“Gould, with his 70 millions, was one of the colossal failures of our time. He was a purely selfish man. His greed consumed his charity. He was like death and hell – gathering in all, giving back nothing.”

These were words spoken at a sermon shortly after Jay Gould’s death and they are representative of what most of the American public thought about the rich industrialist. He was regarded as one of the worst examples of the robber barons who thrived during the economic boom of America’s Gilded Age. Gould became one of the richest men in the country and he didn’t care who he had to crush to achieve his goals.

Many of the methods Gould employed would simply be illegal today, but even back then, they were enough to make him hated by his fellow businessmen, but there was another group who hated him even more – the press. Gould operated during the rise of yellow journalism pioneered by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Their newspapers focused on scandals and sensationalism to sell copies, a technique which worked wonders.

Some historians who are trying to rehabilitate Jay Gould’s image argue that he was a favorite whipping boy of the press, particularly Pulitzer’s New York World, which he actually purchased from Gould in 1883. They believe that the industrialist’s negative reputation was mainly a creation of the media and that Gould was not especially more or less ruthless than all the other business magnates of his time.

We’ll let you decide that for yourself. We will present you his story and you can draw your own conclusions regarding the quintessential robber baron Jay Gould.

Early Years

Jayson “Jay” Gould was born on May 27, 1836, in Roxbury, New York, the son of John Burr Gould and Mary More. He was descended from Scottish immigrants and New England puritans. His great-grandfather on his mother’s side, John More, came to America in 1772 and founded the small town of Moresville, known today as Grand Gorge. His son, John Taylor More, became an influential politician in New York who served as State Senator and as a member of the New York State Assembly multiple times.

By the time Jay Gould was born, most of that power and wealth had diminished. His parents were just quiet farmers and it was expected that Jay would follow in his father’s footsteps. However, he had no interest in farming so, instead, he began working various odd jobs after receiving a basic education at the school in Hobart, New York. First, Gould worked at his father’s store and, in his free time, taught himself surveying. He was good enough that he turned this into his new profession for a few years. After he surveyed several of the southern counties of New York, Gould wrote and published a book when he was only 19 years old titled History of Delaware County, and Border Wars of New York.

Afterwards, Gould was employed in a blacksmith’s shop where he learned about a different trade that would become his first true business – leather tanning. During the 1850s, he used the money he had saved up to open a tannery in Pennsylvania, in an area that would later become the town of Gouldsboro in his honor. He did this in partnership with a man named Zadock Pratt. Forty-five years older than Gould, Pratt once operated the largest tannery in the world in the Catskill Mountains. However, as he advanced in age, he preferred instead to finance multiple, smaller tanneries and let his younger partners do the hard work. That is also what he did with Gould, although their partnership only lasted for a few years before Pratt retired for good and his up-and-coming coworker bought out his share.

Young Businessman

Pretty early on, Jay Gould concluded that any serious money would be made in New York City. Therefore, as soon as he made some significant cash from his tannery, he moved to the city and began speculating on the stock market.

At this time, Gould also partnered with a leather merchant named Charles Leupp, but their joint venture ended on considerably worse terms than with Pratt. Gould was a risk-taker. He used the money that he received from investors, primarily Leupp, to try and corner the hide market. However, then came the Panic of 1857, a financial crash which was greatly exacerbated in the United States by the sinking of the SS Central America, a ship carrying a giant shipment of gold from California. Banks took heavy losses and investments went bottoms up. Leupp lost everything and ended up committing suicide.

In the decades that followed, the story that went around was that Gould intentionally drove his partner into poverty and death by making dangerous transactions so that he would then be able to buy out all his properties for cheap. This is a good example of the kind of tales that were propagated about Gould in his own time, detailing the viciousness of his business dealings, but there was little evidence to back them up. In this particular case, what Gould did was certainly risky, but he could hardly be blamed for the Panic of 1857. Furthermore, it had been documented that Charles Leupp suffered from mental problems such as depression and severe paranoia which, undoubtedly, contributed to his suicide.

That being said, Gould was certainly no saint, by any stretch of the imagination. After Leupp’s death, there was a dispute over ownership of the tannery in Gouldsboro between Jay Gould and another one of his investors, Leupp’s brother-in-law, David Williamson Lee. This dispute lasted for ten years and, eventually, the courts ruled in Lee’s favor. By that point, Gould was already a very rich man and the tannery wasn’t worth much, anyway, so he sold his interest to the Lee family for a nominal fee. It just goes to show the kind of man that Gould was – he was willing to fight tooth & nail for years for something he didn’t even care about just so he would not be the one on the losing side.

