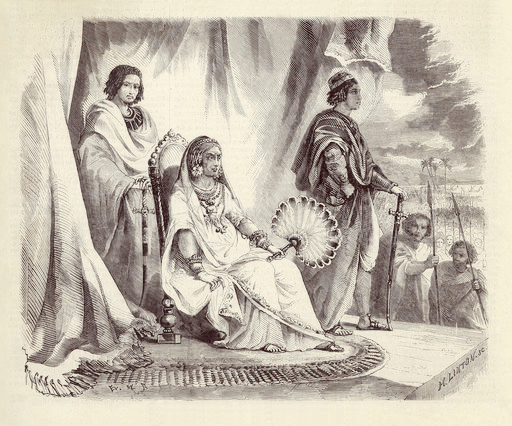

The history of Madagascar is rich in stories of conquest, piracy, colonial struggle and charismatic monarchs. Amongst one of the best-known characters of this epic is Queen Ranavalona I, who ruled the powerful Merina Kingdom, from 1828 to 1861.

A quick look into her past will reveal how she protected the independence of her island from the influence of colonial powers. But it will also highlight the ruthlessness of her actions, believed to have caused 2.5 Million deaths.

Titles often associated with her name include ‘the Mad Queen’, the ‘female Caligula’, or the ‘Bloody Mary of Madagascar’.

It must be said that most of what we know about Ranavalona, we know it through her enemies, so a healthy pinch of salt is advised.

Nonetheless, in today’s Biographics we will do our best to learn about the multiple facets of this ruler: one who became famous thanks to dramatic acts of bloodshed … but had a soft spot for bureaucracy and data processing!

One Day my Prince Will Come (down with syphilis)

Early accounts of Ranavalona’s childhood are scarce and contradictory. She may have been born in 1788, or in 1790.

At birth, she may have been named Ramavo.

According to some stories, she was a commoner of humble origins. According to others, she may have been the daughter of Prince Andrianampoinimerina’s cousin.

What is certain, is that she was born in the Merina Kingdom, the largest and strongest of the national entities which composed Madagascar at the time. Additionally, most accounts agree that her father thwarted an assassination plot against the Prince.

When Andrianampoinimerina became King, he rewarded his savior by adopting Ramavo as his own daughter, who he then betrothed to his son, Prince Radama. In a slightly less incestuous version of the tale, the young girl was adopted by Ralesoka, the King’s sister.

In 1810, Radama had ascended to the throne, aged only 18, but his young wife Ramavo was not automatically the Queen. The girl, now known as Ranavalona, had to contend with the Prince’s affections with another 11 wives! She may have been his first wife, but she wasn’t at all his ‘favorite’.

The two never had a close relationship, and Ranavalona never bore a royal child. Her situation at court, in other words, was rather shaky. Meanwhile, outside of the royal palace, Radama was accumulating successes.

In 1820, he signed a commercial treaty with the British Empire, which secured military equipment and training for his growing professional army. At the head of his troops, the King expanded the Merina kingdom, taking over almost all of Madagascar.

Then, he established a collaboration with the London Missionary Society, who opened schools, spread literacy and converted many locals to Christianity.

Finally, the modernizing monarch brought an end to the slave trade, a business which had greatly profited Merina aristocracy in the past. This drive for reforms definitely benefited the military power of the King, but Radama was not without opposition.

When he modernized the army, he ordered all his soldiers to keep their hair short. Demonstrations erupted, led by traditionalist women, who wanted to reclaim the ancestral right to braid the long hair of their warrior husbands.

Radama would not have any of that: he ordered for the leaders of the revolt to be brutally slain, and their remains fed to wild dogs. Further opposition simmered in the shadows: ultra-traditionalist aristocrats who grumbled against his apertures to European powers and Christian missionaries.

This may be why his death, in the summer of 1828 is regarded as suspicious.

