When it comes to a person’s goals, dreams, and life’s work, it seems like there would be few pursuits more worthy than alleviating world hunger. Surely, bringing food to the starving masses, bringing crops to barren areas of the world, and averting famine, death, and disease is a lofty ambition… isn’t it?

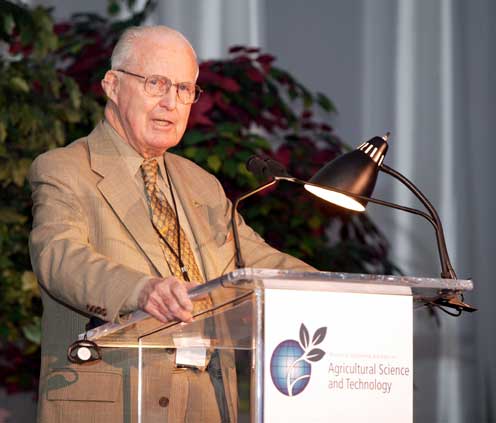

Norman Borlaug truly believed so, and he made it his life’s work to create crops that would relieve food shortages across the globe. Even though his name is hardly a household one, there’s no denying that he shaped the world’s food supply in such a way it’s still being felt today… for better or worse. Borlaug was born in 1914. He lived through World War One, started college during the Great Depression, saw the American Midwest turn into the Dust Bowl, and it was then that he decided he was going to spend the rest of his life introducing high-yield crops to areas who could benefit from them.

And that has turned out to be surprisingly controversial. Murmurs of discontent and cynicism started in the 1980s, and over the following decades, Borlaug’s methods would come under an ever-increasing amount of scrutiny. He remained resolute, though, and the world… well, whether it benefited from his work or was infinitely hurt by it is still up for debate.

Growing up on the farm

While some people find their calling late in life, others have their life’s work shaped by their earliest memories. That was certainly the case with Norman Borlaug; born on March 25, 1914, he grew up on a small farm in Iowa. Those childhood years were shaped by hard work and subsistence farming — that is, farming that yields just enough for the survival of the family, with little or nothing left over for sale or profit. It was an incredibly hard life, made even harder by the fact this was an era before there was help from mechanization and tractors. For much of his youth, in fact, there wasn’t even any electricity.

When he enrolled in school in 1919, it really was a mile and a half each way… even though that sounds like a bit of a cliche. He thrived in school and on the farm, where he spent his hours doing the chores he’d been tasked with since he could walk: collecting eggs, pulling weeds, and feeding the chickens. The chores, of course, got more difficult as he got older, and working on a farm like this, there was no one job he was in charge of. He did everything, from caring for the animals to separating cream from the milk. And, when times were particularly harsh, and during outbreaks of influenza that would kill several family friends, he would carry hot soup to neighbors who had been quarantined in their homes. Living through that sort of hardship undoubtedly gives a young boy a complete appreciation for struggles. In Borlaug’s case, he would become determined to alleviate them for others.

With little time for extracurricular activities, it may have seemed like a given that young Borlaug would grow up to take over the family farm and follow in his father’s footsteps, but one person changed those plans. His 7th grade teacher — who was also his cousin — recommended he be sent to high school, and he was.

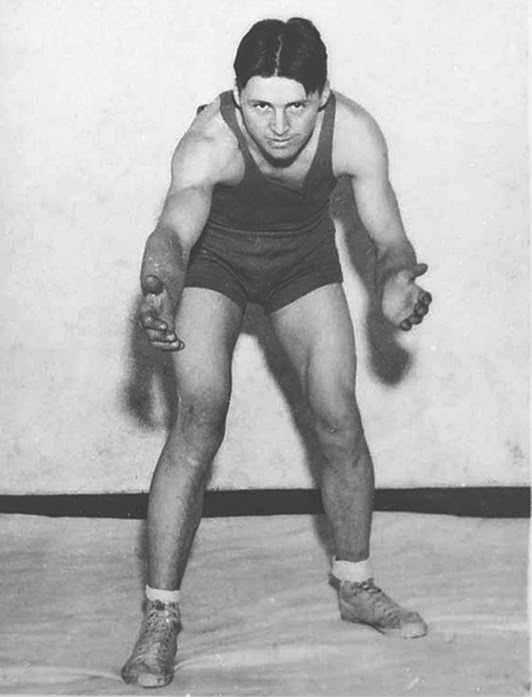

Credit: University of Minnesota Department of Plant Pathology from St. Paul, MN, USA – Wrestling – Norman Borlaug, CC BY 2.0

Cresco High School was 12 miles from the family farm and, of course, there were no buses. Borlaug eventually moved to town, started participating in school sports like wrestling and football, and found himself given one of the greatest gifts a child can receive — a teacher who inspired him.

