Without a doubt, one of the most exciting periods in history was the Industrial Revolution. At perhaps no other time was there a greater feeling that the sky was the limit. Innovations happened one after another and they all seemed destined to change the world forever.

Assuredly, one of the most important novelties of the 19th century was the railway. It marked a decisive shift in how people could travel the world. Distances that previously seemed unreachable were now just a day or two away. And we might have never enjoyed this revolution without George Stephenson, a man aptly named the “Father of the Railways.”

Stephenson was completely self-made. Here was a man born into a family of illiterates, a man who couldn’t read himself until he was 18 and who had to get his first job at the age of eight to help support his family. And yet, he became one of the most successful and most innovative engineers in British history and today we are looking at his incredible story.

Early Years

George Stephenson was born on June 9, 1781, in Wylam, Northumberland, an English village situated on the banks of the River Tyne. He was the second of six children to Robert and Mabel Stephenson and they all lived together in just one room of a house that contained three other families.

Wylam was a coal town, located just a few miles from Newcastle. Most blue-collar laborers worked at the nearby colliery, as did George’s father Robert, or “Old Bob” as he was known in town.

The Stephensons were well-liked in the village. Mabel, the daughter of a dyer from Ovingham, was described as being a woman with a delicate constitution but, overall, a “real canny body.” Old Bob was popular with the local children who used to gather by the engine fire as he was tending it and listen to Bob tell stories. They were nice people, but completely uneducated. Both parents were illiterate and so were the children because the family was too poor to afford education for any of them.

Unsurprisingly, under these conditions, it was expected that the boys would eventually join their father to work in the coalmine. George was eager to help out the family and he got his first paying job when he was just eight years old. By then, the Stephensons had moved to Dewley Burn and Old Bob worked at the colliery they had there. Young George, or Geordie, as he was called, found employment with his neighbor, a widow who paid him twopence a day to keep an eye on her cows while they grazed and make sure that they didn’t stray into the neighboring lands. It was easy work that afforded the boy lots of free time which he dedicated to two of his favorite pursuits: watching birds and making engines out of clay.

As he grew up, George took on more jobs on the farm until he was old enough to start working in the coalmine alongside his father and elder brother James.

By necessity, the Stephensons moved around a bit whenever a mine started to dry up and another one was opened someplace else. However, George never found it difficult to secure a new job as he was hard-working, conscientious, and strong. By the time he was a teenager, he fulfilled his ambition of becoming an engine-man. It was clear that George developed a fascination with engines ever since he was a child. Now that he had his desired position, he worked with engines every day and took the time to clean and study and understand every component.

When he was 18, George Stephenson realized that there was a hard limit on how much he could learn without being able to read so he sought to correct this flaw. He used his meager salary and began attending night school and, by the time he was 19, he knew how to read and could also write his name. Then, he moved on to a better, more expensive teacher who taught him arithmetic and George soon discovered that he had a talent for working with numbers.

This was George’s life for several more years. He moved on from one mine to another, being promoted as he became more experienced. He met a woman named Frances Henderson and the two married in 1802. They had their son, Robert, a year later and, of course, Robert Stephenson would go on to become a great engineer in his own right, perhaps even greater than his father.

Unfortunately, George’s life was soon marked by tragedy. In 1806, Frances died of tuberculosis, or consumption as it was called back then, leaving him heartbroken. Then, George left for Scotland for a while after securing a well-paid position there. He saved up quite a bit of money but, when he returned, he discovered that his father had met a serious accident on the job after being struck with a steam blast to the face. The injury had left Old Bob blind, infirm, and in poverty. George used most of his money to cover his father’s debts and to secure a nice cottage for him to live out his remaining years.

The Miner’s Lamp Controversy

Before he got involved with railways, George Stephenson had another important invention to his credit – the safety lamp. This creation brought him into conflict with esteemed scientist Sir Humphry Davy over who had the better design and who came up with it first.

