Imagine that you’re in charge of sending a culture-bearing probe off into space; one capable of carrying a single example of 20th Century art. What would you pick to represent us in the cosmos? Some great novel, perhaps? Or would you pick a slender volume based on a radio show? A volume emblazoned with the words DON’T PANIC; a volume that contains everything from the precise reason you should always carry a towel, to how to mix the most-powerful drink in the universe?

We’re talking, of course, about the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, perhaps one of the most unique pieces of sci-fi ever written. And the author behind the book we here at Biographics would send as our emissary to the stars? Douglas Adams.

Born in the 1950s, Adams was the product of a post-war Britain exploding with creativity. It was the era of the Beatles and Pink Floyd, of Monty Python, and Doctor Who. Yet even in this intensely vibrant age, Adams still managed to dream up a universe so unique it has arguably never been equalled. In the video today, we’re thumbing a ride into the past to explore the life of the man behind a literary legend.

Mostly Harmless

Far out in the uncharted backwaters of the unfashionable end of the western spiral arm of the Galaxy lies a small unregarded yellow sun. It was on a planet orbiting this unregarded sun, in the year 1952, that Douglas Noel Adams was born.

Later in life, Adams liked to joke that he was the first DNA in Cambridge, having been born there several months before Watson and Crick discovered the far more famous version.

But aside from raising a smile, that gag may have also served to hide painful memories.

The family Douglas Adams was born into was both deeply eccentric, and deeply fractured. A lot of this fracturing came courtesy of the boy’s father, Christopher Douglas Adams.

A bombastic giant of a man with a personality the size of Canada, Christopher was a man who loved booze, cars, and women.

You’ll notice that’s women, plural, not woman, singular, which may be why the Adams household fairly radiated misery.

Before Adams was even five, his parents had divorced, and he’d gone to live with his mother’s parents.

Well, make that “her parents and their animals.” Adams’s maternal grandmother was an animal lover par excellence, and the house was overrun with stray dogs, stray cats, stray badgers, and anything else that might conceivably eat your food and poop everywhere.

Perhaps it was due to the endless clamor in the house, but Adams became so introverted at school that his teachers thought him “mentally subnormal”. But while the boy may have had a weird, unhappy childhood, he never suffered financially.

Not long after ditching his family, Christopher Adams had managed to seduce an incredibly wealthy widow who paid for Adams to have a private education. Thus it was that, aged 11, the boy was dispatched to the elite Brentwood boarding school. For Adams, Brentwood was the first time he ever felt his oddness was appreciated.

Not yet 12, Adams was already a 6ft giant, and would continue to grow until he hit 6ft5.

On top of that, he’d inherited both his father’s gigantic personality and his gigantic nose, making him both a natural performer and instantly recognizable. This translated easily into performing in school plays, where Adams became renowned for his bizarre sense of humor.

Not that it was really his sense of humor.

In 1969, the first season of Monty Python’s Flying Circus had exploded the BBC like a particularly silly stick of dynamite. Like everyone else his age, Adams had fallen in love with the troupe. But while most kids wanted to watch the Pythons, Adams wanted to be them. As he later commented:

“I wanted to be John Cleese. It took me some time to realise that the job was taken.”

But it wasn’t just Monty Python that had gripped Adams’s imagination. Britain in 1969 was in the midst of a full-blown cultural explosion. There was Python’s comedy, the Beatles’ music, Doctor Who’s sci-fi wanderings. With a talent as distinct as Adams’s, it’s tempting to think he just sprang from nowhere. But no, his was a sense of humor born from a particular moment in British history.

But while all the ingredients for his greatest work were in the air in the 1960s, they only coalesced together thanks to pure chance.

In the summer of 1971, Adams was traveling around Europe between finishing at Brentwood and starting at Cambridge University. As the legend goes, he found himself at some point lying dead drunk in a field in Austria, contemplating alternately his Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to Europe and the stars spinning above him.

Just before he lost consciousness, the drunken teenager had a thought that would change his life.

He decided that someone should write a hitchhiker’s guide not to another continent…

…but to the galaxy.

The Python Years

If it was overindulgence in alcohol that gave Adams his great idea, it was likely also alcohol that stopped him from doing anything with it. By 1974, Adams had graduated Cambridge after student years in which he did heroically little work and heroically huge amounts of drinking.

