You are probably familiar with emperors such as Augustus or Trajan – men who ascended to the throne and took the Roman Empire to new heights. You’ve also probably heard of rulers such as Nero, Commodus, or Caligula – the ones who abused their power and treated Rome as their personal playground, where they were free to satisfy their most depraved vices. These are usually the two groups of emperors that get the most attention, the ones that sit at opposite ends of the spectrum, but where exactly does Domitian fit in?

If we go strictly by ancient sources, then that’s easy – he is firmly in the second camp, the one filled with maniacs and deviants. Suetonius, Cassius Dio, and Tacitus all wrote about Domitian, and they portrayed him as a vicious, paranoid, and power-hungry tyrant. But as you are about to find out, many of them also had personal grudges against Domitian, so perhaps they might not have been paragons of objectivity when they wrote about him.

Modern historians tend to have a more lenient view of the emperor. They don’t deny his ruthlessness and autocracy, but they think these were mixed in with efficiency, realism, practicality, and a genuine desire to improve Rome, with the end result being one of the most contentious and controversial reigns in the history of the Roman Empire.

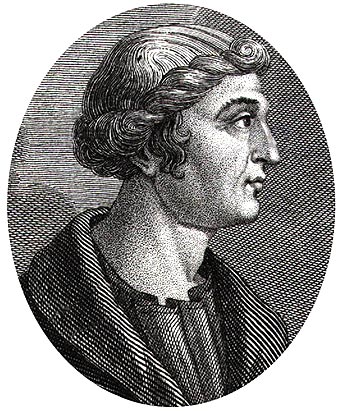

Credit: I, Sailko, CC BY 2.5

Early Years

Domitian was born Titus Flavius Domitianus on October 24, 51 AD, part of the short-lived Flavian Dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire for three decades during the second half of the 1st century. His father was Vespasian, a crucial emperor who brought some much-needed stability to Rome following the civil war caused by the Year of the Four Emperors, and who may have even saved the empire from collapsing just a hundred years into its existence. And if you would like to learn all about that hot mess, we have a Biographics video on Vespasian ready for your viewing pleasure.

Domitian’s mother was Domitilla the Elder, who died sometime before her husband became emperor. He had an older sister named, you guessed it, Domitilla the Younger, who also died before her family took power. Domitian married once, in 71 AD, to Domitia Longina, and the couple had one son together, who died young.

Let’s finish the family tree with Domitian’s older brother Titus, who ascended to the Roman throne after their father’s death. It would be pretty fair to say that many Romans, Vespasian included, looked to Titus to carry on the family name. Domitian grew up in the shadow of his brother, who had clearly been groomed and trained to take over the empire one day. Vespasian even trusted his eldest son enough to lead the charge in the First Jewish-Roman War. Therefore, nobody was really surprised when Titus was named the new heir and later became emperor.

By most accounts, Titus had a positive start to his reign, even when he was faced with the worst natural disaster in Roman history – the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which we covered on Geographics in our video on Pompeii, if you’re interested. However, all hopes of a long, successful reign quickly left when Titus fell ill with a fever and died suddenly in 81 AD, just two years after becoming emperor. Despite the fact that Domitian had previously only held ceremonial titles and never really had any actual responsibilities, he was now the new Emperor of Rome.

There was no love lost between these two brothers. Suetonius accused Domitian of openly plotting against his sibling and then leaving him for dead once Titus fell ill, seemingly more concerned with his ascension to the throne than his brother’s wellbeing. Even when Domitian was emperor and Titus was dead & buried, the sibling rivalry continued as Domitian “bestowed no honor upon him, save that of deification, and he often assailed his memory in ambiguous phrases, both in his speeches and in his edicts.”

The Reformer

Domitian wasted no time in becoming drunk with power. Almost as soon as he took the throne, he gave himself the modest title of dominus et deus – “master and god” – and made the Senate almost redundant by severely curtailing their powers. The two sides remained at odds with each other for all of Domitian’s reign. The emperor made no secret of the fact that he considered the Senate an obsolete remnant of a bygone era, and that he alone should be the one making all the decisions that would lead Rome into a new and glorious age.

