When the body of a man was found on a beach in Australia over 70 years ago, nobody yet knew that the investigation that would follow would turn it into one of the country’s greatest mysteries, as even today, we cannot say anything with certainty about what happened on that occasion. Who that man was, how he ended up on that beach, who killed him and, indeed, if he was even murdered are questions still waiting for an answer. Was he a spurned lover who decided to end it all or was he actually an international spy who was assassinated?

With inexplicable twists and turns usually found in the pages of a good thriller novel, this investigation became known worldwide as the Mystery of the Somerton Man or the Tamám Shud case. Today we’ll be taking an in-depth look at a real-life whodunnit which will include untraceable poisons, hidden messages, encrypted codes, rare books, secret love affairs, and, of course, a cold-blooded murder.

The Discovery

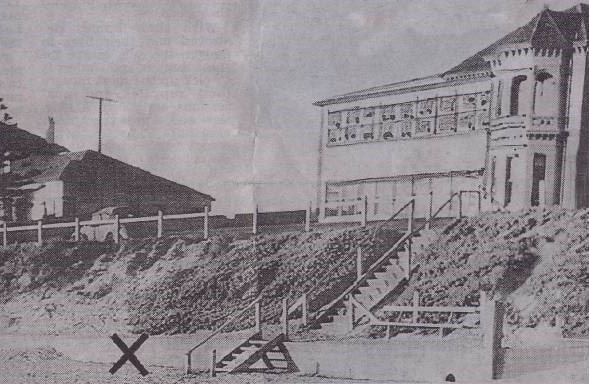

It all started on the morning of December 1, 1948, on the Somerton Park beach in Adelaide, Australia. Police had arrived at the scene after receiving a call about the body of a middle-aged man lying in the sand, halfway propped up against a sea wall. Two horseback riders were the ones who had made the grisly discovery at around 6 a.m. and alerted the authorities after going in for a closer look to make sure that the man was, indeed, dead.

Police found him to be in his early 40s, smartly-dressed, wearing a clean suit and a polished pair of nice shoes. He had a bus ticket in his pockets which he had purchased the day before, indicating that he had not been present in Somerton earlier than the previous afternoon. He also had an unused second-class railway ticket to a nearby suburb named Henley Beach, an aluminum comb, a half-empty pack of chewing gum, a box of matches, and, strangest of all, a pack of Army Club brand cigarettes which actually contained cigarettes from a different brand called Kensitas.

A talk with the neighbors revealed that they had seen a man sitting in that same spot the night before, but they all assumed that he was either sleeping or drunk and left him alone. One couple who claimed they saw him at around 7 p.m. while out for a stroll said that, at one point, the man extended one arm upward, before letting it fall limp again. Afterwards he remained perfectly still, even though there were many mosquitoes buzzing around his face. Another couple saw him later and, while they thought it bizarre that the stranger was dressed in a suit at the beach, they also did not go in closer to investigate. There were no obvious signs of violence, so investigators initially concluded that the man became ill, sat down and propped himself up against the wall for a rest, fell asleep or passed out and died during the night. It was unusual, but hardly had the makings for one of the country’s greatest mysteries. But then, the autopsy happened and things started to get weird.

First, pathologist John Barkley Bennett concluded that the mysterious stranger died no earlier than 2 a.m., which means that he was still alive when everybody saw him the previous night, although he had been clearly incapacitated somehow. The doctor agreed that the dead man was somewhere between 40 and 45 years old, and that there were no signs of violence on his body. In fact, he had been in great physical condition – his body was fit and his heart was healthy, even though it was heart failure which actually killed him.

This was a bit counterintuitive to someone who dropped dead on the beach, so the pathologist started to suspect that foul play might have been involved. He looked for signs of poisoning and he found them – the pupils were small and unusual, the spleen was around three times the normal size, and the liver, the kidneys, and the stomach were all filled with congested blood. Moreover, being poisoned would also have explained the stranger’s behavior from the previous night, where he had seemingly been alive, yet unable to move or communicate with anyone apart from a single arm spasm.

