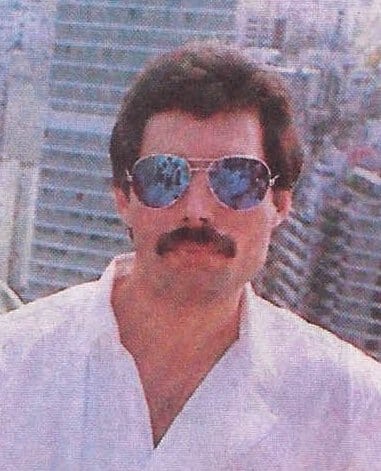

In the pantheon of rock star decadence, there’s one name that shines brighter than all others combined. Freddie Mercury was a man who did everything by extremes. The lead-singer of Queen, he possessed a personality bigger, brasher, and more flamboyant than even the band’s loudest songs. It was Freddie who threw the greatest party this side of Ancient Rome, in New Orleans in 1978. It was Freddie who turned seduction into a high-tempo art form; rushing offstage between songs to bed another beautiful man, before rushing back on again. Yet this showmanship went beyond mere hedonism. It was also Freddie who, in 1985, played a Live Aid set so bombastic, it’s estimated to have got a staggering 40% of the world’s population rocking along with him.

But while his lifestyle remains legendary, there was another side to Mercury. One far more complex than his onstage persona would suggest. Born to Indian Parsi parents, Freddie was a perpetual outsider. Arriving in Britain in 1964, he had to operate in a world in which both his ethnicity and sexuality marked him out as alien. This is the story of how that outsider went on to become perhaps the greatest performer of all time.

Queen in Argentina, published more than 25 years ago.

Being Faroukh Bulsara

When Faroukh Bulsara was born on September 5, 1946, he couldn’t have seemed more unlike the legendary rockstar he’d one day become. The eldest son of two Parsi Indians – a community of Zoroastrians who’d fled Persia to escape persecution – his family had its roots in the Bombay of the British Empire.

Indeed, the Empire was an outsize influence on the family’s life.

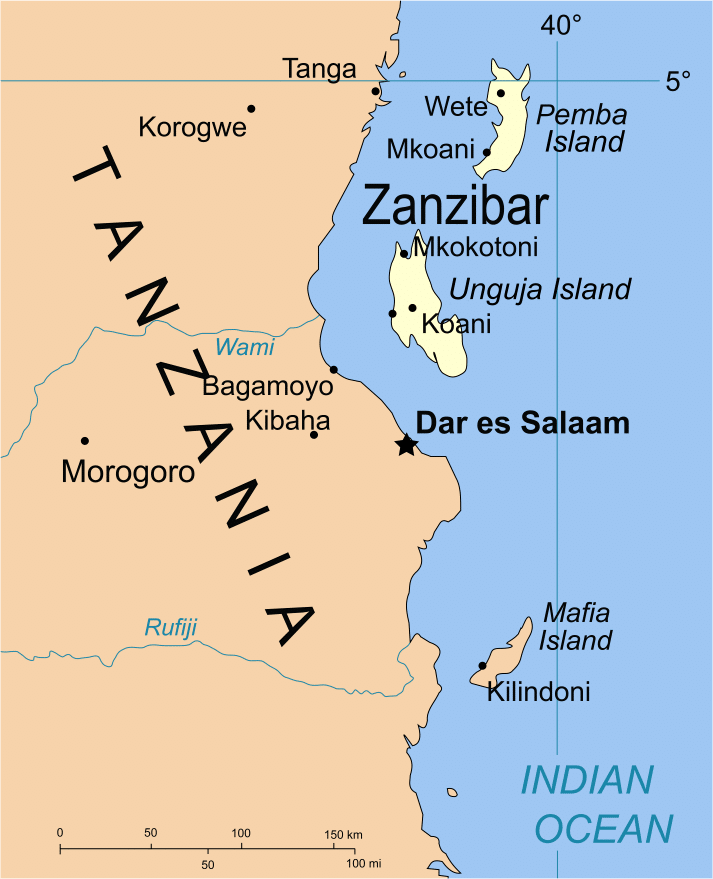

Bulsara’s dad was a civil servant working for the British on the African island of Zanzibar. Thanks to this, the family were able to live a life of comparative luxury. Their home in Zanzibar’s Stone Town came replete with servants and a nanny to look after young Faroukh.

