In 1298, a manuscript was published that took Western Europe by storm. Known today as the Travels of Marco Polo, it detailed the Venetian’s adventures in Asia – from India, to Japan, to Sri Lanka. Impressive as those tales were, though, it was the figure at the heart of Book Two who really set Europe alight. The wise, ancient emperor who ruled a China so wealthy, so enlightened, that it seemed like Heaven on Earth. That great emperor’s name was Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan Dynasty and grandson of Genghis Khan. He would go down as one of the greatest rulers in Asian history.

At the time of Marco Polo’s visit, Kublai Khan sat at the head of an empire so big, it defies comprehension. A Mongol warrior trained from birth in the art of war, he’d nonetheless grown into an emperor who valued Buddhism, science, and progress above conquest. A towering figure in both the Western and Chinese imagination, this is the story of Kublai Khan: the Mongol warrior who became a Chinese emperor.

The Great Khan

When you hear the name Kublai Khan, we’re guessing you also hear the incredibly famous opening of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem:

“In Xanadu did Kubla Khan, a stately pleasure dome decree.”

Aside from being two of the most-famous lines in English, they also perfectly sum up the Western vision of the emperor: a semi-mythical aesthete living a life of unparalleled elegance. Which means it can come as a shock to realize Kublai Khan wasn’t born in a grand palace and didn’t spend his life swanning around in silk pajamas.

No, when Kublai first opened his eyes on September 23, 1215, the sight that greeted him wasn’t the rarefied air of the Chinese imperial court…

…but the mud and din and savagery of the Mongol Empire.

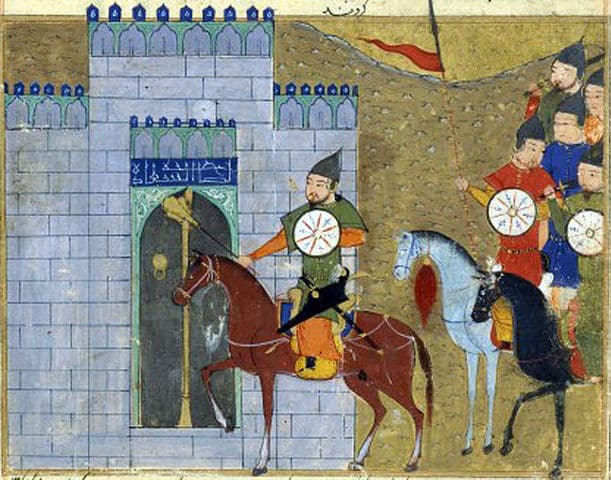

Just nine years earlier, Genghis Khan had united the rowdy, drunk nomadic herders of the Mongolian steppe into a rowdy, drunk army that was nonetheless one of the most-effective fighting units on Earth. Although the empire’s early days had been marked by forward-thinking policies like banning the kidnapping of women, that progressivism had quickly given way to conquest.

In 1209, Genghis Khan invaded the neighboring Xi Xia Kingdom, beginning the process that would lead to his descendants controlling the largest contiguous empire in history. By the time Kublai was born in 1215, Genghis had flattened the Xi Xia, crushed the Jin Dynasty, and captured Zhongdu – the city we’d now call Beijing.

We mention this because Kublai wasn’t just some random kid born to some random Mongol.

Kublai’s father was Tolui, the youngest son of Genghis Khan.

Well, the youngest legitimate son. Given that one in 200 men today are direct descendants of Genghis Khan, we’re guessing there were quite a few illegitimate younger sons out there. Now this didn’t mean Kublai grew up bouncing on Genghis Khan’s knee as he conquered the world.

In fact, Kublai barely saw his grandpa or his father. Instead, he was mostly raised by his mother, the Christian princess Sorkhotani Beki.

This meant a somewhat unusual upbringing by Mongol standards.

For one thing, Sorkhotani was a ferociously intelligent woman, and taught Kublai and his brother Möngke to read at a time when literacy came a distant second to being able to bring down an antelope. For another, she also made sure to expose her boys to Chinese culture and philosophy.

The impression this made on Kublai was so great, it would eventually change the course of Asian history.

Still, Kublai wasn’t a pampered little prince. Before he was 10, he was a formidable horseman, hunter, and fighter – all things the Mongols needed if they were to keep on conquering.