It was starting to look like a clear case of poisoning, although whether the man took that poison willingly or not was still inconclusive. Anyway, to be sure, the pathologist sent samples to a chemistry lab to check for toxins. Which they did…and they found nothing. No cyanides, no alkaloids, no phenols, no barbiturates. Not a trace of any of them. Later during the investigation, an eminent pharmacologist named Sir Cedric Stanton Hicks indicated that a very potent poison was likely used which decomposed soon after death and left no trace. He suggested strophanthin or digitalis, although whether he was right or not became impossible to prove. In the end, even though the pathologist was convinced that the death could not have been natural, he could not reach a conclusion regarding the cause of death.

Meanwhile, the police were trying to identify the body which the media had taken to calling the “Somerton Man,” but they had little to go on. There was no wallet with the body and, in fact, there was no form of identification at all. His dental records could not be matched to any known person and even the labels on his clothes had been removed. His fingerprints were not found in any Australian database, and even reaching out to international help in Britain and the United States yielded no results. His photograph was circulated throughout the entire country, and even though dozens of people came to view the body, nobody ultimately recognized him.

The only minor lead that could possibly help with identification were a few unusual physical traits discovered during the autopsy. The Somerton Man had very smooth and soft hands, showing no signs of manual labor, but he had extremely well-developed calf muscles, the most pronounced that the pathologist had ever seen. His toes were also wedge-shaped, indicating that the victim often wore pointed shoes with high heels. These facts together suggested that maybe the Somerton Man had been a ballet dancer, or a long-distance runner.

The Suitcase

By the start of the new year, the police had exhausted all their leads and the Somerton Man was still a ghost. Some still argued that his death had been a suicide, but why would someone develop such a complex method of taking their own lives? And more to the point, how could they do so? They would have to first be able to get their hands on a potent poison that could not be traced back to them, then somehow erase all records of their existence and make sure that nobody came forward to identify them.

In January, authorities had widened their investigation to the point where they began examining all discarded or lost luggage found in Adelaide hotels and railway stations, in the hopes that one of them might have belonged to their victim. It seemed like an act of desperation, but it produced results. On January 14, staff from the Adelaide Railway Station came forward with a suitcase that had been sitting in their cloakroom since the morning of November 30. The timing lined up nicely as the previous evidence, scant as it was, also suggested that that was the day the Somerton Man arrived in Adelaide, but there was nothing conclusive to connect the two together.

Even so, police took what they could get. The suitcase pretty much contained what you would expect a traveling man to have with him: multiple items of clothing, a shaving kit, shoe polish, toothbrush and toothpaste, a table knife, a pair of scissors, some pencils, some handkerchiefs, and a lighter.

The only slightly unusual items in the suitcase were a stenciling brush typically used for stenciling cargo on merchant ships and a sewing kit containing a Barbour brand orange waxed thread that was not available in Australia at the time. One other small clue was the stitchwork on a coat found in the suitcase which was unknown in Australia, but was commonly used in America. These signs pointed to the possibility that the Somerton Man may have traveled to the United States at one point or may have even worked as a sailor.

Like before, all labels and other identifying markers had been painstakingly removed from the clothing, except for three tags with the name “T. Keane” on them. This lead proved to be another dead end, though, as nobody was missing by that name. In the end, police concluded that whoever removed all the other labels left the ones with “Keane” on them because they knew it would lead nowhere.

The Note

If you thought this case was confusing up until this point, don’t worry, because it got a lot more mysterious in June of 1949 when a new clue veered the investigation from “unsolved murder” into “spy thriller” territory. A new scientist was brought in to lend his expertise – pathology professor Sir John Burton Cleland – in the hopes that he might spot something that everybody else missed.

He drew a few conclusions regarding the evidence that had already been analyzed. For example, we mentioned that the Somerton Man wore nice looking shoes, but the truth is that they were not simply “nice,” they were spotless, and did not look like the shoes of a man who walked on the beach. There was also no vomit on the clothes or in the area where the victim was found, which is unusual seeing as vomiting is the main physical reaction to poison. This made Cleland suspect that the man had been poisoned elsewhere and dumped on the beach, incapacitated but still alive. In the end, Cleland felt pretty confident that the Somerton Man died from poison, but he, too, admitted defeat when it came to establishing cause of death.

