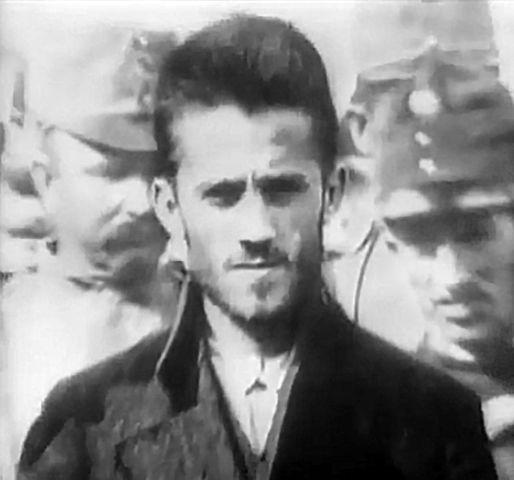

He’s likely the single most-successful assassin in history. When 19-year old Gavrilo Princip fired two shots in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, killing the heir to the Austrian throne, he set in motion events that would change the course of history. A South Slavic nationalist, Princip’s actions would not only result in the creation of a South Slav state – Yugoslavia – but in the fall of empires, and the outbreak of WWI. Forget other assassins like John Wilkes Booth or Lee Harvey Oswald. Compared to Gavrilo Princip, those guys were amateurs.

Yet how much do most of us actually know about the teenager who started WWI? Born to a poor peasant family in the desolate mountains of western Bosnia, Princip seemed destined to leave no mark on history. Sickly, small, and physically weak, his life was a world away from that of the imposing, wealthy, powerful man he killed. Yet it would be the unlikely meeting of these two figures that decided Europe’s destiny. Unknown in life, obscure in death, this is the tale of Gavrilo Princip: the assassin who changed the world.

In the Vukojebina

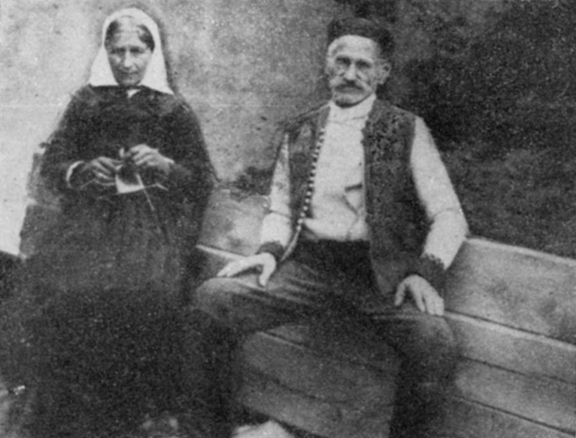

It was the summer of 1894 when Gavrilo Princip was born into a world of utter desolation. His parents’ home village of Obljaj was little more than a hamlet clinging to the side of an unforgiving mountain.

This was remotest Bosnia. A place of stony ground, wild rivers, and bitter nighttime frosts. A place so far from human civilization that locals knew it as Vukojebina – which translates as “the place where wolves go to f–k.”

It was also a place of biting poverty.

The Princips lived in a small house with a dirt floor, upon which Maria Princip gave birth to nine children – only three of whom survived. The boy’s father, Petar, was a part-time mailman and full-time peasant, working backbreaking hours under a feudal system that forced him to give his crops away to remote landlords.

So scant were signs of civilization in this empty land that we don’t even know Gavrilo Princip’s date of birth. The municipal authorities recorded it as June 13, 1894; while the local church entered the month as July. It’s actually something of a miracle that they bothered to register it at all.

Princip was born so weak his father supposedly wrote him off.

The tale goes that it was only when a local Orthodox priest suggested they name the child after the Archangel Gabriel that the boy’s survival became assured.

Whether that’s true or not, it does lead us nicely to a core part of Princip’s background.

Like their entire village, the Princips were from the Orthodox faith.

In Bosnia’s kaleidoscope of ethnicities, that meant they were Bosnian-Serbs; as opposed to Catholic Bosnian-Croats, or Muslim Bosniaks. And just to confuse you some more, Princip being Bosnian-Serb was a whole different deal from him being purely Serbian.

By 1894, the Serbs already had their own, independent kingdom. The Bosnian-Serbs – or any of the Bosnians, for that matter – didn’t.

It would be this fact, more than any other, that would turn young Princip from a peasant’s son into a violent radical.

