In 1922, Harry Truman sat in his mother-in-law’s house in small town Missouri, contemplating the failure that had been his life. He was nearly 40; behind him lay a string of failed businesses and unfulfilling odd-jobs. He was close to bankrupt, deeply in debt, and looked down upon by his wife’s elitist family. Aside from one brief stint in the Army, he had never lived outside his one horse town. He was, in short, a loser. A man who had failed at life so thoroughly even Jon Arbuckle would appear an overachieving Hercules next to him.

And yet, Truman’s luck was about to change. In a quarter of century, he would go from “small town nobody,” to “leader of the free world”. Another quarter of a century after that, and he’d be recognized as one of the greatest presidents in American history.

How did this happen? How did a man so singularly unambitious wind up achieving so many remarkable things? In today’s Biographics, we’re charting the strange and unexpected rise of Harry S Truman: the nobody who became a somebody.

The Boy from Nowhere

You know that old saying: “some are born to greatness, while others have greatness thrust upon them”?

Well, Harry Truman definitely falls into the latter category. Born on 8 May, 1884, Truman was a poor country boy through and through. His parents were of farming stock, scraping a living on the edge of the American frontier.

When Truman was aged just six, the family moved to Independence, Missouri, a small town on the banks of the river that acted as a gateway to the American West. It was in Independence that the railroads terminated, that the wagon trains set off. Even in 1890, people still had living memories of the settlers who had come through here, seeking gold and freedom.

They also had living memories of an altogether more controversial time.

When Independence was settled, it was mostly by families from the South. The town was racially segregated, and veterans who’d fought for the Confederacy were still kicking around. Like many growing up in that time, Truman absorbed the prejudices these men carried. For the rest of his life, he’d freely use racial slurs in private.

But if his fellow Missourians thought Truman was just another Good Ol’ Boy, they’d be in for a shock when he finally reached high office.

As he grew up, Truman went through all the usual pains we experience: he was often shy around girls, and sometimes found it hard to befriend other boys. But Truman’s childhood came with an added dose of misery. Aged 10, he contracted diphtheria, and spent the best part of a year with his arms, legs and throat paralyzed.

By the time he recovered, the frail, nearsighted boy had lost whatever interest he’d held in the outside world. The rest of Truman’s early years passed in a steady flow of disappointment.

He tried to become a concert pianist, but he lacked the drive. He applied to West Point to join the military, but his poor eyesight excluded him.

He enrolled in a Kansas City business college after high school, but family problems forced him to drop out after a single term. Back in Independence, his father’s farm was refusing to turn a profit. So Truman dutifully gave up on his dreams and sloped back home to help his Pa out.

He’d stay on that farm for the next eight years.

Perhaps the one gleam of light in these trying times was Truman’s relationship with his high school sweetheart, Bess Wallace. But even that turned sour. Wallace’s family disapproved of Truman’s background. When he proposed, she rejected him.

Come 1917, Truman was a guy so used to getting beat down by life that it’s a wonder he got out of bed in the morning.

So what saved him? What wild event plucked Harry Truman out of obscurity, and set him on the path to greatness?

For that, you can thank the wildest event of them all.

On January 19, 1917, German high command sent a message to Mexico. Known as the Zimmermann Telegram, it asked Mexico to join WWI by attacking the USA.

Not being idiots, the Mexicans were all like “err… NO,” and alerted Washington to Berlin’s absurd plan.

It was the beginning of the United States’ slow entry into WWI, a war that would ultimately kill over 115,000 Americans.

It was also Harry Truman’s ticket to finally escaping smalltown Missouri.

Life During Wartime

In late 1917, Truman’s National Guard unit was called up for basic training. Just before he left, Truman got a hastily scrawled message from a heartbroken Bess Wallace saying she wanted to marry him after all.

Truman’s response was as simple and as plain as his appearance:

“I don’t think it would be right for me to ask you to tie yourself to a prospective cripple—or a sentiment.”

And with that, his unit left Missouri. Military life suited Truman. He was promoted to captain, and took great pride in running the best canteen in his regiment.