His name was Harry Schroder, and he was the Vocational Agriculture teacher. Borlaug had been raised with a belief particular to the area and the culture he had been immersed in. As a farmer with a close connection to the land, he had held sacred the richness and fertility of the Iowa soils, and their ability to grow the crops that would nurture and sustain the people who lived there. But when his teacher had the students set up a year-long experiment where they grew crops in both unfertilized soil and soil augmented with things like potassium, nitrogen, and phosphorus, the results provided a valuable lesson.

The augmented soil yielded almost twice the amount of food, and that ended up being a life-changing realization. Sometimes, it takes a while for life-changing events to really make their mark, though, and Borlaug initially flunked the entrance exam into the University of Minnesota. Clearly not one to shy away from hard work, he enrolled in a junior college and ultimately graduated from U of M’s College of Agriculture with a degree in Forestry.

When the world turned to dust…

Borlaug had initially planned on using his degree in forestry, but when the possibility of a job with the Forest Service disappeared, he had to make other plans. He ended up returning to school for a degree in plant pathology, and this was happening at a dark time in America’s history.

And we mean that quite literally. While Borlaug was busy researching a particular variety of fungal disease, he and his co-researchers stumbled across the discovery that outbreaks of the disease were impacted by international harvest cycles; it was as important a moment as his teacher’s lesson about fertilizers had once been. It made it clear that everything was connected, and at the time, something terrifying was forming in the American Midwest: the Dust Bowl.

It was an instance of the perfect storm. Post-war demand had sent the need for staple crops skyrocketing, and families hopeful for a better life moved westward to take advantage of incentives offered by the US government. But that boom was followed by the Great Depression, crop prices crumbled, and those once-optimistic families were suddenly finding themselves unable to make ends meet. They needed more crops to sell, plowed more and more land, and when drought came along with the 1930s, that land no longer had native grasses to protect it from erosion. Valuable topsoil was swept away in massive dust storms called “Black Blizzards”, darkening the skies for days at a time. Dust and dirt from the great plains of the Midwest was dumped along the eastern seaboard and even covered ships in the Atlantic; it got everywhere, it crept into homes and into the lungs of humans and animals alike, sickening those it didn’t kill.

Borlaug watched all this, and was horrified by what he saw going on around him. But he also noticed something: areas being used for experimentation with high-yield crops seemed to be the least impacted by Dust Bowl conditions, and he decided this was the path his life was going to take. High-yield crops seemed to be the answer to two major problems: these crops would be able to feed more people, but they would also help save countless acres of untouched wilderness. If agricultural land was made more productive, Borlaug’s thinking went, there would be no more need to make more of it. Prairies and wetlands would remain untouched, entire ecosystems would be preserved, and native species could continue to thrive.

It was an admirable plan, but in hindsight, there are many who would point out that the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Perfecting some of the oldest crops in the world

Wheat has been a staple crop for somewhere around 10,000 years, and it’s changed quite a bit with the guidance of generations of farmers. By 1944, Borlaug had already spent a few years researching bactericides and fungicides, but with the arrival of World War Two, priorities changed. He partnered with the Rockefeller Foundation and was transferred to the International Center for Maize and Wheat Improvement, or CIMMYT, to use the Spanish acronym. This is where things start to get surprisingly controversial.

Within four years, Borlaug succeeded in improving four strains of wheat. His versions were highly resistant to stem rust, the fungal disease he had been studying earlier in his career, and they also put out higher yields and matured about two weeks faster than previous incarnations the various strains. He also ended up with strains of wheat that possessed “daylight insensitivity,”which essentially means they can be grown almost anywhere in the world, as suddenly it no longer mattered how many hours of daylight they were exposed to.

Borlaug and his team did it by performing thousands upon thousands of crossings, carefully selecting wheat with the traits they were looking for and crossing them to ensure not just healthy plants, but fertile ones as well. It sounds like they were creating an early version of GMO crops, and they sort of were. They weren’t actually mucking about with DNA, though, relying instead on selecting plants based purely on an individual stalk’s, say, strength or yield. It’s worth noting, though, that journals like Nature do consider him one of the early pioneers of the movement, and his family has spoken out about the damage done by the anti-GMO sentiment.

The technology Borlaug and his team worked with was nothing along the lines of what we have today, but by 1954, they had their “miracle seeds.” They were the opposite of what most people might expect, envisioning wide, sprawling fields of tall, slender stalks of wheat. Borlaug’s miracle wheat was based around dwarf wheat, which is brilliant for a few reasons. The shorter the wheat stalk is, the less energy and fewer nutrients go into growing an inedible stalk that just goes to waste. The short stalks are stouter, which means they won’t bend under the weight of their kernels, and there’s less competition for sunlight.

