For as long as mankind has had currency, a system of trading, and a market economy, the world has been split into the “haves” and the “have-nots,” … and for much of that time, there’s been a huge gap between the two. The idea of the 1 percent isn’t a new concept by any means, and in order to talk about one of the richest men in history, we’ll have to go all the way back to the 15th century.

The man who would become known as Jakob Fugger the Rich was born in 1459, and he had an advantage that few people get, then or now — he was born into a well-to-do family. But through a series of investments made with incredible foresight and a willingness to risk it all, Fugger guided his family to become one of the richest and most influential in history.

Here’s how he did it.

Just How Rich is Rich?

Since we’re going to be talking about Jakob Fugger in the context of his wealth, it’s worth investigating just how rich he really was. Perspective is key, after all, so let’s compare his fortune to that of people who might be a little more familiar.

Take Bill Gates. His highest net worth hit a seriously impressive $144 billion, although he gives so much money away through his foundation, that’s not really an accurate picture. Go back in time about 200 years, and we have John Jacob Astor. He has the honor of being America’s first multi-millionaire; he controlled much of the fur trade in the early 19th century, and when he died, he was worth what would be around $168 billion in today’s money.

Henry Ford tips the scales at around $200 billion in today’s money, which puts him right alongside names like Cornelius Vanderbilt and Muammar Gaddafi. Rockefeller and Carnegie come in somewhere in the middle of the $300-billion range.

Fugger was richer than all of them.

There’s a few different ways you can look at wealth, and given the fast-changing modern economy, plus factoring in inflation, a simple numerical comparison doesn’t really carry much weight. It’s estimated that in today’s US currency, Fugger would have a net worth of somewhere around $400 billion, but there’s so much more to it than that.

Consider Fugger in a grander context. If you took Europe’s entire economic output at the time, he owned 2.2 percent of that. If that doesn’t sound like much, remember: we’re talking about representing more than two percent of an entire continent. For reference, examine John D. Rockefeller’s value — when he died in 1937, he owned only 1.5 percent of America’s gross domestic product. And that’s just one country.

But before you get bogged down by dollar signs, don’t forget — we aren’t just talking about the value of money. Fugger wielded a great deal of power and influence, and that can be the most valuable currency of all.

The benefits of a privileged upbringing

Jakob the Rich may have been the economic savant who catapulted the family fortune to newfound heights, but the Fugger fortune wasn’t built on the shoulders of one man. There are a few others in the family that deserve an honorable mention.

Jakob’s grandfather, Hans, was born into a peasant family in southern Germany. By 1367, he had moved to Augsburg and made a few wise choices in the game of love. He married twice, and both of his wives were the daughters of masters in the weaver’s guild. That’s not to say he was a master weaver himself, though; Hans didn’t weave at all. What he did do was act as the middleman, providing raw materials for those who performed the manual labor. Later, he would buy the finished textiles and sell them at a massive profit.

From there, he moved up in the guild himself, earning a spot on the committee, and eventually serving on the Great Council of Augsburg. Hans died in 1408, but he didn’t pass the business on to his sons; instead, his wife Elizabeth took the reins, and spent the next 28 years using her own business savvy to continue growing the family’s wealth.

Hans had two sons of note, Andreas and Jakob I, and eventually, they made their own fortunes and contributed to the family’s. Both were goldsmiths, and they worked together until disagreements led to a split in 1454. Even though Andreas had more immediate success, that branch of the family was bankrupt by 1499.

Jakob, on the other hand, increased his wealth and standing slowly but surely. He married the daughter of a mint master, and they raised seven sons — all while he grew his status as a member of the city’s merchants’ guild.

Two of his sons were groomed to take over the financial side of the business. The youngest — Jakob II, our future Jakob the Rich — was, like many youngest sons were, on his way to being educated for a place in the clergy.

