If you’d been watching British politics in the early 1930s, chances are there would’ve been one name on your lips. Oswald Mosely was handsome, charismatic; known for setting crowds alight with his passionate speeches. An aristocrat with a huge working class following, he was perhaps the only politician able to unite voters of both major parties. Regularly tipped as a future Prime Minister, it was said he could one day be Britain’s greatest leader.

But that never happened. Instead, Mosley chose to take his career down a much more dangerous path. The path marked “fascism”,

At Britain’s leading fascist, Mosley was able to command armies of Blackshirts. He received funding from Mussolini, and was friends with Adolf Hitler. Had the Nazis conquered Britain, he would’ve almost certainly been made ruler of a fascist UK state. Instead, this one-time political superstar saw his career and reputation destroyed in the firestorm of WWII. A joke to some, a dire warning from the past to others, this is the life of Oswald Mosley: Hitler’s man in Britain.

Oswald Mosley

The Man-Child

For a man who’d one day style himself a champion of the poor, Oswald Mosley’s background couldn’t have been more privileged. Born in London on November 16, 1896, he came from a family embedded in the aristocracy. His grandfather – also Oswald Mosley – was a baronet; while his father – also, confusingly, Oswald Mosley – was a rich playboy.

And, yes, that’s way too many Oswald Mosleys running around for one video.

Luckily, the three Oswalds were mostly known by their family nicknames. Grandpa Mosley was “John Bull”, while baby Mosley was known as “Tom”.

Still, despite his privileged status, life wasn’t easy for young Tom Mosley. His father was a serial adulterer and bully, who belittled his son mercilessly. The abuse got so bad that Mosley’s mum Maud took the boy and went to live with grandpa John Bull when Tom was only five.

There, the boy was spoiled rotten. John Bull apparently saw Mosley as an ideal replacement for own his disappointing son, while Maud regarded him as both a son and a substitute husband, calling him her little “man-child”.

It was meant affectionately. But the image it conjures – of a grown man acting like a spoiled kid – would be spookily prescient. The rest of Mosley’s childhood passed like that of any aristocrat. Before turning ten, he was sent away to preparatory school; and from there on to Winchester.

He became a competent boxer and world-class fencer, before heading to Sandhurst at 16 to train for the military.

By now, Mosley had grown into a tall, athletic young man with movie star looks. He’d also grown into something of a colossal dick. At Sandhurst, he became notorious for getting drunk and sneaking into town to pick fights with – or sometimes just beat up – the lower classes.

After one rowdy brawl with another student, he was even suspended.

But he wouldn’t spend long cooling his heels, because the British military was about to need every able-bodied man it could get. When WWI broke out in summer, 1914 Mosley was immediately recalled. Volunteering for the Royal Flying Corps, he trained as a pilot and, by Christmas, was flying reconnaissance over enemy lines.

With airplane technology in its infancy, this was a dangerous job.

But it wouldn’t be while on some urgent mission that Mosley sustained his lifelong injury.

In early 1915, Tom was back doing training flights at Shoreham when his mother came to watch. Wanting to show off for mummy, the man-child tried a difficult maneuver, and sent the plane crashing to Earth. It took a year of operations to save his broken leg, leaving Mosley with a permanent limp.

After that, it was desk duty.

Still, this was no bad thing.

Sent to work at the Foreign Office, Mosley found himself in a London denuded of young men, with a limp he could pass off as a sexy “war wound”. And so, while most men his age were fighting in the trenches, Mosley spent his evenings leaping into the beds of society women, and his days charming their rich and powerful fathers.

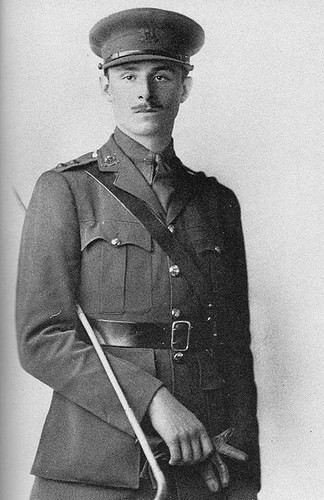

Oswald Mosley during the First World War.