Now he was living in London, still drinking heroic amounts, but doing nothing except writing the odd sketch the BBC would immediately reject.

But while the boozy London life was keeping Adams from his art, it was also gonna give him his bug break.

That same year, Adams was introduced to Graham Chapman.

If that name sounds familiar, it’s because Chapman was the fabled straight man of Monty Python – straight in the comedic sense, as Chapman was openly gay. He was also a man who liked to drink and liked others who liked to drink.

And in Adams, he seemed to have finally found the perfect drinking buddy.

Throughout the year, the two met up to imbibe indescribable quantities of alcohol. The more often they met, the more Chapman became convinced Adams had a talent for sketch comedy.

So he gave him a spot on the biggest sketch show on Earth.

On December 5, 1974, Douglas Adams became one of only two non-members to have ever written for Monty Python. His sketch, Patient Abuse, features Chapman as a doctor who forces a heavily-bleeding Terry Jones to fill out endless inane forms before he’ll give him any treatment.

It’s a classic Adams riff on bureaucracy, albeit one tooled to Python’s specific brand of humor.

It was also successful enough that Chapman asked Adams to keep writing with him after Python ended. In 1975, the two made a pilot for a sketch show called Out of the Trees. We don’t need to go into Trees too much. Only one episode was ever made and, as Adams once said, it “had some good bits, but it wasn’t really that good.”

Still, it’s worth noting the one big sketch Adams contributed.

At the end of the episode, a young couple pick a flower off a bush. This causes a chain reaction of events which begins with the police being called out, progresses to the whole of Europe going to war, and ends with the complete destruction of the world.

From that point on, Armageddon would be a subject that obsessed the young writer.

When Out of the Trees failed, Chapman ditched his new writing partner, drifting back to Python’s surreal embrace. Although Adams would contribute a couple of one-liners to Monty Python and the Holy Grail, that was really it for his sketch writing career.

Depressed, Adams returned to his mum’s house. Over the next year, 1976, he continued to try his hand at writing and performing, but it all went nowhere.

There was the sketch show he went on tour with, which ran at two hours, but only contained one good gag.

There was the pilot series he wrote with a friend, about a pair of astronomers who discover the world is about to be destroyed to make way for an interstellar advertising sign, that the BBC refused to touch. There was even a spec script he sent to the Doctor Who production office, one about the Doctor becoming trapped on a ship crewed entirely by the useless people of society.

But while the Doctor Who team liked the idea, they didn’t pick it up.

Come Christmas, 1976, Adams was trapped at his mum’s place, his career dead in the water, and on the verge of giving up.

At that moment, it must’ve seen to him like 1977 would bring nothing but more disappointment, more bad news. Well, buckle up, because Adams is about to be proven wrong.

The next twelve months were gonna hit the young man like a black ship diving into the heart of a sun.

Hitchhiking the Galaxy

On a dismal February day in 1977, Adams made a trip to London to have lunch with the BBC’s light entertainment producer. It had been over a month since Adams’s depressing Christmas, and paid writing work was still out of reach.

That all changed that fateful day.

As the two ate, the producer happened to mention that he wanted a sci-fi comedy series for Radio 4. He wondered aloud if Adams might like to try his hand at a pilot episode?

And just like that, Adams was a writer again.

Adams’ initial pitch was The Ends of the Earth, a six-part comedy in which every episode would end with the Earth blowing up. But as he was writing the pilot – in which Earth is demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass – Adams decided he needed to give his alien character, Ford Prefect, a job.

At last, that idea he’d had long ago lying drunk in a field in Austria came back to him.

Ford Prefect would be a researcher for the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. From that moment, the concept of Ends of the Earth went out the window, replaced by a series about Ford Prefect, the Guide he was researching, and his human pal Arthur Dent.

By March, the pilot episode for The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was ready to go. The BBC gave it the green light. That June, the cast assembled in London to record the episode. It didn’t take long, and that should’ve been that.

But something had changed in Douglas Adams, a zeal had come over him since he’d decided what his radio show was gonna be about. No longer did Adams simply want to make a radio comedy. He wanted to make something unlike anything anyone had ever heard before. A sci-fi show with production levels Pink Floyd would envy.

For the rest of that summer, Adams and his producer tinkered away in the booth, creating the sci-fi soundscape for their show.

They spent as long on single sound effects as some radio shows did on an entire series.

But it was worth it.