Back in Stephenson’s time, working in a coal mine was very dangerous. It still is, to be fair, but back then explosions were a regular problem, caused by buildups of various flammable gasses collectively referred to as firedamp. There was a big one in 1806, at the pit in West Moor where Stephenson worked as a brakesman, which killed ten people and George witnessed it firsthand.

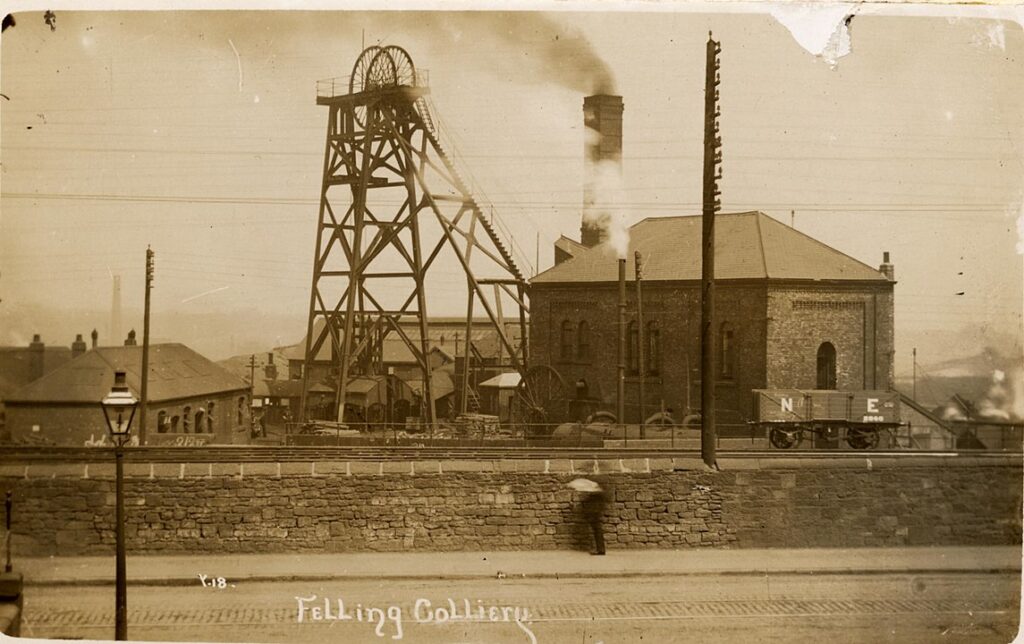

By far, the most destructive disaster occurred at Felling Pit on May 25, 1812. Ninety-two men and boys as young as eight years old were killed in the blast, but this finally prompted demands that mining safety standards needed to change.

What miners needed was a safety lamp. One that would provide adequate light without having a naked flame that could trigger explosions. Ideally, it would also alert the miners if they were in a dangerous situation with a lot of gas building up around them. In 1815, they got not one, but two such devices to choose from – there was the Davy lamp and Stephenson’s Geordie lamp.

By that point, Humphry Davy had already been knighted and was considered one of the preeminent scientists in England. His safety lamp received a lot of attention and was quickly adopted throughout most of the country. That was except for the Northeast of England where the Geordie Lamp was far more popular, perhaps out of a sense of camaraderie as it was designed by one of their own.

Each lamp had its set of benefits and drawbacks. The Davy lamp encased the flame in a screen made out of iron gauze while Stephenson used paper. Therefore, the Geordie lamp emitted a brighter light, but was more fragile. A more important distinction was that Stephenson’s lamp had a separate inlet and exhaust. The opening of the inlet could be adjusted so that only enough air needed to light the lamp would pass through. If the amount of firedamp began increasing to unsafe levels, then not enough air would enter the lamp and the flame would simply extinguish. This would not only prevent an explosion, but also alert the miners that they were in a dangerous situation. However, a strong current could force a lot of air inside the lamp and greatly enlarge the flame, making the lamp too hot to handle.

The world at large preferred the Davy lamp, not necessarily because it was better, but because of who invented it. In fact, Davy and his supporters all accused Stephenson of stealing his design. Curiously, Davy himself faced the same accusation from an Irish inventor named William Reid Clanny who built his version of a safety lamp in 1813, two years before both other men.