Jakob — also known as Jakob the Elder — died in 1469. For the next 28 years, once again, the business affairs weren’t in the hands of any of those sons, but were managed by the deceased’s wife, Barbara Basinger. She spent nearly three decades buying and selling, and when it came time to hand control over to the next generation, the family was already quite wealthy.

It was Barbara who sent her youngest son off not just to ecclesiastical studies, but to learn banking and bookkeeping as well. Jakob II was just a teenager when he was sent to Venice to learn the ins and outs of commerce in a major European city; by the time he came back, he had learned skills that would serve him well. He studied not just the principles of trading and commerce, but he also learned how to read, write, and speak multiple languages. He also mastered more obscure things, like the formulas for making conversions between various weights, measures, and currencies.

And then, there was accounting. The idea is common enough today, but at the time, German merchants still relied heavily on a haphazard system of receipts. Organization was rarely included as a part of a German merchant’s job description, but things were quite different in Italy. There, they had developed extensive systems of bookkeeping, an accounting procedure that made it possible to stay on top of multinational companies and trade that spanned the length of the Silk Road.

Jakob was going to need to know how to do all of it.

A First Taste of Wealth and Power

It was several years before Jakob returned to Germany, and by that time, his older brother had already set up a firm of their own. It was called Ulrich Fugger & Bros., and Jakob started out with a 29 percent ownership stake. He wasn’t working with them for long when he witnessed a deal that made a lasting impact on him — and taught him a very important lesson about the makings of a king.

Ulrich Fugger was approached by the Habsburg Emperor Frederick III. He was installed as Holy Roman emperor in 1452, and his reign was both turbulent and historically significant. He dealt with a series of revolts and revolutions, as well as continued unrest on the eastern border of his kingdom. He was on the front lines of the long-running battle between the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe, maintaining a firm relationship with the church, but struggling to consolidate his territory into a unified power.

One of the most important things he’s still known for isn’t necessarily what he did, but what he laid the groundwork for. In 1477, he made a deal to join his family with the Duke of Burgundy’s via the marriage of his son to the daughter of Charles the Bold. Before the marriage could be agreed upon, though, Frederick needed to impress the Burgundians to prove his family’s worthiness. With the coffers running dry, he turned to the Fuggers.