And conquering was by now what the Mongols were all about.

When Kublai was just five, the Central Asian Khwarezm Empire made the fatal of insulting Genghis Khan.

By the time Kublai was ten, Khwarezmia had fallen, leaving the Mongols in charge of an empire that stretched from the Sea of Japan to the Caspian Sea – a distance similar to that separating Memphis, Tennessee from Honolulu.

Little did young Kublai know it, but that empire was about to fall into his family’s hands.

On August 18, 1227, Genghis Khan died of injuries sustained falling off a horse. In the aftermath of the great Khan’s death, control of the empire briefly passed to Kublai’s father, Tolui.

It was the family’s first brush with immense power.

It certainly wouldn’t be their last.

The Age of Expansion

In the wake of Genghis Khan’s death, a kuriltai, or great gathering of Mongol leaders was called.

There, the decision was made that Tolui should hand control of the empire over to Genghis’s other son, Ögedei.

This was something of a weird choice.

Ögedei was a guy so dedicating to drunkenness that, when other Mongol leaders ordered him to cut down to just three cups of wine a day, he started drinking from cups roughly the size of bathtubs. He also had no practical experience of conquering. What Ögedei did have, though, was an ability to delegate. His view of the empire was:

“You can conquer an empire on horseback, but you cannot govern it on horseback.”

So, while great generals like Subutai were sent West to keep conquering, anyone with a more civilized bent of mind stayed home to keep things in order.

It was this philosophy that led to Kublai getting his first practical experience of ruling.

In 1236, Ögedei granted Kublai a fiefdom of 10,000 homes in modern Hebei.

At first, the 21-year old Kublai was all like “booooooooooorrrrrrrrring.”

He ignored his duties, sending agents to do all the burdensome stuff like collecting taxes. Unfortunately, these agents were exactly as competent as you’d expect a bunch of Mongol raiders to be, and the twin threats of taxation and terror soon left Kublai’s province almost empty.

It was only at the end of the decade that Ögedei seems to have told Kublai, “dude, use that province or lose it,” and Kublai finally started acting like a ruler.

But while the role may have been forced on him, there’s no doubt he excelled at it.

With Kublai now on the scene, all those incompetent tax collectors were fired, and replaced by experienced Chinese officials. At the same time, Kublai began consulting Chinese advisors more and more. Although they were just a part of his local court – a court that also included Christians and Muslims – they soon edged the other voices out.

It seems that Kublai just couldn’t get over his childhood fascination with all things Chinese. For the other Mongols, this was shocking. Who would voluntarily exchange manly Mongol traditions like hunting and fighting for wussy Chinese ones like tea and reading?

But Kublai wasn’t to be deterred. He became interested in Buddhism, began to appreciate Confucianism – including the revolutionary idea that the well-being of an empire’s subjects was just as important as that of its rulers.

Still, these interests seemed laughably irrelevant to other Mongols.

The empire was currently pushing into Europe, the unconquered south of China forgotten about. What need would the Mongols have for pretentious Chinese guff now?

Yeah, about that.

On December 11, 1241, Ögedei died of a stroke.

At that precise moment, the Mongols were laying waste to Eastern Europe. Kyiv had been sacked, Krakow put to the sword, and raiding parties were knocking at the gates of Vienna. Then word arrived of Ögedei’s death, and the conquerors simply turned around and went home.

At least, that’s the story. Some historians think the retreat was sounded for other reasons, and Ögedei’s death was just a convenient excuse.

Whatever the truth, the upshot was that Europe was forgotten about while the messy issue of Ögedei’s successor was sorted. After a few years of quarreling, it was eventually decided that Kublai’s older brother, Möngke, should be great Khan.

And Möngke was a guy as obsessed with China as Kublai.

From now on, the Mongol focus wasn’t gonna be on rampaging further and further into Europe…

But on conquering the last independent parts of China.

In Xanadu…

No sooner had Möngke been declared great Khan than he gave Kublai two very important things.

One was Northern China.

Yep, the Mongol Empire in 1251 was so vast that Möngke could basically gift half of China to his brother and say “hope you like!”

The second was an order, one designed to test Kublai’s mettle. Möngke wanted Kublai to conquer the Dali Kingdom. At this point, Kublai had never run a military campaign, and there was no guarantee he wouldn’t turn out to be the Mongol equivalent of Mister Bean.