The Clanny lamp, however, used a bellows and a pair of water tanks to keep an isolated flame burning inside a metal case with a glass window. It was heavy, unwieldy, dim, and required a man to operate it continuously so it was never used much in practice. Moreover, it was distinct enough from the other two lamps that nobody truly considered that Davy or Stephenson “borrowed” any design ideas from it.

The world remembers Humphry Davy as the inventor of the safety lamp. Indeed, the Royal Society awarded him the Rumford Medal for his efforts in 1816, as well as £1,000 prize money. This was in addition to another £2,000 which Davy received from the colliery owners of England. Meanwhile, the same colliery owners only gave Stephenson 100 guineas.

It was pretty clear that the scientific community of England sided with Davy. Many of them simply refused to believe that an uneducated, working-class man like Stephenson could invent such a device by using only intuition, common sense, and trial and error.

And yet, that is exactly what happened. Unhappy with the way their self-made engineer was treated down south, a northern committee was formed in Newcastle to help determine priority for the safety lamp in favor of Stephenson. They established a timeline. Davy presented his lamp to the Royal Society on November 9, 1815. His earliest communication regarding the lamp was in a letter to a friend, dated October 30. And yet on October 21, Stephenson had already begun using a modified oil lamp for early trials. Based on the evidence, the Newcastle committee raised another £1,000 and awarded it to George Stephenson for his Geordie lamp.

The most probable story is that neither man stole anything from the other, they just had similar ideas around the same time. Even so, this experience bred a lifelong distrust of London intellectuals for Stephenson. He made sure to educate his son Robert in a private school so that he would get rid of the thick northern accent that his father had which he believed negatively influenced other people’s impression of him.

The Engines

Around the same time that Stephenson began working on the safety lamp, he also designed and built his first steam locomotive while working at the Killingworth Colliery. As engine-wright, he already employed the use of stationary engines to improve the transport of coal, but he became convinced that a locomotive, or “travelling engine” as he called it back then, would be even more efficient.

He had plenty of inspiration. Because George Stephenson is nicknamed the “father of the railways”, some people incorrectly assume that he built the very first steam locomotive, but this is not the case. That honor is usually ascribed to British mining engineer Richard Trevithick. On February 21, 1804, his machine (which he never bothered to name but became known as the “Pen-y-Darren locomotive”) made the first railway journey, traveling nine miles from the Penydarren Ironworks to the Merthyr-Cardiff Canal in South Wales. The engine never made it back because a bolt sheared and the boiler leaked, but it did haul five wagons carrying 70 men and ten tons of iron, showing mine owners everywhere the potential for locomotives.