But if you’re expecting to hear that Truman just stayed behind the lines and didn’t see action, prepare to be impressed. The unit shipped out in March, 1918. That August, Truman was thrown headlong into the meatgrinder that was the western front.

Through September and into October, he fought in the bloody Meuse-Argonne offensive – the only future president to see action in the Great War.

When he emerged on the other side, miraculously unscathed, Truman had gained his first experience at leading men. He’d also gained a friendship with a soldier named Pendergast.

Little did Truman know it, but his connection to Pendergast was going to change his life. Truman finally made it back to Missouri in May, 1919. One month later, he took Bess Wallace up on her offer, and the two of them married.

Not long after, Truman opened a men’s clothing store in Kansas City. It should’ve been the end of his adventures. A little project to occupy his postwar years.

No such luck.

In January, 1920, the sharpest, deepest depression in living memory walloped America.

Wholesale prices plummeted 37%, while the US was gripped by the worst single-year deflation on record. Business failures skyrocketed. One of those failed business was Truman’s clothing store.

In 1922, deeply in debt, Truman closed the store for good. Then he and Bess moved in with her parents, who never missed an opportunity to remind Truman of his failings. This is the moment we opened with. The moment when Harry Truman, aged nearly 40, took stock of his life and realized it had amounted to nothing.

However, fate was about to come knocking. Over in Kansas City, Tom Pendergast was looking for fresh meat for his political machine. The uncle of Truman’s wartime buddy, Pendergast was also the city’s Democratic boss, a guy who’d corrupted the entire state with his ruthless machinations.

But while he was corrupt, Pendergast also liked to use men who were personally honest, to give himself some cover. Men like his nephew’s WWI buddy, Harry Truman.

That same year, Tom Pendergast contacted Truman and made him an offer.

We don’t know the exact terms, but we do know that Truman was suddenly installed as the local judge of eastern Jackson county.

From there, the future president set about awarding fat contracts to Pendergast’s allies. But while Truman’s time with Pendergast was certainly dodgy, it wasn’t completely corrupt. Although he played the game, and did as his boss asked, Truman also took his new job seriously.

On Truman’s watch, local government in Jackson County became more efficient. It wasted less money. Truman himself was scrupulously honest, just as Pendergast had hoped.

In fact, Truman was such a good little cog in the Pendergast machine that, come 1934, Pendergast was ready to promote him. He asked the former farmer how he’d feel about becoming a senator.

And, just like that, Harry Truman found himself on his way to Congress.

The “Senator from Pendergast”

When Truman arrived in Washington on 31 December 1934, his past did not go unnoticed. Pendergast’s goons had stuffed the ballot boxes to get Truman through his Senate primary, and it was widely thought the new senator was just a puppet of the Kansas City boss.

Indeed, Truman’s nickname on Capitol Hill was “the senator from Pendergast”.

But Truman refused to take the bait. He carried on as he had in Jackson County – diligently, with great personal integrity. Had his Pendergast connection not been widely known, it’s unlikely anyone on Capitol Hill would’ve ever linked the two.

This soon turned out to be extremely fortunate.

In 1939, just as Truman’s first term was ending, the federal government came rolling into Kansas City. Tom Pendergast was arrested and jailed, and his political machine destroyed.

This left Truman in a precarious position. He’d only won his senate seat thanks to Pendergast. Did he have the political skills to win a second term by himself?

As it turns out, he nearly didn’t.

In the bruising 1940 primary, Truman squeaked the Democratic nomination for his seat by a mere 8,000 votes. That meant relying heavily on urban areas, including urban areas with large African-American populations.

From 1940 on, Truman would have a lasting reputation as a big city liberal.

Still, Truman was returned to Washington. This time, he was determined to make his mark. Truman’s first term had been marked by muted support of whatever was popular in Missouri, like FDR’s New Deal, or bills backing American isolationism. His second term, though, saw Truman suddenly become a vocal champion of rearmament.

It’s like Truman knew America was already destined to enter the war in Europe. And he was going to use that to his advantage.

