of Colorado’: Felipe Espinosa.

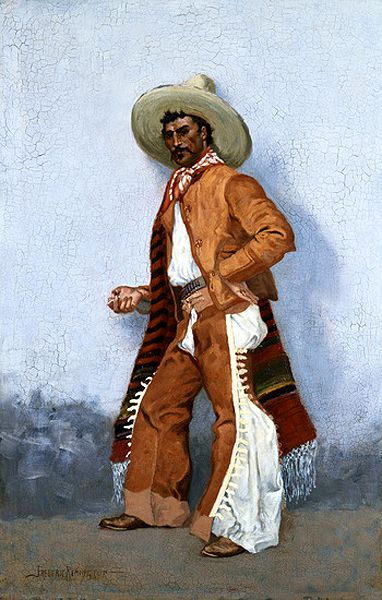

Described at the time as a Mexican bandit, he achieved infamy as one of the first – if not THE first – serial killers of the Wild West.

Los Hermanos Penitentes (The Penitent Brothers)

Felipe Nerio Espinosa was born in 1827, in what is today known as the El Rito unincorporated community, Rio Arriba County, New Mexico.

He was the older of five siblings. One of them, Vivián, born in 1831, would become a trusted partner in crime.

There is only sparse information about the early lives of Felipe and Vivián. What we know is that their parents were subsistence farmers of meagre means. Literacy was not a given amongst these rural communities, yet at least Felipe and Vivián could read and write.

Felipe was known amongst neighbors for his impulsive, volatile, and violent temper. This worsened after the Mexican American War of 1846 to 48. After the war, the United States acquired large swathes of territories from Mexico – including the lands where the Espinosas had settled.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo allowed Mexican residents to remain in the newly ceded lands, but Washington also encouraged settlers to travel West and start farming the same territories!

Inevitably, simmering tension and open conflict manifested between the two communities, known as ‘Hispanos’ and ‘Anglos’.

As a proud Hispano, Felipe resented the Anglo newcomers.

He saw them as usurpers, oppressors, and enemies of the true Catholic faith. Both Espinosa brothers were indeed devoutly religious and were members of the Holy Brotherhood of the Blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Members of this Fraternity were also known as ‘penitentes’ and provided philanthropic help to the less fortunate. However, some of their numbers also indulged in extreme religious practices such as self-flagellation.

It is not clear if Felipe inflicted such violence upon himself.

But it appears that he did inflict it upon others.

In 1854, Espinosa decided he wanted to marry. But as he had no luck with the local ladies, he traveled south to the village of Cochití and abducted two sisters, Secundina and Eugenia, aged 17 and 11 respectively.

Thankfully, he almost immediately set free Eugenia, but he kept the older sister with him for several days, mentally and physically abusing her.

Secundina finally escaped and returned to her family, quickly chased by Felipe.

But her father, terrified by Espinosa’s violent character, convinced the girl to marry her abductor.

We don’t know if their relationship developed into less toxic patterns. But we know for sure that they went on to have three children.

In 1858, the Espinosa extended family moved from El Rito to the San Luís Valley, Southern Colorado. The Espinosas settled into a plaza, or community of small farmhouses. According to different sources, this plaza was either known as San Rafael, or San Judas – we will go with Judas.

By April, 1861, the American Civil War had erupted. Colorado was not yet a State, rather a Territory, and the ravages of war had not reached the San Luís Valley.

According to a census of that time, Felipe and little brother Vivián were making a living as a brick maker and farmer, respectively. Yet, around this time, it appears that the two brothers took to banditry.

It is unclear who was the bad influence, or exactly what were their crimes. Possibly cattle-rustling. But it seems that they earned a reputation in the press as “desperate and lawless bravos.”

Calvario en San Judas (Calvary in San Judas)

For much of 1862, the Espinosas were occasional bandits. Amateurs if you like. But their criminal career was to take a sharp turn in December.

Around that time, a priest from the town of Taos reported a gruesome robbery to the US cavalry stationed in Fort Garland.

Two masked men had held up a wagon carrying some of the priest’s properties. The bandits looted the vehicle, then seized the driver, Juan Gonzalez. They tied the poor man underneath the wagon and then whipped the horses, sending them galloping across the rocky soil. The driver’s head and face hit every bump and stone on the path, turning into a bloody pulp.

Luckily, he survived and was able to identify the culprits: the Espinosa brothers of San Judas plaza!

Cavalry Lieutenant Hodt organized an expedition in mid-January 1863, accompanied by ten horsemen and a US Marshal, George Austin.

The lawmen paid two visits to Felipe Espinosa’s farmhouse.

The first time, they pretended to be on a recruitment mission. Most of the cavalrymen were Hispanos after all. Why not enlist with them, and then join the Union Army in the Civil War?

