Military theorist Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart once lamented that history too often glorifies those who are defeated in war, while it may forget the victors. While Napoleon and Robert E. Lee are enshrined in drama, Wellington and Grant are almost forgotten, he wrote.

This may be true for today’s protagonist. A brilliant military strategist who, at a very young age, led Rome in a series of spectacular victories against the greatest threat ever faced by the Republic: Hannibal of Carthage.

And while Hannibal is a household name, the life and merits of his chief Roman rival may be lesser known. In today’s Biographics, we will learn about Publius Cornelius Scipio, known for his accomplishments as ‘Africanus’. He is a general which Sir Basil himself labeled as ‘greater than Napoleon’.

First Steps

Publius Cornelius Scipio was born in the year 235 BC to a powerful patrician family. His father, Publius Sr, was a well-respected political leader and military commander.

The life of Publius Jr. has been chronicled by several Latin and Greek biographers, Polybius and Livy among others. But these Whistlers of the past have written very little about the childhood and early teens of our protagonist.

We know that Publius may have been born via Caesarian section, considered a sign of future greatness. Livy even reports that Publius was conceived by his mother and a giant serpent. This same story was told about Alexander the Great, so it may have been a common myth told about great Generals.

From the boy’s early teens, we only have one disputed anecdote. In this story, we learn how Publius Sr had to drag a semi-undressed Junior from the bed chamber of an older lady friend, in just enough time to prevent a scandal.

Was this a common occurrence? Was Publius Jr, the Son of the Serpent, something of a precocious ladies’ man, chased around Rome by a prudish father?

The truth is: we don’t really know. But what a great theatrical narrative it would make! Publius Jr as a spoiled aristocratic brat and trouble-maker, who slowly comes to accept his responsibilities toward his family and his motherland, in the time of need.

And ‘time of need’ describes the catastrophe that threatened to destroy Rome. This was the invasion of Italy by the Carthaginian General Hannibal.

At some point, you may want to watch our Biographics episode about Publius’ foil, Hannibal, but here are the basics.

![Bronze bust formerly identified as Scipio Africanus in the the Naples National Archaeological Museum (Inv. No. 5634), dated mid 1st century BC. Excavated from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum (modern Ercolano, Italy) by Karl Jakob Weber, 1750-65.[1]](https://biographics.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/436px-Escipion_africano.jpeg)

After more than two decades of fighting, Carthage had to sue for peace, yielding the island of Sicily to Rome; one generation later, in the year 219, Carthaginian forces in Spain were led by Hannibal Barca, the son of Hamilcar, or the Son of the Thunderbolt. Hannibal and his forces had resumed hostilities by attacking Saguntum, a Spanish city allied with Rome. That kicked off the Second Punic War.

Whereas most of the first conflict centered around island combat and naval battles, Hannibal surprised Rome by taking the fight to Italy. He made a wild gambit by leading his army of 26,000 men, plus Elephants, over the snowy peaks of the Alps and into the northern portion of the Italian peninsula. Hannibal was happy to take crazy, calculated risks — he was hellbent on avenging Carthage’s previous defeat, which had sullied the name of both his father and his country. In short, he wanted revenge, and he had the right combination of brains and brawn to get everything that he wanted.

Disaster at Cannae

In 218 BC, Publius Sr was one of the two Consuls leading the Roman Republic, and Publius Jr was barely 17. The older Scipio was tasked by the Roman Senate to lead an army in Northern Italy, to oppose the incoming troops of Hannibal. Publius Jr followed his father and was put in command of a squadron of mounted bodyguards.

The two armies clashed in the battle of the Ticinus river. According to Polybius, Publius Sr was surrounded by Carthaginian cavalry during the battle and seriously wounded. Seeing this, his son spurred on his horse and charged alone into battle. The other cavalrymen, moved by his courage, followed him into the desperate attack.

Caught by surprise, the Carthaginians broke formation and fled. Publius Sr, wounded but still conscious, hailed his son as his savior.

This event cemented Scipio’s reputation as a courageous leader.

Clearly, Rome was in dire need of men like Young Scipio, as Hannibal soundly defeated the Romans on the Ticinus and continued his march along the Italian ‘boot’.