By 1918, he was firmly connected to Britain’s political elite. And that was fortunate.

With the war over, it was time for the UK to hold its first election in years.

The election of 1918 is known as the Coupon Election, because the Coalition government sent out lists of candidates it felt had supported the war effort. For a public still flush with victory, seeing a candidate’s name on these coupon lists was a sign they were a patriot. Most coupon candidates won their seats.

Want to guess who managed to finagle his name onto that list?

That December, aged just 22, Tom Mosley was elected a Conservative member of Parliament.

It was the beginning of one of the wildest political rise and falls Great Britain had ever seen.

Revolution by Reason

If the previous decade had seen Mosley farting around, enjoying life, the 1920s would see him laser-focused on advancing. In May 1920, he strategically married upwards, seducing the daughter of Lord Curzon. The King and Queen attended their wedding.

But Mosley felt little love for poor Lady Cynthia. Although she bore him three children, he was serially unfaithful, seducing both her sister and stepmother.

Still, treating his wife like trash didn’t stop Mosley’s star from rising.

In the Commons, he began attaching himself to highly-visible underdog causes.

When one of those causes was Irish independence, his own party became so hostile that Mosley quit, sitting as an independent. But he’d soon find a new political home. In December of 1923, Britain’s second election in 13 months produced a shock outcome. The Conservatives lost their healthy majority; and second-place finisher Ramsay McDonald was able to form the first Labour government in UK history.

Although it was a minority government, momentum suddenly seemed to be with Labour.

In March, Mosley joined the party. It likely seemed a shrewd career move.

But then came the snap election of October, 1924 and Mosley watched in horror as the Labour vote collapsed. Not only did the Conservatives win a landslide, but Mosley lost his seat to Neville Chamberlain.

It’s easy to imagine Mosley now crawling back to the Tories, his tail between his legs.

But, unexpectedly, Tom stuck with his new party.

Over the next few years, he underwent a rapid transformation from layabout Toff to outspoken friend of the people. He toured British slums, where he deplored the condition of working class housing.

During the General Stike of 1926, he paid the wages of striking miners from his own pocket.

Larger Image Image Zoom Buy a print of this today Use this image Oswald Mosley by Glyn Warren Philpot oil on canvas, 1925 30 in. x 25 in. (762 mm x 636 mm) Lent by the sitter’s son, Lord Ravensdale, 1984 Primary Collection NPG L184.

He even traveled to the US and spent time with Franklin D. Roosevelt; although rumors he followed this with a trip to Birmingham to meet a family of flat cap-wearing gangsters remain unsubstantiated.

Before long, Mosley was convinced he’d identified Britain’s problems.

To his mind, international finance was the driving force to the misery he saw all around him.

As he polished his speaking style, becoming a master at whipping up listeners’ emotions, Mosley began to preach that a command economy was the only way forward, and Labour the only party that could deliver it.

On this front, he’d be sorely disappointed.

In spring of 1929, Britain’s election returned another near-win for Labour. Once again, the party formed a minority government. By now a Labour stalwart, Mosley entered the new government assuming he’d get a plum post like Foreign Secretary.

When he was instead placed in an advisory role outside cabinet, he threw what can only be described as the man-child tantrum to end all tantrums. But Mosley soon realized his new job – designing schemes to stimulate employment – was the perfect in-road for his theories.

As the Great Depression bit that winter, Mosley drafted proposals for investment in public works. For a protectionist market.

Unfortunately, the Prime Minister was less than enthused.

In January, 1930, Ramsay McDonald got tired of all of Mosley’s proposals, and basically told him: “dude, your ideas suck, you suck, and your suckiness is making me look bad. Stop it.”

It was the end of the line for Mosley and the government.

Shortly after, Mosley resigned with a passionate, hour-long speech in the Commons that electrified the press. In the aftermath, people began openly saying that Mosley was right. That he was the fresh face who should be leading the Labour party, not stuffy-old Ramsay McDonald.

