Who do you think of when you hear the words “father of the atomic bomb”? We’re guessing it’s Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Manhattan Project who famously responded to the first A-Bomb test by declaring “now I am become Death, destroyer of worlds.” But what if we told you there was another contender? A scientist who came this close to making the big breakthrough in 1934… a breakthrough that could have resulted in Nazi Germany developing the world’s first nuclear weapon. The scientist who almost created this terrifying alternative reality was Enrico Fermi, the godfather of the atom bomb.

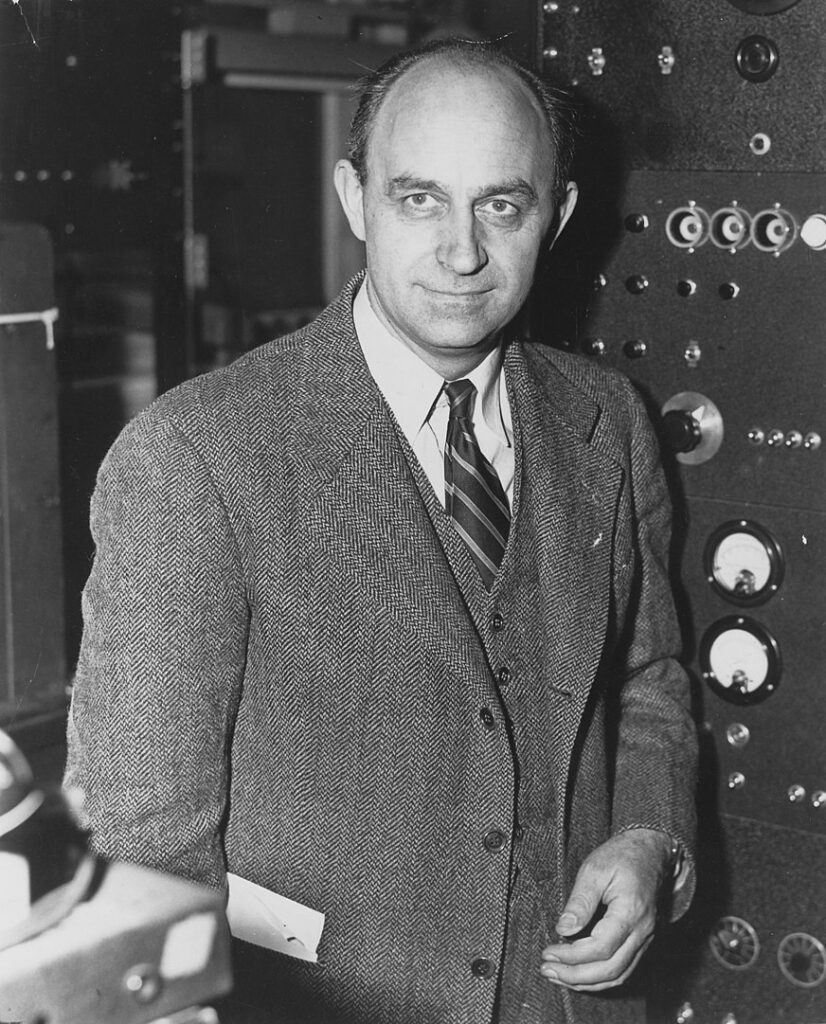

A leading light in both experimental and theoretical physics, Fermi was an almost once-in-a-generation genius. It was Fermi who built the first operational nuclear reactor in 1942, Fermi who created our understanding of the subatomic particles known today as fermions, and Fermi who helped Oppenheimer father the Bomb. From fascist Italy to WWII America, this is the life of Enrico Fermi, the greatest Italian scientist this side of Galileo.

The Quiet Italian

One of themes we’ve touched on, time and again is that – despite what fiction tells you – you usually can’t tell which child is gonna grow up to change the world. Otto von Bismarck, for example, was lazy as a kid. Mathematician Emmy Noether was going to be a language teacher. Johannes Kepler was obsessed with joining the priesthood.