The brilliant General thrashed the Romans at the battle of the Trebia River, and then again at the Lake Trasimene.

We don’t have any evidence that the young Scipio participated in these battles. What can be speculated, though, is that young Scipio may have listened carefully to the accounts of these defeats, trying to learn what made Hannibal so lethal.

Was it the elephants? Sure, Hannibal had a contingent of war elephants, which terrified and crushed the legions.

Or was it the cavalry? The Carthaginians were allies of the Numidians, a North African group who could boast some of the finest cavalrymen of the time.

Was it Hannibal’s knack to win new allies? General Barca was able to recruit numerous allies, first among the Iberian tribes, and then among the Celtic tribes in Northern Italy.

Sure, it was all of the above. But what made of Hannibal a victor was his brilliant tactical mind, which did not refrain from the use of stratagems, traps, and ambushes to gain the upper hand in battle.

On the other hand, the Roman Republic excelled in discipline and logistics, but lacked tactical creativity. They didn’t even have a word for ‘stratagems.’ Romans considered them to be dishonourable!

Their two opposing concepts of warfare would be put to the test once more at the next big battle.

On the 2nd of August, 216 BC, the Romans and Carthaginians faced each other near the town of Cannae, in modern day Apulia, the ‘heel’ of the Italian boot.

Hannibal fielded 40,000 foot and 10,000 mounted soldiers. The Romans were led by the two newly elected Consuls Lucius Aemilius Paulus and Gaius Terentius Varro. Their army was stronger, consisting of 80,000 legionnaires. But both the commanders and the troops lacked the experience of their opponents.

At Cannae, Hannibal painted a masterpiece in Roman blood: a total and perfect encirclement of the enemy army. The Carthaginian general placed his troops in a slightly convex formation, rather than the traditional line.

His advanced troops at the centre first goaded the Roman centre to advance, then slowly withdrew. As they did so, the wings of the formation surrounded the Roman Legions from both sides. Finally, Hannibal’s cavalry attacked from the rear, preventing any chance to run away.

The trap closed shut, and the youth of Rome was annihilated by the Carthaginian meat grinder. Many of the army leaders died, including consul Aemilius Paulus. 48,000 legionnaires fell to their enemies – and that’s the most conservative number! The mortality rate has been estimated to be 500 deaths per minute.

In little more than 90 minutes, Rome lost more men in battle than Canada did in the whole of World War 2. Or almost as many men as the US in 10 years of War in Vietnam.

Publius Cornelius Scipio Jr was there, as a 19-year old Tribunus, or junior officer. We don’t have an account of what he did during the battle. We only know what he did afterward.

While the surviving legionnaires and officers were in shock, confused as to what to do, Publius displayed great leadership.

The young officer rounded up a group of survivors and led them to safety, past Hannibal’s men still looking for survivors. Marching in silence, at night, always leading the way to look for the safest route, Publius led his band to the safety of Canusium.

While on the run, Publius interviewed his men trying to understand what had caused such a disaster. How could an army be crushed so decisively? By studying the battle, Scipio started to develop an admiration for Hannibal.

Sure, General Barca was his enemy. But Publius would also consider him as his model, his master. And as we know, the destiny of every pupil is, one day, to surpass their master.

Cursus Honorum

After the victory of Cannae, Hannibal’s army failed to take initiative to storm Rome, preferring to rest in Capua, 30 km north of Naples. Legend has it that the Senate sent a special force of 300 dedicated Roman to stall their movements. Not 300 Spartan hoplites, but 300 prostitutes, whose sole job was to keep Hannibal’s soldiers busy.

Whatever the truth, the Carthaginian force did waste some time gallivanting in Capua. And later, they occupied Southern Italy, foraging on supplies and gradually gaining new regional allies.

Hannibal may have had a long-term strategy to weaken Rome until he forced it to surrender. But he had underestimated the strength of the bond between the Roman Senate and the Roman People.

This was a bond of trust which not even 500 deaths a minute could dissolve. Some allies may have switched sides, sure. But others perpetuated their allegiance to Rome, and Rome resisted.

If we now zoom into the Senate, we may find Scipio Jr again. It’s 213 BC, and Scipio is 22 years old.

