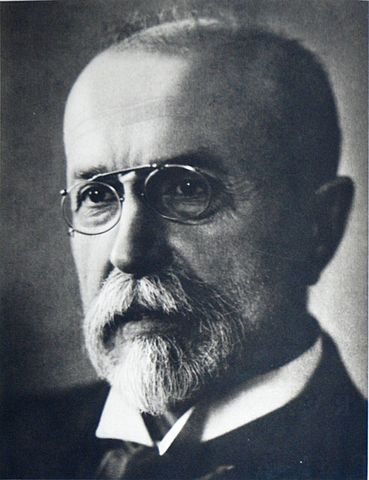

He’s one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th Century. Born a small-town nobody in the Austrian Empire, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk nonetheless wound up rising to the very top of Central European politics. An academic and philosopher, he made his name defending the rights of the downtrodden, from Jews falsely accused of ritual killings, to Slav separatists. But it would be what he did during WWI that cemented his reputation. Part Czech and part Slovak, Masaryk dared to envisage a homeland for both ethnicities. When the Austro-Hungarian Empire disintegrated in 1918, it was from his blueprint that Czechoslovakia was born.

Yet Masaryk was more than just the founder of the Czechoslovak Republic. It’s first and longest-serving president, he helped steer this brand new nation through one of the darkest times in modern history. Leading by example, he tried to create a liberal, rational democracy amid a sea of dictatorships… only to live long enough to see his homeland begin to crumble before the awesome might of Nazi Germany. Both a European George Washington, and a modern-day philosopher king, this is the life of Tomáš Masaryk: the father of Czechoslovakia.

Humble Beginnings

It was a cool March day when Tomáš Jan Masaryk was born in 1850, outside modern-day Hodonín in the Czech Republic. Not that there was anything remotely like the Czech Republic in existence back then. In the mid-19th Century, Central Europe was dominated by the Austrian Empire. Under the Habsburgs, the monarchy had ruled all Czech-speaking lands for centuries.

Until recently, this had just been the way things were. But two years before Masaryk’s birth, something had happened that would profoundly shape the course of his life.

1848 had been Europe’s year of revolution.

Across the continent, pissed-off liberals had risen up against kings and emperors, igniting political fires from France, to Prussia, to Hungary. In Bohemia, the Czech historian František Palacký had called a revolutionary Slavic Congress, determined to win autonomy for all Slavs in the Austrian Empire.

Unfortunately, the Austrians had responded by bombing Prague to bits, and that had been that.

Well, almost.

The truth was, once nationalism was out of its box – once those Czech dreams had been given form – it was impossible to put back in. It would take another seven decades, but the hopes of the 1848 revolutionaries would one day be fulfilled.

And it would all be thanks to Tomáš Masaryk.

Not that there was anything in his childhood to indicate the boy would grow up to be so important.

Masaryk’s father was a salt of the earth Slovak coachman working on an imperial estate; while his Czech mother had assimilated with the dominant Austrian culture. The family were also relatively poor; enough so that Masaryk’s parents felt they couldn’t afford to send their son to secondary education.

It was only thanks to outside intervention that Masaryk didn’t spend the rest of his life in obscurity.

From the earliest age, the boy had been a prodigious devourer of books.

Like, if books were a breakfast buffet, Masaryk would be the huge American in cargo shorts going back for his seventeenth serving of bacon. He read everything he could get his hands on, retaining knowledge on hyper-obscure subjects.

Eventually, the Dean of his local school couldn’t take it any longer. He went to Mr. and Mrs. Masaryk and basically said “my dudes, I know you’re poor, but you have to give this boy an education.”

And so it was that young Masaryk found himself ditching his locksmith apprenticeship, and enrolling in Brno’s Catholic grammar school.

The move was a lifesaver.

At school, Masaryk proved so adept he won a scholarship.

However, this still wasn’t enough to fund his studies, so he took up tutoring work for the family of Anton Le Monnier, the Director of the Police.