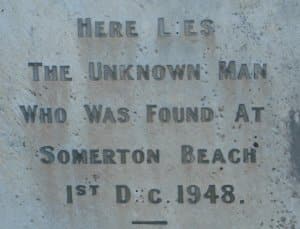

After Cleland was finished with his investigation, it was time to actually bury the victim as the body had started to decompose. Even so, authorities knew that they might have been getting rid of one of their key pieces of evidence, so they took the unusual precautions of embalming the Somerton Man first, then having plaster casts made of his head and torso. Finally, he was buried under concrete, in dry ground, to make it easier to exhume him should the need arise.

This second, more thorough examination of the victim’s clothing did yield a new, strange, and unique piece of evidence. Inside his trouser pocket had been sewn a smaller fob pocket for a watch. Inside that pocket was a rolled-up piece of paper with two words printed on it – “Tamám Shud.” In Persian, this meant “finished” or “ended,” and the murder itself often became identified as the “Tamám Shud case.”

Because the words were written in such a distinctive script, a local police reporter with the Adelaide Advertiser named Frank Kennedy actually recognized where they came from – a book of 12th century Persian poems called The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, the so-called “Astronomer-Poet of Persia.” You might think this is incredibly obscure and archaic, but the truth is that the poems of Omar Khayyam were pretty well-known and popular in the English-speaking world at the time, following an 1859 translation by English writer Edward FitzGerald.

This new evidence made some investigators hop on the “suicide” bandwagon again. “Tamám Shud” were the last words in the poetry book, and the poem itself was all about living life to the fullest and having no regrets when it was time to die. The symbolism certainly suggested a person taking their own life but, of course, it also could have easily been staged by someone trying to make it look like suicide. In other words, just like up until this point, police still knew nothing for certain.

The Book

The meaning of the words “Tamám Shud” aside, police became interested in the actual book where they came from. If they could somehow find that particular copy, maybe they could trace it back to the source where it was bought or borrowed from which, in turn, could provide some new clues as to the identity of the person who took it.

They started rummaging through all the bookshops and libraries in Adelaide and nearby towns, but struck out. Then they put out a public appeal, showing the distinctive script that the words were written in, and hoped to get lucky. Which they did. On July 22, 1949, a man only identified under the pseudonym “Ronald Francis” came forward with a copy of The Rubaiyat which he saw in the glovebox of his brother-in-law’s car. When he asked his relative about it, Francis said that somebody threw the book inside the car’s backseat through an open window on November 30, while it was parked one block away from Somerton Beach. All signs pointed to this copy of the poetry book being the one where the scrap of paper came from, and then the police lined up the torn piece to the page from the book and they matched up perfectly.

![As quoted in the Smithsonian article regarding the two printed words shown: "The scrap of paper discovered in a concealed pocket in the dead man's trousers. 'Tamám shud' is a Persian phrase; it means 'It is ended.' The words had been torn from a rare New Zealand edition of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam." [dating to the 12th century]](https://biographics.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Actual-tamam-shud.jpg)

There was, of course, the other possibility that the copy did not belong to the Somerton Man and that his killer was, in fact, the one who put the torn up paper in his trouser pocket and who also threw the book in the back of the car of Ronald Francis’s brother-in-law. Even so, some of the same questions still applied. Why use such a valuable book and why didn’t anybody report that they sold or lost a copy? What investigators inferred was that, for whatever reason, it had to be this specific edition, which the owner probably brought with them from someplace else so it could not be traced.

This idea was given credence by two important clues found inside the book. One was a phone number penciled on the back cover. The other clue was markings of writing which had been scribbled on something which had been placed on top of the book and left behind faint indentations. They were five lines of seemingly random letters, of which one line had been crossed out. Immediately, investigators believed they represented some kind of secret code, which could have also potentially explained why the book had to be the original 1859 version. The translations varied between different editions so, if the message was hidden inside the text of the book, the code might not have worked with any other edition.