As with most things that sound too good to be true, there was a catch. These high-yield dwarf wheat seeds required more water than standard wheat, as well as needing a ton of fertilizer to reach their full potential. Borlaug campaigned heavily for the use of organic fertilizers with his crops, but getting that much organic fertilizer would mean raising more livestock, which would consume the crops that were being grown… it was a cycle with no easy, straightforward answer… aside from the widespread use of inorganic fertilizers.

Regardless of long-term complications, Borlaug’s new strain of wheat was a massive success almost immediately. By 1956, Mexico doubled their wheat production and no longer needed to rely on imports. That only continued to increase — by 1963, their production was six times what it had been in 1944.

There was no doubt the varieties of wheat Borlaug had carefully cultivated had the potential to change the world, and he became a champion for the idea of spreading these high-yield crops into poverty- and famine-stricken areas that were in dire need of a new and reliable food source. In 1963, Borlaug took his program to Pakistan and India, where he promptly failed to convince them to adopt his wheat as a staple crop.

But conditions there were growing more dire by the day. Food shortages were widespread, and for many, famine and starvation were all too real. By the time Borlaug was able to arrange for a 35-truck convoy to take seeds to LA then load them on a ship bound for India, war had broken out — one more obstacle to overcome. When they received the first shipment and planted their first fields, they did so while working a stone’s throw from artillery fire… and that had to be terrifying. Delays meant the crop didn’t get planted in time but even so, crop yields rose, mass starvation was averted, and by the mid-1970s, both India and Pakistan were self-sufficient when it came to their wheat production.

Borlaug was credited with saving hundreds of millions of lives and averting a major famine. At the same time, his high-yield crops spread even farther, introduced to countries like Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Lebanon, and Egypt. Even as Borlaug’s wheat strains started to grow and bellies were being filled, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

It was 1970, and Borlaug’s world had come full circle. While his roots were firmly planted in America’s Heartland, his parents had hailed from Norway — a country they had left due to extreme food shortages. Borlaug had set out to solve that problem, and it seemed as though he had.

A farmer, a former president, and a war criminal walk into a bar…

By the 1980s, Borlaug had expanded his program to bring not just high-yield crops to Africa, but crop science education, as well. He shouldered a huge burden: removing malnutrition and poverty from towns and villages across Africa. Here, he was most successful with the development of a high-nutrition strain of corn, called Quality Protein Maize.

But much to Borlaug’s outrage, he suddenly found himself fighting an uphill battle in the 1980s. Lobbyists were suddenly attacking his largest supporters, including the Ford Foundation and the World Bank. Because his high-yield crops relied heavily on inorganic fertilizers, environmental lobbyists started putting on the pressure. The green parties of various European countries started leaning on their governments, too, appealing for an end to the export of fertilizer into Africa. For the most part, governments listened.

For Borlaug, it was clearly a case of the elite deciding what was best for the poor and the starving. He didn’t mince words, saying of the lobbyists, “They’ve never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they’d be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.”

Fortunately for Borlaug, it wasn’t a battle he needed to fight alone. By 1984, he had fallen in with two unlikely allies. The first was former American President Jimmy Carter. Carter — who was also from an agricultural background — had also taken up the cause of improving the state of the agricultural industry in Africa. The second was a little less expected: it was Ryoichi Sasakawa.

Sasakawa was… well, his 1995 obituary referred to him as the “last of Japan’s A-class war criminals,” “a monster of egotism, greed, ruthless ambition, political deviousness, and with a love of the limelight,” and a “loveable rascal” … and that’s all in the first paragraph. A self-educated and larger-than-life figure who was so thrilled to be instructed to report to prison as a World War Two, A-class war criminal that he showed up with a brass band to announce his arrival, he was definitely… colorful?

His tale is one of illicit love affairs and illegitimate children, of treasure-hunting and a gambling empire, and — in 1982 — a collapse while attending a geisha party. Then 84 years old, it was another four years before he had an apparent change in heart. Where he had once founded Japan’s Ultra-Nationalist People’s Party (and fashioned himself in the style of his heroes, Hitler and Mussolini), he now founded the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. Through his foundation, he funneled an insane amount of money into education and various other benevolent charities… sure, it was in an attempt to snag a Nobel Prize, but… it’s the thought that counts?

It would be impossible to imagine a figure more different than Borlaug, the quintessential Midwestern farmer, humanitarian, and mastermind of all things agricultural. But somehow — proving that sometimes, truth really is stranger than fiction — they formed a partnership. Sasakawa had been reportedly shocked that Borlaug — who held the Nobel Prize he so desired for himself — had been denied funding for his philanthropic work in Africa. So Sasakawa gave him a call.