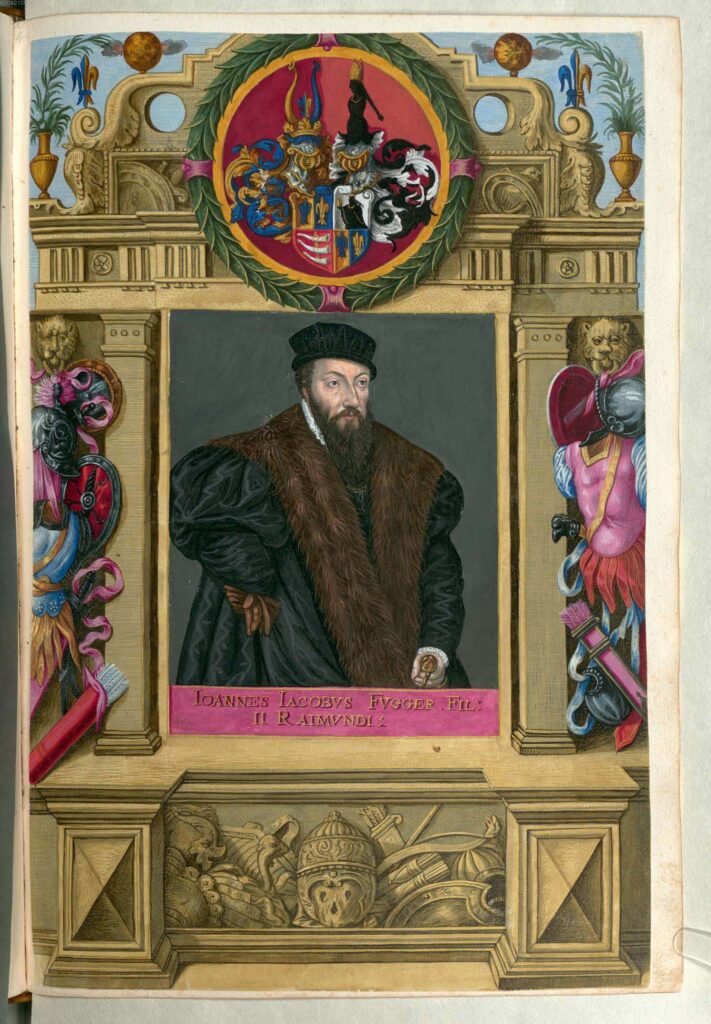

Frederick III found himself in dire need of fine textiles, and that was precisely what the Fugger family did best. Jakob watched as his older brother made the deal: he would give the Holy Roman Emperor the fine silks and wool he needed to impress Charles, but he wanted something in return. That was a coat of arms, bestowed upon all the Fugger brothers. It doesn’t sound like much, but for the family, it was a huge deal that allowed them to rise from just being well-to-do members of the merchant class to being a bona fide family of standing and clout.

It was a win-win — the deal also helped Frederick to close on the marriage proposal, which, in turn, consolidated power and made Austria a force to be reckoned with.

From all of this, Jakob learned that even kings would bend the knee before money. Every haggle might come with some natural give and take, but a careful negotiation could have a very far-reaching outcome, indeed.

In 1485, Jakob made his first solo deal. The 26-year old was still working for his brothers when he headed off to Schwaz, Austria, with a desire to break into the mining industry. His brothers had given him full authority to make any business decisions he deemed appropriate, which turned out to be one of the better decisions that the family made.

Jakob met with Sigismund, the Archduke of Austria and ruler of Tyrol. Prior to his elevation to these particular titles, Sigismund was a ward of his cousin, the aforementioned Emperor Frederick III. When he was given regency over Tyrol and several other territories, he was handed incredibly valuable lands, rich with silver mines. And while Sigismund may have been instrumental in promoting and growing his country’s mining industry, he also liked to spend money as fast as it was mined. His love of extravagance earned him the epithet “Rich in Coin,” but he wasn’t always able to keep up with his spending.

Enter Jakob Fugger. He had the extra cash that Sigismund so desperately needed, so they struck an intriguing deal — Jakob agreed to lend the Archduke a sizeable sum, and in return, the Fuggers would gain the rights to the area’s silver mines. Money upfront in return for the possibility of money in the future seemed like a brilliant trade, so Sigismund took it in exchange for a thousand pounds of silver, delivered over several installments.

He did, in fact, deliver the mined silver as promised, which wasn’t always a guarantee — as an Archduke, could have just leveraged his own power and standing to decide he wasn’t going to bother with repayment. Fortunately for the Fuggers, the deliveries came in right on time, and Jakob was able to sell that same silver in Venice at a 50 percent markup. And that’s what we call good business.

The Fugger fortune didn’t come from that thousand pounds of silver, but that first deal did something else — it cemented a relationship between the Habsburg dynasty and the Fugger banking empire, because just four years later, Sigismund found himself in dire need of more help.

This time, his troubles started with the outbreak of a border dispute between Innsbruck and Venice. Frankly, calling it a “border dispute” is putting it rather mildly. After noticing that the Venician military occupied in a fight with Turkish forces in Greece, Sigismund launched a modest opportunistic attack, claiming a small Alpine town and extending the Austrian borders. It probably goes without saying that Venice wasn’t terribly happy about this. They issued their response in no uncertain terms: Sigismund could either return the town and pay 100,000 florins in restitution for his brovado, or he could prepare for Venice to take back their town by force.

Sigismund appealed to the family’s regular financiers, but no one was willing to lend him the money. They refused not because of his military action, but because he had already managed to run up massive debts that he hadn’t yet repaid. Desperate, he returned to Jakob Fugger.