But there are times when even real life follows the rules of fiction. Times when you really can just look at a child and think “that kid’s gonna be world-famous one day.”

Enrico Fermi was one of those kids.

Born in Rome on September 29, 1901, Fermi came from an average family. His father was a government railway inspector, while his mother Ida was a teacher. But Ida was above average in one very particular way. She believed acquiring knowledge was almost a sacred duty.

You might say this was the closest thing to a religion in the Fermi household. Unusually for the time, the family weren’t Catholic, and sent young Fermi to one of the few secular schools in Rome.

There, aged only six, Enrico Fermi began to show signs of the genius he would become.

Basically, from the moment he started school, Fermi was consistently at the top of his class. Ida had instilled in him a deep love for math, science, engineering, and everything else brainy. When not studying, the boy spent his time building electric motors with his older brother Giulio.

So, yeah, if you’d been introduced to child Fermi circa 1910, you’d have probably thought to yourself “that kid’s gonna be big.”

But you might not have guessed he’d be big in the world of physics.

That’s because it’d take a tragedy to set Fermi on that particular path. In January, 1915, Fermi’s brother Giulio went into hospital for routine surgery on a throat abscess. Something went wrong, and he died on the operating table, bleeding out aged only 15. For the teenage Fermi, this was like God had just cruelly hurled a lightning bolt right into the middle of his life.

As a boy, Fermi had always been shy and introverted. But in the wake of Giulio’s death, he became almost catatonically withdrawn. Frightened, Ida tried to convince her son to lose himself in his studies. She found a fifty year old book on physics, and gave it to the boy to read.

What Fermi read there blew his young mind.

There was something about the world described in that book that just made sense to Fermi, that made him want to learn more. From that point on, the boy wouldn’t be a magpie, leaping from one STEM subject to the next.

His mind would instead be a high-powered laser, focused solely on physics. In 1918, three years after Giulio died, Fermi applied to the prestigious Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa.

On November 14 that year he sat the entrance exam.

The task was to write a competitive essay. Fermi chose the topic Characteristics of Sound. When the examiner read it, he nearly fell off his chair. While anyone sitting this exam was naturally intelligent, Fermi was at a whole other level. He’d turned in a paper that would’ve been impressive for a doctoral thesis.

Fermi was instantly fast-tracked onto the school’s doctoral program, with his advisor the director of the physics laboratory. But the director soon realized this kid was such a natural that it was impossible to teach him stuff.

In just three years of self-study, Fermi had become so good at physics that he could run rings around a department chair.

Everybody at the school could agree on one thing.

They couldn’t wait to see what he did next.

Breaking Italy

At the same time Fermi was rising through the physics profession like an out of control weather balloon, another Italian also found himself being catapulted toward stardom. On March 23, 1919 – mere months after Fermi sat his exam – Benito Mussolini founded the Fascist Party.

Although neither Fermi nor Mussolini could’ve known it at the time, their lives were destined to cross in a way that would change history. Within a year of the Fascist Party’s appearance, chapters had sprung up across the nation, and whole regions descended into violence.

Mussolini was a world class rabble rouser, a guy who could whip up a mob in the time it takes to boil an egg.

As his influence spread, blackshirt militias began attacking leftists, burning down trade union offices, and physically stopping leftwing officials from taking their posts.

Come July, 1922, the whole of Italy knew Mussolini’s name, and either loved or loathed him.

With possibly one exception.

All his life, Enrico Fermi would be staunchly apolitical, never showing the slightest hint of interest in politics. As Italy fell into chaos that summer, he was likely thinking of one thing only: defending his thesis. By now, Fermi had already published his first couple of papers, and his planet-sized brain was infamous across Pisa.

When he actually came to defend his thesis before 11 examiners, it’s said only two of them were capable of grasping what he was talking about.

Fermi graduated with honors, almost immediately receiving a government grant to continue his studies.

Not that that government would be around much longer.