Mosley was even tipped as a future Prime Minister. His ideas just the thing the country needed.

But Mosley’s ideas were about to get a whole lot crazier.

Descent into Fascism

In politics, they say timing is everything. And, in 1930, Oswald Mosley was convinced his time had come.

Across the year, he sounded out Labour MPs about a brand new party, one far closer to the working people than McDonald’s stuffy-ass Labour. At the same time, he courted Conservatives with economic proposals grounded in exploiting the empire’s colonies.

When he published his Mosley Manifesto, people as varied as HG Wells, John Maynard Keynes, and future Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan all expressed interest.

Finally, in spring of 1931, Mosley decided to strike.

Taking a donation of £50,000 from a motor car magnate, he used it to found a new, populist party – imaginatively called the New Party. Consisting of Mosley, five rebel Labour MPs, and one rebel Conservative, it was a humble beginning.

But great things can grow from small seeds. And Mosley’s stock was still rising, especially among those already feeling the Depression’s pinch. It’s not too hard to imagine how Mosley could’ve really seized this moment. Turned himself into the charismatic leader he’d always felt himself to be.

Instead, the young aristocrat watched in shock as that moment slipped through his fingers.

Just as the New Party launched, Mosley was hospitalized for six weeks with pneumonia.

By the time he’d recovered, the party’s moment in the spotlight had already come and gone. The only ones still paying attention were the Communists, who were seriously pissed about the New Party stepping on their turf. When Mosley tried to regain his momentum by holding mass meetings in working class areas, the Communists caused massive disruption.

So Mosley hired protection. A gang of hoodlums, led by the boxer Kid Lewis.

It would be the end of the New Party.

The stewards Lewis recruited were young, tough men who were super-enthused about beating up Commies. In that era, hardcore anti-Communists tended to be on the extreme-right. As more of them joined Mosley’s army, it was hard to wave the smell of fascism away.

But the deadliest blow came that summer.

With the country in chaos, Ramsay McDonald abandoned his minority administration. Instead, he embraced the Conservative and Liberal parties in a National Government. When he put this new government to the electorate, it won the biggest landslide win in UK history.

The New Party, by contrast, didn’t win a single seat.

In the aftermath of his humiliating defeat, Mosley abandoned regular politics. He went abroad, looking for inspiration.

His first stop? Mussolini’s Italy.

Although the New Party had flirted with fascism, it wasn’t until Mosley saw a genuine fascist state in action that he fully embraced far-right politics. Shortly after, Mosley was at a party when he got chatting to a young woman. Mosley’s new passion for fascism blew the girl’s mind. She fell madly in love with him.

That young woman was Diana Mitford, and meeting Mosley would change her life.

In autumn, 1932, Mosley at last did the inevitable.

The British Union of Fascists (or BUF) was founded on October 1. Surrounded by former New Party thugs decked out in black shirts, Mosley declared his true colors to the world. It was the final end of Oswald Mosley, the man who would be Prime Minister. And the beginning of Oswald Mosley, Britain’s most-dangerous fascist.

The Übermensch

In summer of 1933, Diana Mitford and her younger sister Unity traveled to Nuremberg to witness the Nazis’ victory rally. By now, Diana was both Mosley’s mistress, and a hardcore fascist fangirl. But soon she and Unity would be something else, too.

In Germany, they would become close friends with Adolf Hitler. Back home, Diana’s lover was already modeling himself on Germany’s new leader. BUF rallys became Nazi tribute acts, complete with lightning-bolt flags; seig heil salutes; and Mosley ranting onstage like a man possessed.

At the same time, the party was deliberately targeting young, violent men; luring them in with sport events and male camaraderie, then preying on their grievances to radicalize them.

Yet, at this stage, no-one in the British establishment could see the danger.

People in 1934 genuinely admired the BUF. Future king Edward VIII wanted Mosley to be Prime Minister. The Daily Mail ran headlines declaring “Hurrah for the Blackshirts!” Membership hit 50,000. For a while, it genuinely looked like Mosley’s brand of British Nazism might have mass appeal.