By fall, the pilot was being circulated around the BBC. Everyone loved it. As winter approached, Adams was called in to two very important meetings. The first was with the Doctor Who team, who’d heard his pilot and now wanted him to write a four-part episode.

The second was with Radio 4. They wanted to commission a full series of Hitchhiker’s.

Naturally, Adams said yes to both of them.

This would become a pattern in Adams’s life: taking on so much work he became trapped in permanent panic mode, barely able to finish by the deadline. In the future, this would become a crippling problem that severely limited his output.

But in 1977, Adams was still young, and still just able to get things done. Although it was touch and go.

The biggest problem was that, while Adams had a tone and ideas for Hitchhiker’s, he didn’t have a story. So inventing a plot on the fly became harder and harder. Things got so bad that Adams would be forced to finish episodes inside the booth as the cast were recording around him. When that didn’t work, he had to bring in his friends to finish them for him.

Still, finish them he did.

At 10:30pm on 8 March, 1978, the first episode of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was broadcast on Radio 4. As it went out, Adams presumably clutched his towel and hoped it would be successful.

But even in his wildest fantasies, he couldn’t have forseen how successful it would become.

Doctor Who and the Writer of Death

Adams would later say of Hitchhiker’s sudden success that “It was like being helicoptered to the top of Mount Everest. Or having an orgasm without the foreplay.”

People loved it. Major newspapers raved about it. People flooded the Post Office with letters addressed to the Guide itself. If you’re new to the work of Douglas Adams, you may be wondering what made people so obsessed with Hitchhiker’s.

Here was a show in which the basic plot was that the Earth was destroyed, and now the alien guidebook researcher Ford and his human friend Arthur were stuck traipsing around the galaxy. But the genius of Hitchhiker’s doesn’t lie in the plot, but in the comic concepts the show carelessly threw out by the dozens, each clever enough to make a series in its own right.

There’s the supercomputer Deep Thought, which spends centuries calculating the meaning of “life, the universe, and everything,” only to solemnly report that the answer is 42.

There’s the android Marvin, who is created with a brain so big he can conceive of the futility of his existence and so spends the series in a state of terminal depression. There are time-traveling Chesterfield sofas; a bowl of petunias that’s last thought before plummeting out of space and shattering on a planet is “oh no, not again”; and a spaceship crewed entirely by the most useless members of society.

Yep, that last one is the same idea Adams pitched to Doctor Who. Cannibalizing his own work would soon become a core part of Adams’ method.

By April, 1978, Hitchhiker’s was a British sensation.

A book was swiftly commissioned for Adams to write, along with a second radio series. It was enough work for any aspiring writer. But Adams wasn’t just any aspiring writer. He was a madman with an attraction to impossible workloads.

Which may be why Adams agreed to also take on the job of script editing Doctor Who.

Although it’s overshadowed by Hitchhiker’s, Adams’ year at Doctor Who is semi-legendary. Adams took on the job out of a fondness of the show, and a mistaken belief that it wouldn’t be too demanding. Instead, he found himself working on a show where veteran writers would write a four-page treatment for a four-part serial, hand it to the script editor and tell him to turn it into two hours of television.

This meant Adams doing the work not only of ten people, but also handling rewrites on top of that.

But it also meant a year of Doctor Who filled with Hitchhiker’s-style inspiration.

The highlight of this was City of Death, a four part story set in Paris where the Doctor steals the Mona Lisa, meets Leonardo da Vinci, shares a scene with John Cleese, and accidentally creates all life on Earth. It’s a fun, joyful, hilarious bit of TV, and it was written in a single, panic-and-alcohol fueled weekend when the original writer dropped out at the last second, leaving Adams to pick up the pieces.

Incredible as City of Death was, though, it severely restricted Adams’ time for working on Hitchhiker’s.

By early 1979, Adams was in a catastrophic state of procrastination on the book adaptation, with almost nothing written.

Finally, as the deadline swept by, his editor just told him to finish whatever page he was on and hand the damn thing over. With a third of the original season still unadapted, Adams meekly complied. Book one of the Hitchhiker’s trilogy was published in September, 1979. It immediately shot to the top of the bestseller lists. Aged only 27, Adams was now at the head of a bona fide phenomenon.

Now all he needed to do was make sure it didn’t go to his head.

God and Nature

The 1980s began in a whirlwind of success for Adams.