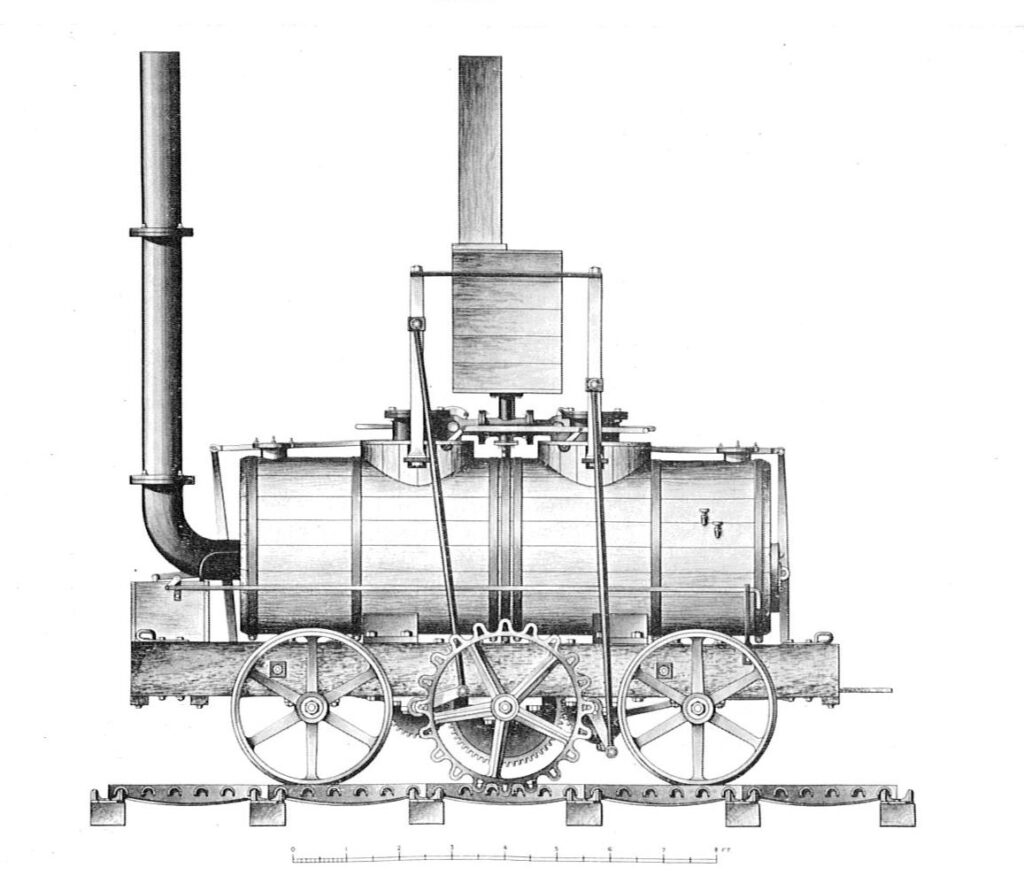

Even so, Trevithick’s machine proved to be too heavy and the rails couldn’t support its weight. It wasn’t until 1812 that John Blenkinsop designed and Matthew Murray built Salamanca, the first practical and commercially successful steam locomotive.

Unsurprisingly, given his passion for engines, as soon as Stephenson heard of it, he wanted to build his own locomotive. He convinced the higher-ups at the Killingworth Colliery to fund his project and, on July 25, 1814, the first Stephenson locomotive made its maiden voyage. He named it Blücher after Prussian General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher who had recently defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig and, a year later, would go on to best him at Waterloo, as well.

The locomotive worked, but it left a lot to be desired. It was clunky, jerky, loud, and, from a financial perspective, was just about as economical as the traditional horse-drawn carriages. Despite the flaws, Stephenson was allowed to keep working on new and improved designs. Unfortunately, Blücher did not survive long as the engineer tore it to pieces and reused the parts to save on costs. In total, it is said that George Stephenson built 16 locomotives at Killingworth, although they are not all well-documented.

The Railways

Following his projects at Killingworth, Stephenson officially established himself as one of the top names in his field. He was next tasked not with designing a new locomotive, but with building a new railway. Sure, the locomotives were the ones that got all the attention, but the truth of the matter was that railways needed to be modernized, as well. The old ones were generally made out of wood and they were simply not sturdy enough to handle the weight that could be transported by steam engines.