That same summer, Mussolini’s blackshirts smashed a general strike called by Italian leftists. On 24 October, before a gathering of 40,000 fascists, Il Duce declared that the government was incapable of governing, and that his party would physically remove it from power.

Mussolini’s March on Rome was the moment democracy died in Italy.

Faced with an insurrection, the government collapsed. Preferring fascism to anarchy, King Victor Emmanuel III invited Mussolini to form a new government. On Halloween that year – a fitting date if there ever was one – Italy’s balder, fatter version of Hitler became Prime Minister, the first fascist leader in history.

But while life was about to take a bad turn for Italy in general, it was taking a series of extremely good turns for Enrico Fermi. Between 1922 and 1926, Fermi won a series of scholarships, going abroad to teach in Germany and the Netherlands.

By the time he settled back in Italy in 1926, he was ready to change the world.

Offered the chair of theoretical physics at the University of Rome, aged just 25, Fermi made breakthrough after breakthrough.

Perhaps his most lasting was the development of what are known as Fermi-Dirac statistics – basically a way of understanding a group of subatomic particles that would otherwise make us go “whaaaaaaaaa-?” every time we thought about them.

In fact, Fermi was so prolific, and his intuition so often accurate, that his colleagues started calling him “the Pope” of physics. But it wasn’t just Fermi’s colleagues who were paying attention to his extraordinary mind.

In 1929, Benito Mussolini – now absolute dictator of Italy – personally appointed Fermi to the Accademia dei Lincei. The apolitical physicist was given a huge salary, a uniform to wear, and the title of “excellency.” All he had to do in return was bring glory upon Mussolini’s Italy by making more breakthroughs.

Scarily, that’s exactly what happened.

In his new post, Fermi would soon come terrifyingly close to giving Il Duce the key to the atom bomb.

Fathering the Bomb

The next few years were crazy-busy for Fermi. In 1928, he married Laura Capon, daughter of a respected Jewish family, with whom he’d have two children.

In 1930, he made his first visit to America, where he lectured on quantum theory.

Shortly after, Fermi seems to have decided the quantum field was becoming exhausted. He switched his focus to nuclear physics.

It was this switch that would lead to his big breakthrough.

In 1934, Fermi and his team were researching the atom. They’d already discovered that pretty much every element is capable of nuclear transformation, and were now focusing on uranium. It was while working with the element that Fermi discovered the first step toward nuclear fission.

Since we’re a history channel rather than a science channel, we’re not qualified to go deep into this.

But the basic gist is that Fermi made a breakthrough, from which any garden-variety genius could’ve deduced other breakthroughs could be made, eventually leading to everything from nuclear reactors to A-Bombs.

As the 2016 book The Pope of Physics notes, had Fermi’s brain been firing on all cylinders at that time, it’s likely nuclear fission would’ve been discovered in Italy in 1935.

One possible consequence? Nazi Germany using that research to acquire nuclear weapons.

It’s a scary thought that out there, just a few degrees away, sits a parallel universe where the London Blitz was not a sustained campaign, but a single bomb, falling from the sky, that turned the British capital into rubble in a flash of light.

Luckily, we don’t live in that universe.

In our universe, Fermi’s brain – for some reason – wasn’t quite operating at full capacity. He merely thought he’d created a new element; one the press argued should be named after Mussolini. By the time everyone figured out what was actually going on, any headstart Nazi Germany could’ve got on the Bomb was gone.

In terms of near misses, they don’t get much nearer than that.

Still, Fermi’s work was important, important enough for him to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1938.

And that’s today’s second stroke of good luck, because 1938 was when everything went to hell. That summer, Mussolini suddenly brought in a raft of anti-Jewish laws.

So extreme were these laws, so nakedly modeled on Hitler’s, that they penetrated even Fermi’s physics-addled mind.

Although he was staunchly apolitical, Fermi couldn’t ignore the fact that these new laws targeted his wife; and probably their children.

Unfortunately, the new laws also made it impossible for Jews to leave Italy without a very good reason. A reason like, oh, I dunno… winning the Nobel Prize?