The Erie War

Once he was done with the tanning business, Gould became a fully-fledged stockbroker on Wall Street. He had a knack for this, but he also used every advantage at his disposal to manipulate the market to his advantage. This included tactics which, although unethical, were legal, such as short selling, but he was also alleged to have bribed politicians, judges, and anyone else necessary in order to pass favorable legislation and shut down laws that worked against him. However, he truly emerged as one of the country’s leading industrialists when he began getting involved in railroads.

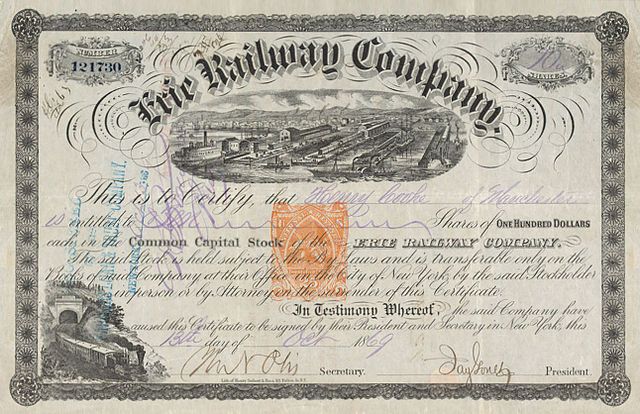

He first dipped his toes into these waters in 1857, right after the panic. As the stocks plunged, the Rutland & Washington Railroad that connected Rutland, Vermont, to Eagle Bridge, New York, was on the brink of bankruptcy. The opportunity presented itself to Gould to purchase a controlling interest in the railway for ten cents on the dollar. Afterwards, he had it repaired and, as the railroad managed to weather the financial storm of 1857, it became commercially successful again and, in just a couple of years, Gould sold it for a large profit. This was a nice start, but it mainly served to show the businessman that a lot of money can be had in railroads. He then set his sights a lot higher on the Erie Railroad, triggering a conflict between four of America’s richest men known as the Erie War.

The Erie Railroad was a very appealing target for anyone looking to invest. It was not only one of the longest railways in the country, but it also had a prime location as it crossed New York State, from New York City to Buffalo. Despite this, it experienced financial troubles during the 1850s due to poor management and large building costs. In came Daniel Drew, one of the protagonists of the Erie War. He was a financier who originally made his money from cattle, but had his fingers in many lucrative pies. He loaned the struggling railroad $2 million which earned him a place on the board of directors. Of course, this would have been only the beginning for Drew, as he fully intended to gain a controlling interest of the railroad, but he soon discovered that he had very stiff competition from Cornelius Vanderbilt, the richest man in America and someone we have already covered here on Biographics if you want to go check that out.

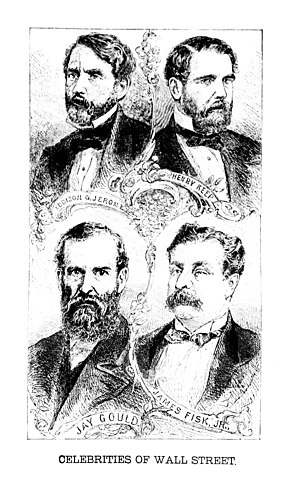

Anyway, Drew realized that he had little hope of going against Vanderbilt alone, so he found two partners. They were Jay Gould and another stockbroker named “Diamond Jim” James Fisk. Together, the three of them conspired to trick Vanderbilt. Since they knew that his intention was to corner the market and buy all the available stock in the Erie Railroad, they “watered it down,” meaning that they kept issuing additional stock and artificially inflating its value. This wasn’t legal, not even back then, and, in 1868, the three financiers had to flee New York City after a judge ended their activity and cited the entire board of directors of the Erie Railroad to appear in court. In a truly bizarre moment that the press ate up, the trio barricaded themselves in a New Jersey hotel and hired bodyguards to protect the entrances around the clock.

All they needed was to stall for time as they had an ace up their sleeve. It was their connection to Tammany Hall, the highly-corrupt, highly-influential Democratic Party political machine ruled by William “Boss” Tweed. He arranged for favorable legislation which legalized their issue of stock in exchange for a director’s position on the Erie Railroad and, certainly, quite a lot of generous “donations.” Journalist Gustavus Myers who covered the scandal wrote how the New York politicians were eagerly accepting bribes from both groups and siding with the one who paid the most:

“Members of the Legislature impassively took money from both parties. Gould personally appeared at Albany with a satchel containing $500,000 in greenbacks which were rapidly distributed. One Senator, as was disclosed by an investigating committee, accepted $75,000 from Vanderbilt and then $100,000 from Gould, kept both sums, — and voted with the dominant Gould forces.”