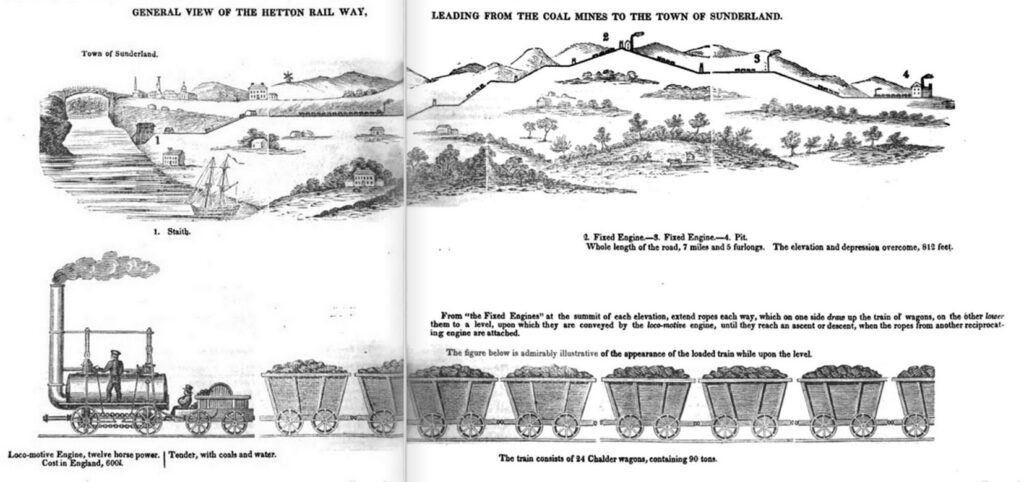

In 1819, Stephenson was asked to build an eight-mile railroad for the Hetton colliery near Sunderland. By this point, his son Robert had joined the family business and helped his father with his building projects. Like George, he showed a passion for engineering at a young age and would lend a hand wherever it was needed.

Stephenson used cast iron for the railway instead of wood. It wasn’t an ideal material as it was brittle, but George considered it the best choice available. He would later switch to wrought iron because it was more malleable and, therefore, a better alternative, even though he lost money as it meant not using his own patented design. The Hetton colliery railway was opened in 1822 and it was the first railway to be operated entirely without animal power.

Afterwards, the building projects kept getting bigger and more ambitious for Stephenson. He was next tasked with building a much longer, 25-mile railway that connected coal mines between the cities of Stockton and Darlington in County Durham. Well, to say that he was “tasked” would be a bit disingenuous as Stephenson lobbied hard for the project. Initially, it was intended to use horse-drawn wagons, but the engineer convinced city and mining officials that a steam locomotive would be faster, more efficient, and more practical. In the end, it would become a mixed railway that used both methods of locomotion.

Construction on the Stockton and Darlington Railway began in 1822 and it opened on September 27, 1825. The railway was notable for multiple reasons, chief among them the fact that it became the first public line to carry passengers by steam locomotive. Railway travel had officially arrived. It was delayed and over budget, but still a landmark moment.

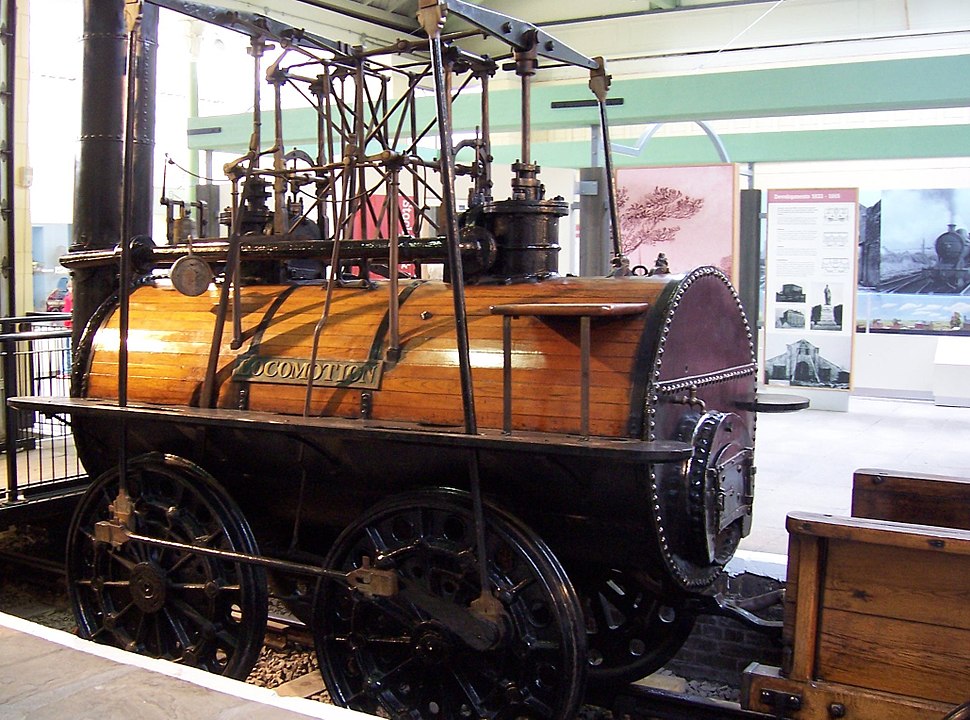

Stephenson was no fool. He realized that railway transportation was only going to get bigger. More lines would be built, perhaps even an entire network all over England. That meant that a lot of locomotives would be needed and someone had to build them, so why not him? With that in mind, the Robert Stephenson and Company locomotive manufacturing business was founded in 1823.