The Empire also influenced the boy’s education.

While his parents were committed Zoroastrians, they sent the boy to Zanzibar’s Missionary school, where he was taught by Anglican nuns. It was at the school that the boy was nicknamed Bucky, on account of his overbite.

Yet this mild physical defect would turn out to be a secret power.

Many years later, when his Faroukh personality had been left far behind, Freddie Mercury would refuse to get his teeth fixed; lest doing so destroy his incredible four octave range. When he turned eight, the boy left Zanzibar, sent to now-independent India to study at an English-style boarding school.

It was during his years there that two important things happened.

The first was that Bulsara discovered he was utterly obsessed with music. Under the watchful eye of his grandparents in nearby Bombay, he formed his first band.

The second was something Bulsara never talked about much, not even when he was famous.

It was at boarding school, aged 14, that he had his first sexual experience with another boy.

Come 1963, Bulsara had graduated and relocated to Zanzibar, just as the island won its independence from Britain. By now, the childhood nickname of Bucky was gone, replaced by the much-less cruel nickname Freddie.

Back on the island, Freddie Bulsara divided his time between finishing his education and swimming in Stone Town’s clear waters. It was a fairly aimless existence, one befitting a teenager who didn’t yet know where he wanted to be or what he wanted to do.

Little could Freddie have known the decision was about to be made for him.

The Zanzibar Revolution exploded in January of 1964. Pitting the African majority against the ruling Arab elite, it killed upwards of 17,000 people.

The Bulsaras fled the violence, using British passports offered to the family when both India and Zanzibar exited the empire.

And that was how Freddie Bulsara at last came to settle in England.

By 1966, he was doing a design course in London, and feeling confident about a career in fashion.

It became commonplace to see Freddie strutting along Portobello Road dressed as a pirate, say, or working a clothing stall in Kensington in full-leather. Even at this early stage, he possessed a white hot streak of self-confidence, telling anyone he met that he was going to be a star.

Even though the bands he was now playing with were milquetoast nothings at best, that confidence still rubbed off on people. When Freddie strutted into the cult fashion store Biba in 1969, his attitude floored sales girl Mary Austin. The two began dating and, within months, were living together in a cramped apartment.

But it would be two other people Bulsara met around this time who’d change his life. One a mopey astrophysicist, the other a lothario studying to be a dentist. Their names were Brian May and Roger Taylor. Along with Freddie, they would soon form the band that would make them all famous.

Becoming Freddie Mercury

Since you’re watching a biography of Freddie Mercury, Rock God, rather than Freddie Mercury, Random Dude Who Did Nothing, you already know how the new band is going to pan out. But it’s worth pointing out just what an unlikely prospect Queen seemed in the early 70s. How divisive people found them.

As one music journalist memorably put it:

“Queen are either the future of rock’n’roll or a bunch of raving pooftahs.”

The thing was, nobody could really tell.

Queen had formed in 1970, the same year Faroukh Bulsara legally changed his name to Freddie Mercury. It was a change that ushered in a new public persona, one more outrageous than ever before.

As Roger Taylor said:

“It was Freddie who instilled in us the belief that we had to make people gasp every time.”

And making people gasp was something Queen excelled at.

Onstage, Freddie was already wearing mascara, codpieces, leotards; already exhibiting his incredible showmanship. For a lot of audiences, it was too much. Queen were slated in the music press, with Freddie himself singled out for harsh treatment.

Yet this criticism never seemed to land.