According to one version, the King had been poisoned by his own wife Ranavalona, in cahoots with the traditionalists. More realistically, Radama had fallen ill with syphilis or cirrhosis and was suffering so badly that he cut his own throat.

Ranavalona now had to make a decision: disappear quietly into the night or fight for succession.

Reign in Blood

The rightful heir to the throne was Prince Rakotobe, eldest son of Radama’s eldest sister. He had been educated in England and was attuned to the late King’s pro-Western policies.

But Rakotobe knew that his claim was not 100% safe.

According to the Merina belief system, any child of Ranavalona would have taken precedence. Even if born after Radama’s death. And even if realistically not conceived by Radama! According to some accounts, Ranavalona was indeed pregnant at the time – and not with Ramada’s child. She feared that Rakotobe may attempt to assassinate her – and knew that offense was the best defense!

The widow occupied the Royal palace and rallied supporters to her cause: the ultra-conservative aristocrats and officers from her home village all came to her defense.

With her back covered, Ranavalona declared herself Queen of the Merina on August the 1st, 1828, claiming that this was Ramada’s wish. The following June, 1829, the Queen underwent a double accession, in which she would set the tone for a reign, divided between modernity and return to ancestral customs.

In a public coronation ceremony, she wore a splendid gown fashioned by a French tailor.

But in a secret rite, she was anointed with the blood of a freshly slaughtered bull. By the time she performed both rituals, she had successfully got rid of all rival claimants to the throne.

Her nephew Rakotobe had been gored by a spear. His mother had been starved to death. Most of their relatives were also executed. According to biographer Keith Laidler, thousands of suspected opposer met a similar fate, in a show of force designed to consolidate her as the ultimate ruler.

This, she made it clear to her subjects with her coronation speech:

“Never say she is only a feeble and ignorant woman, how can she rule such a vast empire? I will rule here, to the good fortune of my people and the glory of my name! … The ocean shall be the boundary of my realm, and I will not cede the thickness of one hair of my realm!”

Queen of Big Data

Some biographies claim that the Queen quickly undid most of Radama’s reforms: she severed ties with the British and restored local forms of worship against Christian influence.

But in reality, the shift was not so clear cut.

According to British diplomat and historian Mervyn Brown, during the first months of her reign Ranavalona acted entirely out of pragmatism. This meant that she oscillated between continuity with the late King’s pro-British policies and a traditionalist agenda – as she saw more fit and advantageous ways to consolidate power.

For example, on the 28th of November 1828, the Queen denounced the Anglo-Merina treaty of 1820, and on the 25th of March 1829 she expelled the British diplomatic agent Robert Lyall. But at the same time, she entertained a good relationship with the Christian preachers of the London Missionary Society, or LMS.

They were allowed to hold mass, convert locals, celebrate sacraments and run schools. In exchange, a community of expat artisans attached to the LMS made themselves useful by setting up workshops to manufacture soap, hydraulic machinery, and even gunpowder!

This last contribution was particularly well received in October of 1829. From her capital Antananarivo the Queen had to contend with a double threat: a rebellion of the Sakalava people in the West, and a French invasion on the East Coast.

The French colony in Réunion island depended heavily on cheap labor and supplies imported from Madagascar. A steady supply which was interrupted by the Queen in 1829.

When the Betsimisaraka people revolted in Eastern Madagascar, French King Charles X took the occasion to punish those pesky Merinas by ordering an attack on the port towns of Toamasina and Mahavelona.

The invaders however were first weakened by malaria, and then met fierce resistance from the Malagasy army. In July 1830, a revolution toppled Charles X and the new monarch Louis Philippe was less keen on expensive colonial adventures. Heeding British pressure, the French withdrew exactly one year later.

This was a great victory for the Queen, an image and confidence booster.

But the war had disrupted trade on the East Coast of her kingdom, which relied heavily on the export of cattle and rice to Mauritius and Réunion. Those goods were sold against hard foreign currency, which could be reinvested into the purchase of firearms and munitions.