Since Cannae, he had married Aemilia, daughter of Aemilius Paulus, the Consul who had died in that battle. The couple later had three children: Publius the Third, Lucius and Cornelia.

Scipio’s reputation for courage and leadership had accelerated his cursus honorum, the ladder of public offices leading to the Consulship.

Publius Sr would have been proud of him, had he been there.

While Hannibal had been plundering Southern Italy, the Senate had adopted a wise strategy: attack and harass the Carthaginian allies in Spain, to weaken them and cut them off from supplies. The Senate had dispatched Publius Sr and his brother Gnaeus (pronunciation: nI-us) to take care of the Iberian tribes.

In 211 BC, a massive Iberian-Carthaginian force attacked the Romans on the Baetis river, in modern-day Andalusia. The Romans were repelled as far back as Northeastern Spain. This defeat was compounded by a personal tragedy for Publius Jr: both his father and uncle had been killed in battle.

Like his Carthaginian foil, the struggle had now become personal.

The Senate needed to appoint a new commander abroad, a Pro-Consul, to continue the campaign in Spain. Publius Cornelius Scipio, barely 25, was elected almost unanimously to lead the expedition.

Of course, he accepted. To avenge Rome, his family, his father.

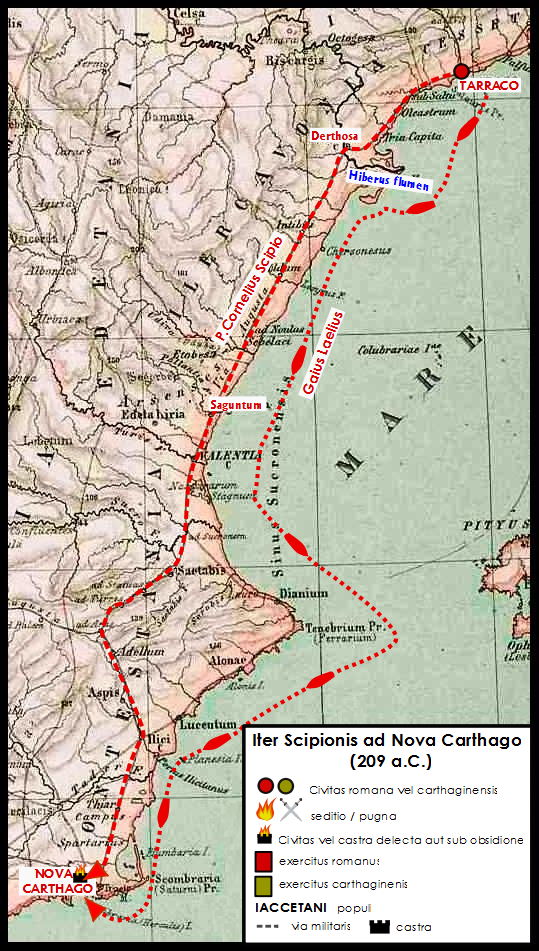

Scipio appointed Caius Laelius as his second in command, a trusted right-hand man from his earlier military days. The two sailed off to Tarraco – modern-day Tarragona – to take charge of the surviving legions.

The first act of the young General was to motivate those veterans to do the unthinkable. Rather than entrench themselves on the river Ebro – as they expected – they would attack their enemies in Central and Southern Spain.

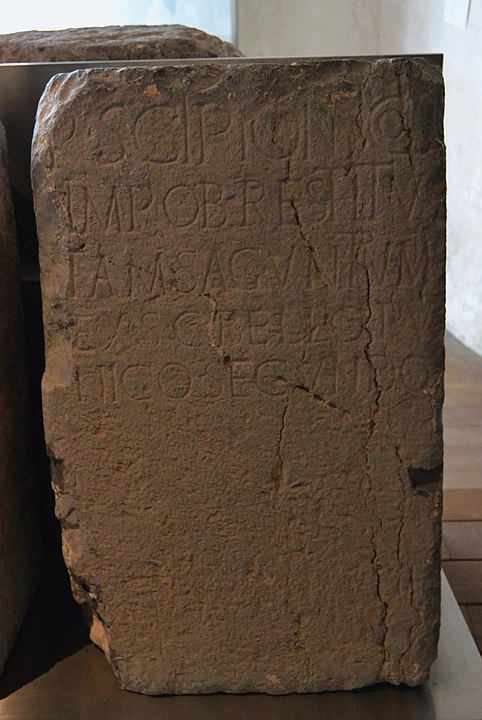

As his armies crossed the river, Scipio revealed his true objective. A city on the south-eastern coast, the very capital of the enemy in Spain: New Carthage.