This is the main reason why ancient historians were so rough in their treatment of Domitian, since many were senators themselves or were around in the same social strata. Suetonius, a contemporary of Domitian, described the emperor as “rapacious through need and cruel through fear,” while Cassius Dio said that Domitian was “not only bold and quick to anger but also treacherous and secretive” and that “there was no human being for whom he felt any genuine affection… but he always pretended to be fond of the person whom at the moment he most desired to slay.”

All of that being said, Suetonius does give credit where it’s due and admits that Domitian had a very hands-on approach when it came to ruling over his empire. You might be familiar with other power-mad emperors who basically treated Rome as their personal piggy bank, preferring banquets instead of budgets and orgies instead of oversight, without a care for the well being of their empire or its people, but it does not seem like Domitian fell into that category. He enacted many new laws, policies, and edicts, and got involved in all aspects of administration. We’re not saying they were necessarily good or improvements over the previous system, we’re just saying that there were a lot of them.

For starters, Domitian fought against nepotism and did not award many offices to his family members, even though this was a common occurrence at the time practiced even by his father, Vespasian. More than that, he opened many political offices to freedmen and equestrians, when such important positions were typically reserved only for the senatorial classes. He also ensured that justice was dispensed with diligence by sitting in on many tribunal hearings, targeting jurors and arbiters who were accused of accepting bribes. It seems that the suspicious nature and slight paranoia that usually accompanies a man in his position of power worked in Domitian’s favor because the level of scrutiny he enacted over his underlings kept corruption at a minimum. Even Suetonius had to admit that “he took such care to exercise restraint over the city officials and the governors of the provinces, that at no time were they more honest or just, whereas after his time we have seen many of them charged with all manner of offenses.”

Another curious aspect that goes against the whole “mad emperor” persona was that Domitian seemed to be a bit of a prude. When it comes to Roman emperors, we are used to hearing about all the weird sex stuff they were into, but if Domitian had a freaky side, he kept it very well hidden. Outwardly, he clamped down on licentious behavior and released guidelines for strict morals. He forbade public theater, as well as satire aimed at distinguished men and women. He openly condemned high-ranking officials who were caught with their pants down, both literally and metaphorically, and he enacted capital punishment on Vestal Virgins found guilty of breaking their chastity vows.

The only juicy bit of scandal from Domitian’s private life comes to us courtesy of Cassius Dio, who said that the emperor’s wife, Domitia, had an affair with an actor named Paris. Once Domitian found out, he had Paris murdered in the street and intended to put his wife to death, as well, until he was talked out of it by an advisor. He and Domitia became estranged and the emperor started a new relationship with a niece named Julia.

The Builder

When Domitian wasn’t busy passing laws and making edicts, he was rebuilding Rome. The eternal city had seen better days, having suffered one civil war and two major fires in the previous decades, including the Great Fire of 64 during Nero’s time, which destroyed almost two-thirds of the city. But this was a costly and time-consuming endeavor, and Domitian was not satisfied with merely making Rome the same way it used to be. He had his own ambitious construction plans to give it the grandeur he felt it deserved.

For starters, he finished two major building projects started by his father and brother – one was the Temple of Vespasian and Titus and the other was the famed Colosseum, or the Flavian Amphitheater, as it was called back then. Then, he renovated some of Rome’s greatest structures, which had been damaged in the prior decades, such as the Circus Maximus and the Pantheon. Finally, Domitian had his master architect, Rabirius, design a new palace for himself and build it on top of the Palatine Hill – a palace of unimaginable opulence and extravagance that would be the envy of all Rome. He called this architectural marvel the Flavian Palace and, indeed, it lived up to its reputation so much so that subsequent emperors continued to use it as their residence even after the Flavian Dynasty was long gone.

Temples also greatly benefited from Domitian’s attention, as the emperor was a devout man who regularly offered praise to the gods, particularly Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and justice. Domitian oversaw the fourth and final reconstruction of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, making it bigger and more spectacular than ever. This was the oldest and most sacred temple in Rome, but it had a tendency to get damaged a lot. Domitian’s father, Vespasian had just rebuilt it for the third time and it only lasted for a few years before burning down again. Domitian’s renovation seemed to be more sturdy, as the temple lasted for hundreds of years until the Romans turned to Christianity and stopped caring about it.