Like all the other clues, this sounds plausible, but can only remain speculation because the code has never been cracked, so what about the other lead – the phone number? It was unlisted, but police tracked it down to the house of a young woman who lived very close to Somerton Beach. During the investigation, her name was kept private so she was always referred to by the nickname “Jestyn” or the pseudonym “Teresa Johnson.” It was only in recent years that her true identity was disclosed with her family’s permission – she was Jessica Thomson, at the time a 27-year-old nurse who was married to a man named Prosper Thomson.

She agreed to cooperate with the investigation, as long as her name was kept out of it. She went down to the morgue. She couldn’t see the body anymore, because it had been buried, but she did look at the plaster casts taken of his head. Investigators noted her reaction as being odd, as Thomson was completely taken aback and appeared as she was about to faint. Given that she had been a nurse during the war, Thomson had surely seen a lot worse than the plaster cast of a dead body so, unsurprisingly, investigators believed her reaction was caused by a close connection she had with the deceased. Even so, Thomson then denied knowing who he was. As far as the book was concerned, she admitted that she once had a copy, which she gave to a soldier named Alfred Boxall in Sydney during the war. She did not go into specifics as to the nature of their relationship, although investigators obviously suspected a love affair.

For a brief moment, police hoped that this would finally bring the case to an end. It was a tale as old as time, they thought, as Boxall was the jilted lover who decided to take his own life after visiting the woman he loved one last time. There was just a tiny snag in their hypothesis, however, as they soon discovered that Alfred Boxall was alive and well, and working as a bus maintenance officer in Randwick. Not only that, but he still had his copy of The Rubaiyat, complete with the words “Tamam Shud,” and it didn’t even turn out to be the 1859 edition, anyway. So that idea went out the window.

The Theories

The dead end on the Boxall theory pretty much extinguished the last glimmer of hope that investigators had of solving this case. They had pursued all the leads and each and every one of them left the police more confused and uncertain than before.

The lack of concrete facts in this case led to the appearance of rumors and hypotheses to fill the void and one idea that still has a lot of support is that the Somerton Man had been a spy. It would explain a lot of the unusual aspects of the case – the intricate death, the untraceable poison, the book and the code. Some people even believe that Jessica Thomson had also been a spy, and this includes her own daughter, Kate. In an interview, Kate recalled that her mother once made a reference to knowing exactly who the Somerton Man was, but would not go into detail, and on another occasion, Jessica admitted to being fluent in Russian, although she, again, would not say when or why she learned it. Her family members also think it is possible Jessica was having an affair with the Somerton Man, and that her son Robin, who was born a year before the Somerton Man died, was actually his. Jessica Thomson passed away in 2007 so, if she did know more about the Tamam Shud case, she took those secrets to her grave.

But what about today? Surely, with modern technology and forensics, new leads could still be found. Well, there have been a few new developments worthy of mention. First one was in 2011, when an Adelaide woman believed she identified the Somerton Man as a British sailor named H. C. Reynolds. Among her father’s old possessions, she found the ID card of a man identified as Reynolds who served in World War I and bore a striking similarity to the Somerton Man, albeit 30 years younger. She took the photograph to a biological anthropologist who compared the image to photos of the Somerton Man and concluded that the ear shape was very similar, and also found a mole which was in the same location on both men. Others disagree with this identification, claiming that they pieced together the life of the sailor from available records and that the real Reynolds died in 1953.

Another private investigation is being led by Professor Derek Abbott from the University of Adelaide who has been researching the Somerton Man for over a decade. Abbott and his team have approached this case from two angles. One involves cracking the code and the other using DNA to identify the body.

The first isn’t going so well. The team has managed to eliminate numerous types of ciphers, but the most likely scenario is that the code needs the original 1859 poetry book to work, which has since been lost and they have been unable to secure another copy.

The DNA is showing more promise. For years, Abbott has been unsuccessful in his efforts to convince the South Australian Government to exhume the body of the Somerton Man because he couldn’t prove a significant and legitimate reason for it. This changed in 2017 when he recovered a few hairs from the plaster cast made of the Somerton Man decades ago, and was later able to analyze mitochondrial DNA from that sample. Abbott’s latest efforts swayed the current South Australian Attorney General who approved an exhumation order late last year. Obviously, given the current global situation, this has been put on the backburner, but it still is possible that, one day soon, we will discover his true identity and solve the mystery of the Somerton Man.