The Rains of Ilipa

Modern military theorists Klima, Mazzella, and McLaughlin have analysed Scipio’s strategy from the perspective of the ‘Centre of Gravity’ battle theory, which calls for the identification and destruction of the true centre of an enemy army’s strength or balance.

Hannibal’s ‘centre of gravity’ was the support he received from Spain. And Spain’s ‘centre of gravity’ was New Carthage, known to be impregnable. Surrounded on three sides by the sea and a lagoon, it could be besieged only via a narrow isthmus.

But the crafty Scipio questioned some local fishermen, who told him about the tides, which at specific times were so low that one could walk across the lagoon.

Exploiting this natural occurrence, Scipio announced to his soldiers that he would part the waters with the help of Neptune, god of the sea. And at the expected time, the sea did withdraw from the lagoon. A contingent rushed to New Carthage and stormed the poorly defended walls.

After the victory, he allowed his troops to pillage and slaughter for a brief period, but then he imposed a strict discipline. Some of his prisoners belonged to the same tribes that had killed his father, but he released them all. He went one step further, offering artisans, sailors, and soldiers to join the ranks of the Romans.

After this conquest, Scipio had to square off with the three Carthaginian Generals in Iberia: Hannibal’s younger brothers, Hasdrubal and Magus Barca; and Hasdrubal Gisco, Hannibal’s brother in law.

The next engagement with the enemy was the battle of Baecula, some 350km west of New Carthage, in 208 BC. At Baecula, Scipio used his signature pincer tactic for the first time — he divided his main forces into two strong wings, which fell upon the Carthaginians’ flanks.

After the victory, Scipio showed again his penchant for long-sighted clemency. When he learned that a Numidian horseman called Massiva had been made prisoner, he ordered his release. The young soldier was a nephew of Massinissa, Prince of the Eastern Numidians, who would later show his gratitude.

The next big fight took place in 206 BC at Ilipa, near modern-day Seville. This was Scipio’s chance to wipe the floor with Magus Barca and Hasdrubal Gisco.

During this battle, Scipio took another step further away from Roman tactical tradition. A typical order of battle would be to field the heavy Roman infantry at the centre of a line, flanked by lighter auxiliary forces provided by local allies. The Carthaginians had a similar approach.

But at Ilipa, Scipio did exactly the opposite: his Iberian allies formed the centre, bearing the shock of the advance of heavily armed Carthaginian foot. As the Iberians slowly withdrew, the well-drilled Roman legions advanced in a pincer movement, crushing their opponents.

Magus’ and Hasdrubal’s armies risked annihilation, if it wasn’t for a violent and timely downpour. The sudden bad weather prevented the Romans from chasing their enemies, who managed to run for their lives.

That must have been disappointing for Scipio. Nonetheless, it appeared as though the rains of Ilipa had washed away the remnants of Carthaginian power in Spain.

Hasdrubal Gisco fled back to Carthage, while Magus Barca sought refuge in the Balearic Islands.

Their local allies had switched sides to Rome. And Scipio had made some powerful new friends: Prince Massinissa, and his legendary Numidian horsemen.

At the young age of 29, General Scipio had subjugated a new province, Hispania, for the glory of Rome.

But the fight was far from over.

In the same year, Scipio made a quick trip to Northern Africa to test the loyalty of Carthage’s allies, in particular the Western Numidians. He learned that their King, Syphax, was tied to the Carthaginians by marriage. His wife, the beautiful Sophon-baal, was the daughter of Hasdrubal Gisco.

Scipio’s friend Massinissa was the Prince of the Eastern Numidians. While both Massinissa and Syphax had been fighting on the Carthaginian side, they were at odds with each other. Politically, they both vied for total leadership of the unified Numidians. On a more personal level, Massinissa had long been in love with Sophon-baal, the newlywed of his rival!