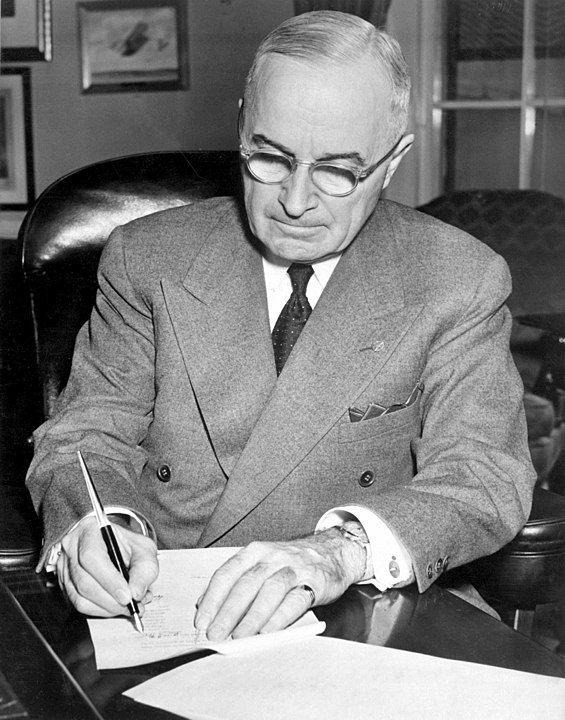

In March, 1941, Truman approached Franklin Roosevelt, then just embarking on his record-breaking third term.

Truman told the president that he was worried about the military wasting money, and recommended setting up a panel to investigate spending. FDR basically shrugged and said “sure, why not?”

That inauspicious start was how the Truman Committee was born.

Running from 1941 to 1944, the Truman Committee became famous across America. Like a superhero accountant whose superpower is being really damn good at accounting, Truman combed through every expense, noting every penny.

Over three years, he saved the government billions of dollars.

This had the not-so-subtle side-effect of separating him from his Pendergast past. Once the US entered the war in December 1941, Truman’s pen-pushing came to be seen as patriotism – ensuring money that would’ve been wasted went towards fighting Hitler.

The upshot was that Truman reached 1944 no longer known as the “senator from Pendergast” but as a respected centrist Democrat.

This was unbelievably good timing.

In 1944, the Democrats were trying to decide their ticket for the upcoming presidential election. While there was no doubt FDR would be the headline act, his current VP – a guy called Henry A. Wallace – was considered too left-wing to be allowed to run again.

So party bosses went to FDR and basically said: “look, we’re gonna replace Wallace. Deal with it.”

To which we love to imagine FDR saying something like: “sure, whatever. Now get outta my Oval Office. I’ve got a damn war to win!”

In that moment, the fates of two men were sealed. Henry Wallace was destined to be pushed out the corridors of power. And Truman…

Truman was suddenly destined to become president.

The Day the Stars Fell

The 1944 Democratic convention was unconventional to say the least. As party bosses descended on Chicago, Henry A. Wallace got wind of his replacement and began kicking up a huge stink. Truman, on the other hand, discovered that he was in the running to be VP, and did everything in his power to wriggle out of it.

But there was nothing he could do to stop his star from rising.

At the convention, the anti-Wallace faction was strong enough to bring the VP down, but too weak to get one of their own elected. So everyone settled on Truman as the compromise candidate. And finally, after two bruising days, the man from Missouri wound up on the ticket.

Absolutely no-one was happy with this.

Truman didn’t want to be veep; FDR didn’t want him to be veep; and everyone at the convention had someone else they’d rather see as VP. Yet it didn’t matter. Come November, FDR’s wartime record saw him handily beat Republican candidate Thomas Dewey, and suddenly Truman was vice president.

It was a role he’d hold for barely 80 days.

On the afternoon of April 12, 1945, Harry Truman was summoned to the White House. It was a curious order to receive. In his entire time as VP, Truman had barely seen FDR. Barely been let in on his plans for his fourth term.

As Truman arrived at the White House, Eleanor Roosevelt came out to meet him.

“Harry,” she said, “the president is dead.”

Truman later said he felt as if “the moon, the stars and all the planets had fallen on me.”