A History of Violence

OK, so now we’ve established Gavrilo Princip’s background we need to wind back the clock. Just enough to understand the political tensions in play in Bosnia. The twisted path that led to an independent Serbia and a very not-independent Bosnia began back in the 14th Century.

On 28 June, 1389, the expansionist superpower of its day – the Ottoman Empire – defeated the medieval Serbs at the Battle of Kosovo, opening up the Balkans for conquest.

And conquer they did. The Ottomans would eventually conquer all the way to Vienna before running out of steam.

Sadly for Constantinople, all that mega-conquering sent them running smack into the other superpower of the day: the Habsburgs. Rulers of Austria and longtime emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburgs were the Ottomans’ worst nightmare: hardcore Catholics who loved a good, old-fashioned war.

Over the next few centuries, southeast Europe became an eternal battleground, as the Habsburgs slowly pushed the Ottomans back.

For Serbs still smarting over their 1389 defeat at Kosovo, this was all like “Yay. Go Austria!”

But while the Habsburgs spent centuries supporting anti-Ottoman Serbs, it wasn’t because they were good neighbors. In the 19th Century, the Ottoman Empire became known as “the sick man of Europe”, a state so weak, the Serbs were able to gain de-facto independence – although Bosnia continued to smart under Turkish rule.

This change of fortunes hit its peak in 1877.

That year, Serbia and Imperial Russia joined forces to give the Ottomans a gigantic kick up the backside, effectively ending their grip on the Balkans.

It was party time in Belgrade. With the Turks out, Serbia could get started on its plan to build a pan-South Slavic state. One including Bosnia.

It was at this point the Habsburgs made their change from “allies” to “total dicks”.

At the Congress of Berlin, they took Bosnia for themselves.

For the Serbs, this was a little like opening the front door expecting a good friend, only for that friend to immediately seduce your mother.

Belgrade was outraged. They hadn’t just fought a devastating war to see the Austro-Hungarians snatch Bosnia.

But what could tiny Serbia do to stop them?

In August, 1878, Austrian troops marched into Bosnia.

Although the region remained de jure a part of the Ottoman Empire, in reality it became an Austrian colony. On the one hand, this meant stuff like improved roads, the first railways and trams, and electric lighting for Sarajevo.

On the other, it meant merely swapping one distant overlord for another.

The smouldering resentment this entailed would turn Bosnia into a powderkeg. When it finally exploded, it would bring the Austrio-Hungarian Empire crashing down.

Crisis Years

Back in the desolate mountains of Wolf-Sex Land, young Gavrilo Princip was having an utterly average childhood. He helped his parents work the barren land. In his spare time, he fished for trout in the cold mountain streams.

But there was one respect in which Princip’s early years were very far from average.

The boy utterly excelled at school.

In a time and place where illiteracy levels stood at a staggering 88 percent, Princip taught himself not just to read, but to read books that would make War and Peace look like Clifford the Big Red Dog.

In doing so, he discovered a whole other world.

In the cities, the early 20th Century was a time of great, frantic change. There was automation; electricity; the earliest twinklings of mass production. A world of speed, energy, transformation. As Princip read about this, boys from the nearby villages were already heading to Sarajevo; his older brother Jovo among them.

It was inevitable the younger boy would follow him.

In 1907, aged 13, Princip and his father set out to walk the 200-odd km to Sarajevo.

Petar hadn’t wanted the boy to go, insisting the family couldn’t afford it.

But then Jovo – by now a successful small-time timber merchant – had offered to pay Princip’s schooling fees and the deal had been sealed. A few weeks later, Princip was amid the bustle and energy of Sarajevo, ready to start a new life.

It was sheer coincidence he arrived just as the mother of all crises erupted.

While Princip had been learning to read, relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia had been worsening. In 1903, a group of hardline nationalists had murdered Serbia’s king, and brought Petar Karadjordjevic to power.

Karadjordjevic had severed Serbia’s remaining ties with Austria, and started cozying up to Vienna’s rival, Russia.

But while this had strained things between the two states, the big break came in 1908.

That October, the Habsburgs straight-up annexed Bosnia.

Although Austria had de facto ruled Bosnia for 30 years, making it de jure nearly sent Europe to war. Serbia was furious. In Belgrade, the move was seen as the first step towards an Austrian takeover.

In the end, the crisis resolved when Germany gave Austria its unconditional backing.

The only powers capable of taking on Berlin – France and Britain – didn’t care enough about Bosnia to start a war; while the one power that did care – Russia – was far too weak to tangle with Germany.