Exactly how the Erie War resolved itself is unclear. Eventually, Vanderbilt and Drew called a meeting and reached an understanding with unknown terms. Vanderbilt backed off but got the Erie Railroad to buy back the “watered down” stocks he had purchased. And just to show that there truly is no honor among thieves, Fisk and Gould turned on Drew once Vanderbilt was out of the picture. In 1870, they again manipulated the stocks in such a way that their former partner lost money. He was later greatly affected by another financial crisis in 1873 and, by 1876, he had been forced into retirement after having to declare bankruptcy.

Daniel Drew died in 1879 completely penniless, the second of Gould’s partners to meet such a fate. Meanwhile, James Fisk had been murdered in 1872 while “Boss” Tweed was imprisoned on multiple corruption charges. As for Gould himself, he was also forced to part with the Erie Railroad against his wishes, in a way that nobody saw coming.

Gould Meets Gordon

In the end, it wasn’t another wealthy industrialist who got the better of Jay Gould. It wasn’t the authorities, either, it was a con man who suckered Gould out of a million dollars and almost caused Minnesota to invade Canada.

His real name is lost to history, but he was known as Lord Gordon-Gordon. His main scam involved portraying himself as a Scottish nobleman and obtaining goods and services on credit. Of course, eventually, everybody called in the debt and the fraud was discovered so this scheme required a constant change of scenery.

Around 1870, Lord Gordon-Gordon had been exposed as a fake in London so he sought out greener pastures in America. He arrived in Minnesota where he posed as a lord looking to invest lots of money. He even deposited around $40,000, all the money left over from his previous swindles, in a local bank. This was enough to convince everyone that he was legit and he soon made the acquaintance of officials from the Northern Pacific Railroad who were looking for investors. They wined & dined Lord Gordon, sparing no expense in trying to persuade him to purchase railroad land. Eventually, he agreed to their terms, but said that he needed to travel to New York first, and make arrangements for the money transfer. He left Minnesota never intending to return again, with the people he conned smiling and waving him good-bye.

Gordon-Gordon made an immediate splash in New York. He booked a lavish penthouse for himself and had letters of introduction from his former “partners” in Minnesota so he quickly injected himself in the upper crust of society. Through discussions with Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New-York Tribune, Gordon discovered that there was a power struggle going on for control of the Erie Railroad. Somehow, the Scottish “lord” managed to convince Greeley that he owned tens of thousands of stocks in that railroad alongside his European associates. He let the word spread and, soon enough, he received a visit from Jay Gould.

The American industrialist was already working on his own scheme to gain control of the railroad and the last thing he needed was to have a European consortium come in and pull the rug from under him. He wanted to strike a deal with Gordon – pool their resources together, Gould takes control of the company, and the Scottish nobleman names the directors of his choosing to look after his interests.

Lord Gordon pretended to be intrigued, but also reluctant. Why would he trust Jay Gould? He asked for a guarantee – a million dollars in stocks and cash, not to spend, but to keep as a sign of good faith until their business was concluded. Gould immediately accepted, and it took him a while to realize he had been conned when Gordon began cashing in the stocks that, theoretically, he said he wouldn’t touch. He sued Gordon and took him to trial in March 1873. He also contacted the Scottish aristocrat’s alleged associates in Europe who all said that they had never heard of Lord Gordon-Gordon. It would have been an easy conviction, but Gordon fled to Canada before being arrested.

This was bad for Gould. Besides the money he had lost from the stocks Gordon had cashed in, he lost even more once word got out of the swindle, causing the value of the Erie Railroad stocks to go down. But he wasn’t the only one who wanted to get his hands on Lord Gordon because his targets from Minnesota also heard of the conman escaping across the border. It is uncertain exactly what role Gould played in what happened next, but a group of prominent Minnesotans went to Canada and kidnapped Lord Gordon-Gordon, hoping to bring him back to the States. However,they were caught at the border, arrested and held without bail.

Minnesota Governor Horace Austin was ready to raise a militia and invade Canada in order to get his men released. It took intervention from U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and Canadian Prime Minister John Macdonald to avoid an international incident. Once the extent of Gordon’s crimes were established, the Canadian government agreed to extradite him, but the conman committed suicide before this could happen.

As for Jay Gould, his connection to Lord Gordon-Gordon had been a disaster. Ignoring the money he lost personally, the damage he caused to the stock of the Erie Railroad gave his opponents on the board of directors all the ammo they needed to force him out of the company. After all the years, the bribes, and the betrayals, none of the participants in the Erie War got to enjoy the prize they fought so hard over.