Where other bankers saw a risk, Jakob saw an opportunity. He agreed to lend Sigismund the money he needed, but the interest on the deal was going to be massive. The contract stated that the loan was going to be repaid with more silver from Sigismund’s mines — all output was to be sold to the Fuggers at an almost unthinkable discount, until the loan was repaid. The Fuggers could then turn around and sell that silver, and they stood to make what could safely be described as boatloads of cash.

The deal wasn’t without risks. Sigismund had already proven he couldn’t repay his regular bankers, and there was the very real possibility he would simply stop sending silver to the Fuggers. But Jakob had banked on the fact that this was a bridge Sigismund didn’t want to burn, gambling that he would uphold his end of the deal in order to preserve the possibility of future partnerships. It was a little bit about honor, and a lot about knowing he would need to borrow money again in the future, and it all came up shiny for Jakob.

So shiny, in fact, that the Fuggers opened their first branch office in Tyrol, and it’s important to stress that this was a gamble on more than just Sigismund’s ability or desire to uphold his end of the bargain. Metallurgy had been a work in progress for thousands of years; the evolution of the ages of man are defined by advancements in the use of materials like bronze and iron, after all. At the time, Jakob was making deals for silver, but the corresponding smelting technologies had stalled. Starting around 1480, though, metallurgical advancements began happening in leaps and bounds. It was becoming much more economical to separate silver from other metals. In turn, the demand for not silver, lead, mercury, and copper exploded. Portugal, in particular, was buying huge amounts of copper for their ships and their weapons, and the Fugger were well-positioned to capitalize on all of it.

In 1494, Jakob formed the family’s first public company, a mining consortium. His goal was a copper monopoly; to get there, he started investing heavily in copper mining, buying everything from mines to smelting plants across present-day Slovakia.

It’s impossible to tell just how massive this portion of their industry was, as they were incredibly secretive when it came to the technology they used and the numbers they saw floating across their accounts. We do know that it wasn’t long before they had built up a massive trading empire that stretched from England to India and Africa.

It was an industry that sustained the family wealth well into the 16th century.

Bankers to the rich, the noble, and the elite

In 1491, Jakob had made another wise decision — he organized a loan to Maxmilian I, the son of Frederick III. When Maximilian became a ruler in his own right after his father’s death in 1493, that cemented Jakob’s continued standing as a banker to the powerful and not-so-rich men of the 15th and 16th centuries. That — alongside the aforementioned investments into a burgeoning mining industry — meant that the Fugger family coffers were filling fast. Still, Jakob was always on the lookout for the next big deal.

The trades came in faster and faster. By 1503, they had gotten into the lucrative spice trade. Only five years later, they were leasing mints in Rome, and among the coins they were in charge of minting were those for the Vatican. They kept that particular little side business until 1524, and here’s where it’s worth mentioning one endeavor in particular.

In 1514, one of the most powerful positions in the church and in the political world became available. It was for the archbishop of Mainz, a high-ranking position in Germany second only to the emperor himself. The pope at the time was Leo X, and while that name might not sound particularly familiar, his birth name will: Giovanni de Medici.

His reign as pope is still known as one of the most extravagant — he was known as a patron of the arts, and that’s putting it politely. Elected to the papacy in 1513 at 37 years of age, he made it his mission to elevate the Vatican into something divine. In order to collect the enormous sum of money he needed to renovate the holy city, he started doing some shady things that most devout Catholics absolutely didn’t agree with, like selling holy positions within the church.

The position of the archbishop of Mainz was one that was up for sale, and anyone who wanted to buy their way into the seat was going to have to pay up. How much? Adjusted for inflation, it would cost the equivalent of about $4.8 million in today’s money. It was Albrecht of Hohenzollern who was determined to have it, and he turned to Jakob Fugger for financing.

Jakob agreed, and he deposited the money right into the pope’s personal bank account. Hey, you’ve at least got to admire the openness of it all, right? Albrecht got the position, but now he had a hefty loan he needed to repay.