It took Kublai a whole year to prepare to fight the Dali. A whole year in which he practiced tactics, and read great Chinese thinkers on the arts of war.

Finally, in 1253, Kublai saddled up, got his army together, and rode into the Dali Kingdom.

The conquest took three years. But it wasn’t three years marked by the usual Mongol atrocities. Kublai by now firmly believed what his Chinese advisors had taught him about a ruler’s codependence with the ruled. Which meant not killing new subjects during conquest, but treating them with mercy.

For the Mongols, this was seriously cuckoo stuff; like if a modern general suggested his army tried replacing its bullets with Black Forest gateau.

But Kublai was serious. Terror was to be toned down, and pillaging was out.

And so a new era of Mongol warfare was born.

Nicolas Sanson – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

By 1256, the Dali Kingdom had fallen. Buoyed by his brother’s success, Möngke began planning an invasion of southern China, where the Song Dynasty still held out. But such an undertaking required time, time in which Kublai wasn’t just gonna park his thumb up his ass and wait for his brother to say “go”.

So Kublai left Dali and returned north to embark on his most-famous project of all.

Xanadu is legendary in the English-speaking world. Although this is mostly due to Coleridge’s poem, it deserves the hype.

Kublai’s new capital was designed on Chinese principles of feng shui, perfectly placed in relation to mountains and rivers, between the agricultural lowlands and Mongolian steppe. Great walls and towers enclosed a city of 200,000 people, all laid out on a classic Chinese square plan.

At its heart sat a palace almost beyond imagination, a “stately pleasure dome” complete with its own hunting grounds.

It was an expression of Kublai’s love for Chinese style… but also of his power.

Power that was growing by the minute.

In 1258, Kublai invited leaders of both Buddhist thought and Daoism to Xanadu for a grand religious debate. There, he listened to both sides, before eventually declaring that Buddhism had won and making it Northern China’s official religion.

It a decision that would play a huge part in Buddhism’s spread across East Asia.

But as Kublai’s stature grew, Möngke began to take notice.

The same year as the religious debate, he sent agents to Xanadu, who began purging Kublai’s Chinese advisors on trumped-up charges. For a moment, it looked like there could be civil war between the brothers.

But Möngke backed off at the last moment, realizing he needed his brother for the coming fight against the Song. They patched things up and, in 1259, finally invaded southern China. Sadly, though, the civil war hadn’t been stopped. It would now just take place between different siblings.

On August 11, Möngke died while besieging a Song city.

Immediately, two candidates for his successor presented themselves. Up in Mongolia proper, Kublai’s younger brother Arigböge was at the head of a conservative faction, displeased with Möngke’s China war.

Down in the south, there was Kublai, even now fighting the war his brother had so long dreamed of.

There was only one way a Khan could ever be chosen between the two siblings.

They were going to have to fight.

The Wrath of the Khan

If anyone ever had any doubt about Kublai’s ambitions, they were quickly dispelled after Möngke’s death. As soon as he could, Kublai made a peace treaty with the Song. Then he quick marched back up north to Xanadu and, on May 5, 1260, called a kuriltai.

It ended with Kublai being elected great Khan and a proclamation drawn up in classical Chinese.

But while Kublai’s meeting had named him leader, this wasn’t the same as him actually leading the Mongols. Up in Karakorum, Arigböge responded to the news by essentially going “oh, yeah?” and holding his own kuriltai which named him great Khan.

It was a stalemate. Kublai now controlled the biggest, richest part of the empire, while Arigböge ruled the homeland.

It’s arguable that this stalemate was never really resolved.

Although Kublai defeated Arigböge’s forces in 1264, the north of the empire remained out of his control. The conservative faction replaced Arigböge with a guy called Kaidu, and Kaidu basically just did his own thing, like he was separate from Kublai’s empire.

It’s around this point that we can stop thinking of the Mongol Empire as a single entity, and more like the collection of Khanates it would eventually become.

Still, nominal control of the homeland was good enough for Kublai. Arigböge defeated, he went straight back to war with the Song Dynasty.

It was a hell of a fight.