Instead, Freddie deflected it with winking self-deprecation, like when he declared of Queen: “we have more in common with Liza Minnelli than Led Zeppelin.”

At the same time, the band was slowly finding its footing. In 1971, bassist John Deacon joined, completing the classic Queen lineup. By 1973, the group had released their debut album, imaginatively entitled Queen. Off the back of this, they got a gig playing support for Mott the Hoople’s UK tour.

Despite this being a major step-up, Freddie was outraged he hadn’t been given a tour of his own.

“Being support is one of the most traumatic experiences of my life,” he half-joked in private.

Still, it was hard to complain. By winter, Queen were playing their first foreign tours, and well into writing their second album, the even-more-imaginatively-titled Queen II. Although Trident Records was barely paying him a living wage, Freddie still felt secure enough to propose to Mary Austin. Not long after, the band scored their first top ten hit with Seven Seas of Rhye.

So things were looking good as Queen headed off on their first American tour in April, 1974, again supporting Mott the Hoople.

But, sometimes, looks can be deceiving.

Rather than their big breakthrough, Queen’s America tour became a horrorshow when Brian May contracted hepatitis and the whole thing had to be canceled. As the group returned to Britain on an emergency flight, it’s easy to imagine how despairing that long trip over the Atlantic could’ve been.

But if there was anyone who could overcome despair through sheer force of personality alone, it was Freddie Mercury.

That summer, Queen returned to the recording booth.

For months, Freddie worked them like a demon, possessed by some volcanic drive. Worked to turn the band’s ailing fortunes around.

In this, he succeeded.

Sheer Heart Attack landed like a glitter bomb in November, 1974.

It was the album that introduced the world to the Queen sound: to that bombastic mix of opera, high-camp, and heavy rock.

As Mercury declared:

“We’ve found our identity now. And we have the feeling we can outdo anyone.”

But while Sheer Heart Attack would save the band commercially, it wouldn’t be the album that cemented their place in music history. No, that honor would go to a single Mercury was now just a year away from writing. A song that has been interpreted in as many different ways as the Second Amendment.

Freddie would call that song Bohemian Rhapsody.

And it would be his final breakthrough into superstardom.

All the Young Dudes

The lead-up to Bohemian Rhapsody’s release was outwardly one of success for Freddie Mercury and Queen. Sheer Heart Attack had turned them into serious players, transformed their earnings from a Dickensian pittance to Scrooge McDuck-style vaults of cash overnight.

Yet, behind the scenes, things were significantly less rosy.

As 1975 wore on, Freddie and Mary Austin’s relationship began to fray.

Although they still nominally lived together, Freddie was spending more and more time away, only retuning late at night – if he returned at all. Austin thought he was having an affair with another woman. And she was half-right. Her fiancee really was having an affair.

Only not with a woman.

David Minns was Mercury’s first, serious boyfriend.

Although their relationship didn’t last, it was a transformative event for the singer. Even while the two were sleeping together, Freddie began experimenting with gay hookups.

It was like a switch had been flipped.

Mercury had never been monogamous, seducing plenty of women even while he and Mary Austin were engaged. But, after Minns, the singer’s tastes shifted. As Brian May later recalled: “It was fairly obvious when the visitors to Freddie’s dressing room started to change from hot chicks to hot men.”

And there were suddenly a lot of hot young men around Freddie Mercury. Beautiful boys, sourced from all over the world.

As a result of this transformation, it’s been suggested by a whole lot of people that Bohemian Rhapsody was written as a secret coming out song. Now, we don’t want to read too much into what may just be a pleasing six minutes of operatic nonsense. But it’s not hard to see how Mercury’s inner life might’ve been reflected in his masterpiece.

Things finally came to a head with Mary Austin in 1976.

With Bohemian Rhapsody and its parent album Night at the Opera by now a smash success, Freddie Mercury sat down with Austin. In quiet, halting tones, he told her that he thought he was bisexual.

According to Austin, she responded by saying:

“No Freddie, I don’t think you are bisexual. I think you are gay.’”