This would turn out to be extremely lucky.

In 1868, the Catholic-raised Masaryk started refusing confession. Not a big deal, you might think, but the grammar school considered it a requirement. When Masaryk kept refusing, they kicked him out. And, just like that, Masaryk’s time in education could’ve been over.

Had it not been for Le Monnier.

When the policeman found out about the suspension, he was all like:

“Hey, that’s weird! I’m about to move to Vienna to become a super-important police guy. Wanna come with?”

That’s how, in 1869, Tomáš Masaryk found himself living in the imperial capital.

Life wasn’t easy, even with Le Monnier as a patron. Masaryk worked his prdel off tutoring the family and passing his exams. But pass he did, enrolling in 1872 at Vienna’s Philosophical Faculty. This was a huge step for the son of a semi-illiterate Slovak coachman, but it almost all fell apart.

In 1873, Le Monnier died, and Masaryk was suddenly without a guardian angel.

It was only through sheer luck that he managed to find another wealthy family to take him in, and keep our video from fizzling out right here. Finally, in 1876, Masaryk graduated. He moved to Leipzig, hoping to do some studying. But it wouldn’t be books that occupied his mind.

It would be while in Germany that Masaryk met the woman who would change his life.

The Times are a-Changin’

If you were to compile a list of the most-intense periods of Masaryk’s life, the summer of 1877 would certainly have to make the top three. That’s because, over the space of just two months in Leipzig, Masaryk met, fell in love with, and got engaged to the woman he’d be with for the rest of his life.

Charlotte Garrigue was a wealthy expatriate from New York, whose determined progressivism was like a grenade dropped into stuffy Central Europe. A philosopher and feminist, she and Masaryk bonded over a love of John Stuart Mill – particularly his landmark essay On the Subjection of Women.

You know how you occasionally meet someone you feel you can talk about anything with? A person who just gets you?

Well, that was Masaryk and Garrigue. When Masaryk also managed to save Garrigue from drowning during a river trip, it was just the sexy icing on the cake of love.

And yes, you can be certain I’m never using that particular metaphor ever again.

Engaged shortly after, the original plan was for both of them to go back to their respective homes so Masaryk could find a job. But when Garrigue was taken ill in America, Masaryk abandoned Vienna to be by her side.

The two married in New York City on March 15, 1878.

The only bum note was Masaryk committing the faux pas of asking his new father in law for money – which went over about as well as calling him a stupid Yank and kicking him in the balls. But, when it became clear that Masaryk was, like, literally broke, Dad consented to keep the new family afloat.

Finances semi-secure, Masaryk and Charlotte returned to Europe. Then it was three solid years of awkward handouts from Dad, until Masaryk finally landed a professorship at Prague University.

The family moved to the great Bohemian city in 1882, just as everything was changing.

The romantic nationalism of 1848 hadn’t gone away in Prague. Instead, as more Czechs flooded in from the surrounding countryside, it had reached a fever pitch. Masaryk joined the university just as it was being divided into separate Czech and German institutes. While he did get swept up in the wave of feeling – writing a treatise on Mister 1848 himself, František Palacký – he wasn’t some mindless nationalist.

In the 1880s, a key pillar of the Czech revival was a pair of recently-rediscovered epic poems from the medieval era, written in old Czech.

Considered the Bohemian equivalent of the German Nibelungenlied, they were a source of intense nationalist pride.

They were also as fake as a doctored image of George Washington taking part in Wrestlemania, something Masaryk proved with some deft literary analysis.

Naturally, all the Czech nationalists hated him.

It’s here that we see one of the most-admirable things about Masaryk.

Although he had his own romantic ideals, he was a man who believed first and foremost in being rigorous in his beliefs, even when it made him unpopular.

As he supposedly once said:

“The glory of a nation cannot be built on counterfeits.”