Although only in control of southern China, the Song could still call up an army of one million men. They had gunpowder, catapults, siege engines. A navy with the biggest ships in human history. It was a fight Kublai had no guarantee he could win. So why did he bother?

The reason was simple. Kublai didn’t just want to make the Song submit.

He wanted to reunify China.

Prior to Kublai Khan, the last time China had been unified had been under the Tang Dynasty, who’d fallen 360 years before. To give you some idea of how ridiculously long ago that was, traveling back in time 360 years from today would land you in 1660.

In 1660, Oliver Cromwell had only just died. New York was still New Amsterdam. Louis XIV was on the French throne. Kublai’s dream of reuniting China was like you meeting someone today who dreams of returning the Thirteen Colonies to England. It was mad, laughable.

It was also something he totally succeeded at.

By 1271, Kublai had established a new capital at modern-day Beijing, and renamed his empire in the Chinese style, declaring it the Yuan Dynasty.

By the mid-1270s, Song generals were defecting, swearing allegiance to the new Yuan emperor. At last, on March 28, 1276, the boy emperor of the Song was captured and taken as prisoner to Beijing.

Although Song loyalists would fight on for three more years, the writing was on the wall.

The final end came on March 19, 1279.

On that day, a titanic naval battle took place near modern Macu. When it was finally over, there was no-one left to oppose Kublai Khan. Aged 63, the great Khan had at last finished his brother’s work. China was now conquered, reunified, and at the mercy of the Mongols.

Only, the other Mongols didn’t quite see it that way.

In the course of the conquest, Kublai’s Yuan Dynasty had begun to take on more and more Chinese characteristics, until it seemed completely alien.

No-one knew what was coming next, but they may have agreed on one thing.

Whatever form Yuan rule took, it certainly wasn’t going to be Mongol in nature.

A Traveller from an Antique Land

In 1275, three bedraggled men arrived at Kublai’s Khan’s vast marble palace. They came from the distant city of Venice, over 7,500 km away. The older two were merchants, while the younger was a lad of barely twenty with a gift for languages.

They’d come intending only to stay a short while. But when the Khan saw them, he was so impressed with the youngest that he made them stay for 16 whole years. The name of that young man? As you’ve already guessed, it was Marco Polo. And it’s his account of Kublai’s court that still forms the basis of how we see the Yuan Dynasty.

By the time Polo presented himself to the great Khan, the growing empire was already in full swing.

Under the Yuan, China entered a period of incredible prosperity, but one that wasn’t quite the uncomplicated picture of perfection that Polo painted.

On the good side, Kublai was a ruler who was seriously into innovation. Under his watch, everything from an empire-wide postal service to the issuing of paper money was established.

But Yuan China wasn’t just about physical improvements. Kublai was also a leader in innovative thinking.

Freedom of religion was embraced. Any language from around the empire was permitted at court, and Kublai even hired a team to create an artificial language which would bind his subjects together – although this never caught on.

There were scientific advances, too. Kublai had accurate maps made of China, established institutes of medicine, and improved the calendar.

He also turned Chinese society on its head.

Under the Song, artisans and doctors had been discriminated against as useless idiots who spent time doing stuff with their hands rather than refining their minds with Confucian poetry. But Kublai flipped that. He handed artisans enormous tax breaks, promoted doctors and astronomers.

The result was an economic boom that dragged reunified China into the new era.

But Kublai’s outward successes masked some deeper failures.

One was a state policy of racial discrimination.

While Kublai played the part of the Chinese emperor, wearing traditional robes and allowing himself to be carried around by servants, the reality was that his China was deeply discriminatory towards Chinese. The Yuan had four social classes. At the top were Mongols, who held all the key posts. Second were useful foreigners, like Marco Polo or the Khan’s Muslim treasurers.

Third were northern Chinese, who shouldered a heavy tax burden. And fourth were the southern Chinese, who were considered lower than vermin.

The result was millions of Chinse crushed by taxes, and treated like strangers in their own land.

On a personal level, too, Kublai wasn’t quite the serene emperor of popular imagination. The Khan drank like a fish, ate like a pig, and screwed like a rabbit. The result was that he eventually transformed into a fat, gout-ridden, horny blob prone to outbursts of temper.

And yet, for all these faults, there’s no doubting Kublai’s legacy.