To show his devoutness, as well as score some bonus points with the common people, Domitian regularly organized games, fights, and races where he “presided at the competitions in half-boots, clad in a purple toga in the Greek fashion, and wearing upon his head a golden crown with figures of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, while by his side sat the priest of Jupiter and the college of the Flaviales, similarly dressed, except that their crowns bore his image as well.” During these times, Domitian awarded the people gifts of money and threw lavish banquets because he knew the secret to a long reign. Between the people, the army, and the Senate, you needed to keep at least two of the three happy in order to avoid being dragged through the streets and ripped to pieces by an angry mob. The Senate was out of the question, so Domitian ensured that he never got on the bad side of the soldiers or the plebeians.

The Soldier

If you are going to have a large army of well-paid soldiers, you might as well use it, right? That was Domitian’s thinking, and he went on the warpath very early in his reign, likely since he considered military glory to be an essential component of the new & improved Roman Empire he was working on.

His first target was a Germanic tribe called the Chatti, although his campaign didn’t really receive the reception he was hoping for. In 83 AD, Domitian used a very flimsy pretext to declare war on the Chatti and founded a new legion called Legio I Minervia to take them on. He easily scored some early victories, enough to return home to Rome and justify throwing a military triumph in his own honor, but historians of his time decried his war as “uncalled for” and a “mock triumph.” It was very much like the biggest bully in class beating up the dorky kid who ate paste and then bragging about it to all of his friends.

Tacitus made no secret of the fact that Domitian’s actions were motivated by jealousy of a general named Agricola, who was in charge of the Roman conquest of Britain and was out there winning some actual victories while the emperor was merely play fighting:

“He felt conscious that all men laughed at his late mock triumph over Germany, for which there had been purchased from traders people whose dress and hair might be made to resemble those of captives, whereas now a real and splendid victory, with the destruction of thousands of the enemy, was being celebrated with just applause. It was, he thought, a very alarming thing for him that the name of a subject should be raised above that of the Emperor.”

Tacitus was also Agricola’s son-in-law, so perhaps a tiny bit of bias there, but there is no denying that Domitian eventually put a stop to Agricola’s career without just cause, recalling him to Rome in 85 AD and then refusing to give him another military post, even though Agricola had been a successful commander since the time of Vespasian.

In 87 AD, Domitian ended the campaign in Britain altogether, abandoning the Caledonian territories, dismantling the fortifications, and moving the Roman border further down south. His plans soon became evident because Domitian had set his sights on a new ambitious target – the Kingdom of Dacia.

As early as 85 AD, the Dacians had begun conducting raids into Moesia, their neighboring Roman province. The attacks took on a more threatening nature when the Dacians met the Romans in battle and actually won, even killing the governor of the province, Oppius Sabinus, in the process. Clearly, a stronger military presence was needed to respond to this threat, which is why Domitian ordered his troops from Britain to withdraw and travel to Moesia. He assumed that five Roman legions led by General Cornelius Fuscus would be more than enough to handle the puny barbarian invaders, but he was wrong because the Dacians were led by their greatest-ever commander, King Decebalus. Cassius Dio certainly seemed to have more respect for him than he ever did for Domitian and he described Decebalus as “shrewd in his understanding of warfare and shrewd also in the waging of war; he judged well when to attack and chose the right moment to retreat; he was an expert in ambuscades and a master in pitched battles, and he knew not only how to follow up a victory well, but also how to manage well a defeat. Hence he showed himself a worthy antagonist of the Romans for a long time.”

When Fuscus launched his counteroffensive and drove the Dacians across the border, he thought the war was as good as won. Domitian had accompanied him up until this point, even though he remained behind the safety of city walls, far away from the battlefield. But now he was on his way back to Rome to prepare for his second triumph when he heard the news – Fuscus had crossed the Danube River into Dacia and walked right into an ambush. The general was killed, one of his legions was completely annihilated and the others were forced to retreat back to Moesia.

It was a complete humiliation for Domitian, but then it got even worse. The war continued for the next few years, with neither side gaining a decisive advantage. However, it wasn’t like the Dacians were Rome’s only enemy. Other tribes such as the Marcomanni, the Quadi, and the Iazyges were all harassing Roman borders and Domitian simply did not have the soldiers necessary to deal with all of them. In 88 AD, the emperor had no choice but to swallow his pride and accept a peace treaty with Decebalus, which was “Great news!” for Dacia because the treaty was very much in their favor.