Nor is this the only example of Masaryk being willing to swim against the tide. Years later, in 1899, he would publicly agitate for the retrial of Leopold Hilsner, a Jewish man convicted on nonexistent evidence of ritual murder. At this time, anti-Semitism was rife among Czech nationalists. When Masaryk came out on Hilsner’s side, he was pelted with stones and spat on in the street.

At the university, nationalist Czech students hounded him until he was forced to go on unpaid, extended leave.

It was a high price to pay for his commitment to rationality. But it did have one unexpected good side.

It’d be weathering these storms that gave Masaryk the steel backbone he’d soon need to change the world.

Politics and War

It was amid one of his periodic controversies that Masaryk began to turn away from academia, and towards politics. He began writing articles, agitating for a revival of the dreams of 1848, dreams focused on winning Czech autonomy within Austro-Hungary.

Not that he only focused on Czechs. One of his sharpest articles was a demolition of how the Hungarian half of the empire treated its Slovak minority.

In no time at all, Masaryk had established himself as a heavyweight Czech thinker.

So when the liberal Young Czechs party approached him about running in the 1891 elections, it seemed like a no-brainer. Masaryk took them up, was duly elected, and found himself back in Vienna for the first time in years.

What he saw there didn’t fill him with confidence.

In Austria’s Reichsrat, the Young Czechs harped on a course of uncritical nationalism, unwilling to work within the system so much as just shout at it. In 1893, Masaryk quit in disgust, certain this lack of realism was what was keeping the Czechs from making any advances.

For the next couple of years, he hung around the edges of the Prague political scene, writing books and churning out articles.

By 1900, though, he’d decided to put his money where his mouth was.

That year, Masaryk founded his own Realist Party, with the aim of achieving Czech autonomy in, as the name might imply, a realistic way.

Although the party wasn’t a bust, it also wasn’t a major successes.

En Marche! in 2017 this was not. Although it succeeded in returning Masaryk to the Reichsrat in 1907, it was a minor force at best, one among many Czech parties. It probably didn’t help that the nationalists still couldn’t agree on what they wanted: an autonomous province within Austria, or a wholly independent state?

But while Masaryk was firmly in the autonomy camp, that would soon change.

Masaryk’s transformation from realist to “world-changing visionary” began on 28 June, 1914.

That day, a radical Bosnian-Serb assassinated the heir to the Austrian throne, triggering a series of crises that quickly led to the gigantic crisis called World War One. For years, Masaryk had been condemning both Austria’s meddling in the Balkans, and its alliance with Germany.

Now, he watched in horror as both of these things dragged the entire continent toward unprecedented bloodshed.

By Christmas, Masaryk had had enough.

Now convinced of the need for a separate Czech nation, he headed off into voluntary exile.

There, amid the ancient cities of a Europe on fire, Masaryk began a PR drive designed to make the Allies recognize Czech independence.

It was an insane task.

Masaryk had friends in academia across the world, but he wasn’t exactly famous. He wasn’t yet Masaryk the statesman. He was Masaryk the lonely dude, timidly knocking at the doors of power with a bonkers request.

Well, maybe “lonely” is a bit unfair.

In 1915, while in France, Masaryk was joined by another future president of Czechoslovakia, Edvard Beneš.

Together – and with help from Masaryk’s literary friends – they managed to get themselves before the Allied leaders long enough to be officially recognized as the Czech Liberation Movement. It was an important first step, an acknowledgement that they weren’t just two random dudes farting around Europe, but guys with a proper – if minor – role.

Now all they had to do was turn that minor role into the liberation of their entire country.

It couldn’t be that hard… could it?

The President Returns

The next few years played out like a globetrotting thriller. Masaryk moved across Europe, bouncing from France, to Britain, to Russia, always agitating for Czech and Slovak unity in a new state.

Yep Czech and Slovak. In 1915, exiles from both communities had started making plans for a federation, and Masaryk had picked that ball up and just run with it.

And it really was running.