That December, Fermi traveled to Sweden to collect his Nobel Prize for Physics.

He took his family with him, the no-travel laws for Jews briefly waived on the understanding that the award would bring glory on Italy.

In Stockholm, Fermi accepted his award, then used his prize money to get himself, his wife, and his children on a boat to the USA.

And that’s how Italy’s greatest modern scientist came to leave his country behind for good. It’s curious to think that, had Mussolini not suddenly passed those anti-Jewish laws, Fermi would’ve likely stayed in Italy for the duration of the war.

All the work he’d do under Oppenheimer would be lost. Lost, too, would be the world’s first nuclear reactor, soon to be built under Fermi’s watch in Chicago. And Fermi was just one of thousands of scientists who fled the continent in those days.

Had Europe’s fascists not become so obsessed with national purity, their nations would ironically have lasted so much longer.

On January 2, 1939, the Fermis arrived in New York City.

For the rest of their lives, the Fermis would call America “home”.

“A labor of considerable scientific interest”

Barely had Fermi set foot inside Columbia than he was already gifting his new government breakthroughs. That same spring, 1939, the Italian and his team showed that emitting neutrons into uranium that was in the process of fissioning could trigger a chain reaction.

In other words: KA-BOOM.

By March, the university was already writing to the Navy, suggesting that this could be used as a weapon. Nor was Fermi himself blind to this possibility.

One day in a Manhattan highrise, he glanced out a window at the bustling city and murmured “a little bomb like that and it would all disappear.”

But Fermi was no Oppenheimer, tortured inside by the destruction his research could wreak.

He actually went to Washington, DC personally to try and drum up funding for nuclear weapons research. But his presentation was so singularly uncharismatic that he walked away with only the smallest of grants. It wasn’t until Albert Einstein personally wrote to Franklin D Roosevelt about the potential for superweapons that the American government began to really show interest.

Still, it was a slow process. Only on December 6, 1941 was a project to study these theories in Chicago signed off on.

But if things had been moving slowly for Fermi’s research up until that point, they were about to gain a sense of extreme urgency.

So, you remember history class. You know what happened on December 7, 1941.

The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor dragged America kicking and screaming into the war. It also had the side effect that every Italian in the country was immediately classed an “enemy alien,” and subjected to severe travel restrictions.

It took nearly six months for Fermi’s restrictions to be waived for his research. He finally arrived in Chicago in summer, 1942.

But once he was there, Fermi almost immediately proved his worth. We already spoke one terrifying parallel universe earlier, where the Axis got the Bomb. Now we’re going to speak about a much weirder one. The universe where this video isn’t titled “Enrico Fermi: Godfather of the Atomic Bomb”, but “Enrico Fermi: the Mad Scientist who Destroyed Chicago.”

Fermi and his team assembled a nuclear reactor on the squash court of the University of Chicago toward the end of 1942.

On December 2, they sent it critical. As the New York Times later wrote of the potentially-dangerous experiment:

“The only safeguards against an uncontrolled atomic chain reaction that would have irradiated a significant part of Chicago was a scientist wielding an ax to cut the rope that held an emergency control rod suspended from the balcony, and a few other brave volunteers, whose job was to douse the runaway reactor with buckets of neutron-absorbing cadmium sulfate.”

Fermi actually joked that, if the reactor went out of control, the assembled team should run and hide behind a big hill many miles away.

But, of course, Chicago Pile-1 didn’t become Chernobyl before Chernobyl. It worked, creating a self-sustaining atomic chain reaction – the first working nuclear reactor in history.

Shortly after, a code was broadcast to Washington, DC: “The Italian navigator has just landed in the new world”.

It was the dawn of the atomic age.

It was also the dawn of a new age in Fermi’s work. In 1944, the Italian physicist became a naturalized US citizen. Shortly after, he was sent down to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project under Robert Oppenheimer.