Black Friday

Although Gould lost the Erie Railroad, he did not abandon the industry altogether. Instead, he looked for new opportunities out west and still managed to amass quite a large railroad empire for himself. He started by buying the Union Pacific which had been hurt dramatically by the Panic of 1873. He then purchased a few other railways whose stock had plummeted and made repairs and improvements on all of them. Once the economy began to recover, he sold his stock for large profits.

Besides transportation, Gould also got involved in communications, particularly telegraph companies. In 1875, he took over the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company, one of the main competitors to Western Union. He then initiated a rate war with all the other companies, eventually selling A&P to Western Union for another nice profit.

This is all well & good, but it doesn’t really have the scandal and controversy that we have come to expect from Gould’s business ventures. For that, we have to travel into the past just a bit to 1869, back when he was still partnered with James Fisk for all their shady wheelings and dealings. The two enacted a scheme to try and corner the gold market that involved the President of the United States himself and shook the foundations of the American economy. It became known as Black Friday, the original Black Friday, a term which has since been used to refer to numerous disastrous events that occurred on this day of the week.

Gould and Fisk had made the acquaintance of a man named Abel Corbin. He was a small-time financier and speculator, but he also happened to be married to Virginia Grant, sister of President Ulysses S. Grant. Through him, the duo met the president and entered his confidence.

![From Wikimedia Commons: Title: Cut-throat business in Wall Street. How the inexperienced lose their heads Abstract: Print shows William H. Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Russell Sage and James R. Keene checking ticker tape connected to a large straight-edge razor labeled "Wade in & Butcher'em" and "This Indicator Rises & Falls with Stocks" with a bear and a bull and several money bags labeled "$" balanced on the back of the blade; below, draped over the handle are many investors reaching for bundles of "Pacific Mail, Western Union, [and] Erie" stocks, the blade is poised to drop. In the background another group of investors labeled "The Lambs Brigade" are headed into the "N.Y. Stock Exchange". Physical description: 1 print : chromolithograph. Notes: Illus. from Puck, v. 9 [i.e., 10], no. 235, (1881 September 7), centerfold.; J. Keppler.; Copyright 1881 by Keppler & Schwarzmann.; Title from item. See also the bigger German version:](https://biographics.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/640px-Cut-throat_business_in_Wall_Street._How_the_inexperienced_lose_their_heads_LCCN2012647282.jpg)

After being introduced by Corbin, Gould and Fisk casually brought up the subject of gold with President Grant at various social gatherings. They both argued against the government sale of gold and, of course, they were backed up by Abel Corbin. They also had a man on the inside named General Daniel Butterfield who was assistant treasurer and informed them when the government was getting ready to sell.

All the pieces were in place to make a killing on the gold market. Gould and Fisk amassed a large supply of gold and, when the Treasury stopped selling, they just sat back and watched the value of their investment go through the roof. Of course, they intended to unload it right before the Treasury started selling again to maximize their profits, but their plan backfired. Eventually, Grant realized he had been swindled and ordered the immediate sale of $4,000,000 in gold. This caused the value of the precious metal to plummet, plunging the entire stock market into chaos. This happened on September 24, 1869, a date which became remembered as Black Friday.

Many speculators and investors were ruined that day, but Gould and Fisk made out nicely. They heard of Grant’s plan from Butterfield and had time to sell off most of their gold reserves. They also avoided any legal repercussions, partly because they were smart in how they carried out their scheme, but mainly because they were tried in New York where they were protected by friendly judges who were associates of Boss Tweed.

Final Years

We haven’t really talked about Jay Gould’s private life so far because there was nothing spectacular to mention. He married Helen Day Miller in 1863 when they were both in their mid-20s. They had six children together who did what you would expect for that time period: the men became businessmen and investors like their father and the women became socialites and philanthropists.

Gould contracted consumption in 1892, what we call tuberculosis today, and he died on December 2, aged 56. His wealth was placed at around $72 million at the time of his death, although more recent estimates claim it was closer to $100 million, but that Gould intentionally downplayed his wealth for tax purposes.

As you might expect, there weren’t many kind words said about Jay Gould after he died, with one pastor decrying him as “the human incarnation of avarice — a thief in the night stalking his fellow man.” The newspapers were even harsher, although many did concede that Gould had tremendous business acumen. Nowadays, some historians look upon his legacy a bit more favorably and argue that, while Jay Gould was no philanthropist, he did do some good, particularly improving the infrastructure of the country’s railroad network.