The first engine the company built was also the first to travel on the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Originally named Active, by the time it was finished, it had been rechristened Locomotion No. 1. It was used in the maiden voyage of the railway, reaching speeds of up to 15 mph. Besides wagons full of coal, it also had a coach named Experiment which had been especially designed to carry passengers. Of course, this coach could only seat so many people, but many others were perfectly content riding in the cargo wagons just to be part of this historic journey.

It should be noted that this first trip that transported both people and cargo was intended as a one-off. Afterwards, Locomotion No. 1 and the engines that followed it resumed standard duties of transporting only coal. The Experiment was still used for passenger travel, but it was pulled by horses because it would have been too expensive to use a locomotive just for one coach. It would be a few more years until the first, true steam-powered railroad would be open for business.

From Liverpool to Manchester

That railway would come in 1830 when George Stephenson finished his crowning achievement – the first ever inter-city railway, intended for both passenger and cargo transport, powered entirely by steam locomotives. It went from Liverpool to Manchester, stretching over 31 miles and no horse-drawn carriages were allowed on it at any time. The line was responsible for a bunch of other world firsts such as the first railway to use signaling, the first to function as a mail delivery service, and the first to have double tracks along its entire length, meaning that locomotives could travel in both directions unimpeded.

Despite all these accolades, building the railway included one obstacle after another, especially for Stephenson who served as chief engineer.

It all started in 1824 when the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company was actually founded. The men in charge mostly consisted of merchants, politicians, and other officials from these two cities. These were two of the country’s biggest business hubs (particularly textiles at the time), but transport and communication between them was inefficient. There were two options: the canals, which were slow, and the roads, which were dangerous and congested. A railway would have been superior to both of them.

First off, Stephenson needed to find a route that was suitable for his purposes. He soon discovered that many men objected to the idea of a railway passing through their lands, some even going to the extreme lengths of hiring thugs to keep away surveyors.

Stephenson finally finished his survey, but it was rejected by Parliament for being inaccurate. He made another one and it was rejected for the same reason. As it turned out, he made a major miscalculation in his estimates. In order to cross a boggy area named Chat Moss, the railway would cost up to five times as much as he reported. In 1826, George Stephenson was fired as engineer and was replaced by George and John Rennie alongside Charles Vignoles who served as surveyor. Their project got approval from Parliament in 1826.

Fortunately for Stephenson, despite his mistake, the committee behind the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company insisted that he was hired back as engineer for the actual construction. An interesting tidbit for you: this was the first time that Stephenson used a gauge that measured 4 ft 8½ in or 1,435 mm which would then become known as the Stephenson gauge and, later, the standard gauge as it became adopted worldwide.

In railways, the gauge is simply the width between tracks, measured between the inner sides of the rails. Back then, there was no standard and engineers built the tracks at whatever distance they felt was best. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, for example, another one of England’s greatest engineers, favored the 7-ft gauge. Eventually, Parliament stepped in and passed the Gauge Act in 1846, making the Stephenson gauge the standard throughout Great Britain so that locomotives and wagons could be used on more than just the original railway they were built for.

From an engineering perspective, the inter-city railway was a massive undertaking. Stephenson had to design the Wapping Tunnel, the first of its kind to be bored under a big city. Sixty-four bridges and viaducts had to be built for this 30-mile stretch of railway. And yet, despite all this effort, it almost came to be that the line would function without locomotives.