Masaryk was convinced Austrian agents were trying to assassinate him as he hopped around Europe, and had even told Beneš to use his death for propaganda should he be killed. Speaking of propaganda, Masaryk was a deft hand at it, making sure articles sympathetic to the Czech cause appeared daily in Allied newspapers.

When the Tsar was overthrown in 1917, he even traveled to Russia to organize former Czech and Slovak POWs into a fierce fighting unit. These Czechoslovak Legionnaires would run rampant in Russia for years, at one point even controlling the Trans-Siberian Railway.

And so it went: Masaryk zooming around the globe, shoring up support for Czechoslovak independence.

With each new destination, his fame grew. With each new PR stunt, a few more came over to the cause.

But it would be in the US that Masaryk met his greatest convert.

Woodrow Wilson was almost the perfect match for Masaryk’s left-leaning, independence-minded politics. At the head of America’s Czech and Slovak groups, Masaryk impressed his cause onto the 28th President. It clearly worked.

On January 8, 1918, Wilson listed his Fourteen Points, including the complete dismemberment of Austria-Hungary. A couple of months later, the Lansing Declaration explicitly gave US backing to an independent Czechoslovakia.

From here on out, events took on an air of inevitability.

In May, Masaryk met with Slovak representatives in Pittsburgh, where the two sides struck an agreement on Slovak autonomy within the new state. In June, the Allies declared the still non-existent Czechoslovakia an Allied power, and recognized the borders proposed by Masaryk.

But, despite the feeling in the air, there was nothing inevitable about any of this.

Historical events feel inevitable because we’re looking back on them, as if they were as unchangeable then as they are now. But the reality is that none of this was set. Austria-Hungary could’ve easily survived the war intact. Or maybe the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia could’ve broken off, but left the Slovaks a persecuted minority in Hungary.

The fact Czechoslovakia ever existed is down almost entirely to Masaryk’s tireless work.

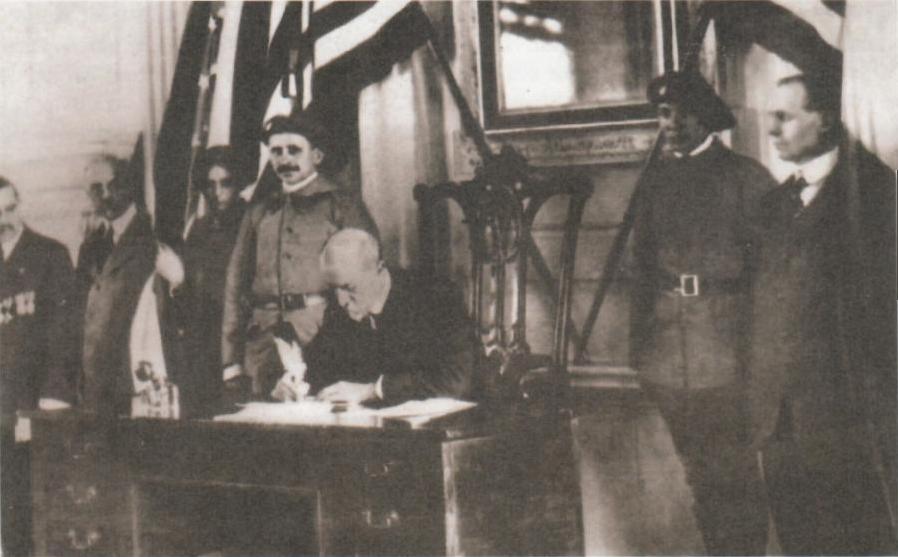

Finally, on October 28, 1918, this new nation officially broke off from the collapsing empire.

By now, Masaryk had already been named president of the interim government, and hastily made arrangements to return to Prague. His original plan was to meet in a cafe with some old friends and celebrate their new Republic.

But, as he got closer to Europe, it became clear he wasn’t returning to his cosy old life. Wasn’t even returning as TG Masaryk, the new interim president.

He was returning as the father of an entire nation.

On December 21, Masaryk arrived to vast crowds desperate to catch a glimpse of him.