And then came the Olympia Rally.

Held on June 7, 1934 at the Olympia Arena, the rally was meant to be the biggest BUF meeting yet, with Mosley holding court before 10,000 spectators.

Unfortunately, planted among those spectators were 500 anti-fascists, who took turns causing disrupting the meeting until it was almost impossible to speak. The idea was to provoke a reaction, which they certainly got. Mosley’s Blackshirts beat dozens of the protestors unconscious, to the delight of the committed fascists in the crowd.

But while the beatings played well in the arena, the general public was much more queasy.

In the wake of the Olympia violence, newspapers withdrew their support for Mosley. The BBC banned him from the airwaves. By 1935, this oldey timey no-platforming had seen the BUF shed 90% of its membership. All that remained were the real hardcore fanatics.

So Mosley began to pander to them as hard as he could.

That year, 1935, the BUF adopted an avowedly antisemitic platform.

We can’t give you the worst examples of what Mosley said, lest we trigger YouTube’s algorithms and see yet another of our videos get demonetized, but Mosley openly called for the deportation of all Jews, declaring “Britain for the British.”

Worse still, he backed this hateful rhetoric up with action.

On October 4, 1936, over 3,000 Blackshirts marched into the Jewish district of Stepney in East London, a show of force designed to intimidate. Although a vast crowd of ordinary people blocked their path, the march devolved into a riot that saw hundreds injured.

Today, the Battle of Cable Street is seen as a turning point, the moment Mosley lost the general public for good. But, at the time, it was a victory for fascism. Mosley declared the government had “surrendered to Jewish-Communist violence”. BUF membership immediately spiked.

But, by then, Mosley was already on his way to Berlin.

Back in 1933, poor, abused Lady Cynthia had died, leaving Mosley free to pursue his relationship with Diana Mitford.

Now, they were taking things to the next level.

On October 6, 1936, the two married in secret at the home of Joseph Goebbels.

The guest of honor was Adolf Hitler, who presented the couple with a signed photograph as a wedding gift. Five days later, 200 youths from the BUF flooded into Mile End in London, smashing Jewish shops and attacking anyone they thought to be Jewish.

It was one of the worst incidents of anti-Semitic violence in modern British history; and a disgusting high point for Mosley’s fascists.

Luckily, his career would be all downhill from here.

Collapse

The biggest hammer blow against Mosley came just months after the Battle of Cable Street. That December, the National Government decided it no longer gave a damn, and banned both the wearing of political uniforms, and the right to hold political processions.

At the same time, the owners of venues across the nation agreed to bar Mosley and the BUF from renting their properties. Today, of course, Mosley could just reach out to his fascist fanboys on Twitter or Parler; but in the 1930s, loss of venues basically meant losing all your publicity.

And so Mosley vanished. For a bit. Across 1937, he was so far out the public view that he might as well have temporarily ceased to exist. But Mosley was nothing if not determined. In 1938, he hit on a brainwave. A way to resurrect the BUF’s reputation among the genteel classes.

The Blackshirts would become avowed pacifists.

By now, it was obvious to everyone in Britain that another major war was coming, one very few people wanted to be a part of. It was an era when the Chamberlain government was pursuing appeasement. When the Prime Minister could dismiss the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia as a “quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing”.

In such circumstances, it’s perhaps no surprise that Mosley saw his popularity rebound.

Over the next 18 months, Mosley cultivated a dove-like image with the British public. Mass rallies were held where he implored people to stay out any future war. These rallies were a moderate success. By mid-1939, there were even whispers that Mosley might be in the process of a political comeback.

But then the war actually arrived, and the BUF’s popularity again collapsed.

Although Mosley told his followers not to work as agents for Germany, nobody believed he meant it.

Indeed, his former deputy leader – William Joyce – had already fled to Berlin and begun making Nazi propaganda under the nickname ‘Lord Haw Haw’. There was no way the government was going to leave Mosley and his potential fifth column running around free in wartime.