Fermi was actually there on July 16, 1945, when the first Plutonium bomb was tested, at the infamous Trinity test in Alamogordo, New Mexico. This was the moment when Oppenheimer, seeing the power he had unleashed, thought the phrase “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

But – as we’ve said before – Fermi was no Oppenhemier.

Faced with the reality of a weapon capable of wiping out entire cities in the blink of an eye, Fermi only noted that the Trinity test was “a labor of considerable scientific interest.”

How I Learned to Stop Worrying…

In the last months of the Manhattan Project, Fermi’s dedication to building the Bomb didn’t waver. Although in April, he noted that their labors would one day be able to be reproduced by “smaller nations or even groups,” he still thought it a worthwhile endeavour.

That June, he joined the Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee, a group tasked – in part – with advising on the use of atomic weapons against Japan.

Just like his colleagues, Fermi advocated for an atomic strike. Although some members of the panel did object on ethical grounds, preferring instead a public test that would give Japan warning, President Harry Truman signed off on an attack.

Just two months later, on August 6, 1945, a bomb distilled from the work of Fermi, Oppenheimer, and the other geniuses at Los Alamos was loaded onto the Enola Gay and flown off into the night sky.

Six hours later, the Enola Gay’s bomb bay doors opened above the commercial and military city of Hiroshima. Little Boy dropped for 44 seconds.

At the end of that time, the world changed forever.

The first atomic bomb ever used in warfare detonated at precisely 08:16:02 am some 609 meters above Hiroshima. Within 0.1 of a second, the air over the city center had reached 277,760 C. A woman sat nearly a kilometer away on the banks of the city’s river was instantly vaporized.

As the fireball expanded, granite stones melted, the internal organs of humans and animals vaporized, and exposed skin was burned off.

By the time a single second had passed, a blast wave traveling at 1,500 km/h had torn the clothes off nearly everyone in the city, destroyed 60,000 buildings; and an intense firestorm had started that would rage for hours and hours.

In that instant, 80,000 people died, including up to 20,000 Korean slave laborers and over a dozen Allied POWs. Many tens of thousands more would die of radiation poisoning over the coming weeks.

It was carnage on a previously unimaginable scale. And it wasn’t over. Three days later, on August 9, another plane carrying another bomb flew over Japan. Originally, it was meant to drop its payload on the ancient city of Kokura, but thick cloud cover meant that Nagasaki became its target.

At 11:02am, Fat Man exploded above the port city, turning over 40,000 people into ash. It was the second, and – to date – last time atomic weapons were used in warfare.

Six days later, Japan surrendered unconditionally.

Today, it remains up for debate whether the real motivation for Japanese surrender was the two atomic bombs, or the USSR’s declaration of war the same day as Nagasaki. Whatever the truth, there’s no denying that the weapons Fermi helped build had just shocked the world.

By now, though, the war was already over in Europe.

In Italy, partisans had captured Mussolini back in April, stringing up his corpse in a Milan square. Hitler, too, was dead – killed by a self-inflicted gunshot in his Fhurerbunker. The fascists who’d chased Fermi and his family out of Europe were gone. The physicist could now go back to his home country whenever he chose.

But what remained in Italy for him? His wife’s family were dead, killed in the Holocaust. Rome lay in ruins.

Instead, in fall of 1945, Fermi accepted a teaching position at the University of Chicago. He would live in the city for the rest of his life.

The Last Paradox

The last years of Enrico Fermi’s life were marked by a return to the magpie-like fascination that characterized his earlier years. At Chicago, he moved on from nuclear physics and began researching elementary particles, before becoming obsessed with cosmic rays.

Perhaps his most-famous contribution to science in this time, though, came not in the form of a discovery, but of a question.

“Where is everybody?”

In 1950, Fermi was lunching with some colleagues when they began to discuss alien civilizations. This was three years after the supposed Roswell Crash, a time when UFOs were all the rage. One by one, Fermi’s friends asserted that there were undoubtedly aliens out there in the galaxy.

It was at this point that Fermi asked his question.