The next day, he stood at Prague Castle and proudly declared:

“The affairs of your government are returned into your hands once more, oh Czech people!”

And therein lay the problem.

Masaryk may have left Prague a Czech nationalist, but he’d returned leader of a country in which Czechs just barely made up a majority. In this brave new land, a sixth of the population was Slovak, almost a quarter German, and there were significant minorities of Hungarians, Poles, and Ruthenians.

If Masaryk wanted to make Czechoslovakia work, he was going to have to convince all these wildly different groups that the government spoke for them.

Spoiler alert: he would never quite succeed.

The First Republic

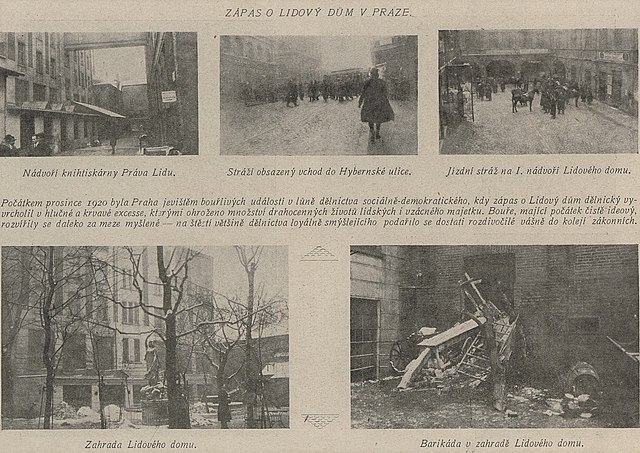

The seeds of Czechoslovakia’s undoing were sown almost the moment it was created. In February of 1920, a Constitutional Assembly was called to determine the shape of this new state, but only Czechs and Slovaks were invited.

That left a third of the nation’s citizens without any say in how their country would be run.

Where the Germans were concerned, this would soon turn out to be a massive problem.

We did a whole video on the Sudeten Germans over on Geographics if you want to learn more, but the basic version is that Germans had been living in Bohemia and Moravia for centuries. As an ethnic group, they were far more-numerous than the Slovaks, and had no interest in taking part in a state run specifically for their Slavic neighbors.

No, they wanted the same freedoms Masaryk had fought for and won from the Austrians. The right to seceed and control their own destiny.

But now the shoe was on the other foot, Masaryk was suddenly all like “Nope!”

Nor was it just the Germans who were unhappy.

In America, Masaryk had promised the Slovaks something akin to home rule. Indeed, he personally envisaged a Swiss-style system, with each group basically left to do their own thing. But the reality of leading a brand-new, unstable state soon destroyed this idealism.

As the 1920s crept onwards, power was centralized more and more in Prague, and more and more in the hands of Masaryk.

Although he wielded no formal power as president, Masaryk had a big enough reputation, enough charm, and enough allies in politics and the media to get his way on most issues.

The result was something known as Castle Politics, with a small clique centered around Masaryk effectively ruling outside parliament. No matter how often Masaryk made speeches promising a federal system in the future, the reality was that Czechoslovakia was becoming a highly-centralized oligarchy.

Yet, if it really was an oligarchy, it was a fundamentally liberal one.

A die hard liberal at heart, Masaryk genuinely believed in respecting the rights of all his subjects; even separatists like the Sudeten Germans or Hugarians. The constitution guaranteed their freedom of speech, language, worship, and assembly. A repressive place, this was not.

Masaryk also went out of his way to try and mollify the unhappier ethnicities.

A 1925 pact signed with Germany to recognize one another’s borders as legitimate went a long way towards getting the Sudeten Germans onside.

In fact, by the time Masaryk was reelected in 1927, there was good reason to be hopeful.