In Chinese official historiography, the Yuan era is regarded not as an Interregnum, but as part of the imperial story – an honor only afforded to one other foreign dynasty: the Qing. But while Kublai’s rule at home might be complicated, there’s no such shades of gray regarding his foreign policy.

That’s because his time as emperor was taken up not with being a great administrator, a powerful warrior, or even a champion drunk…

…but with an endless series of disastrous wars.

The Other Great Khan

One of the most-interesting things about Kublai is that there always seem to have been two people in his head, fighting for control. One was Kublai the Yuan Emperor, who wanted nothing more than to follow his childhood obsession with all things Chinese, and settle down as a wise ruler.

The other was Kublai Khan, the Mongol warrior, who felt his life should be taken up with conquest.

Sadly for Kublai’s prosperity, in his later years it was Kublai the warrior who won out. We say “sadly” because, despite his early-life victories against the Dali, the Song, and Arigböge, late-life Kublai was a real putz when it came to conquering.

There were his two invasions of Japan, in 1274 and 1281, which both times resulted in typhoons wrecking his entire navy – an incident which led to the Japanese concept of the “Divine Wind” or kamikaze. There were his two invasions of Vietnam, and his two invasions of Burma, both of which resulted in Pyrrhic victories thanks to their sheer, insane cost.

Finally, there was Kublai’s 1292 invasion of Java, which ended with the victorious Mongols so riddled with disease that they were forced to retreat after a single year. It was a disappointing end to a dizzying career, like riding a rollercoaster that reaches its highest peak only to suddenly shut down and leave you stuck and disappointed.

But it’s likely that, by the time of the Java disaster, Kublai no longer cared.

In 1281 and 1285, the Yuan emperor had lost first his favorite wife and then his eldest son. This one-two punch of tragedy seems to have floored Kublai, who withdrew from the day-to-day running of the empire, instead drowning his sorrows in drinking and feasting.

By the time he finally allowed Marco Polo to leave his court, the one-time warrior was nothing but a fat, unhappy man, trapped in a vast palace as luxurious as it was empty. Kublai Khan finally died on February 18, 1294. His body was buried in a secret place somewhere in Mongolia.

As with his grandfather, Genghis Khan, his remains have never been found.

In the years after Kublai’s death, two important things happened that would ensure his place in history. The first was that Marco Polo’s book appeared, forever fixing an image of the Khan as a wise and benevolent ruler.

The second was the collapse of the Yuan Dynasty.

Although Kublai’s descendants ruled China peacefully for 30 years, in 1324 a series of uprisings marked the beginning of the Dynasty’s decline. Come 1368, the Yuan were so weak that the Ming were able to conquer China and establish their own dynasty. In the aftermath, the Mongols retreated back to the steppe, never again playing an important part in history.

But the same can’t be said of Kublai Khan.

In 1644, the Ming in turn fell to Manchu invaders: the Qing.

As the new masters of China, the Qing looked back to the last foreign dynasty as their inspiration; as the golden age they hoped to emulate. In the story of Kublai Khan, they found the template for their own Dynasty – a Dynasty that would last until 1911.

Today, Kublai’s name still survives – less as that of an historic figure, and more as a byword for something romantic, poetic and mystical.

Yet even this is more than than that afforded to any other Mongol leader apart from Genghis Khan. More even than perhaps any other Chinese emperor.

Kublai Khan the man may be long dead, but the stories of his exploits, the influence his life had on others, ensure that his name will live on forever.

Sources:

Biography’s succinct overview: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/kublai-khan

History’s take: https://www.history.com/topics/china/kublai-khan

BBC profile: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19850234

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Kublai-Khan

ThoughtCo: https://www.thoughtco.com/kublai-khan-195624

Ancient.eu: https://www.ancient.eu/Kublai_Khan/

Timeline of Mongol Conquests: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mongol_Empire_map_2.gif

Life of Genghis Khan: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Genghis-Khan

https://www.history.com/topics/china/genghis-khan

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43991/kubla-khan

Ögedei Khan: https://www.ancient.eu/Ogedei_Khan/

UNESCO inscription of Xanadu: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1389/

Marco Polo’s life: https://www.biography.com/explorer/marco-polo

Genghis Khan’s genetic legacy: https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/1-in-200-men-direct-descendants-of-genghis-khan