During this trip, Scipio failed to turn the Western Numidians against Carthage, but he cemented the alliance with Massinissa, boosting both numbers and quality for his cavalry.

Scipio’s next trip was back home, back to Rome. He received a hero’s welcome and in 205 BC, he won the consulship, aged only 30.

Scipio wanted to continue leading the war against Hannibal, who was still holding onto Southern Italy. He was presented with two options: either confront Hannibal head-on in Italy, with the risk of a second disaster like Cannae, or continue with the delaying tactics imposed by Quintus Fabius Maximus, nicknamed the ‘delayer’. Maximus was the senior-most senator, who for years had supported a strategy of harassing Hannibal’s army to wear them down without giving in to a full-on battle.

Scipio chose none of the above. His strategy was to set up a base of operations in Sicily and use it as a launching pad for the invasion of Africa. A direct fight against Hannibal was still too dangerous, but he could destroy him by targeting another ‘centre of gravity’.

Scipio had already taken out the centre that had been providing Hannibal with recruits and supplies, in Spain. Now, he would target the centre of his authority: Carthage.

The Flames of Utica

The Roman Senate, influenced by Maximus, opposed this Command & Conquer strategy. It was too expensive and too risky. Historian Giovanni Brizzi also suggests that the family of the ‘Delayer’ may have had trade ties with the Carthaginian senators. It was not in their interest to threaten the wealth of their trade partners!

Eventually, Scipio and the Senate reached a compromise: he had permission to carry his plan, but he could not raise fresh legions for his African landing.

All Scipio received were the survivors of Cannae.

These soldiers were the Republic’s Rejects. Defeated and demoralised, humiliated and mistrusted by their own compatriots, accused of cowardice and desertion. These two meager legions had been refreshed with elements from disciplinary units — soldiers guilty of insubordination, theft, and other crimes.

But the young General would not allow himself to fail. He drilled into shape his ‘Dirty Dozen’ – or ‘Dirty 10,000’ – and then launched an appeal to the Italic allies. The allies responded to his call, sending money, food, weapons, raw material to build new ships, and even hundreds of fully-kitted soldiers.

Before heading off to Northern Africa, Scipio put his troops to the test in the invasion of Locri. This Southern Italian town had allied itself to Hannibal, but Scipio’s spies informed him that the tide was turning. The general took the occasion to send a landing party, which promptly stormed the town in a surprise night attack, chasing away the Carthaginian garrison.

This victory risked ruining all of Scipio’s grand plans. The three officers left in charge at Locri proved to be a gang of crooks; they terrorised the local population and even desecrated the temple of the main deity, the goddess Proserpina.

Maximus took the occasion to cry scandal. He asked for Scipio’s return to Rome and for a commission of enquiry to investigate the events in Locri. Luckily, the General still had some friends in the Senate, and they snuck a cousin of his into the commission to act in his stead… the trick worked, as the final report exonerated Scipio from any wrongdoing.

With the internal opposition taken care of, Scipio was now free to launch his invasion. In the Summer of 204 BC, he set sail from Sicily, leading an army of 23,500 foot and 2,500 cavalrymen. In other words, twenty-six thousand men — the same number that Hannibal had led into Italy years before.

Mere coincidence? Or perhaps Scipio was once again proving that he could study, emulate, and eventually best, his enemy.

Scipio and his army reached their first objective in Northern Africa, the city of Utica, on the coast of what is today Tunisia. The Romans were soon besieged by two armies: the Numidians, led by Syphax, and Carthaginian mercenaries under Hasdrubal Gisco.

Exploiting his previous acquaintance with the Numidian King, Scipio sent some ambassadors to discuss a peace settlement. This may have been against character, but Scipio could recognise when he was in a difficult spot.

The talks continued until the beginning of 203 BC, when Syphax and Scipio reached a compromise. Rome would retain control of Sicily and Sardinia, while Carthage would rule over the remaining islands of the Western Mediterranean.