“Where is everybody?” may sound like a flip remark, but Fermi had a serious point.

He’d realized that – given the immense age of the galaxy – any civilization with even the most rudimentary rocket technology should’ve colonized it by now. Assuming even a hyper-conservative estimate for how often an intelligent civilization arises, the sheer time scales involved meant there should be abundant evidence of aliens by now.

So, again. Where is everyone?

Today, that simple question is known as the Fermi Paradox, and the list of explanations as to why there are no signs of alien life could fill a dozen videos all by themselves.

Seriously, if you want to head down an infinite click-hole, just type “the great filter” or “dark forest theory” into Google.

But while Fermi may have meddled in many disciplines in his later years, he could never quite escape the one thread running throughout his working life: nuclear physics. In 1949, Fermi joined the General Advisory Committee to the Atomic Energy Commission.

That year, the USSR had tested its first atomic weapon, and the Committee had gathered to decide on the practical and moral implications of the USA developing thermonuclear devices.

Unlike the atomic bombing of Japan, Fermi was steadfastly against the idea.

A hydrogen bomb, he wrote in an dissension from the majority opinion, “becomes a weapon which in practical effect is almost one of genocide…. It is necessarily an evil thing considered in any light.”

After a lifetime with no political opinions at all, it seemed Enrico Fermi was finally waking up to a world where governments might use his discoveries for evil.

But this new mindset only went so far. When Truman signed off on the H-Bomb, Fermi dutifully went back to Los Alamos to work on it. It’s said he hoped to prove such a weapon was impossible. If that’s the case, he was doomed to disappointment.

The world’s first hydrogen bomb was tested in the Marshall Islands on November 1, 1952.

The explosion was so vast, so world-changing in its implications, that it graced the cover of Time. Not long after, Fermi came up with his own, pessimistic answer for the Fermi Paradox.

There were no alien civilizations because they’d all wiped themselves out with thermonuclear weapons.

Still, Fermi being Fermi, he carried on working. There were doubtless more discoveries to be made. In the summer of 1954, he even went back to Italy, hiking in the mountains and enjoying the air of the old country.

At least, that was the plan.

The reality was Fermi found himself feeling constantly run down. When he returned to Chicago at the end of his vacation, he went straight to the doctor. Since you can already see we’re nearing the end of the video, you can probably guess what came next.

The doctors told Fermi he had stomach cancer. Although they tried to cure it, the disease was already too far advanced.

Enrico Fermi died on November 28, 1954. He was 53.

Today, Fermi’s name lives on – most notably in the Paradox named after him, and the element fermium, discovered in 1953. While it’s doubtful the average Joe has heard of him, he remains highly-respected, a genius who still gets his due.

Yet its interesting to recall just how unlikely this great reputation was.

If things had been just a shade different, Fermi could’ve gone down in history as the man who accidentally gave the Axis the Bomb. Or he could’ve become trapped in Italy in 1938, and perished alongside his wife in the Holocaust.

He may even have made it to America, only to send Chicago Pile-1 out of control and cause the world’s first nuclear meltdown. Thankfully, this universe is one where disaster never struck; where Fermi’s genius helped shape the world rather than end it.

He may have lived a relatively short life, but Fermi did enough work in his five decades to fill hundreds of lifetimes.

Sources:

Biography’s take: https://www.biography.com/scientist/enrico-fermi

Britannica’s take: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Enrico-Fermi

Interesting overview of his life and contributions to science, including testing the first nuclear reactor: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/20/books/review/enrico-fermi-biography-pope-of-physics.html

In-depth, math-focused bio: http://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Fermi.html

The Fermi paradox: https://www.seti.org/seti-institute/project/fermi-paradox

Mussolini’s rise to power: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Benito-Mussolini/Rise-to-power

https://www.biography.com/dictator/benito-mussolini

Mussolini’s death: https://www.history.com/news/mussolinis-final-hours-70-years-ago

Timeline of the Hiroshima bombing: https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/hiroshima-and-nagasaki-bombing-timeline