So the crisis passed, at least on the world stage.

But on the ground, in Serbia and Bosnia, it became a catalyst. In the wake of the annexation, the first shoots of Bosnian nationalism began to emerge. People who’d never considered the question before became champions of an independent Bosnia.

As this wave of revolutionary anger swept through the coffee houses and taverns, through the bazars and schools, Gavrilo Princip found himself getting swept up too. The boy began to devour anarchist literature – a radical move at a time when anarchists were assassinating kings, presidents, and empresses.

He fell in with two like minded Bosnian-Serbs: Nedeljko Cabrinovic and Trifko Grabez. Together, the three joined protests; daubed anti-Habsburg graffiti on walls.

Finally, in 1910, the new nationalist movement got its first martyr.

On June 15, Bosnian-Serb Bogdan Zerajic fired five shots at Bosnia’s military governor on a bridge near Princip’s home. All five shots missed, and Zerajic used the sixth bullet to commit suicide. When Princip rushed outside to see the commotion, he saw the stones still stained with Zerajic’s blood.

It was a gory sight. But it was something else to the teenage Princip, too.

It was a major inspiration.

Belgrade Blues

Come 1911, the general feeling of revolution had started to coalesce into specific groups.

In Serbia proper, Ujedinjenje ili smrt – known in English as the Black Hand – cropped up, a pet project of one of the 1903 regicides, and current head of Serbian Intelligence: a man known as “Apis”.

Over in Bosnia, the key group was Mlada Bosna (“Young Bosnia”).

Possibly created with help from the Black Hand, Mlada Bosna’s goal was to free Bosnia from the Habsburgs, and join it in union with Serbia. Naturally, this appealed hugely to Bosnian-Serbs like Princip. By now, Princip had almost given up on school. His entire mind, all his energies were devoted to mourning the plight of Serbia and building his hatred towards Austria.

In today’s terms, we’d say he was being radicalized.

Princip finally broke from regular life in 1912.

That year, he was kicked out of school for attending an anti-Habsburg rally; in some versions after threatening pro-imperial classmates with knuckledusters.

Angry, directionless, Princip wanted to leave Sarajevo behind. To go to Serbia and help fight the good fight.

He was about to get his chance.

In October of 1912, the First Balkan War erupted.

Pitting the Kingdoms of Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro against the decaying Ottoman state, it was the best chance yet to kick the Turks out of the Balkans for good. Like a radicalized teen going to Syria, Princip dropped everything, and walked the 280km to Serbia to volunteer.

Supposedly, the first thing he did on crossing the border was fall to his knees and kiss the Serbian soil.

If that tale is true, it must’ve made what came next seem all the worse.

Belgrade in the winter of 1912 was awash with officers trying to recruit more troops.

But when Princip eagerly tried to join up, his tiny frame and sickly complexion got him literally laughed out recruitment centers.

And so it was that Gavrilo Princip missed his great chance to be part of the story of Serbia.

What happened next is hazy, because not much documentation exists, and historians have wildly different theories. But it’s generally agreed that Princip stayed on in Belgrade; joined once again by his radicalized friends Cabrinovic and Grabez.

In some versions, Princip was forced to sleep rough in doorways. In others, he was the one supporting the others via small stipends from his parents. Yet they still had enough money to submerge themselves in the radical coffee house scene; a scene where Bosnian-Serbs met to plot revolution.

There, the three boys soon came to the attention of Belgrade’s ultra-nationalist groups.

How exactly this happened is up for debate.

Of the two the recent best English language books on the subject – Tim Butcher’s The Trigger, and Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers – Butcher’s book claims Princip self-radicalized, while Clark’s book says he was groomed by the Black Hand.

Either way, as 1913 rolled on, Princip’s thoughts turned more and more towards violent action.

In no time at all, those thoughts would stop being mere thoughts, and become a terrifying reality.

The Dominoes Fall

By May, the First Balkan War was going so well for Serbia that Austria started to panic.

In Bosnia, the military governor declared a state of emergency, closed Serb institutions, suspended the courts, and shut the Bosnian parliament.

Up in Austria proper, the Army Chief of Staff von Hotzendorf started stomping around demanding an invasion of Serbia.

Ironically, the man who stopped him was Princip’s future victim: Archduke Franz Ferdiand.

Ferdinand was the biggest dove at the Viennese court, the lone voice agitating against starting a major war in the Balkans.

Spoiler alert: his death was gonna wind up causing it.