As the rest of Britain embraced the Thatcher era – reluctantly or otherwise – Hitchhiker’s season two went out on radio, followed by the second book, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, and then a BAFTA-winning BBC TV adaptation.

With all this exposure came what every struggling writer always craves.

Money. Lots and lots of money.

By 1981, Adams was a seriously wealthy guy. He began channeling his father’s spirit, blowing cash on cars, girls, meals, music, and computers. Yes, computers. One of the reasons companies like Google program Hitchhiker’s easter eggs into their search engine is because Adams was a hugely influential writer on technology. He was one of the first to grasp what the coming information age would mean, and toured the US giving witty, knowledgeable lectures on the subject.

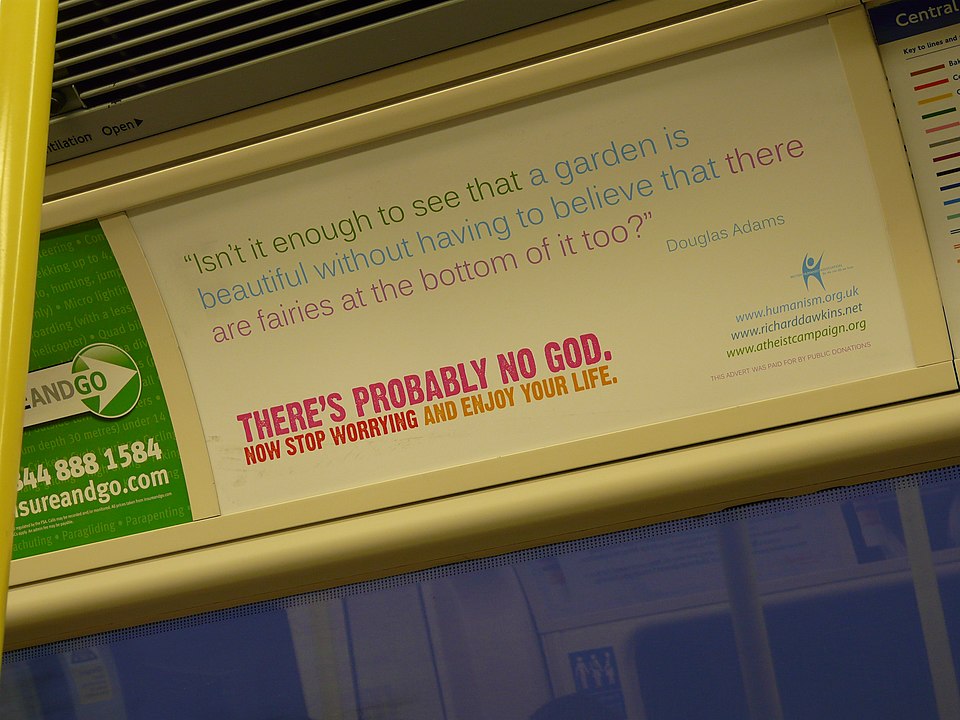

Credit: Loz Pycock from London, UK – Atheist Campaign on Tube Train Uploaded by Trockennasenaffe, CC BY-SA 2.0

But while this won him legions of fans in Silicon Valley, writing was still his bread and butter.

And Adams was starting to find it harder and harder.

When the time came to write the third Hitchhiker’s book, Adams simply cannibalized one of his old, unproduced scripts for Doctor Who. And so it was that Doctor Who and the Krikket Men became Life, the Universe and Everything.

By the time the fourth book in the increasingly inaccurately-named trilogy came out, in 1984, Adams could barely stand to be with his own creation.

“To be honest, I really shouldn’t have written [it],” he later said, “and I felt that when I was writing it. I did the best I could, but it wasn’t, you know, really from the heart.”

But even as his chronic procrastination began to turn into fully-fledged writer’s block, Adams’s luck kept right ongoing. At the start of the decade, he met his future wife, Jane Elizabeth Belson. He also met an absurd number of famous people. Before long, Adams and Belsons’s house in Ilsington was throwing parties where you could bump into anyone from John Cleese, to Stephen Fry, to Richard Dawkins.

Yes, that Richard Dawkins. Adams described himself as a “radical atheist,” and was naturally besties with the scientist.