He collapsed into a big leather chair in the Cabinet Room, waiting for the Chief Justice to come and swear him in as president. As others arrived at the White House, the enormity of it all sank in. America was at war. Although that war was in its endgame, the political giant who’d guided the nation through its darkest hours was gone.

In his place was a smalltown man who, were it not for a quirk of fate, would right now be managing a men’s clothing store in Missouri.

One Cabinet member later recalled looking at Truman and thinking “he looks like such a little man.”

He didn’t mean in literal terms. At the press conference announcing Truman’s ascension to the presidency, people were shocked. One BBC journalist later recalled reporters saying “my God, what have we been landed with?”

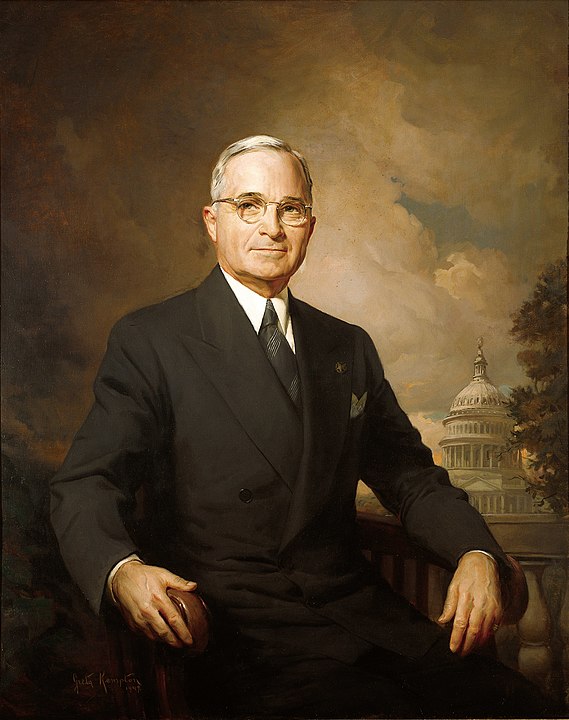

You could tell Truman was thinking along similar lines. That day, April 12, Truman became the 33rd President of the United States. Almost immediately he was thrown in at the deep end.

Truman’s first months in office were the kind prospective presidents have nightmares about. Barely had his first press conference ended than he was having to sign off on arrangements for the first-ever UN meeting in San Francisco.

Only weeks after that, he was desperately helping to arrange Germany’s unconditional surrender.

It was a whirlwind of work, overseeing the end of a war that had raged for years.

It was also about to get so much harder. Although Germany’s surrender had ended the war in Europe, the war in the Pacific was still raging. It wouldn’t be long before the new president was called upon to make the most controversial decision any president will ever make.

A New War

For as long as people talk about Harry Truman, they’ll talk about his decision to drop two atomic bombs on Japan. Was it a war crime, an atrocity? Or was it a proportionate response to a racist, militaristic nation that was refusing to surrender?

Whichever side you fall on, the basic facts are these. Faced with estimates of up to 500,000 dead in an invasion of Japan, Truman authorized nuclear strikes. On August 6, the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima, ending 80,000 lives.

The next day, Truman went on TV and declared that if the Japanese:

“do not now accept our terms (of surrender) they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

Two days later, the Fat Man bomb landed on Nagasaki, killing 40,000. On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. WWII was over.

But while one war was winding down, another was lumbering into view.

The following spring, 1946, Truman joined Britain’s wartime leader Winston Churchill onstage in Missouri. There, the former Prime Minister gave a speech in which he warned of an iron curtain “descending across the continent” of Europe.

Today, the Iron Curtain speech is seen as the opening salvo in the Cold War. Not only did it galvanize western opinion to the USSR, it also pushed Truman to make his own major speech.

On March 12, 1947, Truman stood before Congress and declared:

“I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures. I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way.”

It was the beginning of the Truman Doctrine, the American policy of containing Soviet expansion. And it would set the tone for the entire 20th Century.

One positive side effect came just a year later.

Secretary of State George C. Marshall proposed a pan to rescue Europe’s shattered economies, and Truman embraced it as a way to stop the Communist advance west. Signed into law on April 3, 1948, the Marshall Plan would totally rebuild Europe.