Today, this looks like both Bi-erasure and… well, plain wrong. Although he showed a real preference for dudes, Freddie would have significant, sexual relationships with women well into the 1980s.

But not with Mary Austin anymore.

Austin moved out shortly after, although she and Freddie would remain close friends. Later, Freddie would tell people that she was essentially his wife. Still, Austin’s leaving seems to have been the catalyst for Freddie embracing his sexual identity.

He began appearing in clothing that mimicked gay, bisexual, and BDSM subcultures.

In 1978’s Don’t Stop Me Now, he cheekily sang about making both a “supersonic woman” and “supersonic man” out of you – perhaps a knowing nod to his own preferences. Yet, even as Queen turned up the camp to 11; even as Freddie began dressing in public as a Castro Clone, he never publicly discussed his sexuality.

Asked by a journalist to say once and for all if he was straight, gay, or bi, Freddie simply gave a toothy grin and replied:

“I sleep with men, women, cats, you name it.”

But while his public persona would never make a definitive statement one way or another, his private life would tell its own – often lurid – story.

Glorious Decadence

The late 1970s were years of eye-watering excess. As Queen shows got bigger and more choreographed, so did Freddie’s hedonism. Fun became something created with precision. Drugs were flown specially into cities to be on hand whenever the singer wanted a snort. Gorgeous men were kept in steady supply.

Freddie’s libertine side even appeared during shows, with it becoming standard practice for him to run backstage between songs, be sexually serviced, and then return to belt out the next number.

The outrageous high point of all this probably came on Halloween, 1978.

To celebrate the launch of Jazz, Freddie rented the Fairmont Hotel in New Orleans, and threw an eye-wateringly expensive bash to rival anything in Ancient Rome.

Transgender dwarves were hired to offer guests cocaine specially flown in from Bolivia. Erotic dancers suspended from cages vied for attention with naked waitresses, while gigantic, nude women sprawled elegantly across tables, lit cigarettes glowing in multiple orifices.

Beautiful models of both sexes wrestled in a pool of raw liver. Firebreathers and drag queens competed for space with a man biting the heads off live chickens. In the expensive marble toilets, prostitutes of both sexes offered their services for free. And, of course, everywhere as far as the eye could see were mountains and mountains of drugs.

It was Mercury in a nutshell: operatic, bonkers, brilliant, camp, and not a little perverted.

It was also everything his detractors hated about him.

Already perceived as all style and no substance, Queen’s overwrought excess turned them into critical whipping boys. Freddie was delighted. Whenever critics put the question to him, he retorted:

“All true, darling. We’re the most preposterous band that’s ever lived.”

And then, one assumes, stuck his nose right back in a handy bag of Uncle Escobar’s Finest.

Yet while Queen as a whole earned a reputation for excess, it was really Freddie who was the mad, shooting star – burning through the skies at 200 degrees Fahrenheit.

In 1980, the singer settled in a luxury apartment in New York City.

Almost every night, he’d hit a trendy club, seduce as many people as he could, and funnel them back to his apartment. When he woke up at 4pm the next day, there might be hordes of gorgeous young men who needed to be chased away before the madness could begin afresh.

It was a crazy time, even by rock star levels. Yet, it also seemed to be freeing.

Finally, Mercury was becoming the icon he’d perhaps always dreamed of being. The uninhibited, bisexual music god his young self could’ve hardly dared imagine.

Sadly, this freedom wouldn’t last.

In early September of 1982, Freddie Mercury turned up at a New York doctor’s office, complaining of a weird white spot on his tongue.

Today, we know it was likely an early sign of the HIV infection he’d probably picked up that summer. But, back then, AIDs was only just starting to seep into the public consciousness. In fact, the name “AIDs” was still a couple of weeks away from being coined.

But while that meant no sudden outing in the press, no stigma attached to Mercury’s name, it also meant something else.

No cure.