Come summer, 1913, the Ottomans had been all but driven out the Balkans, and Serbian territory majorly expanded. For Princip and his mates, this was all the evidence they needed that the impossible would soon happen; that the peninsula would soon be free of imperial powers.

That winter, Princip stayed with his parents in chilly Obljaj.

But when he returned to Belgrade in March, it was to news that hit him like a haymaker to the groin.

All over the Serbian capital, headlines blared from newspapers: Franz Ferdinand was going to visit Sarajevo that summer. His chosen date?

June 28.

As you may recall from 3 sections back, June 28 was the date of the Battle of Kosovo – a date so emotionally charged for Serbs it’s almost like combining July 4 with 9/11. Now imagine you heard 9/11/7/4 was going to be marked by a genetic crossbreed of Osama Bin Laden and King George III stomping around New York, declaring jihad and trying to tax people without representation.

There. That’s how Bosnian-Serbs felt about Franz Ferdinand’s visit to Sarajevo.

All that spring rumors swirled. That Ferdinand’s visit was meant to cover-up a surprise Austrian attack on Serbia.

As the rumors intensified, Gavrilo Princip made an important decision.

He decided to kill the Archduke.

Or did he?

In his magisterial book The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark suggests the plot didn’t originate with Princip, but with Apis – the shadowy head of Serbian Intelligence. In this telling, Apis knew the dovish Ferdinand wanted to make peace with his Balkan subjects, maybe even elevating them to co-equals in his empire.

Since this would destroy Belgrade’s hopes of an independent Bosnia, Apis directed the Black Hand to recruit an assassin.

The Black Hand chose Princip.

That spring, Princip, Cabrinovic and Grabez practiced target shooting in Belgrade.

By now, the Serbian capital was frothing with outrage at the Archduke. Newspapers called him a “dog”, and his wife “a filthy Bohemian whore.”

It was amid this climate of hatred that six small bombs and four revolvers went missing from the Serbian state arsenal.

On May 27, they were passed to Gavrilo Princip. Four nights later, the Black Hand’s “underground railway” smuggled Princip and his friends across the Bosnian border. A network of Bosnian-Serbs helped all three conspirators reach Sarajevo, where they hooked up with a local cell from Mlada Bosna.

As June dawned in the capital, Princip spent his nights at the grave of Bogdan Zerajic, meditating on what needed to be done. Only a few short kilometers away, Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, were staying at a Bosnian retreat, unaware of Princip’s plans.

In perhaps the creepiest moment of this entire tale, they made a clandestine trip to Sarajevo on June 25, to wander around the Bazar. Unknown to them, Princip just happened to be there. The teenage boy trailed them like a shadow, studying their every move.

It was the first time Princip had ever seen the Austrian heir up close.

Sadly for Europe, it wouldn’t be the last.

Death in Sarajevo

The morning of the assassination, crowds thronged alongside Sarajevo’s Miljacka River, waiting for a glimpse of the royal couple. Princip and his co-conspirators spaced themselves out along the route. Each carried a weapon: a bomb or a loaded revolver. They also carried small packets of cyanide.

This was to be a one-way trip. A chance to become martyrs like Bogdan Zerajic.

The day before had been rainy and cool, with poor visibility. But as Princip took up his position that morning, it was under a bright sun. It’s possible Princip wondered where all the guards were. State visits were usually accompanied by a show of military might; but today there was no security.

Finally, in the distance, the boy spotted his target.

Despite being the assassin everyone remembers, Princip wasn’t actually the first in line. That honor fell to a young Bosniak who froze, unable to fire his revolver.

Second came Princip’s radical friend, Cabrinovic.

Unlike the Bosniak, Cabrinovic primed his bomb and threw it at Ferdinand’s car.

But the driver saw it and sped up. The bomb exploded beneath the car behind.

In a grimly humorous moment, Cabrinovic swallowed his cyanide and tried to hurl himself into the Miljacka; but the poison was so weak it only scorched his throat, and the river so low he simply went crashing into the bank.

At this stage, the assassination was closer to Mister Bean than a terrorist attack. By rights, Franz Ferdinand should’ve fled the city.

Instead, Ferdinand – who’d stopped his car to tend to the wounded – saw Cabrinovic being arrested, and uttered these fateful words:

“That fellow is clearly insane, let us proceed.”

Meanwhile, Gavrilo Princip had heard the bomb go off, heard the screams, and assumed the assassination had succeeded. He was running towards the commotion, a feeling of triumph already washing over him, when he saw the Archduke go sailing past in his car, completely unharmed.