What the committee wanted was a fast way to move cargo and people between Liverpool and Manchester and, for that, they got the railway. What they weren’t sold on was the locomotives. They thought that it would be better to use stationary steam engines, placed at fixed points along the route, which would pull the wagons using cables. Unsurprisingly, Stephenson disagreed and he convinced them to stage a competition to see which method was best. Taking place in October 1829, it became known as the Rainhill Trials.

Truth be told, they probably could have sorted this out quietly one afternoon, but with the opening of the line fast approaching, they thought that a little publicity wouldn’t hurt so they turned the whole thing into a massive event. There was even a £500 prize and anyone was allowed to enter as long as their machine met certain criteria.

Ten engines entered the competition, but only five were ready on the day. They included Cycloped, a locomotive that was still drawn by horses.

The Stephensons designed a new locomotive especially for this competition and named it Rocket. It would have been pretty embarrassing if they ended up not having the best machine for the railway they built, but the father & son team had no cause to worry. Rocket was not only the fastest engine, but the only one that managed to complete the trials. It was decided that Stephenson locomotives would be used for the railway.

The grand opening took place on September 15, 1830. The Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, had his own special carriage, as did many other esteemed guests such as politicians and foreign ambassadors. The festivities were only slightly marred by the fact that the Member of Parliament for Liverpool, William Huskisson, was accidentally run over and killed by one of the trains, thus having the ignoble distinction of becoming the first reported railway casualty.

Later Life

From then on, the Stephenson company always had more work offers than it could handle as the British railway network kept growing. For some of them they only built locomotives. For others they constructed the entire railroad while, for some, they only did the survey. And, of course, on many railways they did all three. Even so, starting with the mid-1830s, Robert Stephenson began taking on the role of chief engineer while his father took a more passive role. After decades of hard labor ever since he was a small child, George Stephenson was content with stepping back a bit and letting his son build on his accomplishments and his reputation.

In later life, Stephenson often served as consultant, not only for his own company, but also for foreign railroad developers, particularly Americans. He gave talks on railways and took on various positions such as being the first President of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London.

In his personal life, Stephenson married two more times, but had no more children. He bought various estates using the large wealth he accumulated, the last of which being Tapton House in Derbyshire.

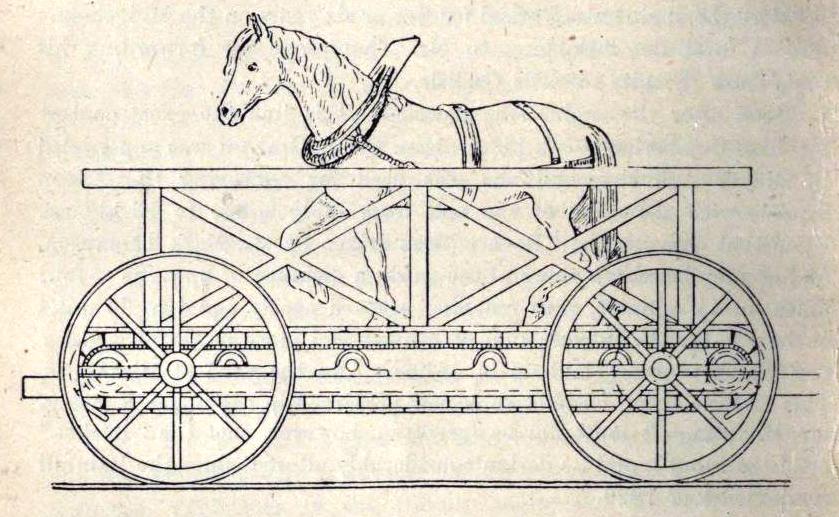

Image: Cucumber straightener

There, he became a very keen gardener and, ever the engineer, gave the world one last invention – the cucumber straightener. Long, straight cucumbers are still popular today and it was during the Victorian Era that this craze first appeared. Stephenson’s invention was simply an elongated glass funnel that would be placed over the vegetable in its early stage to “encourage” it to grow straight.

Just several months into his third marriage, George Stephenson died on August 12, 1848, in his home after a bout of pleurisy. He was 67 years old and the legacy he left behind was evident immediately, but only increased as the decades rolled on and the true significance of the role of the railway network in a new, modern world became undeniable.