For the rest of his life, Freddie Mercury’s body would be slowly eaten away by the disease he hadn’t even known existed. The disease he wouldn’t even be officially diagnosed with until 1987.

Tragically, his days were already numbered.

Lows and Highs

If you were to plot Queen’s fortunes across the 1980s, they would resemble one of those jagged share-price graphs with the arrow shooting wildly up and down. On the one hand, the band scored its biggest single yet with Under Pressure, sometimes known to delusional white rappers as Ice Ice Baby.

They also cracked South America, playing what was then Brazil’s biggest-ever rock concert.

On the other hand, their US sales took a battering as Freddie’s queerness became more overt; before falling through the floor when the band appeared in drag for their video to I Want to Break Free.

At the same time, tensions backstage were resulting in fistfights between members, including one at an Italian festival that turned into a full-on brawl.

But perhaps the nadir came in 1984, when Queen played South Africa.

At the time, Nelson Mandela was still in prison, and the world was boycotting the Apartheid regime. Into this, Queen stepped to play eight nights at a whites only entertainment complex. The resulting furore nearly killed their reputation. Queen were handed a massive fine by the musician’s union, and were professionally ostracized.

Yet, this stupid, self-inflicted low would be followed by the band’s – and Freddie’s – greatest high.

In 1985, the band received a call from Bob Geldof, asking them to play a twenty minute set for Live Aid – a concert designed to raise money for famine relief in Ethiopia. Broadcast to 110 countries, with global viewer numbers reaching 1.9 billion, Live Aid was simply the biggest concert in history. Everyone from the Beach Boys, to Sting, to David Bowie was playing.

Yet, it would be Queen that stole the entire show.

Unlike some of the other artists, Freddie knew this was performance on a grandiose scale. Their twenty minutes would be the hits and nothing more.

And Freddie was going to give it his all.

Today, Queen’s Live Aid set is legendary. With a showmanship probably never seen since, Mercury electrified the crowd. His energy, his passion, were practically superhuman.

It’s estimated that, at one point, as much as 40% of the global population tuned in to rock along with him.

As career peaks go, this was a veritable Everest. That same year, Freddie also hit a new high in his personal life. In March, he met Irish hairdresser Jim Hutton at HEAVEN gay club in London. Originally, Hutton was just another conquest. But, after a few weeks of fooling around, Hutton told Freddie he would have to choose between keeping him, or keeping up his lothario ways.

Incredibly, Freddie chose Hutton. The two would be together until the end of Freddie’s life.

In short, Freddie Mercury in 1985 had everything: the respect of the world; a steady, non-volatile relationship; and more money than he could ever realistically spend. But this was sadly just a temporary high.

The very next year, the arrow would come plunging right back down to earth.

By 1986, it was clear that Freddie was seriously ill. His appearance became gaunt, like a starving man. Rumors began to swirl in the British press that he might have AIDs. The following year, two of his friends died from the virus. Not long after, a former manager-turned-boyfriend outed the singer to a British tabloid.

Already feeling hurt and betrayed, Freddie at last bit the bullet. Around Easter, 1987, he went for an HIV test.

You already know what the results were.

At first, Mercury only told Jim Hutton. Retreated to his Kensington home, only rarely venturing out. In 1987, there was only one possible outcome to a positive HIV test: death.

Aged barely 40, Freddie was already living out his final years.

Who Wants to Live Forever?

Freddie Mercury’s final years were almost unbearably sad. From a hedonistic rock god, he became a recluse, only ever venturing out to work in the recording studio.

Still, at least he wasn’t alone.

Jim Hutton remained by his side, becoming almost as much his carer as his lover. Mary Austin, too, was still around. She spent as much time with Freddie as possible in those final years – still the only person the singer felt he could really relate to.

Yet, even as he was dying, Freddie still retained his acid tongue.

Asked if he thought Queen’s music would last, he wryly responded:

“I don’t give a f**k, dear. I won’t be around to worry about it.”

The final end came in November, 1991.