Borlaug hesitated at first, and not because of the rather shady nature of his newfound benefactor. He was 71 by this time, and Sasakawa convinced him to kick off his projects by simply saying, “I’m fifteen years older than you, so I guess we should have started yesterday.”

Sasakawa and Borlaug — with Jimmy Carter along to round out this truly strange trio — headed to Africa. They selected the locations for their projects, which included Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Tanzania, and it wasn’t long before the production of staple crops like wheat, corn, and sorghum skyrocketed.

Savior of millions, or destroyer of worlds?

Not everyone who studied Borlaug’s work was thrilled with the outcome. While lobbyists had stymied his work in Africa, they weren’t the only ones warning of the dangers of high-yield crops. Some — like the ecologist Vandana Shiva, condemned the crops as contributing to a reduction in soil fertility and genetic diversity, also claiming the crops’ reliance on fertilizers had kicked off a long-term cycle of rural poverty and debt. The farming practices he promoted were undeniably high-maintenance, and critics began to question whether or not it was sustainable.

Critics also condemned Borlaug for another reason, and this… this is going to get dark. While he shouldered the heavy burden of eliminating world hunger, there were those that suggested that people were hungry for a reason, and that widespread famine was the Earth’s own sort of population control. The more food there is, the thought process goes, the more mouths there will be to feed, a state some touted as problematic.

We did say it was going to get dark.

Over the course of his career, Borlaug had an argument for all of the problems naysayers had with his work, and he was a life-long proponent of population control. Interestingly, his high-yield crops and elimination of hunger went hand-in-hand with that. When he was growing up — on a subsistence farm, during the hardships of wartime and economic depression — families tended to have handfuls of children. They were needed to work the farm, after all, just as he and his siblings did. And, it was sort of assumed that not all of a family’s children were going to survive. He knew that firsthand, too, burying his baby sister when he was still a boy.

It was an Indian diplomat named Karan Singh who made the comment, “Development is the best contraceptive,” and the statistics support that idea. When food is plentiful — and when high-yield crops are put in place — societies tend to have lower death rates and, in turn, lower birth rates. It both seems counter-intuitive and makes sense at the same time, and it was precisely these types of arguments that Borlaug often found himself embroiled in.

Still, in spite of the naysayers and the critics, Borlaug continued his work. In 2003, he visited Uganda and noticed there was an outbreak of a new type of wheat stem rust disease — the very disease he had started out studying decades before. Thanks to his vigilance, the USDA and the University of Minnesota confirmed the outbreak and started down the path of finding a way to stop it — with the help of Bill and Melinda Gates, and the formation of the Borlaug Global Rust Initiative.

Over the course of his career, he was awarded a shocking number of accolades. In addition to the Nobel Peace Prize, there was also the Congressional Gold Medal, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences… the list goes on and on, and includes more than 50 honorary doctorate degrees from institutions around the world. He didn’t just received awards, he gave them, too. In 1986 — with the help of General Foods — he established the World Food Prize, an endowment of $250,000 to those who have gone above and beyond to eliminate world hunger and poverty.

According to his daughter, he truly did work up until the day he died. That was September 12, 2009; he passed away at his Dallas, Texas home after a battle with lymphoma. His daughter later said that he had always considered his work unfinished, and his last words were ones of concern — he was worried about the farmers in Africa who were still struggling.

Over the course of his life, Borlaug was credited with saving somewhere around a billion lives with his Green Revolution, and even said himself, “There are no miracles in agricultural production,” even though the families he saved with his high-yield crops may have a different opinion. But long-term, things are less clear.

When food riots broke out among the starving in 2008, Borlaug’s wheat strains covered about 80 million hectares of the planet’s surface. The problem was the same — people were multiplying too fast for the food supply. Those touched by the Green Revolution in Asia were feeling something else — farms were consolidated into the hands of the rich. The toll of these high-maintenance crops was starting to show; dams were built, waters were drying up, and those that were still running contained high amounts of the same fertilizers required for getting those high yields.

His efforts in Africa faced roadblocks that have proved all but insurmountable. A lack of infrastructure made getting the massive amount of fertilizer to the farmlands difficult, and irrigation was another challenge. But back in 1970, when he accepted his Nobel Prize, Borlaug seemed to know that these challenges were not going to go away easily. He said:

“It is true that the tide of the battle against hunger has changed for the better… but ebb tide could soon set in, if we become complacent. […] civilization as it is known today could not have evolved, nor can it survive, without an adequate food supply. The first essential component of social justice is adequate food for all mankind.”