On May 23, 1940 – just after Churchill became Prime Minister – the BUF was banned, and 800 of its members arrested as security risks. Mosley was imprisoned. Two months later, Diana Mitford was also arrested, the couple’s signed photo of Hitler found hidden in their baby’s crib.

That same year, they were interned together at Holloway prison.

And that was it for Tom Mosley’s public career.

Although the pair were released on compassionate grounds in November, 1943, it was to a general public that now considered them about as trustworthy as the lovechild of Judas and Benedict Arnold. The two stayed under house arrest until the war’s end in 1945. The moment they could, they abandoned England.

After an unhappy stop in Ireland, the couple eventually wound up settling in a fancy house outside Paris, from where Mosley incessantly plotted a comeback. He reinvented himself as a passionate European, calling for a united Europe to end the incessant cycles of bloodshed.

But while his pro-Europe speeches were full of appeals to peace, you only had to scratch the surface to see the poison still lurking in his veins.

Mosley’s Declaration of Venice, for example, suggested forcibly dividing Sub-Saharan Africa into Black and white nations, and then essentially using the Black nation as both cheap labour, and a captive market for European products.

At the same time, Mosley continued to rabble rouse on hot button issues. On one occasion while back in London, he demanded the immediate deportation of all non-whites from Britain and a ban on interracial marriages.

As his son Nicholas wrote afterwards:

“I see clearly that while the right hand dealt with grandiose ideas and glory, the left hand let the rat out of the sewer.”

Still, it no longer really mattered what Tom Mosley said.

In 1959, and again in 1966, the former political superstar stood for election as an MP. Both times he got so few votes that calling him an “irrelevance” would’ve overstated his importance. After his 1966 failure, Mosley officially retired from political life.

Although he edited a far-right magazine, and kept in touch with a vast number of important figures, that was essentially it for his influence on public life.

Well, at least until he turned up as the bad guy in Peaky Blinders.

Oswald Mosley died on December 3, 1980, at his home in France. Cremated, his ashes were interred in Paris’s Père Lachaise cemetery, far away from the island nation he’d once imagined he could lead. For her part, Diana Mitford lived on until 2003. In all that time, she never once expressed regret for befriending Hitler or for supporting Germany in WWII.

Today, Oswald Mosley is little more than an interesting “what if?”. A historical footnote off whom you can hang all sorts of alternate history ideas.

For example, maybe he really could have been Prime Minister. Maybe the New Party could’ve really fulfilled its potential. Or maybe he could’ve stayed within the Labour Party and somehow deposed and replaced Ramsay McDonald.

Equally, it’s easy to imagine a version of history where the Nazis succeeded in conquering Britain. A version of history where Hitler annointed Mosley leader of a fascist UK.

But, while it’s easy to imagine a version of Oswald Mosley’s life where he amounted to something, that wasn’t the life he led.

Instead, the historic Mosley will always remain a man who gambled big and lost everything. A man who started out sympathetic, but eventually drifted away into a fog of conspiracy theories and antisemitism that put him beyond the pale of all but the craziest of British Nazis.

In the end, perhaps that’s a fitting epitaph for a man so full of self-importance. To be remembered not with awe, not with fear, but with mild curiosity: an interesting failure at best.

It’s comforting to know that, were Mosley alive today, this reputation is probably exactly what he wouldn’t have wanted.

Sources:

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (paywall – although accessible with a UK library card): https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-31477

Observer review of Mosley bio: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2006/apr/23/biography.features1

Holocaust Research Project: http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/holoprelude/mosley.html

Olympia Rally background: https://hatfulofhistory.wordpress.com/2018/09/09/from-olympia-to-hyde-park-british-anti-fascism-in-the-summer-of-1934/

New Statesman, Memories of Mosley: https://www.newstatesman.com/archive/2013/08/oswald-mosley-memories-unrepentant-fascist

BBC: Who was Oswald Mosley? https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-49405924

Diana Mosley bio: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-92691

British Union of Fascists: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-96364

Battle of Cable Street: https://time.com/4516276/cable-street-battle-london-east-end-80-years/

Battle of Cable Street, background: http://www.cablestreet.uk/