Vivián talked to the Lieutenant quite civilly, apparently. It is not clear why Hodt did not arrest him and Felipe there and then.

Instead, the detachment left and returned five days later. This time, Hodt and Austin went straight for the arrest, locking Felipe and Vivián into their house.

But then all chaos erupted.

Apparently the Espinosas had access to a veritable arsenal, which nobody had cared to confiscate. The two brothers started firing from the windows with pistols, rifles, even bows and arrows.

The cavalry shot back with little success, until Hodt ordered for the house to be set on fire. At that point, Felipe and Vivián made a desperate sortie, discharging more arrows.

The lieutenant drew his pistol and fired all his rounds – missing every single time.

His second pistol didn’t seem to work, so he threw it to the ground in frustration.

And that’s when it decided to work!

A bullet went off at that moment, wounding Hodt on the forehead.

In the meanwhile, the Espinosas were running away, across the frozen River Conejos. Marshall Austin gave chase, but his horse slipped on the ice. Man and beast both crashed to the ground.

The whole expedition had been a disaster. The two bandit brothers had disappeared into the San Juan Mountains. The Marshal had a broken leg; the lieutenant had almost shot himself in the brain; and sadly, a corporal had been killed in the hail of gunfire.

The Army reacted harshly to the debacle. They completely burned down the Espinosa farmhouse and confiscated all their belongings, including their livestock. The entire extended clan was left destitute as a result.

This incident may be at the root of the darkness that descended on Colorado – the killing rage of the Espinosa brothers.

Un Banquete para los Buitres (A Feast for Vultures)

Felipe and Vivián stole two horses during their retreat and made the mountains their new home, on the run from the law. According to later lore, it was during one of the freezing nights camping in the woods that Felipe had a vision, a revelation.

The Virgin Mary appeared in his dreams. Sent as a messenger from God, the Virgin had ordered Felipe to kill and kill again, until the blood of 600 Anglos had been spilt.

According to Felipe’s own later writings, he had lost six relatives during the Mexican American war. And he would wash that trespass in blood, of course, killing 100 Anglos for each Espinosa.

Whatever the motivation, the Espinosas were hell bent on going on a killing spree. Their hunting ground initially was an area called Sawmill Gulch, just outside Canyon city. It later became known as ‘Dead Man’s Gulch’.

Their first victim was sawmill worker Franklin Bruce, shot on March 16, 1863. According to some newspaper reports a crucifix made of sticks protruded from his bullet wound.

Two days later, it was lumberjack Henry Harkens’ turn. His co-workers found him one evening, laying inside his cabin.

He had been shot in the forehead with a ‘Colt Navy ‘revolver. He also had two stab wounds on the chest.

The most gruesome detail is that the murderers had split his head in half with an axe. They had inflicted further blows to his skull, scattering fragments of bone and brain matter all over the floor. In a matter of days, the third victim was found: James Addleman, killed near Wilkerson Pass, west of Colorado Springs.

During April, the ‘Bloody Espinosas’ targeted the town of Fairplay.

Jacob Binkley and Abraham Shoup were taken by surprise as they camped outside the city limits.

Binkley was shot in the back and died on the spot.

Shoup was stabbed three times and tried to escape, but collapsed after a short run.

Three more men were slain at the end of the month. One had been shot, another one’s head was crushed under a rock. A third one had died with a bloody crucifix carved onto his chest.

At the time, lawmen had not yet connected these deaths with the two bandidos from San Judas. They believed the culprit to be a lone wolf, dubbed by the press “The Axeman of Colorado.”

The dwellers of the Territory were gripped by fear and suspicion. Any stranger wandering into town could be the dreaded killer. An unlucky prospector, Mr Foster, arrived in the town of Alma at the wrong time. He was suspected of being the axeman and beset by a vigilante mob. The townsfolk dragged him to a tree for hanging.

He was saved at the last minute by the oratory prowess of a minister, who subdued the crowd.

The Governor of the Territory, John Evans, offered a bounty for the capture of the Axeman. He also appointed Colonel John Chivington to lead an infantry detachment to search the region. One of the officers involved was Lieutenant Shoup, brother to one of the Fairplay victims.

He offered to double the bounty out of his own pocket, but the Axeman – or I should say, the Axemen – remained elusive.

It was later rumoured that they were helped by other ‘brothers’ of the Penitente fraternity. But it is more realistic that they simply moved very quickly along mountain paths, preying on lone travellers.

As they added more victims to their tally, the spree killers refined their modus operandi.

In this second phase of their descent into madness, they ditched the Colt for long-range rifles. After stalking their prey, they cut them down from afar. Then, they descended upon the corpses like vultures and they set to work.