Sure, Dacia was now a client kingdom of Rome, but the Dacians were laughing all the way to the bank as they built new fortifications and equipped their soldiers, all with Roman money and engineers provided by Domitian to keep them nice & quiet. The deal worked, but both the Senate and the army considered it utterly disgraceful. It wasn’t until almost 20 years later that Trajan corrected this “black eye” to Rome when he defeated Decebalus and conquered Dacia.

The Madman

Although Domitian was eventually successful in stabilizing his borders again, he never truly recovered from his war with the Dacians, which resulted in a humiliating compromise for him. Even Suetonius, someone who gave Domitian some credit in his first years as emperor, saw that the emperor went on a downward spiral, where he steadily gave into his paranoia and cruelty.

The second half of Domitian’s 16-year reign was marked by numerous executions. Up until that point, he was mainly content to simply neuter the Senate’s powers and then ignore them, but now he wanted them out of the way permanently. What followed was a purge of senators, ex-consuls, governors, and other officials who were executed for the most trivial reasons. Domitian put to death his own cousin, Flavius Sabinus, because he was once accidentally announced by a crier as “emperor-elect” instead of consul, while Sallustius Lucullus, the Governor of Britain, was executed simply for naming a new type of lance after himself.

Domitian’s growing paranoia certainly wasn’t helped by the fact that sometimes people were actually plotting against him. One such event occurred in 89 AD when the Governor of Germania Superior, Lucius Antonius Saturninus, mounted a rebellion against the emperor. Unfortunately for the upstart agitator, he was surrounded by other generals who were still loyal to Domitian, including the future emperor Trajan, and they managed to stamp out the revolt before it led anywhere. Even so, it still presented a convenient opportunity for Domitian to execute some more people he accused of being co-conspirators.

Obviously, things couldn’t go on like this forever. Everyone around Domitian lived in constant fear that they might be the next one on the chopping block. Ultimately, a new conspiracy was hatched, although the identities of all the participants remain a mystery. As Suetonius tells it, the main culprit was a court steward named Stephanus, who faked an arm injury in order to conceal a dagger within the bandages. On September 18, 96 AD, Stephanus gained a private audience with Domitian under the pretense of having uncovered a plot to assassinate the emperor. The only tiny little detail he forgot to mention was that he was part of that plot, so while Domitian was reading some document Stephanus had handed him, the steward pulled out his dagger and stabbed the emperor right in the crotch because he’d never heard of the heart or the neck, apparently. Anyway, while this might have raised Domitian’s singing voice a few octaves, it didn’t kill him, so a scuffle ensued between the two. When other conspirators heard the commotion, they entered the emperor’s chambers and stabbed him seven more times for good measure.

Thus came the end of Domitian and with it came the end of the Flavian Dynasty. He left behind a controversial legacy, which could generously be described as “a game of two halves” – the first one, at least, filled with ambition, reform, and potential, although, ultimately, they were replaced by failure, tyranny, and bloodshed.

Reactions to his death were mixed. Unsurprisingly, the senators “were so overjoyed, that they raced to fill the House, where they did not refrain from assailing the dead emperor with the most insulting and stinging kind of outcries.” The people of Rome didn’t really seem to care that much, but that could not also be said for the soldiers who quite liked Domitian. They wanted the emperor deified and his assassins executed, which was in stark contrast to the Senate’s wishes, who wanted Domitian’s memory to be entirely stricken from the history books. Obviously, the Senate didn’t get what they wanted, since we are talking about him right now, but without any heirs, they needed to select Domitian’s successor very carefully in order to avoid a new civil war.

They chose…poorly. The new Roman emperor was Nerva, a former consul who had served the empire since the time of Nero. Don’t get us wrong, Nerva seemed like a decent candidate. He was the first of the so-called “Five Good Emperors” – he reverted many of Domitian’s autocratic policies and swore never to execute a senator. But Nerva was already in his mid-60s when he took the throne and, as a lifelong bureaucrat, he commanded no respect from the army. He only ruled for a year-and-a-half and, in the middle of his reign, the Praetorian Guard revolted against him in 97 AD, took him hostage, and forced him to give up Domitian’s killers to be executed.

Once that had happened, it was clear that any authority Nerva might have once possessed was completely gone. Truth be told, his greatest attribute might have been his ability to admit that he wasn’t the right man for the job, which is why in 98 AD he willingly and peacefully transferred power to his adopted heir who was the right man for the job, Trajan.