But the Soviets were all too aware of its secondary, anti-Communist aim. And they weren’t going to leave such a provocation unanswered.

On 24 June, 1948, the USSR suddenly blockaded all roads and rail lines into West Berlin.

At the time, some two million people lived there; an island of Allied rule amid an ocean of Soviet administration. In Washington, the hawks in Truman’s cabinet urged the president to declare war, to take the fight to the Soviets.

But, for someone who would garner a reputation as a warmonger, Truman was remarkably restrained.

He ordered supplies to be flown into West Berlin for as long as the blockade remained. Known as the Berlin Airlift, the operation would become one of the biggest logistical feats of the 20th Century. At its height, one plane was landing in or taking off from West Berlin every 30 seconds; bringing clothing, food, water, medicine, and basic supplies for an entire city.

It was a grand achievement, all the more so for not spiraling into WWIII.

But, by the time the Soviets lifted the blockade, in spring of 1949, there was no longer any doubting what was happening.

Any lingering hopes of a rapprochement with the Communists was over.

The Cold War was officially on.

“Dewey Defeats Truman!”

By rights, Truman should’ve ended his first term riding high. He’d overseen the end of WWII; helped rebuild Europe; overcome the Berlin blockade; issued an executive order desegregating the military; and made the US the first nation on Earth to recognize Israel.

But rather than a winner, Truman marched toward his first election a badly-damaged loser.

In 1946, the midterms had resulted in a Republican wave sweeping Congress. As the 1948 election approached, the Democrats’ liberal wing had jumped ship to campaign for Henry A. Wallace’s Progressive Party.

Upstairs, the party bigwigs had begged Dwight D. Eisenhower to replace Truman as the Democratic candidate.

Finally, the southern Democrats also abandoned the party to vote for Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrats.

As November 1948 approached, a victory for Republican Thomas E. Dewey seemed certain.

Never mind that Truman spent the fall doggedly riding trains from town to town across the nation, making fiery speeches decrying the “do-nothing, good-for-nothing Republican Congress.”

Never mind the vast crowds that turned up to Truman’s whistlestop tours, chanting “give ‘em hell, Harry!”

The polls all said Truman was toast. As the Chicago Tribune prepared its presses, the editors were so sure of a Dewey landslide that they printed front pages reading “Dewey Defeats Truman.”

We can only hope there was plenty of humble pie to go around that newsroom. On November 3, 1948, America awoke to the news that Harry Truman had won a second term. Not only that, he’d trounced Dewey. The Dixiecrats had collapsed. The Progressive Party was nowhere to be seen.

When Truman picked up a copy of the Chicago Tribune and waved it at reporters, a vast grin on his face, an iconic moment in politics was made.

Come January, Truman returned to the White House, following the first televised inauguration in history.

Immediately, he got to work transforming the country.

Or, rather, he tried to get to work.

Despite pulling off the political upset of the century, Truman found his hands tied in his second term by a Democratic congress that hated his guts. When he tried to pass his Fair Deal legislation, which would’ve brought in swathes of new social programs benefiting Africa-Americans, it got so watered down that there was almost nothing left.

But Truman’s second term was never fated to be remembered for its domestic agenda. Instead, it would be events on a peninsula over 11,000km away that decided how history saw Harry Truman.

On June 25, 1950, North Korean troops poured over the 38th parallel, invading South Korea. It was the beginning of the Korean War, a war that would kill millions, and leave scars that remain to this day.

It would also be the war that ended Harry Truman’s career.

And Then There Was Korea…

Few wars have ever been as costly and as pointless as Korea. WWI may have been a freak accident that blew up in everyone’s faces, but at least it had an outcome: the collapse of the old European order. Korea, by contrast, started with a Communist-backed state and an American-backed state facing each other across the 38th parallel…

…and ended with a Communist-backed state and an American-backed state facing each other across the 38th parallel.

The worst part was the chaos it took to get to this stalemate.

At first the North overran the South, leaving swathes of destruction in its wake.