Bodies were found disemboweled, decapitated, their hearts brutally removed or impaled by wooden stakes.

However ghoulish, the two murderers were all too human, and sooner or later they would commit a mistake.

La Muerte de un Hermano (Death of a Brother)

A lumberjack called Matthew Metcalfe was driving a wagon down California Gulch, when the Espinosas suddenly appeared in front of him. Without saying a word, one of them fired a shot, hitting Metcalfe on the left breast. The lumberman fell backwards into the wagon, as the panicked horses dashed wildly away.

Felipe Espinosa later wrote in his diary “killed a man in a wagon.”

But he hadn’t.

Matthew had been saved by a booklet of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, stuffed into his breast pocket. The pages had slowed down the flight of the bullet, saving Metcalfe’s life.

Finally there was a survivor, someone who could help describe and locate the scourges of Colorado.

Metcalfe reported the botched shooting and a posse of eight men was quickly formed in Fairplay, led by John McCannon. The posse found a promising trail of hoofprints close to California Gulch. Following the path, the horsemen found a gruesome clue: a corpse, butchered beyond recognition.

Well, almost.

One member of the posse recognised the body. It belonged to his brother!

McCannon and his men continued riding for one day and one night. After daybreak, they saw two horses, calmly grazing behind a screen of campfire smoke.

The posse split into two groups and approached the camp site.

They crept through the grass, fingers nervously twitching by the trigger of their guns.

When a human figure emerged from a bush, the men of Fairplay reacted quickly, too quickly perhaps.

Without any warning, a shot rang out.

A red stain bloomed on the man’s side, as he slumped to the ground.

It could have been any innocent traveller. But in this case, he wasn’t.

Vivián Espinosa cried out in fury and returned fire with his Colt. More rounds came flying to his direction, until one tore through his brain. A second figure came running from behind the trees. McCannon shouted to hold fire, believing him to be a member of his posse.

This was Felipe of course. Taking advantage of the moment of confusion, he sprinted away, before the Fairplay gunmen could take aim.

Espinosa disappeared into the woods, pursued by those who had killed his brother. He managed to evade capture until sundown, when the posse returned to the encampment.

The now lone Axe man followed them stealthily and shot one last time, before disappearing for good. The bullet missed the man who had killed Vivián by a mere three inches.

McCannon and his men returned to Fairplay with a valuable load: all the loot that the Espinosas had stolen from their victims, and Felipe’s own diary.

Based on the property seized, Fairplay authorities concluded that the outlaws had killed at least 12 men. But in Felipe’s diary, they found an unsent letter to the Colorado Governor, in which he confessed to 32 murders.

El Fin se Acerca (The End Draws Near)

With Vivián dead and Felipe once more on the run, Colorado breathed a sigh of relief. The summer was relatively calm; no more Anglos were felled by the axe of the Hispano. The Army and posses of settlers still roamed the woods and mountains, but Felipe managed to elude them. He even returned several times to his family’s dwelling, San Judas Plaza.

When visiting, he dropped further letters and portions of his diaries, confessing to the string of murders, and threatening further violence. He also took notice of his family’s condition: following the cavalry raid in January, the Espinosas had fallen into abject poverty.

It was during one of these visits that Felipe recruited a new accomplice: a nephew, of which little is known. He may have been 14 and his name could have been José, Julio, or Julian. We will go for Julio.

It is not even clear why he recruited the boy. Was he looking to initiate a new generation of Espinosas to anti-Anglo violence? Or maybe he just needed somebody to look after the horses and the campfire.

Whatever Julio’s age or function, Felipe returned to his murderous ways.

In Autumn of 1863, as the leaves started to fall, so too did the bodies.

In a matter of a few weeks, at least eleven killings were recorded in southern and central Colorado, attributed to Espinosa.

On the 11th of October, 1863, Felipe and Julio had set up an ambush at La Veta Pass.

As a wagon approached, Felipe attacked, guns in hand. The wagon occupants, a man and a woman, fled on foot, in opposite directions.

The Espinosas ran after the man, called Philbrook, but soon lost track of him on the mountainside. They returned to La Veta, looking for the woman, Dolores Sanchez.

Meanwhile, she had hidden aboard another wagon, driven by two Hispanos.

Felipe and Julio held up that wagon as well, and upon finding that the drivers were Mexican, seemed eager to let them go unharmed. Dolores could have made it unscathed, too, had she not emerged from her hiding, pleading for the drivers’ lives.

Her generosity of spirit would not be rewarded, alas. Felipe allowed for the two Hispano drivers to trot away, but would not reserve the same favour to this Hispano lady.

With Julio’s help, Felipe bound her tightly, and then proceeded to rape her.