The economy was booming, a massive road and rail building plan was keeping people in work, and a treaty had been reached with France to offer the Republic a security guarantee. On the tenth anniversary of Czechoslovakia’s foundation, Masaryk even felt comfortable enough to declare:

“We began with empty hands, without an army, without constitutional traditions, with a rapidly falling currency, in the midst of economic chaos (…) And yet we have stood the test and acquitted ourselves with honour.”

There was optimism in the air. A feeling that things were bumpy now, but with time and a little luck they’d smooth out, and Czechoslovakia would take its rightful place among the great democracies.

Unfortunately, time and luck were both things in short supply.

In 1928, Masaryk suffered a massive heart attack.

Although he survived, the shock to his system left him a physical wreck, weak and broken. It was the perfect metaphor for what was about to happen to both Czechoslovakia, and the entire world. As the end of the decade came into view, a massive shock was approaching. One that would leave Central Europe desperately sick.

It was this sickness – a terrible, poisonous sickness called fascism – that would finally kill Masaryk’s young country.

Collapse

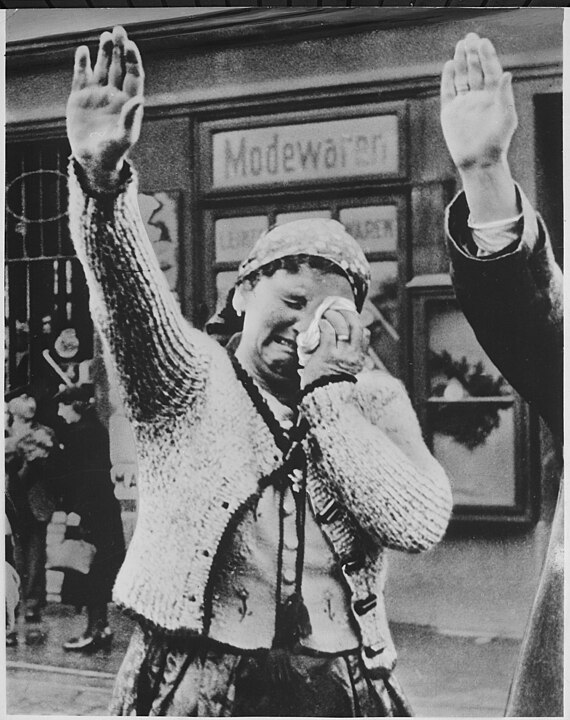

On October 29, 1929, Wall Street fell to Earth with a crash heard around the globe. It was the start of the Great Depression, of a decade of misery, unemployment and endless, gnawing hunger. In Czechoslovakia, it blew through industrial cities like a bitter wind, shuttering towns, leaving millions destitute.

Unfortunately, most of the worst-hit cities were in the Sudetenland.

As Prague launched a modest relief program, the Sudeten Germans watched as their livelihoods were destroyed. Undoubtedly, Czechs and Slovaks suffered in the Depression. But reality isn’t what matters. What matters is that the German minority began to feel like Masaryk and his circle didn’t care about them. That Prague was looking out only for Slavs, and leaving the Germans to suffer.

So when a silly little man with a funny moustache took power in Germany proper, promising to make the Germans great again…

Well, it isn’t hard to see how the Sudeten Germans’ dreams of secession might come roaring back. The rise of the Sudeten fascist party under Hitler-fanboy Konrad Henlein coincided with a deterioration in Masaryk’s health.

Although he was reelected again in 1934, it was mainly because no other viable candidates existed.

Masaryk had succeeded in identifying himself with the state so much that nobody could conceive of a time without him.

But that time was almost upon them.

In May of 1935, Parliamentary elections returned 44 seats for Henlein’s fascists, a single seat less than the largest party. With over two thirds of all Sudeten Germans now backing a secessionist party, it was clear Czechoslovakia wasn’t going to hold together much longer.

Masaryk, though, wouldn’t live to see the bitter end.

On December 14, 1935, Masaryk abruptly resigned, passing the presidency to his old buddy, Edvard Beneš. Then the father of the nation slipped away into retirement to await the inevitable. For nearly two more years, Masaryk clung onto life. Clung on just as Czechoslovakia did, even as the sickness grew inside it.