But perhaps the coolest people Adams befriended were Pink Floyd. There are legends that, halfway through his parties, Adams would hand out guitars, and treat the crowd to an impromptu Pink Floyd gig. But even as Adams’ star rose, he was beginning to discover just how ephemeral this shiny world was. In 1985, Adams was sent alongside zoologist Mark Carwardine to Madagascar to write an article about endangered animals for the Observer.

The two hit it off and, a couple of years later, did a radio series together about endangered species.

It was a show that would change Adams’ life. The show and it’s book Last Chance to See was Adams’ personal wake-up call to the damage humans were doing to their environment. In the aftermath, he would become one of the earliest, loudest voices on conservation and the dangers posed by habitat destruction.

Still, the 1980s ended on a relatively good note. Adams managed to get over his writer’s block long enough to write two Dirk Gently detective stories (one of which, again, cannibalized his old Doctor Who scripts) and, in 1991, finally married Jane Elizabeth Belson.

At the start of the 90s, Adams was in his late thirties, world famous, rich, and married to the woman of his dreams. If this kept up, who knew what the rest of his life would be like?

Unfortunately, we here in the future already know the tragic answer.

Douglas Adams may have not yet been forty…

…but he was already entering the final decade of his life.

So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish

The last ten years of Adams’ life dawned with the writer in a bleak place. After nearly seven years, he’d agreed to write the fifth Hitchhiker’s book, on the understanding that it would be the last.

Even so, his writer’s block crippled him.

There would be nothing, for weeks on end. Nothing but Adams locked away in hotels by his grim-faced editor, staring at the ceiling.

We’ve heard tales that the publisher hired a fleet of writers to sit downstairs, churning out chapters based on Adams’ outline, until Adams was finally roused to work by the thought of all these other writers doing his book wrong.

Mostly Harmless was released in 1992. It was, without a doubt, the bleakest thing Adams ever wrote, with a downer ending that leaves a nasty taste in the mouth. Much later, Adams would claim he’d been seriously depressed while writing it. It really shows. Still, life moves fast and, within a couple of years of the gloomy conclusion of Hitchhiker’s, Adams seemed to be living life to the full again.

For his 42nd birthday in 1994, for example, he was invited onstage by Pink Floyd to play a gig with them. Later that same year, his daughter, Polly Jane Rocket Adams, was born. By the 21st Century, Adams was lecturing in Silicon Valley, developing video games with his production company, and working on turning Hitchhiker’s into a Hollywood movie.