And how on earth was he going to do that? Like most of Jakob’s deals, it was complicated — and there were a few players in place. With the support of the pope, Albrecht started selling indulgences, or get-out-of-jail free cards for Heaven. The idea was that anyone who was willing to make a sizeable “donation” to the church would have their sins immediately erased, and their way into Heaven paved… presumably, with the silver and copper from Jakob’s mines.

Perhaps to make the tale even more believable, the church arranged for the sale of indulgences while claiming all the money was paying for some much-needed work on St. Peter’s Basilica. In reality, half of the money went to the pope, and the rest went to Jakob.

There were some major consequences, though: the sale of indulgences was so unthinkable to some Catholics that they decided it was worth breaking from the church over. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were kick-started by outrage over the selling of indulgences, eventually leading to the Protestant Reformation.

That sequence of events is pretty much a perfect example of Jakob Fugger’s influence: he may not be a name that everyone recognizes in the 21st century, but thanks to his financial support of powerful Kings and Clergymen across Europe, he completely rewrote world history.

A Florin Goes a Long Way

Jakob Fugger’s wheelings and dealings are too many to list, so perhaps a better way to talk about the lasting impact he had on the world isn’t just to talk about how he made his money, but how he spent it.

Let’s take the Fuggerei; in 1517, Jakob oversaw the groundbreaking of what would be a global first. After years spent amassing a fortune larger than a single person could spend in a lifetime, Jakob wanted to give back to the community. To that end, he built a housing complex called the Fuggerei. It’s located in Augsburg, Germany, and it’s entirely accurate to describe it as a city within a city. Opened in 1520, it was designed to provide housing to low-income tenants; it includes 147 apartments, 67 houses, and a church. Those who live there had to apply and meet specific criteria: they had to prove their devotion to the Roman Catholic faith, have no outstanding debt, be struggling to make ends meet, and have lived in Bavaria for two years.

What are the bonuses? Rent was just 88 cents a year, and three prayers a day.

That’s impressive, but what’s more impressive is that 500 years later, the Fuggerei still welcomes tenants who are in need, and the rent has remained absolutely unchanged.

The effect that Jakob Fugger — and, indeed, the Fugger family — had on the world is impossible to trace, and there’s some things that we only have time to mention in tidbit form. After Maxmilian’s death in 1519, Jakob’s support of Spain’s Charles I led to the Habsburg ruler becoming the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Jakob also loaned a large sum of money to Ferdinand Magellan, who took that money and set off on his famous expedition to circumnavigate the globe. He even set up a news service, in which he was sent letters from around the world, updating him on the economic and political situation in all his areas of interest — essentially, it was a newspaper before newspapers were a thing.

The end of the Fugger family came gradually. In 1512, Jakob brought four of his nephews on board; with no children of his own, he knew he needed someone to pass the business on to. It wasn’t until 1525 that Jakob the Rich willed everything to his nephew Anton, with the stipulation that a brother and a cousin would be kept on to advise him. Jakob died that same year, while unrest swept across Hungary.

Still, the business continued to grow, and the firm reached its peak in 1546. They continued to establish charitable organizations (like a foundation for the treatment of smallpox), but the very thing that had allowed Jakob to become one of the richest men in the world was the same thing that led to the family’s downfall. They were so closely tied to the Habsburgs and the fortunes of Hungary that, as trade worsened, so did the family’s financial opportunities. By 1550 — two years after their withdrawal from the Hungarian trade market — Anton Fugger told his sons to focus on their education and find their own fortunes in the courts of Europe. Their Spanish branch was bankrupt by 1557, and after Anton’s death in 1560, other branches that had become unprofitable were sold. Leases on mines were returned, the family withdrew from Spain, and in 1658, the firm was dissolved completely.

It may have been the end of a dynasty, but the Fugger family influence has lasted much longer than their fortune.