We can only imagine what Princip thought in that moment, but we’re guessing it was the Serbian equivalent of “oh shiiiii…”

But it turned out God was smiling on the teenager that day.

As Princip loitered on the corner of Franz Josef Street – and no, the story about him stopping for a sandwich sadly isn’t true – Archduke Ferdinand was in Sarajevo city hall, demanding to be taken to see the wounded. Local officials tried to talk him out of it, but Ferdinand was adamant. So it was decided they would change the route, just in case other assassins were lurking.

But no-one thought to tell the driver.

And so it was that – instead of carrying straight along the river – the car carrying Ferdinand swung onto Franz Josef Street right next to Gavrilo Princip.

Incredibly, this wasn’t the final thing that had to go wrong to seal Ferdinand’s fate.

Princip was so astounded to see the car return that he wouldn’t have had a chance in Hell of getting a shot off if the driver had just kept on driving.

But someone shouted “Hey! You’re going the wrong way!”

So the driver stopped. Right there. Just meters from Princip.

As Princip later told it, time seemed to slow down.

He tried to use his bomb, but it got caught in his coat. So instead he pulled out his revolver, ran to the car, and pointed it at the couple. According to his testimony, he locked eyes with the Archduke’s security man, who blinked stupidly.

Then there was a crack! followed by another sharp crack!

And then the car was speeding away, as a crowd fell on Princip, kicking him, punching him, trying to kill him.

In the middle of the melee, Princip tried to shoot himself, only to feel the gun torn out his hand. He went for his cyanide, but it was kicked away. Gavrilo Princip was very nearly lynched that morning; his life only saved when a policeman managed to arrest him.

At that moment, Princip still didn’t know he’d been successful. Still didn’t know that one of his two bullets had passed through Franz Ferdinand’s neck, severing his artery.

That the other had killed Sophie, leaving nothing of the royal couple.

Shortly after 11:00am, the heir to the Austrian Empire was pronounced dead.

As bells began ringing across Sarajevo in mourning, it’s likely Princip felt some satisfaction.

He’d done the deed. The Archduke was dead.

From now on, nothing would ever be the same again.

Death of the Old World

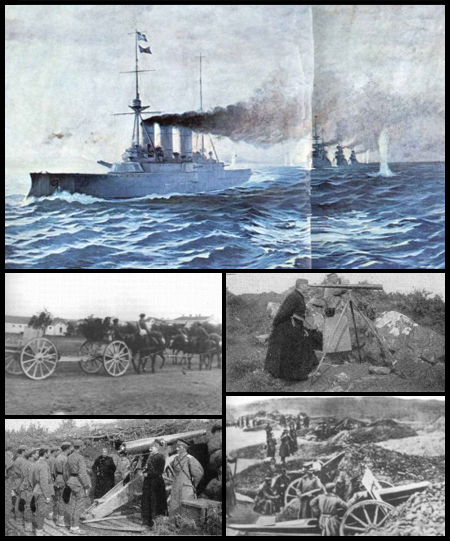

Whole books have been written about how this one assassination sparked one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. The super-basic version is that Austria-Hungary decided the Serbian state had ordered the killing, and invaded the Balkan kingdom.

One by one this tripped the switch on a complex series of alliances, each bringing some new ally into the fight, until the entire continent was pulled into what should’ve been a minor war.

And, well you know the rest. The barbed wire. The trenches. The gas. The millions upon millions of dead.

By the time Princip was put on trial, on October 17, the slaughter was already well underway.

The trial of Gavrilo Princip is today notable for two things.

One is that it gave him a chance to declare his motives.

Unlike the popular image of Princip as a Serbian nationalist, the young man said he was a South Slav-ist, dedicated to kicking the Austrians out the Balkans so all South Slavs could join into a single state.

The second is just how close Princip came to getting the death penalty.

Remember at the very start, when we said no-one knew if Princip had been born on 13 June or 13 July 1894?

Well, in Austria, the death penalty couldn’t be applied to anyone under 20 when they committed the crime.

If Princip had been born on June 13, he’d hang. If the real date was July 13, he’d only go to prison.

In the end, the court accepted the later date. Princip had been 19 when he shot Franz Ferdinand. Executing him would be against the law.

On October 28, 1914, Princip and his co-conspirators were found guilty.

While most of his compatriots would hang, Princip was given 20 years in Terezín fortress in modern-day Czech Republic.