Then Truman dispatched general Douglas MacArthur to Korea, and the US-UN force chased the North back across the 38th parallel and laid waste to their country. But then the Chinese got involved on North Korea’s side, and forced the Americans all the way back to where they’d started.

Cities were burned, massacres were committed, and towns bombed into oblivion.

But for Harry Truman’s legacy, only one thing ultimately mattered: the conduct of Douglas MacArthur. Although Truman had been the one to send MacArthur to Korea without waiting for Congressional approval, the general soon proved himself to be a loose cannon.

In early 1951, he started demanding America invade China, which would’ve sparked a full war across the Pacific.

With WWII only just over, Truman refused. They weren’t going down the road of endless devastation. For MacArthur, this was a chump decision, and he said so. Loudly. So Truman fired his ass.

And, well, that was about it for Harry Truman.

When he returned from Korea, MacArthur was greeted as a hero. Truman, by contrast, saw his polls tank. His favorability ratings dropped to 22 percent, lower than any other post-WWII president. Even Nixon at the height of Watergate didn’t fall that far.

Faced with numbers like that, Truman knew he had no choice but to prepare his retirement.

Although the 22nd amendment had now been passed, limiting the president to two terms, an exception had been made for Truman as the sitting president.

In another context, Truman might have gone for a third term, might have tried to match FDR. But with the public against him, what was the point?

Truman bowed out the Democratic primary in March, 1952. That November, Eisenhower led the Republicans to a landslide victory, even carrying some southern states.

When Truman left the White House in January, the country was glad to see him go.

Only, that wasn’t quite the end of the story.

After his second term, Truman retreated back to Independence, Missouri, and set about tending to his legacy. He always said he’d “done his damnedest,” even when he was unpopular. Over time, people came to believe him.

Maybe it was the legacy of his Fair Deal, which wound up being enacted in another form by Lyndon B. Johnson. Maybe it was the memory of the man who’d ended WWII; or his undoubted touch with the common people; or his commitment to civil rights even in the face of his party’s southern wing.

Whatever the reason, Truman lived long enough to see his legacy rehabilitated.

It was all he could have asked for.

On Christmas Day, 1972, Harry Truman slipped into a coma. He died the next day, aged 88. Today, Truman consistently ranks as one of the best presidents in US history, in the same league as Teddy Roosevelt or FDR.

For a man once seemingly destined to small town obscurity, this is remarkable. Not even Truman thought he had what it took to lead his nation. And yet, when the time came, he stepped up and proved the world wrong.

All too often, making videos about the lives of great people involves talking about brainboxes, or the privileged, or people with charisma to spare.

But Truman’s story shows that you don’t need any of that. You can be a 40-year old failure from nowhere, and still wind up changing history.

Some men may be born to greatness, and some may have greatness thrust upon them. But it’s arguable that none of them will ever be quite as great as Harry Truman: the accidental president.

Sources:

Interesting British obituary from 1972, lots of good details: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5QfvDzm52nt86JBynD0dbZC/president-truman-30-december-1972

Excellent in-depth overview from the Miller Center (multiple chapters): https://millercenter.org/president/truman/life-before-the-presidency

Interesting NYT review of a book on Truman: https://www.nytimes.com/1992/06/21/books/work-hard-trust-in-god-have-no-fear.html

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Harry-S-Truman

Official White House synopsis: https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/harry-s-truman/

Truman Library: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/museum/presidential-years/introductory-film

Meuse-Argonne offensive: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/meuse-argonne-offensive-opens

1920 depression: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-depression-that-was-fixed-by-doing-nothing-1420212315

Tom Pendergast and the Pendergast Machine: https://pendergastkc.org/article/decline-and-fall-pendergast-machine

Truman and the Iron Curtain speech: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/churchill-delivers-iron-curtain-speech

Marshall Plan: https://www.britannica.com/event/Marshall-Plan

1948 election: https://www.history.com/news/dewey-defeats-truman-election-headline-gaffe

Berlin airlift: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/berlin-airlift-begins

Presidents ranked: https://www.c-span.org/presidentsurvey2017/?page=overall

Truman on race: https://apnews.com/ab0d537a112c3554373a97dff54c0e60