Kyng Syphax relished his diplomatic skills. One night in March, he prepared to relax in his lodgings, surrounded by his formidable army. They had spent months inside a makeshift camp of wooden barracks, but the war was finally coming to an end.

A cry disturbed his peace, as a call spread wild among the sentries: ‘fire’!

In a matter of minutes, nearly the entire Numidian camp was ablaze with furious flames, consuming the tents and cabins, made of twigs and dry branches.

The soldiers tried to escape the inferno, only to be quickly cut down by devils hiding in the dark: Massinissa’s horsemen and Scipio’s band of rejects.

What had happened?

While conducting talks with Syphax, Scipio had sent some of his officers to the enemy camp, disguised as messengers or servants. The officers spied on the Numidians, taking note of the sentries, their shifts, and especially on the flammable nature of the camp.

After Syphax had lowered his guard, Scipio had sent his two most trusted deputies, Massinissa and Caius Laelius, to set the camp on fire.

While the Numidian army was being slaughtered, a detachment left from the nearby fort of Hasdrubal. Just as Scipio had planned, the Carthaginians were coming to help their allies. And just as Scipio had planned, Gisco’s forces were ambushed and massacred on the way there.

Out of the flames of Utica, Scipio’s rejects emerged triumphant. This was their first big victory in enemy territory. But something else emerged from the ashes, a new style of warfare previously inconceivable to the Romans — a tactical doctrine founded on stratagems, ambushes, and traps. It was yet another lesson learned from Hannibal, Son of the Thunderbolt. One that Scipio, Son of the Serpent, could not wait to turn against his master.

The Fields of Bagradas

Hasdrubal and Syphax managed to escape Utica. With support from his own senate, General Gisco raised another mercenary army.

These new units blocked the way to Carthage by holding positions on the fields along the river Bagradas, today’s Oued Medjerda. Scipio marched head-on, ready to meet the enemy in a pitched battle.

Scipio ordered his men to take the most traditional formation of Republican times: three lines of infantry, protected by two wings of cavalry. The first line were the hastati, young and fit soldiers to carry out the first clash with the enemy. The second line were the Principes, older legionnaires. Finally, the Triarii, the reserve of battle-hardened veterans who would join the fray at the time of need.

Scipio started the battle by launching his cavalry into action. With Laelius on the right and Massinissa on the left, they charged at Gisco’s horsemen. The attack was successful, and the Carthaginians retreated. Laelius and Massinissa continued the chase and when the dust settled, the flanks of Gisco’s infantry were completely exposed.

It was time to crush them.

The Principes and Triarii would normally fight in long, compact lines, supporting the Hastati. But now, Scipio had split them into smaller, agile maniples. This way, they carried out an enveloping maneuver, squeezing the enemies in a giant pincer.

Scipio had evolved Hannibal’s encirclement tactic into one that was much deadlier and quicker to execute.

Another Carthaginian army had been destroyed. This time, Gisco and Syphax had fallen captive. Nothing and nobody stood in the way of Carthage. There was nothing left to do for its Senate but start another round of peace talks.

During the winter of 203 and 202 BC, Scipio imposed conditions that respected the integrity and sovereignty of Carthage in its African territories. But Carthage had to recognise Massinissa as the sole King of the unified Numidians. The city had to withdraw its troops from Italy and abandon any plan to return to Spain. The Carthaginian Senate was also forced to disband the naval fleet and mercenary forces, and to pay an immense sum of 5,000 silver Talents to Rome.

The Winds of Zama

The peace negotiated with Carthage proved to be short-lived. A shipment of food supplies intended for the Roman army was blown off course by strong winds, and the triremes were beached near Carthage. Hungry citizens plundered the ships and refused to return their loot.

Scipio took the occasion to resume hostilities, devastating the farmlands around Carthage. Was he just looking for an excuse to continue the fight, until Hannibal showed up?

Well, his latest action did cause Hannibal to return. Before Scipio could strike at Carthage, Hannibal blocked his path by establishing a camp in Zama.

Hannibal’s remaining army matched the Romans in strength, at about 40,000 troops, plus he had the elephants. But he had less cavalry than Scipio, and he realised, perhaps too late, that Zama was not well supplied with fresh water. Hannibal could not endure a long standoff. He needed a way out.