The Espinosas abandoned her on the mountainside, as they galloped towards more mayhem.

But help was on its way. Philbrook had reached Fort Garland and alerted its commander, Colonel Tappan, to the situation. Tappan dispatched a patrol, who found Dolores in a bad shape, but still alive.

Back at the Fort, Dolores and Philbrook were able to give a detailed description of Felipe. Tappan was ready to strike back, but he would not lead the expedition.

He knew just the right man who could locate the Espinosas and deal the final blow.

Bring Me the Head of Felipe Espinosa

That man was Thomas Tate Tobin, a well-known tracker, trapper, and US Army scout, who had fought alongside Wild Bill Hickock and Kit Carson in the wars against the Native Americans.

Tappan summoned Tobin to the Fort, where he had the opportunity to further question Philbrook and Dolores. With all the info he needed, the scout reared to start the hunt immediately, alone! Only upon Tappan’s insistence did he accept an escort of 15 cavalrymen.

With his uncanny tracking skills, Tobin followed the trail of the Espinosas for three days and three nights. Every broken stick, every bent blade of grass on the ground, spoke clearly to Tobin, telling him where the bandits were headed.

On the morning of the fourth day, the scout saw magpies flying in circles in the distance. An indication of human presence. This was confirmed by a thin column of smoke, lazily rising above the treetops.

Tobin ordered the soldiers to stay put, loaded his rifle, dropped to his stomach and crawled towards the campsite.

Two men sat by the fire with a dead ox beside them. The tracker recognised them from the description he had heard at the Fort. It was the Espinosas.

A snapping sound reverberated through the forest, maybe a breaking branch. It was enough to startle Felipe, who reached for his rifle. Tobin reacted on instinct, barely taking aim; he released a slug, hitting Felipe on the chest.

The killer fell backwards onto the campfire, calling for Julio to run away. The young nephew sped through the woods, a swift shadow appearing and disappearing amongst the trees.

Now, Tobin took the time to perfectly adjust his aim. He squeezed the trigger a second time, and Julio’s spine was shattered by hot lead.

But Felipe was still alive. He crawled across the forest floor and braced himself against a tree. He lifted his rifle and shot against Tobin, but missed. The Union cavalry men now intervened, releasing a devastating volley.

Felipe Espinosa, the Axe Man sent by the Virgin to slay the Anglos, writhed and jerked against the tree bark, as bullet after bullet drained every drop of life from his body.

But when he fell to the ground, apparently, he still had one ounce of life left inside him. Tobin walked slowly to him and lifted him by the hair.

As he pulled out his bowie knife, Tobin asked him “Do you know who I am?”

With his last breath, Felipe muttered “Bruto.” A brute.

Then the ‘brute’s’ blade fell twice upon the neck of Espinosa.

Days later, Tobin returned to Fort Garland. As he strode into the office of Colonel Tappan he announced, “Got them.”

Tappan asked, “Got what?”

Tobin opened the flour sack he had been carrying, and pulled out the heads of Felipe and Julio.

And thus ends the narrative of Felipe, Vivián, and Julio, the ‘bloody Espinosas’ who may have been the first documented serial killers in the history of the Wild West. The events grew to acquire legendary status, perpetuated by one macabre relic: Felipe’s head, preserved in a jar of alcohol, was exhibited as a traveling act, before ending on the desk of a newspaper editor.

Then, the head disappeared, as the memory of the Espinosas largely faded from history.

According to author Adam Jones, a preserved head, which may have been his, was found in the early 2010s in the basement of Colorado’s Capitol building. It was incinerated before it could be analysed.

To this day, many details concerning the Espinosa’s killings and their eventual demise are still disputed.

Even the motivations behind their spree are not entirely clear.

Was Felipe really driven to kill by delirious dreams and visions of the Virgin Mary?

Or was the violence political in nature, a revengeful rampage against the Anglo oppressor?

Was he just a vile psychopath who had strung along his younger brother and a teenage nephew?

Or was he an insurgent, fighting with the wrong methods the just cause of Hispano freedom against oppression?

Perhaps Felipe’s rage was fuelled by all these elements, and the raid on his plaza was just the last straw that had tipped him over the edge of darkness.

SOURCES

‘Season of Terror: The Espinosas in Central Colorado’, by Charles Price, ISBN 978-1-60732237-5

https://adamjamesjones.com/2010/12/14/the-real-story/

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/outlaw-espinosagang/

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/felipe-espinosa/

https://www.5280.com/2019/12/the-long-forgotten-vigilante-murders-of-the-san-luis-valley/

https://www.historynet.com/vengeance-plain-madness-felipe-espinosa-led-murder-spree.htm

https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/bloody-espinosas