The Queen was now short on income. And less cash meant less musket balls! And who could tell if the French were to return?

This is when the monarch developed a talent for bureaucracy – which may not make for internet headlines, but it surely helped her economy.

First, she developed an efficient network of civil servants on the East Coast. At the stroke of a pen, most of the military officers in the region were appointed Portal Authorities, with powers to regulate trade.

Then, she issued precise, frequent, regular instructions to these offices, relying on the written word – which was a departure from the practices of Merina Kings, who used to issue orders orally during official assemblies.

The Portal Authorities were instructed to attract new foreign buyers for their cattle and rice. When possible, they were to ask payment either in foreign currency, or directly in munitions to stock the Royal garrisons.

The next step was to regulate imports.

Ranavalona knew that dependency on imports for basic goods could leave her country at the mercy of European powers. Therefore, she ordered her civil servants to limit imports to the strict necessary, and to pay for these in local currency or by bartering with local goods.

As these practices took hold, the Queen established a two-way communication flow.

She was informed at all times of the levels of production of local goods, as well as the levels of import for the same commodities. The data was centralized and processed by the Queen herself, who was able to impose maximum quotas for imported merchandise.

This centralization of economic policy clearly required a tight grip, if not an iron fist.

Ranavalona would realize almost immediately if decentralized offices took advantage of her physical distance and issue decrees on their own accords. If a bureaucrat dared to deviate from her policies, he may expect a message like this:

“I have the sole authority to make law through my words. If you attempt to speak in my name your words will return to me like a bird of great destruction: you will be tried and punished.”

Or, even better.

“Though I am far away, I stand like a sentinel over you”

I think I found my new out of office auto reply.

Away from Christianity

After the East Coast was pacified, the Queen’s relationship with the LMS and the British community began to sour. In November of 1831, she issued a ban on sacraments: no more Malagasy could be baptised, and those who already were could not take part in the Holy Communion.

Then, her government cracked down on the Christian schools. Boys as young as 13 were taken away from class and most of them were enlisted in the Army.

The LMS feared for a complete closure of their educational programmes, but the Queen reversed her policies. It seems like she was more interested in beefing up her infantry, rather than damaging the well-run schools, and in the following years the number of pupils increased from 2,500 to 4,000.

It appears from then on, that the interplay between the Court and the Christian faith was to follow a series of wild mood swings, influenced by the most senior aristocrats in the traditionalist party. A watershed moment was the case of Rainitsiandavana, a Christian man who had begun preaching an inspiring message: according to him, Christ would soon return to set everybody free and abolish slavery.

Court officers interrogated him and his followers. And when he stated that a slave was the equal of the Queen, the soldiers did not like it one bit. The preacher and his followers were placed head down in a pit and killed by pouring boiling water over them.

The ultra-traditionalist party continued to feed the Queen similar stories of how Christians undermined her authority and scorned the traditional Merina religion. One account mentions that on hearing one of these stories “The Queen was so grieved and angry that she wept for about a rice cooking and vowed death to all Christians”

Well, did she?

Kind of, but not in such a direct manner.

On the 26th of February 1835, she sent a message to the missionaries: Malagasy could and would not take part any longer in any form of Christian worship. But missionaries and their friends could stay, if they had any useful knowledge or craft to impart.

Then, on the 1st of March the Queen issued a proclamation ordering strict adherence to ancestral customs. All Malagasy who were baptized, who had been praying to the Christian God, or who simply knew how to read, had to come forward and recant their faith.

Around this time, the Queen had realized that a French invasion was no longer a threat. Moreover, she had welcomed to court a useful ally: a shipwrecked French engineer called Jean Laborde.

Another rumored lover, the advisor had a broad grasp of metallurgy and munitions. With the Queen’s backing, he directed the construction of Mantasao, a factory town at the forefront of an ambitious program of industrialization.

With Madagascar heading to self-reliance, the Queen could finally do without the missionaries’ support, and could fulfil the anti-Christian policies favored by her supporters.