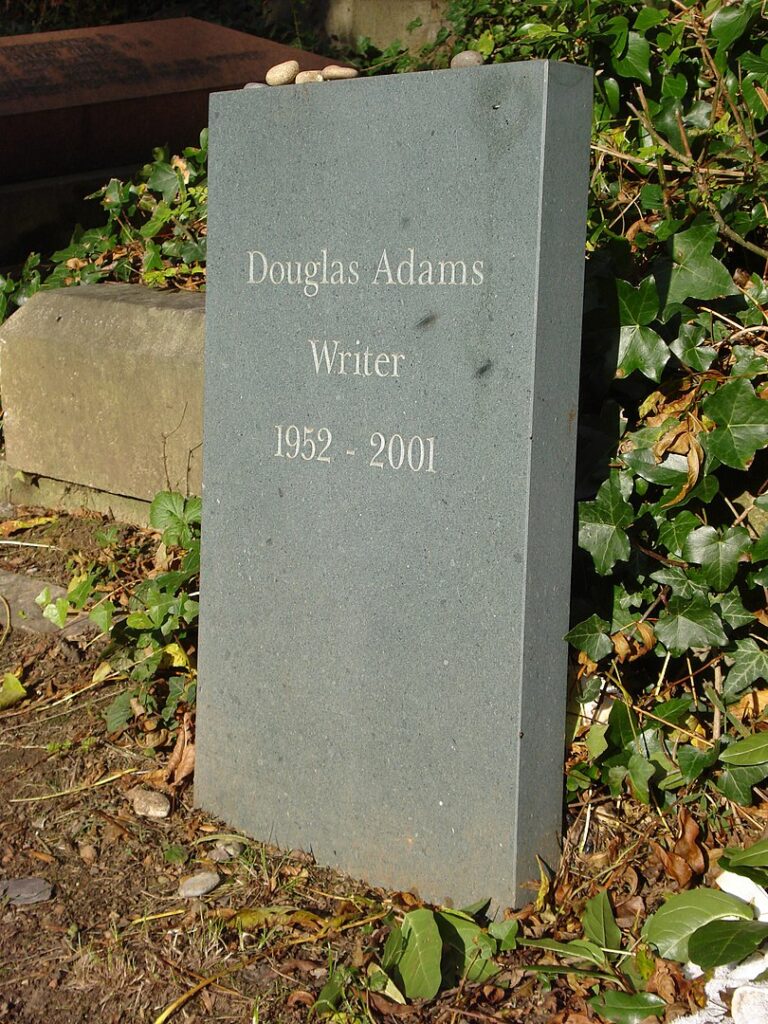

Credit: (aeropagitica) – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

He’d even started writing again, tentatively putting together ten chapters of a third Dirk Gently book that he thought might even become the sixth Hitchhiker’s book. And then it happened. The moment. The moment as shocking to his fandom as the sight of a Vogon Constructor Fleet hanging in the air in much the same way that bricks don’t.

On May 11, 2001, Douglas Adams suffered a massive heart attack at his local gym. At the time he died, he wasn’t even 50. In the wake of Adams’ death, tributes poured in from around the world.

This wasn’t just the regular sadness we feel when someone passes away. This was a keenly felt pain, almost personal – like that felt when John Lennon or David Bowie died. As Stephen Fry later noted, Hitchhiker’s had been sci-fi on a human scale. It resonated with people, made it feel like Adams was talking to them and them alone.

And that may be why his death devastated so many people.

But what should we today make of Douglas Adams? What should we make of the man who wrote a handful of slim, comic volumes before vanishing into the abyss?

Well, it depends on your perspective.

Right now, it’s still too early to tell what Adams’s long-term impact on fiction will be. While he has endless admirers, there’s a sense that his work was maybe too unique, a dead-end for any writer who doesn’t happen to be a comic genius.

On the other hand, Adams’ influence is already everywhere.

We mentioned earlier that Adams was an early adopter – of environmentalism, of computers, of ideas – and part of his charm was his ability to take those ideas and explain them simply, in ways that still impact the ways his readers think.

As Neil Gaiman said in 2015:

“I think perhaps what Douglas was, was a futurologist, or an explainer. One day maybe we’ll realise that the most important job there is, is someone who can explain the world to itself in ways the world can’t forget.”

The continents may grow old and die, the world may be demolished to make way for a hyperspace bypass, but somewhere, out there in the cosmos, some lifeform will always be sat in a restaurant at the end of the universe, reading in wide-eyed wonder as Douglas Adams explains the world to it.

And that lifeform will be smiling.

Sources:

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s entry (paywall – although free to access with a valid UK library card): https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-9000220

The Guardian’s obituary of Adams: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2001/may/15/guardianobituaries.books

A history of Out of the Trees, Adams’ sketch show with Chapman: https://www.vulture.com/2016/07/inside-graham-chapman-and-douglas-adams-lost-sketch-show-out-of-the-trees.html

Adams’s work on Doctor Who: https://www.radiotimes.com/news/tv/2018-01-18/doctor-who-douglas-adams-krikkitmen/

Some background to the Hitchhiker’s radio series: https://h2g2.com/edited_entry/A943184

Destroying the world sketch from Out of the Trees (to be honest, it’s not that great): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mx3-IjHNzTc

Flying Circus episode featuring Douglas Adams’s Patient Abuse sketch (around 08:00): https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x6gf7r1

Some stuff on his Fringe show and (if you scroll up a few pages), a few interesting tidbits on writing for Python: https://books.google.cz/books?id=K-E2cAzsxwUC&pg=PA82&lpg=PA82&dq=the+unpleasantness+at+brodie%27s+close&source=bl&ots=C-pkVvsAli&sig=ACfU3U1t9Ed-CXgdSfpriuAEY1DoMp5ydA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiGnKv6u4DnAhVNx4UKHS3fCRMQ6AEwAHoECAsQAQ#v=onepage&q=the%20unpleasantness%20at%20brodie’s%20close&f=false

Douglas Adams on atheism: https://douglasadams.eu/douglas-adams-and-god-portrait-of-a-radical-atheist/

Last Chance to See: http://www.bbc.co.uk/lastchancetosee/sites/about/last_chance_to_see.shtml

Neil Gaiman on Douglas Adams’ influence: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/04/neil-gaiman-douglas-adams-writer-genius