So many people came to inquire about his health that assistants started hanging posters on the gate every morning, giving updates on the situation.

Finally, on September 14, 1937, came the poster bearing the worst update of all.

TG Masaryk died that day, aged 87.

When his funeral was held a week later, it lasted nine whole hours, such was the volume of people who wanted to pay tribute. Almost exactly a year after Masaryk was buried, France, Britain, Italy and Germany signed the Munich Agreement, allowing Hitler to annex the Sudetenland.

It was the beginning of a painful death for Czechoslovakia.

Its border regions lost to Germany, the young country was forced to simply lie there as first Poland and then Hungary tore yet more chunks out of it, leaving a weak rump state barely clinging to life. In March of 1939, Germany delivered the fatal blow. Bohemia and Moravia were occupied, while Slovakia was split off into a separate state under a fascist puppet government.

Yet the story didn’t end there.

Despite its rocky life, the Czechoslovak Republic established by Masaryk proved durable enough that – when WWII finally ended – it didn’t stay broken and partitioned; but was resurrected nearly whole. The new Czechoslovakia then lasted another 48 years, surviving a Communist takeover and decades of dictatorship, before peacefully separating into modern-day Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993.

But what of Tomáš Masaryk himself?

Well, he’s still regarded as a hero in many places, not least here in Prague, and it’s not hard to see why.

Here was a man who didn’t just lead his nation, but was the sole reason for its existence.

Before Masaryk, the idea of an independent Czech and Slovak nation away from Austria’s chilly embrace had been a pipe dream. It was he who took that dream and forced it into reality, shaping the future through the sheer force of his vision.

And that vision is why Masaryk is still important.

As someone unafraid to stand up for the truth, for the downtrodden, Masaryk brought a sorely needed humanism to politics, one reflected in the tolerant state he built. Sure, he may not have truly achieved it, but he never lost sight of his goal: to build a nation in which all ethnicities could live the best lives they could.

His name may be obscure compared to some of his contemporaries, but there’s no doubt that Masaryk helped shape not just Central Europe’s past, but also its present.

The man himself may be long gone, but his dream lives on.

Sources:

Talks with TG Masaryk, Karel Capek: https://www.amazon.com/Talks-T-Masaryk-Karel-Capek/dp/0945774265

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Tomas-Masaryk

Biography from the Czech President’s Office: https://www.hrad.cz/en/president-of-the-cr/former-presidents/tomas-garrigue-masaryk/curriculum-vitae

Encyclopedia of World Biography: https://biography.yourdictionary.com/toma-x0161-garrigue-masaryk

Radio Prague: https://english.radio.cz/tomas-garrigue-masaryk-8070822

Biography during WWI: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/masaryk_tomas_garrigue

Biography of Charlotte: https://translate.google.com/translate?hl=&sl=cs&tl=en&u=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.idnes.cz%2Fzpravy%2Fdomaci%2Fcharlotta-masarykova-americanka-ktera-milovala-prahu.A080125_150407_zajimavosti_adb

Britannica, Czechoslovak history: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Czechoslovak-history

Masaryk and feminism: https://www.radio.cz/special-podcasts/podcast/the-feminist-legacy-of-charlotte-and-tomas-garrigue-masaryk/

Some extracts on democracy: https://english.radio.cz/tomas-garrigue-masaryk-seeing-and-listening-jungles-our-human-society-8106275

Prague travel biography, a bit one-sided: https://www.private-prague-guide.com/article/tomas-garrigue-masaryk/

Geographics on Sudetenland: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prJaWk7ZGT0

Slav Congress: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Slav-Congress

Hilsner Affair: https://yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Hilsner_Affair

Ten year speech: https://photos.state.gov/libraries/czech-republic/119398/Documents/Masaryk_Speech_1928.pdf

Masaryk’s treatment of anti-Semitism: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/czechoslovakia