Another factor which may have caused the change in direction was a shift in the balance of power behind the scenes.

In the first two years of her reign, the Queen was heavily influenced by her young Prime Minister – and lover – Andriamihaja. Who, by the way, may or may not have been the father of the Queen’s son, Rakoto.

The Prime Minister was a supporter of King Radama’s previous policies, and therefore friendly to the missionaries and open to British influence.

But Andriamihaja had powerful enemies, an extremely conservative faction headed by three brothers of the Andafiavaratra family. Two of them were also rumored to be lovers of the Queen.

So, it may have been a result of a power struggle or plain jealousy, that this faction conspired to eliminate Andriamihaja. When the minister was accused of betraying the Queen with another woman, he was forced to undergo the trial of tangena.

But he preferred to have his throat pierced by a spear.

Bloodbath

I should now clarify what tangena was.

This was one of the many brutal practices introduced by Ranavalona, and/or her supporters, as she tightened her grip against dissension. Basically, if somebody was suspected of opposing the Queen they were forced to take a poison extracted from the tangena nut, which induces vomiting.

Then, they had to swallow three pieces of chicken skin. If they vomited up all three pieces of skin, they were considered innocent.

But if they died from the poison … well, that was taken as proof of guilt!

And if they survived, but did not throw up all the skins, they were also considered guilty and executed!

According to historian Gwyn Campbell, this form of trial claimed 100,000 lives in 1838 alone. Another brutal custom imposed by the ruler was torture by progressive amputation. A brutal fate imposed especially on non-ethnic Merinas, who also regularly suffered from pillaging and abuse from the army.

The most common form of mistreatment was the traditional practice of fanampoana: forced labor for those subjects who could not afford their taxes. The poorest among the Malagasy were pressed into service as builders, foot soldiers, or litter-carriers for the aristocracy.

Ravanalona had effectively reinstated slavery, causing thousands of deaths due to starvation, exhaustion, and disease. Christians were, of course, also a common target for elaborate punishment. In 1836, the army apprehended 14 Malagasy Christian leaders who had resisted orders to give up their religion.

Ranavalona ordered for them to be dangled by ropes over a rocky ravine. The ropes were then cut, and the martyrs plummeted to their deaths.

As years progressed, the Queen further descended into a downward spiral of morbid, grotesque folly.

The buffalo hunt of 1845 is often cited as an example.

On that occasion, Ranavalona ordered her entourage to take part in a large buffalo hunt, dragging along thousands of slaves and servants. The whole party numbered some 50,000 people, who built roads, burnt woods and leveled villages to make way for the Queen and her aristocratic friends.

As the expedition marched on, searching in vain for elusive buffaloes, starvation and malaria took their toll. According to Keith Laidler:

“In total, 10,000 men, women, and children are said to have perished during the 16 weeks of the queen’s ‘hunt.’ In all this time, there is no record of a single buffalo being shot.”

21 Skulls

Around the same time, Ranavalona had firmly decided that her island should be rid of all foreigners.

On the 13th of May 1845 she passed a new law, ordering that all foreigners should perform unpaid labour in the execution of public works. The expat community understandingly refused to obey, and were therefore ordered to leave Madagascar within 11 days.

British traders in Tamatave, on the east coast, sent a letter to the Governor of the British colony on the island of Mauritius, venting their grievances. Captain Kelly of HMS Conway was sent to investigate, alongside two French vessels, the Berceau and the Zelee.

The French decided to launch a punitive expedition, and Kelly was game!

The combined Anglo-French force attacked the fort of Tamatave on the 15th of June, reassured by the flimsy-looking defenses.

When they realised that the weak palisades were just a decoy, it was too late.

The well-trained Merina army had concealed their real barricades behind a decoy fort, and launched a counter-attack. The British and French Marines suffered 21 dead and 53 wounded, and hastily fled back to their ships.

At the end of the day, the 21 skulls of the dead Marines were impaled on spikes warning Europeans against further invasions.