On the 23rd of that month, Mercury at last released a statement, confirming to the world that he had AIDs. Well, maybe it’s unfair to say Freddie released it. According to Jim Hutton, Mercury spent his last days on Earth dosed up to his eyeballs on morphine, drifting in and out of consciousness.

It had been a deliberate decision to keep his diagnosis a secret until it no longer made a difference.

Freddie Mercury died the next day of bronchial pneumonia, aged only 45. Hutton – still playing the role of carer – was changing the star’s clothes as he passed away. As he later said:

“While I was putting his boxers on I knew he’d gone. I went into my bedroom and stopped a carriage clock Freddie had given to me: the time was 12 minutes to 7.”

When the news broke, hundreds of fans turned up outside the home to pay their respects. There was talk of a grand funeral – a final party to send Mercury off into the Heavens. But Freddie Mercury had already died, perhaps months earlier. In those last days, Faroukh Bulsara had been all that remained.

And he wanted a small, traditional Zoroastrian funeral.

Freddie’s body was cremated on November 27, 1991. Along with the bulk of his estate, he left his ashes to Mary Austin, who agreed to scatter them somewhere secret.

The location she chose remains unknown to this day.

In the wake of Freddie’s death, Bohemian Rhapsody was rereleased in Britain, where it shot to the top of the charts. All royalties went to the Terrence Higgins Trust, a UK charity combating HIV and AIDs.

Yet this wasn’t the end of Mercury’s time in the charts.

Before he died, the singer had hurriedly recorded vocals for several new songs, which the other members of Queen then set to music and released as a last hurrah. For a brief period in the 1990s, it almost felt like Freddie – or at least his ghost – was back, and as talented and outrageous as ever.

Today, nearly 30 years after his passing, the legacy of Freddie Mercury still lives on. Even those who consider Queen the epitome of style over substance acknowledge he was a one of a kind performer, with a unbelievable vocal range.

He also remains legendary for his personal life. Since 1999, Bi Visibility Day has been celebrated every September – a month chosen purely for being the one Freddie Mercury was born in.

Yet, for all his influence in other areas, it will always be his music that Freddie is best remembered for.

Here was a man of almost unbelievable talent; a man with a voice that could sell quiet tragedy as easily as it could sell operatic bombast. In the end, it was a talent that allowed him to live up to his own mission statement: to become a star, a global icon.

There will likely never be another Freddie Mercury. But the music he left us with is already enough to ensure his name lives on for centuries.

Sources:

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (paywall or free with British library card – more of a general Queen bio than a Freddie bio): https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-49895?rskey=obQ0De&result=2

BBC: Who was the real Freddie Mercury? https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20191010-who-was-the-real-freddie-mercury

Uncut, the full story of Queen: https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/queen-it-was-all-like-a-fantasy-to-see-how-far-we-could-go-18631/

Freddie’s bisexuality and HIV diagnosis: https://www.hivplusmag.com/entertainment/2017/9/05/freddie-mercurys-life-story-hiv-bisexuality-and-queer-identity

Bi-erasure: https://www.out.com/music/2018/9/05/remembering-freddie-mercurys-bisexuality-his-birthday

Mary Austin: https://www.biography.com/news/freddie-mercury-mary-austin

Jim Hutton: https://www.irishcentral.com/culture/entertainment/freddie-mercury-irish-partner-jim-hutton

Freddie’s roots in India and Zanzibar: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-freddie-mercury-race-religion-name-change-20181102-story.html

Freddie and Zanzibar: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45900712

Slightly odd, very old fansite that nonetheless has a load of great details on his early years: http://www.freddie.ru/e/bio

Making Sheer Heart Attack: https://www.loudersound.com/features/queen-we-went-to-extremes-we-put-ourselves-under-pressure

Making Under Pressure with David Bowie: https://www.biography.com/news/david-bowie-queen-under-pressure-recording-session

Brian May hepatitis: https://brianmay.com/queen/queendiary/part3.html