His first initiative was to ask for a meeting with Scipio, to perhaps negotiate a truce, or resume talks for a definitive peace.

We don’t have an exact record of their meeting. What we know is that the two greatest Generals of their age showed the deepest respect toward each other. Perhaps Scipio was awe-struck by the older rival. And perhaps Hannibal was amused to meet a younger foe, who clearly considered him to be a master.

When Hannibal tried to propose a truce, however, Scipio was unmoved. He replied:

‘You failed to endure peace. You must now prepare for war.’

On October 19, 202 BC the Serpent and the Thunderbolt faced each other at Zama, the battle that would end it all, one way or the other.

Scipio had arranged his men in columns, leaving wide corridors between the maniples, and the gaps were covered by a line of light infantry.

Hannibal had placed his war elephants at the front, and he started the battle by unleashing them on the Romans.

This is exactly what Scipio expected. He ordered his front lines to bang their drums and blow their trumpets as loud as they could, producing such noise that frightened elephants stampeded back to the Carthaginians, decimating their front lines.

Some elephants continued their forward charge. This is when Scipio’s light infantry moved out of the way, revealing the gaps between the maniples. The elephants continued to charge along the corridors, doing little damage and eventually leaving the battle.

Now, Scipio took the initiative — he ordered Massinissa and Caius Laelius to attack the Carthaginian horsemen protecting Hannibal’s flanks. The Romans and Numidians had the better cavalry and were able to chase off their opponents.

Finally, it was time for Scipio to unleash his pincer and surround Hannibal. The Roman second and third lines of infantry moved out to the sides, ready to suffocate the Carthaginians with a mortal embrace.

But Hannibal had heard about the battle at the Bagradas, and he knew what to expect. As the Romans tried to move around their enemy, the Carthaginians spread out in a long line, preventing the encirclement.

The perfect countermove. Now it was just a long line of Roman infantry, opposite a long line of Carthaginians and allies. With cavalry out of the picture, Scipio’s infantry were outnumbered and could have quickly broken ranks.

But they didn’t. Those legionnaires were the veterans of Cannae, the former rejects turned heroes of the Republic. This was their occasion to avenge their defeat, and they would not back down.

Eventually, the Carthaginians started to lose cohesion. Some mercenary units tried to retreat, fighting their own allies to shove them out of their way. But the final blow came from Massinissa and Laelius: like an Easterly wind, their cavalries galloped back to the melee, striking at the Carthaginians from behind.

Hannibal managed to escape. But on that day, he left twenty thousand of his men on the ground, along with any remaining hope of saving Carthage.

Rome, and Scipio, had won the war.

Ungrateful Motherland

Publius Cornelius Scipio returned to Rome in triumph. He was now addressed as ‘Africanus’ thanks to his splendid victories in Northern Africa.

Scipio had negotiated a very good peace deal for Rome. Carthage retained its possessions in Africa, but it became a client state of the Roman Republic. Carthage would also pay an indemnity of 10,000 silver talents, renounce all but 10 of its naval vessels and all of the war elephants.

During his campaign, Scipio had also won a new ally to Rome, Numidia. And he had conquered a whole new province, Hispania, the first Roman-controlled territory outside of Italy.

Scipio was young, powerful, influential, and wealthy. His legions loved him, to the point of swearing allegiance to him, rather than Rome.

This aroused the suspicion of the Senate. To the more conservative senators, this man was dangerous. What could prevent him from declaring himself King and returning to the days of the Roman Monarchy? Rome was a Republic, and she intended to remain one.

The occasion to strike at Scipio came some years later.

In 194 BC, King Antiochus III of Syria was threatening the Greek city-states, which at the time were under Rome’s protection. His chief military advisor was none other than Hannibal!

Scipio at this time was strongly opposed by his most vocal political rival, Marcus Porcius Cato, better known as Cato the Elder. But the presence of Hannibal in Syria alarmed enough of the Senate to allow for Scipio to retake the position of Consul once again.

Scipio left Rome for a diplomatic mission in Greece, Syria, and Asia Minor. According to some sources, he had the occasion to meet Hannibal during the trip. The two chatted like old friends, talking history and strategy.