The Queen may had imposed a regime a terror, but so far had succeeded in protecting her realm from colonial rule.

All the while, Ranavalona’s son Prince Rakoto had grown into a well-respected young man, who distanced himself from his mother’s policies. He did not approve of summary justice, execution by chicken skin nor disguised slavery. He became popular amongst the Malagasy, as he released prisoners or donated food to foot soldiers.

In the early 1850s, Rakoto had become good friends with a French businessman, Joseph Francois Lambert, who had become affluent in Mauritius thanks to the slave trade. Lambert had been invited to court after an incident in which he had saved with his ship some Merina soldiers surrounded by rebelling farmers.

Lambert had become wary of the Queen’s brutal policies. In 1854, he and Rakoto began plotting a coup to overthrow Ranavalona.

On the 28th of June 1855, the two conspirators signed a secret agreement. The Frenchman committed to garnering support to their cause in Europe. In exchange, he would get the sole right to exploit all minerals, forests and vacant estates in Madagascar. Rakoto agreed to receive only 10% of the profits.

The next step was to invite foreign intervention.

Lambert wrote to French Emperor Napoleon III, inviting him to invade and establish a protectorate.

In later years, the junior Bonaparte would be eager to stick his fingers in countless colonial pies. But at that time, he was influenced by the ‘Saint-Simon school’ of foreign policy, which stressed indirect rule and Catholic missionary activity over military intervention.

Undeterred, Lambert embarked for a tour of Europe, seeking to obtain political and military support to defeat Ranavalona and her army. But in 1857, he returned to the island empty handed.

As a last resort, Rakoto and Lambert enlisted help from the Queen’s advisor and possible lover, the shipwrecked engineer Laborde.

They finally decided to set the coup in motion. But it was a total disaster.

The Queen was kept well-informed by her network of spies. She knew all along what was coming but toyed with the conspirators giving them a false sense of security.

At the last moment, she struck, arresting all the participants, except for Lambert who escaped alive.

Rakoto and Laborde were spared, but everybody else was sent on a forced march across swampy lands and most died from malaria.

Legacy

Once again, Queen Ranavalona I had triumphed unscathed, and she would remain untouchable until the 16th of August 1861. This is when, to the frustration of her enemies, the sovereign died peacefully in her sleep.

At her funeral, a barrel of gunpowder went off accidentally, killing several mourners. A fitting violent end to a violent reign. The Queen was succeeded by Rakoto, who took the style of Radama II. His rule was short-lived, as he was assassinated only two years later.

Madagascar entered a period of steady decline, marked by increasingly weaker rulers. A period which ended with a successful French colonial invasion in 1896.

Today, Ravanalona’s legacy is divided, and divisive. Even in Madagascar, her tenure in power is remembered by some as the darkest period in the island’s history. Or by others, as an age of prosperity, solid economic policies and effective resistance against foreign invaders.

It doesn’t help that many of the stories which concern the Queen may or may not be true …

If you hail from that beautiful country, please let us know in your comments your thoughts about today’s protagonist. Was she a power-mad tyrant or model of self-determination against the excesses of colonialism?

SOURCES:

General Biographies:

https://www.madamagazine.com/en/die-schreckensherrschaft-ranavalonas-i/

http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2013/11/mad-queen-madagascar-ranavalona/

https://www.notablebiographies.com/amp/supp/Supplement-Mi-So/Ranavalona-I-Queen-of-Madagascar.html

https://owlcation.com/humanities/Queen-Ranavalonas-Reign-of-Terror

https://histoireparlesfemmes.com/2014/11/19/ranavalona-ire-reine-de-madagascar/amp/

Queen Ranavalona I and the missionaries

http://madarevues.recherches.gov.mg/IMG/pdf/omaly5-6_9_.pdf

Bureaucratic reforms:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3171909

Anglo-French expedition of 1845:

https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/battle-madagascar-1845/