But don’t go thinking he got off lightly.

The Austrians wanted Princip to suffer. He was kept in isolation, and ordered to go without food for one day every month.

By now, Princip was already showing signs of the tuberculosis eating away at his system. No-one doubted that this sickly young man would be dead before the end of his sentence.

But Princip was dead even before the end of the War.

Gavrilo Princip died on April 28, 1918, aged just 23.

Less than seven months later, in early November, 1918, Austria-Hungary completely collapsed; going the same way as both Imperial Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

By now, around 20 million had died. As the war ended, Bosnia joined with Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, and Montenegro into a single state.

Two years later, Princip’s remains were returned to Sarajevo, where he was reburied as a hero.

But Princip’s reputation didn’t stay settled for long.

During the postwar decades, when Princip’s dream of a united South Slav nation was an actual, real thing called Yugoslavia, the teenage assassin was celebrated as an icon. But then Yugoslavia collapsed in the early 1990s, and Princip came to be seen as a dangerous Serb nationalist; a forerunner of monsters like Ratko Mladic.

In Sarajevo, the memorial to him was destroyed during the Bosnian War. By the time the dust settled on that gruesome conflict, local views on Princip mostly depended on ethnicity.

Ironically for a pan-South Slav nationalist, today it’s only the Serbs who celebrate him. The Bosniaks and Croats mostly regard him as a terrorist.

Whatever your personal thoughts on Princip, though, there’s no doubting that he’s a significant figure.

Although we like to pretend otherwise, there was nothing inevitable about WWI.

Oh, sure, a European war was coming. But it was where the continent’s shifting alliances lay at that precise moment that made it so big, so deadly. Push the trigger back a few years, to when Russia was weaker; or forward a few years, to when the dovish Franz Ferdinand would’ve been on the Austrian throne, and the war might have looked very different.

Sometimes history changes slowly. Sometimes it turns on great moments.

For Gavrilo Princip, the penniless teenage boy from a peasant background, it was his destiny to stand at the heart of one of those great moments. To be the axis around which the future briefly turned, as he fired two shots that hot July day so many decades ago.

His moment in the spotlight of history may have only lasted a handful of seconds, but it was more significant than the lives of kings and presidents who spend decades there.

For that reason, if for no other, his short life deserves to be remembered.

Sources:

Link to The Sleepwalkers, superlative book on the outbreak of WWI: https://www.amazon.com/Sleepwalkers-How-Europe-Went-1914/dp/0061146668

Decent overview from the Telegraph (paywall): https://www.telegraph.co.uk/history/world-war-one/inside-first-world-war/part-one/10273752/gavrilo-princip.html

Excellent dual overview of both Princip and Franz Ferdinand – lots of sources: https://www.thespec.com/news/world/2014/01/11/an-assassin-and-his-prey-the-winter-before-war.html

LRB: Overview and a rebuttal: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v36/n20/mark-mazower/once-there-was-a-bridge-named-after-him

Christopher Clark on Tim Butcher’s Princip biography: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/apr/30/trigger-hunting-assassin-war-tim-butcher-review-masterpiece

New Statesman – Tim Butcher’s biography: https://www.newstatesman.com/international-politics/2014/07/gavrilo-princip-assassin-who-triggered-first-world-war

History Today: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-matters/sarajevos-elusive-assassin

Princip’s bio from the Bosnian side: https://www.inyourpocket.com/sarajevo/The-Boy-Behind-The-Trigger:-Who-Was-Gavrilo-Princip_73867f

Busting the sandwich myth: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gavrilo-princips-sandwich-79480741/

Geographics on Sarajevo (inc. facts on Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6oIUKPWU4g

Biographics on Franz Ferdinand: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ryw98zbzvuU

History of Bosnia: https://www.britannica.com/place/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-under-Austro-Hungarian-rule

Bosnian Crisis: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/austria-hungary-annexes-bosnia-herzegovina

History of ethnic tensions in the Balkans: https://www.ricksteves.com/watch-read-listen/read/understanding-yugoslavia

History of Serbia: https://www.britannica.com/place/Serbia/The-disintegration-of-Ottoman-rule

NPR, Princip’s shifting legacy: https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2014/06/27/326164157/the-shifting-legacy-of-the-man-who-shot-franz-ferdinand

How Princip is seen today: https://balkaninsight.com/2014/05/08/sarajevo-assassin-s-gunshot-echoes-across-his-birthplace/

1 Comment

very well written and easy to read, I like everything Morris M has to say