Scipio asked Hannibal who he thought were the three greatest strategists that ever lived. Hannibal replied:

“Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus, and myself”

Fair enough! Scipio had another question:

“But what would you have said if you had conquered me?”

Hannibal replied:

“I should then have said that I was greater than Alexander, greater than Pyrrhus, and greater than all other generals.”

The war with Syria eventually broke out, and Scipio joined in 190 BC as nominal deputy to his brother Lucius. Unfortunately, the two old foes did not meet again: Hannibal was in Phoenicia raising a fleet for the Syrians and had been pinned down by the navy of Rhodes, allied to Rome.

In January of 189 BC, Lucius Scipio defeated the Syrians in the Battle of Magnesia. His older brother Publius was away from the battlefield, recovering from an illness. But he was the victor, at least in spirit, as Lucius had used his tactics and commanded legions that he had raised and trained himself.

After Magnesia, King Antioch sued for peace, agreeing to a payment of 15,000 silver Talents to Rome. Of these, he paid an advance of 500 to the Scipios.

Africanus used this money for his private expenses … or maybe to pay his soldiers’ wages. This is still not clear. What mattered is that he had spent that money without asking permission from the Senate.

This was the occasion that Scipio’s rivals, fronted by Cato the Elder, were waiting for. He put the Scipio brothers on trial – twice! The first time, in 187 BC, Lucius was asked to produce the accounting ledger for the Syrian expedition, but Africanus intervened and tore it to pieces in front of the Senators. He then reminded them that he was being tried on the anniversary of his victory at Zama. The outcry was such that Cato contented himself with a mere fine to Lucius.

At the second trial, in 184 BC, Cato accused Scipio of embezzlement, corruption, and even of planning to become King of Rome with a military coup. This time, Cato was vetoed from further prosecuting the General by Senator Tiberius Gracchus the Elder. He would later marry Scipio’s only daughter, Cornelia.

Despite these victories in court, Scipio had grown disgusted with the Roman political class. He was not willing to serve the Republic anymore, and so he retired to his farm at Liternum, near Naples.

One day, a crew of pirates landed at Liternum, and the old General prepared to face them, weapons in hand. Soon, he realised the pirates had not come to burn and loot — they only wanted to meet the famous victor of Zama! Such was the fame of Scipio throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

In 183 BC Scipio must have heard the news that in the land of Bithynia, Hannibal had committed suicide by poison. He had been vilified for his defeat at Zama and forced to flee Carthage, serving foreign Kings while escaping capture by the Romans.

That same year, in 183 BC, the greatest General Rome had ever known succumbed to an illness. It was most likely malaria. Publius Cornelius Scipio ‘Africanus’ closed his eyes and joined many friends and enemies in the Elysian fields. In his will, he asked for his bones to be buried away from the ungrateful Rome.

Scipio’s legacy was enormous. His approach to strategy and innovative tactics revolutionized the armies of the Republic. His conquests launched the expansion of Rome beyond the confines of Italy. His defeat of Carthage made of the Romans a sea power, unrivaled in the Mediterranean, and the cult of loyalty among his men and legions created a precedent for the emergence of characters like Julius Caesar and Augustus. In short, the life and achievements of Scipio Africanus were a major turning point in which the history of the Republic became the downhill slope toward an Empire.

SOURCES:

A lecture by Prof Giovanni Brizzi (5 hour long, in Italian)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PktsN4lYtLM

Punic Wars and Scipio’s Strategy

https://www.ancient.eu/article/292/the-battle-of-zama—the-beginning-of-roman-conque/https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Publications/Article/1412483/scipio-africanus-and-the-second-punic-war-joint-lessons-for-center-of-gravity-a/

https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Cannae

Basil Liddell Hart’s biography on Scipio

Biographical summaries

https://www.heritage-history.com/index.php?c=read&author=haaren&book=rome&story=scipio

https://www.romanoimpero.com/2010/09/scipione-lafricano-205-204-ac.html

https://www.historynet.com/romes-craftiest-general-scipio-africanus.htm

http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/imperialism/notes/scipio.html

The Cursus Honorum

https://www.livius.org/articles/concept/cursus-honorum/